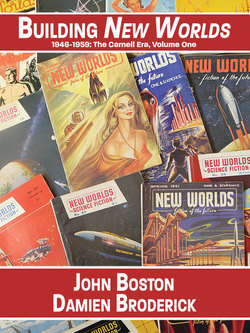

Читать книгу Building New Worlds, 1946-1959 - Damien Broderick - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2: RESURRECTION (1949-50)

Sunk by the bankruptcy of Pendulum Publications19 after issue 3 in October 1947, New Worlds was famously resurrected when attendees of the White Horse Tavern gatherings of SF enthusiasts decided to form their own company to publish it. Nova Publications Ltd. was formed, shares were offered, almost 50 people put up £5 each, and Nova was in business, led by unpaid working directors John B. Harris (John Wyndham), Ken Chapman, Frank Cooper, Walter Gillings, Eric Williams, and Carnell.20

The first Nova Publications New Worlds, issue 4, appeared in April 1949, followed by 5 in September, though only the year actually appears on the magazine. The next issue bravely announced itself as Spring 1950, and was followed by Summer and Winter; what happened to Fall is not explained either in the magazine or by Tymn/Ashley. In 1951 things firmed up and the magazine managed four quarterly issues, then went bimonthly in January 1952 and stayed that way until early 1953, when things got flaky again. Carnell is listed as editor and there is no other editorial staff listed. The magazine is published by Nova Publications, Ltd., 25 Stoke Newington Road, London N.16, and throughout the period is printed by G.F. Tompkin, Ltd., Grove Green Road, London, E.11.

These five 1949-50 New Worlds represent a sharp improvement in presentation—that is, the amateurs of Nova put out a better-looking magazine than the professionals at Pendulum. The magazine has gone from more or less pulp size to a large digest size, 5½ x 8½ inches, at first 88 pages plus covers, then 96 pages plus covers starting with 5. The paper is a reasonably thick stock (getting thinner with 8), a little coarser than typical book paper, but it holds up well. There’s less browning in my copies than in most SF magazines of similar age. The price stays at “one & sixpence.”

The covers are drastically improved. The cover logo is now simple and readable. The subtitle “fiction of the future” remains. With 6, the logo is enclosed in a rectangular box, interrupted on the bottom by the subtitle. The cover of 4, by Dennis, is a bit crude, but it makes a virtue of its crudity, since the picture is purposefully stark and stylized and effective as a result.21 5 is a further improvement, being the first cover by Clothier, whose often busy and always colorful and eye-catching work dominated for the next couple of years. He knew how to be gaudy but not cheesy—not an easy line to walk. (Admittedly some of these covers have become kitsch retroactively simply because their Art-Deco slant has fallen so far out of fashion.)

Clothier, like US favorite Emsh (Ed Emshwiller) in later years, specializes in incorporating his signature into the picture, but even more visibly: 6 includes a map of Venus produced by Clothier Projection; 7 has a vehicle of Clothier Contractors; in 8, the futuristic Clothier Hotel is in the lower right corner. The first Clothier cover is also the first since 1 without a story title over it, which remained the practice for several years. All five of these covers depict spaceships or equally portentous machinery (it’s hard to tell about a couple of them), with human figures at best in a supporting role. There is no statement that the covers illustrate any of the stories, but at least some of them do. The cover of 5, illustrating a spaceship taking off from underwater, is taken from Sydney J. Bounds’ “Too Efficient.” The navigational motif of 6 appears connected with A. Bertram Chandler’s “Coefficient X.” The cover of 8, portraying a giant vessel that looks a little bit like a giant sausage penetrated horizontally by a neon halo and vertically by a body piercing stud, hovering over a futuristic city, seems to illustrate Arthur C. Clarke’s “Guardian Angel.”

Interior illustrations, generally adequate but undistinguished, are by Dennis and White in 4, Clothier and Turner in 5 and 6, Clothier and Hunter in 7 and 8. Carnell says in the editorial in 5 that Clothier is new to SF but Turner is a veteran of 1938-39, and indeed a 1939 issue of Fantasy features illustrations by an H.E. Turner. The strength of Clothier’s covers has a lot to do, both directly and indirectly, with his bold use of color, but his black and white work is fairly nondescript. However, this may be due to limitations in reproduction technology. Comparing these issues with a contemporaneous Astounding (April 1949, illustrations by Cartier, Quackenbush, and Orban), it seems to my amateur’s eye that New Worlds’s printing—not just its artists—is less capable of reproducing fine detail.

Each issue has an editorial and “The Literary Line-Up,” and starting in 5 each has either a book or a film review, one item reviewed per issue. The books covered are William F. Temple’s Four-Sided Triangle (5), Arthur C. Clarke’s Interplanetary Flight (7), and Ley and Bonestell’s The Conquest of Space (8). All the reviews are unsigned except the last, signed “J.C.” The film review is of a documentary called The Wonder Jet, notable for its scene—memorialized here in a still photo—of a man wearing an old-style leather flying helmet with earflaps, rapt in perusal of New Worlds 3. This is signed “W.F.T.,” clearly William F. Temple. The only other non-fiction in these issues is Clarke’s “The Shape of Ships to Come” (4), about what spaceships are likely to look like (maybe like dumbbells with one end larger than the other; spin ’em for gravity and they’ll look like hydrogen atoms). The practice of publishing an article in most issues did not get established until 1951.

