Читать книгу Building New Worlds, 1946-1959 - Damien Broderick - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1: BIRTH AND NEAR-DEATH (1946-47)

As chronicled by literary historian Mike Ashley and others, New Worlds made its long-delayed debut in 1946 (after its earlier fanzine incarnation) as a more or less pulp-sized magazine from Pendulum Publications Ltd., 64 pages exclusive of covers, price 2 shillings (2/-), down to 1 shilling and sixpence (1s 6d, or 1/6) for the third issue.8 The issues are numbered (hereafter indicated in bold), but 1 and 2 bear only the year, no month; 3 bears no date at all. The Science Fiction, Fantasy, & Weird Fiction Magazine Index, a comprehensive database compiled by Stephen T. Miller and William G. Contento (hereafter Miller/Contento), identifies the dates as July and October 1946 and October 1947.9

In his editorial in 3, John Carnell says “We apologize most profoundly to all our readers who have been wondering when this issue of New Worlds would appear. Probably no magazine issue has been beset by so many obstacles since it went into production, almost all of them in the technical departments. In the main, we were caught by the power cuts and have only just managed to recover.” Britain had endured its most severe cold weather of the 20th century, and the postwar electricity supplies were overwhelmed.

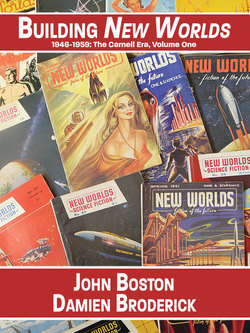

The cover presentations of these early issues are pretty cheesy, resembling the winners of an art contest among fifth-graders. The cover of 3 rises perhaps to junior high school level.10 The first issue’s cover, by Bob Wilkin, an artist employed by Pendulum, portrayed a mushroom cloud bulging above an ambivalent background, corporate-utopian on the left and ruined debris on the right, and a nude, bombed-looking, rather plastic pink man of the future in the foreground. Sales of that first issue were terrible—3000 of 15,000 copies were sold—and Carnell, who had not approved, or even seen, the cover until it was completed, later described its execution as “flat and two dimensional, dull and uninspiring.” Not surprisingly, then, “One point... I was insistent upon—the second issue, already committed to the printer, needed an eye-catching cover painting.” So he designed it himself, combining a spaceship from the cover of a 1937 issue of Astounding Science Fiction and another from a 1938 Amazing Stories. Victor Caesari worked from Carnell’s sketch, and Carnell said: “While not technically perfect it still had good balance and colour and was a striking improvement over No. 1.” The second issue sold out, though not entirely because of the cover—the publisher mounted an “all out drive” on its behalf. But seeing the results, Pendulum proceeded to reprint the cover, substitute 1 for 2, and re-distribute the unsold copies of the first issue, with great success.11

The interior illustrations in 1 and 2 are about as bad as the covers (by Wilkin, perpetrator of the first version cover of 1). Those in 3, by Dennis and by Slack (responsible for that issue’s cover),12 are only a minor improvement.

Like American pulp magazines, the Pendulum New Worlds had a fair amount of advertising not exactly tailored to its content. The back covers and inside front and back covers bear ads for baldness cures; a career guide from the British Institute of Engineering Technology; “Attack Your Rheumatism through PURE Natural Stafford Herbs”; British Glandular Products Ltd. (“Glands Control Your Destiny!” For men, “testrones”; for women, “overones”); Charles Atlas, who will use Dynamic Tension to build you a more manly body; the British Institute of Practical Psychology (“Inferiority Complex eradicated for ever”); and (my favorite)—jockstraps.

