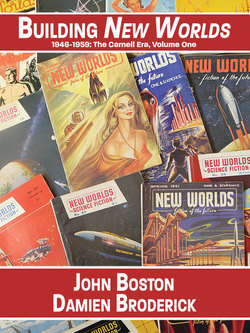

Читать книгу Building New Worlds, 1946-1959 - Damien Broderick - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

by Damien Broderick

John Boston is an occasional amateur science fiction critic of long standing, and attorney (Director of the Prisoners’ Rights Project of the New York City Legal Aid Society and co-author of the Prisoners’ Self-Help Litigation Manual).1 Perhaps it’s not surprising, then, as he once remarked wryly, that he’s fond of escape literature.

Several years ago, Boston read through every issue of the classic British science fiction magazine New Worlds—sometimes with grim disbelief, sometimes with unexpected pleasure, often with gusts of laughter, always with intent interest. That magazine is best remembered today as the fountainhead of the New Wave of audacious experimental SF in the second half of the 1960s, and beyond, under the great helmsman, Michael Moorcock, and his madcap transgressive associates. But these 141 pioneering issues, from 1946 to 1964, were edited by the magazine’s founder, Edward John (Ted, or John) Carnell (1912-72). Not to be confused with the prominent Baptist theologian and apologist of the same name, Ted Carnell was a pillar of the old-style UK SF establishment, but gamely supportive of innovators—most famously, of the brilliant J. G. Ballard, whose first work he nurtured.

Indeed, as Moorcock remarked many decades later: “Ted Carnell always wore sharp suits and I’ll swear he had a camel hair overcoat. He looked like a successful dandified bookie. [He] stood out from the general run of fashion-challenged fans who adopted the universal sports coat and flannels.” It was a distinction in style that catches the difference between the generations of old New Worlds and new. Moorcock added: “Ted would never be caught dead with patches on the elbows of a sports coat. Charles Platt tells me how disgusted he was when he first met me in Carnell’s office and saw that I was wearing Cuban-heeled boots and tight trousers, etc. He didn’t feel anyone could be taken seriously who cared that much for fashion. I didn’t, of course. I was just wearing what my peers were wearing around Ladbroke Grove in those days.” 2

John Boston, for his own amusement, found himself writing an extensive commentary on those early, foundational years of New Worlds and companion magazine Science Fantasy and Science Fiction Adventures. He posted his ongoing analysis in a long semi-critical series to a closed listserv devoted to enthusiasts of pulp and subsequent popular magazines. The present study, published in three parts (two of them largely focused on New Worlds) due to the length of its exacting but entertaining coverage of these 15 years of publication, is an edited and reorganized version of those electronic posts. This volume covers the early years of New Worlds, from its precarious birth to the point at which it had become solidly established as the UK’s leading SF magazine.

I found Boston’s issue-by-issue forensic probing of this history enthralling and amusing, and read it sometimes with shudders and grimaces breaking through, and often with a delighted grin at a neatly turned bon mot. Don’t expect a dry, modishly theorized academic analysis, nor a rah-rah handclapping celebration of the “Good Old Days.” This is a candid and astute reader’s response to a magazine that, by today’s standards, was often not very good—but one that was immensely important in its time, and improved, like the Little Engine (or maybe Starship) That Could. The story of how New Worlds got better, achieving and consolidating its position, is an essential piece of the history of the genres of the fantastic in the UK, and indeed the world.

I had the good fortune, as an SF theorist and writer, to read these chapters as they arrived via email. Greatly entertained, often flushed by nostalgia (for this was the literature of my remembered youth), I insisted to John Boston that his work deserved to be read by as many interested people as possible. He was busy on important legal work in defense of those lost in an overburdened US criminal justice (or “justice”) system, and had no time for such laborious scutwork. I rapped on his internet door from time to time, insisting that it would be a shame—a crime, even—not to allow this material to be read by the world at large.

At last he buckled, passed me his large files covering all the issues of Carnell’s New Worlds and the short-lived Science Fiction Adventures (some quarter million words), plus another large book’s worth of equivalent reading into Science Fantasy (my favorite as an adolescent, in colonial Australia). All three volumes of reading and commentary really comprise one large book of some 350,000 words—and I can only recommend that after you enjoy this first volume, you’ll hasten to read the other two as well.