Since New Worlds is now its own entity and not the product of a pulp chain, the advertising more or less fits the content and no more jockstraps or gland tonics are on offer. All issues but 4 have ads on back and inside front and back covers (4 has the Table of Contents on the inside front); interior ad pages go from none in 4 to one in 5 to two in 6 and back down to one in 8. Almost all the ads are for books and magazines, mostly SF, though there are exceptions, such as the ad on the inside front cover of 8 for Rider, which sells occult books including Psychic Pitfalls: “An A.B.C. of speaking with the dead, showing us how to avoid mistakes and disillusionments.” Their ad in 7 offers Reincarnation For Everyman by the same author, Shaw Desmond. In several of the issues, Loyal Novelty Supplies, purveyors of Magical Novelties, takes a half-page, complete with cartoon rabbit doing card tricks.

The editorials, formerly crammed in filler-style in small type, are now allocated a full page or two. The two-pager in 4 is titled “Confidence.” Carnell says that the magazine’s existence “calls for a certain amount of justifiable pride,” noting that the previous publisher had ceased business. He says that he first planned the magazine in 1940, now he’s got a team of experts working with him (though as noted none of them are credited), and here’s his manifesto: “I have been certain for a long time that there is a place for British magazine science fiction in this country without the readers having to rely entirely upon the medium of American counterparts (couched, in the main, in a style designed to suit an American reading public and not a British one).”

After noting the history of false starts in British magazine SF, the editorial concludes: “The one vital factor which stands supreme is that this type of literature has been asked for by readers for years, and despite the failures by the wayside, I have every confidence that a good quality magazine such as I hope New Worlds to be, will fill the vital need from an English standpoint.” And there’s a variation or even counterpoint, in “The Literary Line-Up”: “Although we warn you that we shall from time to time experiment with different types of stories, ever pursuing a policy of publishing the best British science fiction available.”

Oddly, Carnell doesn’t say exactly what constitutes this “English standpoint” he’s talking about, nor, by contrast, “a style designed to suit an American reading public and not a British one.” It is noteworthy that there appear to be no US writers in these issues, and only one—Forrest J. Ackerman with his inane vignette and convention report in 2—in the earlier ones. There are a number of reprints from US magazines, but almost no original fiction by US authors, in the magazine’s first decade. There is an Arthur J. Burks story in 10 in 1951; “The Literary Line-Up” in 10 reports that one Hjalmar Boyesen, to appear in the next issue, is an American living in London; and then the next one appears to be Robert Silverberg’s “Critical Threshold” in 66, December 1957. In the magazine’s first years, it seems either that US writers were not even using New Worlds as a salvage market, or Carnell was not allowing them to. The same is not true of Science Fantasy. By the end of 1956, the magazine under Carnell had published five stories, in many fewer issues than New Worlds had published at the time, by the (then) relatively marginal US writers E.E. Evans, Les Cole, Charles E. Fritch, Helen Urban, and Harlan Ellison.

On a more mundane level, Carnell says, “The first thing we did was to change the size of the magazine, feeling that it would be far more popular in the handy pocket size than in the larger more cumbersome one.” Here is a subtle piece of cultural history, evoking the bygone era when everybody (men, that is) not engaged in manual labor wore jackets as a daily routine—this large digest magazine wouldn’t fit anybody’s pants pocket.

The editorial in 5, titled “Progress,” says nothing much, but does note that subscriptions are now available. The issue 6 editorial, “No Comparison...,” takes up the transAtlantic anxiety of influence, or of hegemony, again:

It is understandable that New Worlds should be compared with American science-fiction magazines—they have been almost the sole source of reading pleasure to many people in this country for many years. But that New Worlds should be following in American footsteps I disagree most emphatically. Neither is it our aim to imitate any one American publication.

For twenty years now, experts in the fantasy field in this country have been trying to get a truly British science-fiction publication going successfully—it looks as though New Worlds is going to more than fulfill those expectations and ambitions—and already some of the traditions of American publications are beginning to be radically changed to suit our own reading taste.

British authors will almost always produce stories written differently (in style and presentation), from American writers, around plots approached from a different mental angle, a direct result of different environments, customs and conditions, existing in the two countries. It’s hard work for them to write an American story—writing in an English vein comes more naturally!

Therefore I foresee that the gulf between New Worlds and American contemporaries will widen rather than draw closer....

Once more, Carnell says nothing about what this “truly British” approach is. Many issues later, in 29, visiting US writer Alfred Bester does just that, rather well, in the letter column “Postmortem,” to which we shall return.

The editorial in 7, “Good Companions,” announces the launch of Science Fantasy and anticipates the “friendly rivalry” that the two editors (Carnell and Walter Gillings) will develop. That lasted only two issues, and Carnell was editing both magazines starting with Science Fantasy 3. “Conventionally Speaking” in 8 announces the International Science Fiction Convention, to be held in the Bull and Mouth Hotel (not a typo) in May 1951, later shifted to the Royal Hotel because of the large projected attendance; it also mentions the ongoing gatherings of the London SF Group at the White Horse Tavern.