This last is headed “Wherever men get together...” and has nice little drawings (much better done than anything illustrating the fiction) of a man getting his petrol tank filled by an attendant, a man reading something off a clipboard to another man wearing an eyeshade and seated at a typewriter, and a man cutting another man’s hair in a barber’s chair. None of these activities ever seemed to me to call for an athletic supporter (though I confess I have never actually cut anyone’s hair—maybe it’s more strenuous than it looks), but the pitch of Fred Hurtley, Ltd., for the Litesome Supporter is quite global: “You can be sure that wherever men get together—there you’ll find ‘Litesome.’ It’s grand to buy something and know you couldn’t have done better. You get that feeling with ‘Litesome’ once you’ve experienced its comfort and protection and the increased stamina and vitality which this essential male underwear gives to every man. Whatever your age or condition, whatever your work or your recreation—‘Litesome’ will help you to feel a different, better man!” There are also interior ads in 2 and 3, some of similar ilk, some for more related items such as Fantasy Review and Outlands.

From the beginning, New Worlds contained non-fiction and tried to connect with its readership. 1 has an editorial, small print placed filler-style at the end of one of the stories, which is mostly blather:

The past is fixed and unalterable. Of that there can be no doubt.... But from here on, the future looms ahead as a bewildering Land of If.... The dazzling heights of achievement and the dark depths of failure can all be found in those miriad [sic] possible “tomorrows.” [Etc.]

Comments are invited, and readers are advised to place an order with their newsdealers for the next issue, due in eight weeks. Interestingly, there is nothing about subscriptions here or anywhere else in the magazine. The word is uttered in the editorial in 2, but no rates are mentioned and there is no subscription information anywhere in 2 or 3, though back issues are for sale.

Issue 2’s editorial has not much more than 1’s that is concrete: thanks for the letters, keep them coming, we’re going to make things better, tell us what you want (and do you want a letter column?), and something brief about atomic bomb tests and public consciousness of SF. 2 also contains a one-page article by L(eslie) J. Johnson, sometime contributor to Walter H. Gillings’ Tales of Wonder and collaborator with Eric Frank Russell, on how science is catching up with SF (more blather though less vague than Carnell’s), along with Forrest J. Ackerman’s report on the Pacificon science fiction convention, held in 1946 after being delayed by World War II, with an attendance of 125 and “a dynamic hour’s speech entitled ‘Tomorrow on the March’” by guest of honor A. E. van Vogt.

Also in 2, “The Literary Line-Up” first appears, readers’ story ratings from the first issue, comparable to the US Astounding Science Fiction magazine’s “Analytical Laboratory” (also Astounding’s “In Times to Come,” since it predicts the next issue’s stories), but without the actual numerical averages that gave John W. Campbell’s “AnLab” its air of spurious precision. “The Literary Line-Up” persisted through the Carnell era and even into Michael Moorcock’s editorship after mid-1964, though he retitled it “Story Ratings.” In 3, the submission of ratings is encouraged by offering five guineas to the reader whose ratings anticipate the aggregate ratings or come the closest (one would think there would always be multiple winners any time more than a dozen or so readers responded). Also in 3, “The Literary Line-Up” notes that the response from readers on a letter column was equivocal, so the question will be left open until a regular publication schedule is established. The editorial in 3 (after the apology for the year’s delay) notes the drop in price, the story rating competition, the death of Maurice G. Hugi and his story in that issue, and touts Walter Gillings’ Fantasy Review.

* * * *

To be frank, most of the fiction in these issues deserves its obscurity. Lead novelette in 1 is “The Mill of the Gods” by the doomed Maurice G. Hugi, in which the world is flooded with cheap and high-quality consumer goods from a mysterious company (a notion that also motivated Clifford D. Simak’s 1953 novel Ring Around the Sun). The boys from Intelligence do a black bag job at one of the company’s sites and find themselves on an alternate Earth, lorded over by refugee Nazis who have subdued the already docile native population for their factories. These refugees plan to return and reassert Germany’s rightful dominance as soon as their economic warfare has reduced Earth to chaos. So they explain, in time-honored pulp fashion, before locking our heroes up, rather than shooting them out of hand like any sensible gang of villains would do to prevent the good guys’ otherwise inevitable escape and triumph. It might have been competitive in Thrilling Wonder Stories a decade previously.