* * * *

The prehistory of New Worlds is well recorded, especially by SF fan historian Rob Hansen.3 “Scientific romances” had a long if patchy history prior to the 20th century, and the names Jules Verne and H.G. Wells are justly famous as the 19th century “fathers of SF”—with Mary Shelley, author of Frankenstein, arguably the mother. But commercial mass market science fiction (or “scientifiction”) was launched in the USA by Luxembourgian immigrant Hugo Gernsback, an atrocious writer with a zest for wacky ideas (television, for example, and space travel) and a habit of cheating his writers. In August 1926 he brought out Amazing Stories, the first commercial genre magazine specializing in SF. Within a year, a teenaged English schoolboy, Walter Gillings (1912-79), found a copy and became obsessed with the idea of publishing a British SF magazine and forming a support group of other enthusiasts. Other proto-fans found each other and formed local groups. Liverpool rocket enthusiasts formed the British Interplanetary Society (BIS) in 1933, which quickly gathered in a number of young men who, a decade or two later, would embody the core of British SF: Arthur C. Clarke (then 16), Eric Frank Russell (an elder statesman at 28), Ted Carnell (21), Bill Temple (19), David McIlwain (then just 12, destined to publish SF as “Charles Eric Maine”) and others.

Hansen notes the brief flickering of a weekly boys’ paper, Scoops, that ran from February to June of 1934, guttering out before it could develop into anything more adult. Meanwhile, amateur magazines devoted to science fiction and the doings of its fans—and hence dubbed “fanzines”—appeared in the UK as well as the USA and elsewhere; the most consequential was Novae Terrae. Twenty-nine issues were published by Maurice Hanson and Dennis Jacques between March 1936 and January 1939, then Novae Terrae was handed over to the new editor, Ted Carnell, in his late twenties—more or less in time for Hitler’s war to put an end to such frivolities. Carnell was able to publish four issues of the fanzine under his de-Latinized title, New Worlds. With Britain’s declaration of war on Nazi Germany in September, 1939, the BIS and the Science Fiction Association perforce disbanded “for the duration.”

In 1939, Carnell had met with a journalist, Bill Passingham,4 who’d interested a company called The World Says in his plans to publish science fiction. A scheme to convert New Worlds to a professional magazine went as far as acquiring rights to a Robert Heinlein story (“Lost Legacy,” which later appeared in Super Science Stories as “Lost Legion” and under the correct title in Heinlein’s collection, Assignment In Eternity). All these plans fell apart when The World Says went into liquidation.5

The Blitz began in late 1940, with apparently endless swarms of German bombers striking at Britain’s less powerful forces. Carnell and Temple, among other SF fans, were called up, Carnell joining the Royal Artillery in September. The technically skilled among the fans, such as Arthur C. Clarke, went off to Signals or in Clarke’s case into the development and testing of early radar aircraft landing systems. It was a bitter irony that the rockets to which they were all devoted, the utopian vehicle for space exploration, came crashing down bloodily on London, first as primitive cruise missiles (V1s) and then, toward the end of the war, as von Braun’s V2s. Later, these would form the basis of successful US and Soviet efforts to build satellites and crewed spacecraft, yea, even unto the fabled first landing on the Moon. For all that, the murderous V2 wasn’t the shape of things to come that SF fans had hoped to see.

* * * *

Science fiction and its devotees were often ridiculed in those days for “that crazy Buck Rogers stuff”—at least, until the rockets fell, and then a few years later when two nuclear bombs evaporated a pair of Japanese cities. But for all the appeal that futuristic and often jejune adventure stories undeniably had for kids (mostly young males), the British writers who went through the furnace of World War Two were not innocent dreamers, not the “anoraks” who are still mocked for their love of gaudy fantastika. Rob Hansen quotes a remarkable and chilling letter written in Italy in 1944 by British SF writer and WWII veteran William Temple (using the abbreviation “stf” from Gernsback’s “scientifiction”), that makes this utterly clear:

When we come up against the “hard realities” of life, our stf nonsense is supposed to be knocked out of us.... Actually, there’s nothing in that hard, real, outer world that is not enhanced and roselit and made wondrous by the cosmic view....

In the Army, I have grown intimate with all types of people, from miners, labourers, slaughterhouse men to professional soldiers, musicians, college men and boxers. I have watched these men in peril of death, and I have seen them die, not always pleasantly or easily. I have been near enough to death myself more times than I can remember. I have known life at its greatest discomfort in waterlogged foxholes, for many months at Anzio, soaked in the unceasing rain with no hope of drying, hungry, freezing and constantly shelled, machine-gunned, bombed and mortared. In these conditions I have striven to write books and lost them. And rewritten them painfully and lost them again. I have known utter loneliness, and also, the heart-warming comfort of a gathering of my friends. I know what love, marriage, and parenthood are like, and what it is like to be separated from these things year after year, and what it is like to lose a son....