* * * *

Overall, the quality of the fiction improves after the first three issues.

The inane, the archaic, and the bloody awful still make their appearances, but they are a smaller part of the whole (John Russell Fearn is gone), and the median seems comparable to the median in the US pulps of the time, though not much is comparable to the best in those magazines. There are several stories by well-established British writers (Clarke with two stories, Temple and Beynon with one each), and some by newer writers who were flashes in the pan as far as New Worlds goes (John Aiken, Peter Phillips). What is interesting is the emergence of a substantial part of the stable of writers that would carry the magazine through most of the 1950s, including some who were virtually unknown in the US. In these issues the most prolific author is F. G. Rayer, with four short stories. A. Bertram Chandler—already well established, but also to become a New Worlds mainstay—has three, one under the George Whitley pseudonym. Sydney J. Bounds has two, and E. R. James’ first New Worlds story is here. Three of the stories had been previously published in US magazines, but one of them (Clarke’s “Guardian Angel” in 8) is explicitly said by Carnell to have been purchased more or less simultaneously in US and UK.

Issue 4, according to Carnell, contained the same fiction contents as planned for the fourth Pendulum issue.22 It leads off with “World in Shadow,” a novelette by the so-far-undistinguished John Brody. Fortunately, it’s a considerable improvement over his previous stories at the most basic level of readability—fewer malapropisms, overt clichés per square inch, etc. The story proposes that in the future, automation means nobody much needs to work, and more and more people are checking into the Mentasthetic Centres to live in a less boring dream world. What exactly goes on in the dream worlds is not explained—maybe they have dream jobs. Dick Maybach is one of the workhorses; he spends four hours a day running a nuclear power plant. He gets in his copter to hurry home to his bored wife, but:

“Move over, brother!” The voice came from the back of the cabin, a low, soft, voice that held a core of steel. “Don’t look back—and don’t argue. There’s a blaster six inches from your kidneys!”

It’s the Underground, trying to recruit him for their revolutionary scheme, which is to destroy the material basis of society so everybody will have to get off their butts and struggle—and, of course, Man Will Go To The Stars. (They already have all the parts of a spaceship, but in this decadent society nobody remembers how to put them together.) We get several pages of John Galt-ish exposition on how progress requires regress. Dick bites, since he’s afraid his wife, the beautiful Veronica, is about to succumb to the siren call of the Mentasthetic Centres. Conspiracy and hugger-mugger ensue; his wife does succumb, and Dick is presented with the world-historical choice: pull the levers that will blow up the power system and bring a new world into being, and also probably kill most of the millions of people who are jacked in at the Mentasthetic Centres, including his wife. Or not. He pulls the levers—“The Cold Equations,” UK style.

Or so it seems. Unfortunately the author does not quite have the courage of his bloody-mindedness. A few issues later, the lead story in 7 is Brody’s “The Dawn Breaks Red,” and here’s Veronica, big as life, but transformed. After the close of business in “World in Shadow,” Dick went to the local Mentasthetic Centre, where some 50,000 people were at risk of dying. There he found Veronica still alive, and made the doctor on duty, who was trying to save whom he could of the dying thousands, take Veronica out of turn by pointing a gun at him, and then spirited her out, noticing only later that her hair had turned white, and even later that she was demonstrating a remarkable intuition and ingenuity. Now, Veronica thinks it’s dandy that her husband pulled the plug on 50,000 dreamers and killed most of them.

The band of conspirators who brought down civilization have been hanging out in their redoubts Atlas Shrugged-style for a year, and they’re beginning to wonder what’s going on out there, and how all the folks whose lives they wrecked are getting along. So they set out for various destinations, and Dick and company go to his old house and encounter his neighbor. The neighbor is a trifle annoyed at Dick for killing his wife but is willing to let bygones be bygones. He explains that at the Mentasthetic Centres, most everybody died, but there were a few dozen in each whose hair turned white and who developed both enhanced intelligence and a cruel and calculating view of the world—like Veronica. The regular folks are getting ready to have a pogrom against these “whiteheads,” who are also referred to as mutants through the rest of the story.

The folks in the redoubts or “settlements” decide the whiteheads are the hope of humanity, and save them. (An unstated Lamarckian assumption is that people whose heads and follicles have been reorganized by pulling the plug on their artificial dreams will reproduce those characteristics rather than bearing ordinary human children.) However, hostility towards the mutants increases in the settlements, while Veronica has grown completely away from Dick. When the mutants take over, it transpires that they failed in one of the settlements, so the standard humans there are on their way with an aircraft full of atom bombs to wipe out the mutant-dominated settlements. Who ya gonna call? None of the mutants can fly a jet and none of the standard humans wants to save them—except Dick, who decides that only the whiteheads are going to make it To The Stars and he’s on their side; he dies in a kamikaze attack on the settlement aircraft.