The other novelette, William F. Temple’s “The Three Pylons,” is an only slightly fresher kettle of fish, a piece of schematic moralizing involving the new king of an archaic kingdom whose deceased father has set him a quest: ascend three pylons he has had built, each of which requires a higher technology, and each of which has a message for him on the top. The new king meets these challenges but is such an arrogant and aggressive SOB that he destroys himself.

The rest of the issue comprises no fewer than four short stories by John Russell Fearn13 under his various guises, all ridiculous but somehow inoffensively so. There is a certain archaic charm to his work that makes it less irritating than, say, the earnestly laborious Temple story. Reading Fearn is like reading David H. Keller, maestro of the early Gernsback epoch. He doesn’t pretend to be anything but a moldy fig.

Here’s an example, “Sweet Mystery of Life,” under Fearn’s own name, capturing the tenor of these early issues of New Worlds. Maxted, who lives in a village but has a good Civil Service job in the City, is trying to grow a black rose, supposedly the Grail of horticulturists. His latest cutting withers, but something else appears in its place, looking at first a bit like a toadstool—but it has a face, and microscopic examination shows it’s a human being growing in the potted soil. Maxted tells his servant, “Belling, we’ve stumbled on something infinitely more amazing than a black rose!” Later, he asks Belling if he knows Arrhenius’s theory. “You mean the one about him believing that life came to Earth through indestructible spores surviving the cold of space and then germinating here?” Ah, for the days of old England, when every gentleman had a servant and the servants knew Arrhenius!

The visitor to the conservatory proves to be a woman, or the top half of one, and she’s from Venus. Her name is Cia and her years of sporehood have not impaired her memory or linguistic ability. “We of Venus need a race like yours to free us from bondage,” i.e., from being legless torsos growing out of the soil. Cia has gobs of advanced scientific knowledge ready to recite off the top of her head. Alas, Idiot Jake, whose favorite amusement is tearing up bits of paper and throwing them off the nearby bridge so he can watch them float down the brook, has been eavesdropping and telling tales. When he throws a tree branch through the window, letting in the cold night air (“charged with frost”), Cia freezes. The police arrive, with various snoopy locals, following up a report of a woman being ill-treated. By now Cia resembles a statue and Maxted passes her off as such. The visitors depart. At least Maxted has his copious notes of Cia’s scientific revelations. But wait—they’re gone! Pan to Idiot Jake, tearing up the notebook and throwing the pieces into the brook.

The other Fearn stories include “Solar Assignment,” as by Mark Denholm, in which a spaceshipful of reporters encounters people on Pluto, zombified and operated by aliens, and amorphous and viscous aliens at that. “Knowledge Without Learning” is a psi story guaranteed not to have pleased John W. Campbell, Jr. A telepath absorbs knowledge from others, but it’s zero-sum: what he learns, the sender loses, like the bus driver who suddenly discovered he didn’t know where he was or how to drive. “White Mouse” as by Thornton Ayre is about the first mixed marriage of Earth human and Venus human, and the climate of Earth doesn’t agree with the bride.

A much higher grade of the ridiculous appears in John Beynon’s “The Living Lies,” the lead (though not the cover) story in 2. On Venus, there are four races: the Whites, the Greens, the Reds, and the Blacks. The Whites—Earth colonists—lord it over the others, who exist in a state of mutual dislike and suspicion, to the benefit of the Whites. (The fact that not everybody on Earth is white, or White, is mentioned in passing, but that’s it.) These racial differences prove to be entirely manufactured by the Whites; everybody on Venus was white to begin with. Now, all children are born in hospitals, since the risk of infection on Venus is so large, and the doctors whisk newborns off to a hidden room where they are smeared with a pigmenting jelly and exposed to radiation that makes the pigment permanent. Somehow everyone has forgotten that things used to be different, the doctors keep the secret, and nobody else blows the whistle. Presumably all the mothers are anesthetized when they deliver. An idealistic young woman who first is repelled by the racist set-up and then, when she discovers the real story, tries to expose it, comes to a bad end.