All this sounds a bit melodramatic. I only want to prove that stf is not just a bolthole for people escaping from life. I have lived a fair amount and stf has lost none of its essential meaning through that experience. To me the imagination is somewhere nearer the heart of things than “reality.”6

* * * *

During and immediately after the immense disruption of the war, New Worlds was shelved until demobbed Carnell was introduced to Stephen Daniel Frances, head of Pendulum Publications Ltd, a believer in science fiction, and initiating writer of a series of violent, racy, fake-American thrillers featuring tough Chicago reporter Hank Janson and published under that pseudonym.7 New Worlds as a true SF magazine made its professional debut in 1946 as a more or less pulp-sized magazine from Pendulum, and a rather unprepossessing one, with appalling cover art. This book, and its companion volume, tell the story of Carnell’s magazine from its first timid steps (two issues in 1946, one in 1947, a gap of a year and a half to another two issues in 1949, three in 1950) and then a steady progression: quarterly in 1951, bimonthly in 1952, and monthly from 1955.

New Worlds would maintain its monthly schedule for the rest of Carnell’s tenure, with one exception resulting from an industry-wide labor dispute. Over the first two years with monthly issues, 1956-57, New Worlds serialized five novels by regular contributors to the magazine, each of which attained book publication (mostly as Ace Doubles, the ground floor of American SF publishing). While none was outstanding, together they illustrated the fact that Carnell had by then developed a group of writers who could provide sufficient copy—meeting a basic professional standard at all lengths—to sustain a monthly magazine without continued resort to heavy use of US reprints. Conversely, it meant that he was now providing a regular visible, and readable, presence for new readers and a reliable enough market to be attractive to potential new writers. New Worlds’ serials continued to supply both US and UK publishers with novel-length works for the rest of Carnell’s editorship, and Carnell interspersed these home-grown works with judiciously selected reprints from American sources that had not found UK magazine publication. These included Philip K. Dick’s Time out of Joint and Theodore Sturgeon’s controversial Venus Plus X, but also works by well-known UK writers such as Eric Frank Russell, Charles Eric Maine, and Brian Aldiss that he in effect repatriated for the home audience. During the early 1960s (covered in the companion volume to this one), New Worlds continued to nurture the spectacular careers of Brian Aldiss and J. G. Ballard and the solidly impressive career of James White, as well as the more prosaic and in some cases neglected ones of Colin Kapp, Philip E. High, Lee Harding, Robert Presslie, Arthur Sellings, Donald Malcolm, and R.W. Mackelworth. John Carnell had made his indelible and enduring mark on the history of British science fiction.

1. See “The Long Road Toward Reform,” http://www.wahmee.com/pln_john_boston.pdf (visited 9/9/11).

2. Moorcock, letter to the editor, Relapse, Spring, 2011, p. 28: http://efanzines.com/Prolapse/Relapse19.pdf (visited 9/9/11).

3. Rob Hansen has commendably made available online a record of this important transition: http://www.fiawol.org.uk/FanStuff/THEN%20Archive/NewWorlds/NewWo.htm and much of the background on SF’s fan groups and emerging professionalism is recorded by Hansen in his general online history starting at http://www.ansible.co.uk/Then/then_1-1.html (both visited 9/8/11) and detailing people and events, often from letters and interviews, from 1927 through to the late 1970s.

4. Passingham was also an SF writer in his own right, having contributed stories with such titles as “Atlantis Returns” and “When London Fell” to the UK magazines Modern Wonder and The Passing Show. Walter Gillings, “The Way of the Prophet,” Vision of Tomorrow, May 1970, p. 63.

5. Carnell’s own, more detailed account of these events appears in John Carnell, “The Magazine That Nearly Was,” Vision of Tomorrow, June 1970, pp. 48-49.

6. This was first published in the Los Angeles SF Society fanzine Voice of the Imagination (familiarly, VoM) and is cited by Hansen in http://www.ansible.co.uk/Then/then_1-2.html (visited 9/8/11).

7. Carnell’s more detailed account of these events appears in John Carnell, “The Birth of New Worlds,” Vision of Tomorrow, September 1970, pp. 61-63.