It’s hard to see anything peculiarly British about this saga. The motif of rebellion against stagnation and the casual willingness to dispose of the fates and sacrifice the lives of thousands or millions pursuant to a self-appointed elite’s theory of history and progress seems pretty solidly in line with a lot of American SF, as does the notion of throwing in with a new mutant master race in the service of the unquestioned transcendent goal, The Stars.

* * * *

The other major feature in these issues is the continuation and conclusion of John K. Aiken’s series or novel that began in 3 with “Dragon’s Teeth.” There the peaceful and anarchistic Centaurians repelled the attack of the Galactic New Order, but they know another one is coming. In “Cassandra” (6), we learn that Vara, one of the sort-of-but-not-really governing group, and secondary protagonist Snow’s girlfriend, is in a coma induced by her horror at the violent self-defense of the previous story. A cat-like native race, the Phrynx, has fled to the Blue Moon, leaving behind instructions for building a peculiar machine, which turns out to be a Predictor, and it predicts the destruction of the colony world. Meanwhile, a supposed refugee from Earth has arrived and proves to be a spy; he obtains the Centaurians’ newly developed secret weapon, the hyper-explosive D, and nearly escapes to Earth with it. Luckily, one of the Centaurians has invented a thought projector and they subdue the spy with it. The Phrynx appear to Snow in a dream, announce that the crisis is afoot, and offer to straighten out Vara. This one is obviously an installment and not a story. (As previously noted, Carnell acknowledged in 5’s “Literary Line-Up” that the series is actually a novel broken into parts.)

Fortunately, “Phoenix Nest” is in 7, the next issue, and starts with a bang: Centaurus IV is beset with incendiary “seeds,” apparently courtesy of the Galnos, which start burning the place up. Anstar’s plan is to build giant thought-projectors and change the minds, literally, of everybody on Earth. But the Phrynx offer to evacuate everybody to the Blue Moon. Anstar, the primary protagonist, is forced from his leadership position and winds up alone on Earth building his giant thought projector while everyone else flees. In a dead-end subplot, his girlfriend Amber is kidnapped to the Blue Moon and makes it back just in time for the finale, in which they project their thought message to Earth. A few hours later they get the response that it worked, the Galnos have been overthrown, but not before launching a doomsday weapon that is going to blow up Centaurus IV and the Blue Moon in about two hours. All die, but not before Amber realizes everything has been in the service of the Phrynx’s master plan to hand over the universe to the decent (non-Galno) remnants of humanity elsewhere in the galaxy.

Overall this series is an ambitious nice try by a literate but inexperienced writer who doesn’t quite have the wherewithal to bring off a novel-length plot. Too much of what happens has an ex machina quality, there’s too much implausible super-technology cobbled together overnight (like a kinder, gentler, less noisy E.E. Smith) without much thinking through of implications (especially the Predictor), and the society of Alpha C IV never comes to life because all we see of it is the doings of eight or so characters in the foreground.

As noted earlier, these stories were fixed up (or this novel was reunited) into World Well Lost, published as by John Padget in the UK in 1970, but under Aiken’s own name in the US by Doubleday in 1971. A superficial look at the text shows that Aiken learned something in the intervening two decades. The stories have been comprehensively revised and updated stylistically and culturally; for example, Anstar’s observation to Amber in the first story, “You’re a tawny little fury when you’re angry,” fortunately has disappeared. Everything is described and explained more clearly. The plot seems to remain pretty much the same, including the demise of all the characters at the end. There is a note about the author on the back flap that is positively Pinocchian. After saying nothing about Aiken’s life and activities except that he moved to England young, graduated and got a Ph.D from London University, and now lives in London, it says: “Although World Well Lost is his first science fiction novel his writings have been published in all the well known science fiction magazines.” Well, there was that Probability Zero piece in Astounding...

Aiken had two more stories in New Worlds, one of them in these issues. “Edge of Night” (4), not part of the Anstar series, pleasantly executes a familiar plot. Three people are snatched from their times (arbitrarily, it seems at first) to enact a great destiny: Grierson, a submarine commander in trouble in 1942; Laura, a housewife tending her dying husband in 1940; Jimmy, a young working-class chap who was trying to get his child into a bomb shelter during the Blitz. They find themselves walking up a spiral ramp around a tower above the clouds. At the top of the tower, they find a captivating old man who introduces himself as Man (i.e., “the fusion of the minds of the last race of man”) and says his body is really Earth (he handwaves and it becomes visible beneath them). It seems that over the millennia, Earth’s elements “gradually built into denser, subtler ones” with atomic numbers “hundreds of times as great” as their predecessors (transcendence and cold fusion! This from a chemist, too, remember).

Now Man reveals the mission. These three people have been snatched from the past because they are the “minds most fitted to the task,” which is of course the struggle of good vs. evil. The Black Mind, which has taken over a large part of the universe, has become aware of Man, and has snatched Pluto in a cross between colonization and possession. The characters’ mission? To fly to Pluto in a spaceship designed to serve as a condenser for the projected mental force of Man (“some of the new heavy elements can focus thought”), for which they will be in effect a relay station. Where’s this spaceship? “‘Ah,’ said the old man. ‘That must be thought of.’” So he thinks it into existence, complete with galley stocked with stuff you couldn’t get in wartime London (“Butter, eggs, oranges—blimey, a pineapple—never ’ad one in me life!” says Jimmy) and they’re off.