Within its absurd premise, the story (by the author later much better known as John Wyndham, of Triffids fame) does a reasonably good job of pinpointing the interaction of self-interest and racist attitudes, and portraying the reactions of people who are uncomfortable with them—but usually only up to a point. Venus, by the way, is very different from Earth, which by this time is governed by the Great Union. Says one of the sympathetic characters, uncontradicted by anything in the rest of the story:

There was a day on Earth when the people revolted. They refused any longer to be thrown into slaughter of and by people of whom they knew nothing, for the profit of people who exploited them. They rose against it, one, another, and another, to throw out their rulers and rule themselves. And so came the Great Union, Government of the People, by the People, for the People, over the whole Earth. How long will Venus have to wait for that?

This unusually Bolshie rhetoric is quite refreshing, at least as a relief from the militarist, social Darwinist, and eugenicist rhetoric to be found elsewhere in the genre.

The cover story of 2, “Space Ship 13” by Patrick S. Selby, is something else entirely, in the running for the worst story I have ever read in an SF magazine. A sample:

“Oh, no you don’t! Hand that envelope over, brother!”

Chuck spun around. The cabin door had opened silently, and a powerfully built man with a sinister looking scar across his right eyebrow stood holding a deadly radium gun level with Chuck’s heart.

“Get out of here!” tried Chuck experimentally, and got slowly to his feet. Slim, away up at the controls, hadn’t noticed anything wrong, not that he’d be much help. “And put that gun away—any accident here might send the ship to dust!”

“I’ll do the worrying about accidents,” growled the man with the scar. “You worry about doing what I tell you. They don’t call me ‘Kleiner the Killer’ for nothin’. Now, gimme that envelope.” He held out his huge fist, and his dark, evil little eyes glittered. “Come on, now!”

If anything, it gets worse. (“‘You swine, Kleiner! I’ll get you before we’re through!’ The racketeer gave an evil chuckle.”) “The Literary Line-Up” in 3 says Selby will be back in the next issue, but apparently good sense prevailed: he wasn’t, and Miller/Contento lists no other appearances for him in the SF magazines.

Things could only get better from there, though not necessarily by much. John Russell Fearn has two stories in issue 2, both reprinted from American magazines: “Vicious Circle” as by Polton Cross (from Startling, Summer 1946) and “Lunar Concession” as by Thornton Ayre (from Science Fiction, Sept. 1941). “Vicious Circle” is about a man who is running for the Bond Street bus and suddenly finds himself in “a formless grey abyss,” and then on an unfamiliar and rather shiny-looking street. A helpful passer-by clues him in: “It may help you if I explain that you are in London—which was resurfaced with plastic in Nineteen Fifty Eight.” He shortly returns to his present, but keeps popping off to other times. He goes to a doctor, who diagnoses him as a freak of nature. (That’s what he says: “You are a freak of nature!” Now there’s a bedside manner.) Specifically, where everybody else’s time line is straight, his is a circle—an enlarging circle (sounds like a spiral to me), and by story’s end he’s about ready to hit the Big Bang and the heat death of the universe on the next swing of the pendulum.14

“Lunar Concession” lacks even the modest charm of “Vicious Circle.” There’s a deposit of super-high-energy Potentium on the moon, conveniently in a valley with an atmosphere. One of the party exploiting it proves to be an Agent of a Foreign Power who wants the Potentium so he can make bombs and seek world domination, as he tediously explains in standard pulp-cardboard fashion while hero and heroine are tied up (once more: rather than just shooting them, as any sane villain would). The day is saved by Snoop, the hero’s faithful dog, who lays down his life, etc.

These are the last Fearn stories to appear in New Worlds. Shortly after, Fearn’s prolific publication in the SF magazines slowed drastically, presumably because he was busy writing novels for the paperback publishers that were springing up.15 He had one story in Science Fantasy but no more in any of the higher-echelon British SF magazines. The rest were in the likes of his own Vargo Statten’s SF Magazine.

The remaining short stories in 2 are inconsequential. “Foreign Body” by John Brody is about an ancient spaceship discovered in a bed of coal and destroyed by ineptitude. Brody was an early case of the Carnell-only SF writer: seven stories 1946-58, all but one in New Worlds or Science Fantasy. He did have four stories in the UK weird magazines (1946-60) as by “John Body.” “The Micro Man” by Alden Lorraine (Forrest J Ackerman) is an inane story about somebody enlarged from the world inside an atom, but not quite enough—he comes to grief in the protagonist’s typewriter. “Green Spheres” by W. P. Cockcroft, is about an invasion by tentacled extraterrestrial carnivorous plants, ultimately done in by water. The author is a veteran of Wonder Stories, Tales of Wonder, and Scoops (not to mention Yankee Weird Shorts), and it shows in this dated War of the Worlds knock-off.

* * * *

The lead story in New Worlds 3 is “Dragon’s Teeth” by John K. Aiken (misspelled “Aitken” on the cover), a “novel” at 27 pulp pages. Aiken (1913-90) is a moderately interesting Little Known Writer.16 He was the son of poet Conrad Aiken, co-editor of a fanzine consisting mostly of fiction and published in a single copy at the Paint Research Station in Teddington, 1942-44 (Aiken was a “biological chemist,” says Carnell in New Worlds 4), and active in the Cosmos Club until its postwar demise.17 He first appeared in the SF magazines with a Probability Zero item in Astounding in 1943.18 This is his second story; altogether, he had five in New Worlds from 1947 to 1952, and book reviews in the two Gillings issues of Science-Fantasy. (He’s the one who described Nelson Bond as “approximately, the P.G. Wodehouse of science fiction.”) He also appeared in a number of the issues of Gillings’ Fantasy Review.

“Dragon’s Teeth” is the first of what Miller/Contento dub the Anstar series, after a main character, and years later Aiken fixed them up as World Well Lost, published as by John Padget in the UK in 1970 but under his own name in the US a year later. Actually, this is what might be called a “reverse fix-up.” Carnell said later (New Worlds 5, “The Literary Line-Up”): “It has taken us a long time to officially announce that the trilogy of stories by John K. Aiken... is in reality a long novel, and because of our somewhat infrequent appearance we had to split it into three separate parts instead of making a serial of the story.” Carnell adds with his typical cramped expansiveness that “the entire trilogy bids fair to become a minor classic of British science fiction.”

In any case, “Dragon’s Teeth” is a reasonably intelligent if cardboard-populated rendition of the peaceful culture menaced by oppressive militaristic invaders, in this case the proponents of the Galactic New Order (Galnos for short), whose advance guard is neutralized by the pacifistically inclined colonists’ genetically engineered (though not so described) iron-eating lichen and hypnotic flowers. For the full Galno fleet, it takes an “adaptation of [the] mesotron beam” that they use to generate mutations. While the main characters are debating the ethical issues of defending themselves with something so destructive, the designated red-shirt sneaks off, blows the fleet out of the sky, and then kills himself, permitting the rest to have it both ways. There will be more on these stories and the book version later on.

The short fiction in this issue is not necessarily better but is much more readable than its predecessors. “The Terrible Day” by Nick Boddie (Boddy on the contents page) Williams is a work of hard-boiled astronomy (“I could imagine that—Kiesel, squatty and bald, glued to the tail-end of that 100in. telescope while Halley’s Comet looped the loop.”), set of course in Los Angeles. A supernova triggers a near-collapse of civilization at the same time the astronomer protagonist is undergoing a near-collapse of his marriage. There is a happy ending on both counts, and as the story closes he is hugging the dog.