It takes about three hours to get to Pluto, or at least to get past the orbits of Jupiter and Saturn, and once there they engage, or are used by Man, in a typical science fictional mind battle, which they of course win. Pluto blows up. Back on Earth, Grierson and Laura declare their love, though the latter says she won’t leave her husband if he pulls through. Man breaks it to them that he has to wipe the memories of the two from 1940 because they mustn’t retain what they’ve learned about 1942, so Grierson says he’ll look her up if it turns out her husband died, and he’ll look Jimmy up too and get him into the Navy, assuming Grierson survives the depth charges (but it looks as if he won’t). This absurd fairy tale is made reasonably enjoyable, indeed charming, by competent and matter-of-fact writing and appealing characters, including Man. It would have been right at home in the back pages of Thrilling Wonder Stories.

* * * *

The lead story in 8 is Arthur C. Clarke’s “Guardian Angel,” later incorporated into Childhood’s End. It was written in July 1946, bounced by Campbell at Astounding, rewritten, and sent to agent Scott Meredith to sell; he had it revised by James Blish and it was first published in Famous Fantastic Mysteries, April 1950. In it, Stormgren, the Secretary of the United Nations and effectively world president, deals with Karellen, the representative of the extraterrestrial race that has brought its civilizing mission to Earth. Karellen will not show himself. Why not? Famously, because he looks like traditional renderings of Satan, and people would talk. New Worlds uses Clarke’s original text and not the Blish revision, though not out of any agenda. Carnell says in 10 that the story was sold to him and to the US magazine at the same time, but the latter got it into print two months earlier.

Clarke says he thought Blish’s ending was “rather good,” but he didn’t find out about the revision for a long time.23 The revisions, overall, are relatively minor, consisting mostly of cuts of sentences and paragraphs from Clarke’s version, including the removal of some internal framing material. The “new ending” actually just repeats a few lines of dialogue from earlier in the story that sharpen the analogy to Satan. Neither version is particularly interesting nor impressive, though both are capably written; in the novel, this material served mainly as set-up and seemed to me a bit of a distraction even before I knew it had been published separately. It is not entirely surprising that this story took second place in the readers’ poll to a short story by an unknown writer.

Of the non-featured fiction, Clarke’s “The Forgotten Enemy” (5) is probably the best known, minor as it is, and the last piece of non-reprinted Clarke fiction in New Worlds until 1958. In one of his short and quietly elegant early pieces, the glaciers return to London.

The best story in these issues may be Peter Phillips’ “Plagiarist” (7), a high-quality museum piece set in a Bradburyesque future in which the irrational and atavistic have been banished from human culture. The protagonist is the imaginative young rebel who finds a time capsule and tries to flog Beethoven and Shakespeare at his rite of passage performance. Nobody much likes them, and they accuse him (correctly) of plagiarism and kick him out. Though ultimately the story is a bag of conventional sentiments, it is quite well turned and presents a pharmaceutical grade sample of one of the great tropes of SF of the late ’40s and the ’50s. The readers voted it best in the issue.

Phillips’ other story here, “Unknown Quantity” (5), is equally facile but considerably more annoying, a pseudo-think-piece in which a religious figure known only as the Preacher rants against the “soulless” Servotrons, i.e. androids, prompting the company that makes them to challenge him to a philosophical debate. The joker is that the company trains a Servotron to do it, named Theo Parabasis no less,24 and then to reveal his provenance after the debate. But the Preacher, too, is really an android put up by a rival company to help drive down Servotron’s stock. When Theo exposes his nature, the Preacher declares Theo his equal (“His God is my God—and yours, if you have wit to reason. For does not all reason reach toward God?”) Then the Preacher reveals his own androidicity, explaining later to his handler: “There comes a qualitative change in a brain when it is given so much knowledge. A subtle change. True reasoning begins. And something is born. A soul. I found that I had a soul.” Later, we see Theo playing the piano again—this time, with expression.

The reason this one is annoying is that it raises a significant question about consciousness and then buries it in unexamined sentimentality, worse than not asking the question at all—a sort of cogitus interruptus. (For a considerably better time on this subject, which I happened to read around the same time, see Ken Liu’s “The Algorithms for Love,” from Strange Horizons, reprinted in the 2005 Hartwell/Cramer Year’s Best SF 10. It doesn’t answer the question but it doesn’t obscure it either.) Carnell, however, thought enough of “Unknown Quantity” to anthologize it both in The Best from New Worlds Science Fiction (Boardman, 1955) and No Place Like Earth (Boardman, 1952).25

Phillips (b. 1920) is probably two-thirds of the way towards Little Known Writer status even among SF cognoscenti. His career, boosted early by the immensely popular “Dreams Are Sacred” in Astounding in 1948, comprised 22 stories from 1948 to 1957, all but two appearing by 1954, starting with a couple in Weird Tales. Most of them appeared in the US magazines, and most of those in Astounding, Galaxy, and Fantasy & Science Fiction. “Lost Memory” may be the best of them. “Plagiarist” is the last original Phillips story to appear in New Worlds, though his last story, “Next Stop the Moon,” was reprinted in New Worlds after appearing in 1957 in the London Daily Herald. He never managed a collection, and “Dreams Are Sacred” is the only story of his that has been reprinted since 1990.

The oddest item in these issues is undoubtedly William de Koven’s “Bighead” (8), a definitive send-up of the genre. In the future, the Brooklyn Movement puts mediocrity in the saddle, until there is a counter-revolution based on brain size. Things were crude at first. The founder explains: “I had to go by hat-size and age.... Unfortunately, this eliminated those whose heads were tall but small in circumference.” Later, more refined methods were developed, relying on cranial capacity, ability to hold one’s liquor, and absence of certainty on questions of life, death, and fate. Now the Bigheads lord it over the Pinheads. But Bighead Zircon defies his father Pluton for the love of a Pinhead girl, Threnda. After they are married, Pluton’s agents go after Threnda, who survives a personality-tuned ray-ship attack only by discarding her clothes (“Clothes are part of the personality. Without them we are not the same. The magnetic emanations of an industrialist at a board meeting are not those of the same man in a bath-tub.”) So it’s war.

The Pinheads head to Mars, with Zircon sworn to help them. He learns he’s being used and Threnda is one of the betrayers; but with the help of Melissa, who is undercover as the chief Pinhead’s secretary (“She reached into the roots of her hair, extracted a tiny badge which fastened with a clip. ‘Melissa, Operative Q-47 of the Bighead Secret Police.’”), Zircon wins through. Peace is in sight. This one sat in inventory for several years; it was advertised in 3 in 1947 as coming next issue. The often humorless Carnell apparently did not know quite what to make of it, as witness his solemn blurb (“It was an old problem—a minority with brains and power, against a majority only endowed with numbers—and corruption.”) The readers didn’t either. They voted it into last place. Carnell later wrote that de Koven “was a pseudonym for a then well-known American author but neither my memory nor records throw any light on his true identity.”26

* * * *

A. Bertram Chandler, who published 23 stories in New Worlds under his name and the George Whitley pseudonym, has three stories in these issues. The best, as by George Whitley, is “Castaway” (6), reprinted from the November 1947 Weird Tales. The protagonist, on a ship investigating smoke signals from a Pacific island, suddenly finds himself struggling alone in the water, barely makes it to shore, and when he looks for whoever lit the fire, finds a derelict spaceship from the future, complete with Mannschen Drive and its time-distortion properties. He can’t keep his hands off it, and shortly finds himself in the water again. This is one of Chandler’s better stories, tight and nightmarishly vivid.

The other two are less pointed but typically ingratiating. “Position Line” (4) is an agreeable piece of the nautical geekery that Chandler thrived on for years. On Mars, a spaceship crash has taken out the spaceport and power plant and a lot of people need rescuing fast from the other colony town. The only way is a fleet of Diesel sand cats—but how to navigate across the desert, in this yesterday’s tomorrow without GPS? The protagonist, a dissatisfied policeman, formerly an equally dissatisfied mariner who came to Mars because sailing had become so automated, breaks out the bubble sextant he brought along, and it’s George O. Smith in two dimensions for the rest of the story. This is probably the most mundane story in the issue in terms of science fictional ideation and action, and it’s also the one the readers voted best in the issue.

It is followed by “Coefficient X,” in 6, another navigational opus. On Venus, which has lots of oceans, compasses have stopped working reliably, and ships are getting lost. The protagonist is a compass expert from Earth, and he finds the problem. There are creatures called “loofards,” combinations of loofah and lizard (honest), which the Venerians (here called Hesperians) like to take into the bath with them—for exactly what is not explained, though the loofards do like to eat soap. They turn out to have iron in their bones and to generate magnetic fields, a bit like an electric eel. But there is more going on than this rather arid (well, humid too) gimmick. According to Chandler, Venus is multiracial: “Venus was a huge melting pot in which white and yellow, black and brown, were being blended. The results were—pleasing. The ability to live, to play, of some of the coloured folks lost nothing by admixture with the drive—on Earth so often squandered, so often without a worthy objective—of the whites.” Later on, the ship’s Calypso Man, known as Admiral Stormalong and “not overly dark,” sings a song in the compass-mender’s honor, beginning:

“Eber since de worl’ began

De compass am de frien’ of Man...”

There is also gender politics. The ship’s captain already knows it’s the loofards who are causing the compasses to go awry, but they need to get an expert from Earth to say it (and then to leave hastily) because the women are “the inevitable product of a combination of pioneering and all the comforts of civilization. They’re spoiled here, utterly spoiled.... But they’re powerful.” And they like the loofards and oh, by the way, Voodoo has been reestablished, so the protagonist had better get off the planet fast if he knows what’s good for him, and thank you very much.