F(rancis) G. Rayer’s “From Beyond the Dawn” is completely but pleasantly archaic, the kind of thing that you’d be pleased but not surprised to find in a 1932 Wonder Stories. Derek Faux has established a SETI-by-dots-and-dashes communication with somebody, but there’s no time lag. What’s going on? Suddenly craft full of invincible robots appear in the rock quarry next door. Resistance appears futile. But Faux’s telegraphy yields a clue as to how to destroy them. Meanwhile, in the far far future, highly evolved humans with bodies so feeble and brains so big that all their wheelchairs have headrests are talking about the mysterious signals they are receiving from somewhere and responding to, and the robots they are about to send out to explore for them, and the new theory that time is a loop.

Maurice G. Hugi, who usually doesn’t get much respect, including from me, is back with “Fantasia Dementia,” which is pretty lively considering that the protagonist is in a coma. It’s in the tradition that stretches from “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge” through Pincher Martin to Iain Banks’ The Bridge and Damon Knight’s Humpty Dumpty: An Oval. A car thief tries to flee the police and winds up going through the windshield and into a concrete pillar. After extensive brain surgery he’s paralyzed in the hospital, except—“Hummmm! Hummmm! Hummmm! ZING!”—he is suddenly in a surreal and revolting fantasy world. Then he’s back in his hospital bed. Then (“ZING!” again) he’s in a sort of quasi-Egyptian dream world where he is ruler, but is magicked by an evil priest and put through the death rites while alive but (here too) paralyzed. He returns to hospital, starts to go again, then dies, and Dr. Schrodinger (honest) says, “My God! That’s it! The silver plate was the cause. Silver is a conductor. It made an electrical bridge over the Fissure of Sylvius! Even the three membranes, Pia Mater, Dura Mater and Arachnoid Membrane could not short-circuit it!” The House Surgeon says, “Well, he’s at rest now, poor devil. He won’t zing again.” Carnell says in his editorial that Hugi has recently died at age 43 and knew he was dying when he wrote this story. If so, he was a serious pessimist—at the end of the story it is hinted that the protagonist has actually zinged off a third time to another fantasy world, from which—having died—he will not be able to escape.

We reach the bottom of the barrel with John Brody’s “The Inexorable Laws,” in which space captain Leroy is chasing down space captain Bronberg, who stole his wife, terminal vengeance in mind. They fetch up on a planet where a gang of vile aliens, never seen but holed up in a pyramid, seize both ships with a powerful magnetic field. Leroy bows to “the ethical laws,” i.e., in the cold cruel cosmos Terrans stick together, abandon revenge, and cooperate in getting Bronberg off the planet. Having nothing more to live for, Leroy blows up his own ship and the alien pyramid. The writing is as crude as the story: “Mankind was such a small facet of the vast universe, such a weak growth amid so many perils, that every man who went beyond the field of Terra must be constantly on his guard.”

In this dubious company the quietly elegant “Inheritance” by Arthur C. Clarke (under the Charles Willis pseudonym, for no apparent reason) is a considerable relief. An experimental rocket pilot is confident he will survive because he has dreamed of the future—except it’s not his future he’s dreaming of. It’s a piece of modest ingenuity, modestly presented, and is the best thing in these three issues.

“Inheritance” prompts a question and an observation. The story subsequently appeared in the September 1948 Astounding—the only previously published story ever to appear in Astounding—and I wonder how and why that happened, and whether it has anything to do with the fact that Clarke, after one more story in the September 1949 issue, did not appear in Astounding again until “Death and the Senator” in 1961. It is also worth noting that Clarke published almost no original fiction in New Worlds after this, the only exceptions being “The Forgotten Enemy” in 5 (1949) and “Who’s There” in 77 (1958), with “Guardian Angel” in 8 (1950) being half an exception, since New Worlds published Clarke’s original version and not the one revised by James Blish that appeared in Famous Fantastic Mysteries.

Clarke’s other fictional appearances in New Worlds were all reprints: “The Sentinel” in 22 (1954), reprinted from Ten Story Fantasy; “?” in 55 (1957), reprinted from Fantasy & Science Fiction (as “Royal Prerogative”); and, believe it or not, “Sunjammer” in 148, into the Moorcock era, reprinted from Boys’ Life. It’s striking that the leading UK SF writer of the 1950s appeared so seldom in the leading UK SF magazine, especially since Clarke for some reason was not appearing in the highest-paying US magazines either. As noted, he was out of Astounding from late 1949 to 1961; he didn’t hit Galaxy until 1958; he had only half a dozen stories in Fantasy & Science Fiction through 1970; instead he tended to show up in Thrilling Wonder, If, Infinity, Satellite, etc.

In summary: the beginning of New Worlds appears inauspicious from this distance—although it surely seemed momentous back in the day, and back at the place.

8. One shilling was 1/20th of a Pound, and 6d or sixpence was half a shilling. In 2012 inflated currency, two shillings in 1946 were worth roughly US $4.50.

9. Bibliographic and historical information not from the magazine itself, and not otherwise attributed, is from The Science Fiction, Fantasy, & Weird Fiction Magazine Index by Stephen T. Miller and William G. Contento and Contento’s Index to Science Fiction Anthologies and Collections (both on CD-ROM from Locus Publications); from Mike Ashley’s article on New Worlds in Science Fiction, Fantasy and Weird Fiction Magazines, edited by Marshall B. Tymn and Ashley (Greenwood Press 1985); from Ashley’s recent histories of the SF magazines, The Time Machines and Transformations (Liverpool University Press, 2000 and 2005); from John Carnell’s brief memoir, “The Birth of New Worlds,” Vision of Tomorrow, September 1970, pp. 61-63; and from Rob Hansen’s web site, available on-line. http://www.fiawol.org.uk/FanStuff/THEN%20Archive/NewWorlds/NewWo.htm (visited 9/8/11). Occasional references to the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction are to the Second Edition by John Clute and Peter Nicholls (St. Martins, 1995), the latest available at time of writing.

Also notable is Philip Harbottle’s Vultures of the Void: The Legacy (Cosmos Books, 2011), published as we were completing our work. This book, very much expanded from an earlier, long out-of-print version, is a survey of UK SF publishing which emphasizes book publishing (especially paperbacks) but also includes useful information on the Nova magazines, some of which we have referred to.

10. See these covers at http://www.sfcovers.net/mainnav.htm. That URL takes you to the main page and you’ll have to navigate from there, but how to do so is self-explanatory. Among this site’s virtues is an artist index. Another handy source—and probably easier to use—is http://www.philsp.com/mags/newworlds.html (both sites visited 9/8/11).

11. Carnell, “The Birth of New Worlds,” p. 62.

12. Slack was a pseudonym for Kenneth Passingham, son of Bill Passingham, who played a key role in the aborted effort to start New Worlds in 1940. Id. at 63.

13. Carnell later recounted: “Fearn responded to my urgent request for material by sending over one quarter of a million words and in all those first few months produced over half a million, all of which had to be read and from which a selection had to be chosen for that first vital issue.” John Carnell, “The Birth of New Worlds,” p. 61.

14. Wait a minute! How did an expanding circle become a swinging pendulum? Isn’t that what the Dean Drive was about? At least it didn’t turn into a seesaw—that had been done, by A. E. van Vogt.

15. In fact, as Philip Harbottle reports, Fearn in 1950 signed a contract with Scion Books to write SF exclusively for that publisher for five years. Vultures of the Void: The Legacy, p. 123.

16. This recurrent phrase reflects the view of members of the listserv on which this material was first aired that Attention Must Be Paid to the obscure and forgotten producers of decades-old magazine fiction, a preoccupation in which I enthusiastically joined.

17. http://www.dcs.gla.ac.uk/SF Archives/Then/then_1 2.html (visited 9/8/11).

18. “Camouflage,” Astounding Science Fiction, April 1943. The Probability Zero items were essentially tall tales, brief vignettes that stretched credulity and often amounted to parodies of SF method and logic, some written by Astounding’s regular contributors, others by readers and fans who had few or no other credits in the field, or only obtained them later, like Ray Bradbury. Even New Worlds editor Ted Carnell published one, “Time Marches On,” in the August 1942 issue of Astounding.