A couple of other big names make lackluster contributions. John Beynon’s “Time to Rest” (5) is a well written but sentimental story in which not much happens. Earth has blown up, stranding humans on the other planets, and Bert, who sails the Martian canals in his homemade boat, drops in on the Martian family he is friends with; notices that their daughter is getting grown up; gets nervous and leaves. Her mother says he’ll be back. (And he is, in the sequel, a year or so later.) This one is reprinted from the Arkham Sampler of 1949. Beynon a.k.a. John Wyndham was not really a New Worlds mainstay; he published about 10 stories in it over the years, most notably the “Troons of Space” series starting in 1958, which became The Outward Urge.

William F. Temple’s “Martian’s Fancy” (7) is a piece of slapstick, overlong and tiresome, about a space captain who brings his half-breed illegitimate Martian son home to Earth for a visit with the family, wringing yocks from such matters as the housekeeper’s hirsuteness. Temple made only five appearances in New Worlds. Though prolific, he spread his work around.

* * * *

One of the pillars holding up these issues is F. G. Rayer, who previously had an archaic but pleasant item in 3 and a story in Gillings’ Fantasy in 1947. He is a Little Known Writer of a peculiar sort, the quintessential New Worlds homeboy, once very well known in the UK but pretty much unheard of in the US. According to Miller/Contento, from 1947 to 1963, Rayer (1921-81) published some 58 stories in the UK magazines under his own name, eight as by George Longdon, and one as by Chester Delray. Over half of these were in New Worlds. After Carnell left New Worlds, that was it for his SF career. Except for the US reprint of New Worlds, he appeared in the US magazines only three times, each time with a story that also appeared in the UK (though one of them made it into print first in the US). His anthology appearances, few and long ago, were in UK books with no US editions, except for one George Longdon story in an old Andre Norton anthology. Rayer also had a few novels published, one of which, Tomorrow Sometimes Comes, actually made a bit of a splash, but none of them had US editions either.

Rayer is profiled in New Worlds 33 (March 1955), and it seems that his SF was only the tip of an iceberg: he had allegedly published over a thousand stories and articles in at least 53 publications, mainly SF and “scientific articles.” So he must have been a prolific science journalist somewhere. Rayer subscribes to Fans Are Slans: “I think the reading of present-day science fiction demands a certain mental liveliness and I would put readers of it as being generally of a higher intelligence level than average readers of other classes of fiction.” The profile declares Tomorrow Sometimes Comes to be his “most outstanding piece of fiction,” and Rayer says it “will remain the most personally satisfying, having also been translated and published in France and Portugal.” (In an autobiographical piece for a fanzine,27 Rayer recalls “the pleasure with which I received Olaf Stapledon’s most high and generous praise” of the novel—even better than being published in France and Portugal, I would think.) I read Tomorrow Sometimes Comes a few years ago after visiting Australia and finding it awash in old paperbacks of the book. It is a post-nuclear war novel that runs the changes on big questions of human destiny vs. stagnation, freedom vs. regimentation, etc.—a bit stuffy but a respectable try, much better than the stories described below in these issues of New Worlds. Carnell reviewed it in 10 and described it as “undoubtedly the finest British science-fiction novel published in this country in recent years.”

In his fanzine bio, Rayer says the best-remembered SF of his childhood was Scoops, back issues of which he borrowed from his cousin E. R. James, and he searched out Wells and Stapledon, the latter of whose “narrative style does not attract those who were more accustomed to minute paragraphs and endless (and often pointless) action.” He dislikes “women dragged into stories for the sake of the feminine or romantic interest; pictures of the latter undressed yet unfrozen in space, etc.; stories based on series of ‘clever’ incidents which do not really integrate. Admired traits are: real originality, fully reasoned and logical development, scientific premises which will stand pondering upon, and lack of superficial emotion.” He thinks SF should be at least as logical as detective stories. He continues:

These feelings, strong as they are, may have arisen from the large amount of work I do on electronic equipment; here, there is always a reason, though sometimes complex deduction is required to discover it.... At present, should the Editor see a mobile device come along the road, halt, survey him with an electronic eye, then withdraw, he will know that one of my radio-controlled models is on reconnaissance.

So was the prolific Rayer an exclusively UK writer for nationalistic reasons, or could he just not sell to the higher-paying US markets? On the basis of the stories here, either is possible. They are an exceedingly mixed bag. The best of the lot is probably “Quest” (7). Konrad, spaceship captain, has been tossed overboard by Everard, his thuggish second in command, but spots and manages to board an ancient alien spaceship. A telepathic voice tells him he’ll do fine for the job. (What job?) Everard and his sidekick show up at the airlock; the ship blew up after they got rid of Konrad. They’ve all got about 17 hours’ oxygen. They black out and wake up with the ship down on a world full of dust. A robot greets them, explains that its creators had split into physically competent and pure brain factions, but the former were wiped out in a plague, so the pure brains sent out spaceships to try to find new helpers for them. (That’s the job.) At their request, Konrad finishes assembling a machine they need, then asks to be sent back to Earth. The masters refuse, denounce mobile life as useless, and start to fry the robot. Konrad pulls it out of harm’s way and it expresses its gratitude. Everard, who has been skulking about, tries to ambush Konrad for his remaining oxygen, and the robot saves Konrad. They head off to Earth, Konrad to be put in suspended animation for the voyage since he’s running out of oxygen; he wonders whether he will arrive in a present he’s familiar with or in the far future. This is hardly great literature but there is plenty of plot and imagination in relatively few pages; it gives good pulp weight.

“Necessity” (5) is about as well done, though a bit more obvious. Captain Pollard of the Star Trail Corps is expounding his theory that all life is interrelated when his spaceship is drawn inexorably to Xeros II. It lands in a clearing in a heavily vegetated area and can’t take off again, for no apparent reason. The crew explores, but the plants don’t cooperate; breaks in the forest close before the crew can get to them, keeping them in the clearing. There’s a nasty-looking gray weed patch encroaching on the other plant life, and while they sleep it starts to envelope the spaceship. So they break out the weed killer and dispatch it. Suddenly the engines work again and they can leave. They’ve done what the other plants needed and brought them in for. Pollard’s theory is vindicated. Here Rayer tries out his chops as a stylist, and he’s not too bad in an overdone sort of way: “There was something so pathetic about the melody of the leaves that it was with a feeling of inexpressible melancholy that he at last fell asleep. It were as if the trees were telling of some long-drawn, secret agony which sapped their life, leaving them listless except to tell of their misery in the evening cool.”

The other two Rayer stories are a more rancid kettle of fish, with pretty serious defects of logic and plausibility. In “Adaptability” (6), in “the gigantic factory which was being built to mark the dawn of the 21st century—the beginning of an age of new mechanical and scientific wonder,” funny things are happening. A strange light appears, there’s a spherical vehicle from which grotesque forms appear and quickly disappear into the nearby woods; people give chase but just when they think they have one, it turns out to be a branch or a tree stump. Somehow, there seem to be more X-M units (whatever they are) than anyone ordered. So they analyze samples of all the X-M units. They’re metal, all right. The protagonist, a big wheel (not a cog) in the factory, does the only sensible thing—he lurks, and when the vehicle appears again and the grotesque forms have disembarked, he leaps into it and gets taken whence it came, which proves to be an extradimensional world full of the aforesaid grotesque forms bent on world conquest—all the worlds—through their uncanny imitative ability. He learns this because they are telepathic and he eavesdrops; somehow he keeps his own thoughts under control and manages to hijack the vehicle back to the home dimension, where he and the factory crew take all the X-M units—which he realizes are disguised aliens who have managed to adjust their molecules as well as their outward form—and put them to the test of heating inductors, killing the invaders. A homemade bomb thrown into the vehicle on its next pass completes the defense of humanity.

The worst of the lot is “Deus Ex Machina” (8). It is the first of Rayer’s “Magnis Mensas” series, which comprises five stories over 11 years in New Worlds and Science Fiction Adventures, and which also includes the above-mentioned novel Tomorrow Sometimes Comes published the following year, though there the eponymous world-dominating computer is called Mens Magna. In “Deus Ex Machina,” an employee of Subterraneous Architects is accused of criminal negligence, charged with murder, and sentenced to death at the instance of Magnis Mensas, which saw the whole thing, and which is allowed to testify without oath, since the oath would be meaningless to a machine and machines can’t lie anyway.28

After the trial, several people—the employee’s boss, his fiancé, his lawyer—point out to Magnis Mensas that since it did see the whole thing, its failure to warn the deceased is equally culpable. MM locks them up so they can’t tell anyone else. (Why they didn’t point this out during the trial is not explained.) Why is MM doing this? For the good of humanity. The employee was directing an excavation that shortly would have discovered the existence of “negative matter vessels and negative matter beings,” and it would cause mass neurosis to “let man know his Earth is honeycombed by beings a hundred times more powerful than himself.” But Padre Cameron puts a bug in MM’s ear about how humans swear before an Ideal (a.k.a. their Maker) and how terrible it is for humans to die unready to meet their Maker (connection of the latter point to the story is a bit unclear). Problem solved! MM brings forth the prisoners and gets them to swear they won’t tell a soul about negative matter vessels and beings, and lets them out.

E(rnest) R(ayer) James is almost Rayer’s shadow, as well as his relative and sometime collaborator—prolific, though not as much as Rayer, with 42 appearances in the UK SF magazines (the respectable ones—New Worlds, Science Fantasy, Authentic, Nebula), from 1947 to 1963. His only appearances outside the UK consisted of two stories reprinted in the US edition of New Worlds. This story is his second, following a first appearance in Gillings’ Fantasy in 1947. He seems to be another writer whose career was effectively ended by Carnell’s departure from New Worlds and Science Fantasy. He had a couple more stories in a 1947 UK-only original anthology or collection called Worlds At War (which also had some Rayer stories), and his couple of anthology appearances were in UK-only books. He has no entry in the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and therefore presumably has not published a novel. So to those who go back a ways with British SF, he is probably reasonably well known, but otherwise, not. He might be described as the UK equivalent of, say, Winston K. Marks, author of many forgotten SF stories.

James did have a low-level second career, with another seven stories in Dream, New Moon, Fantasy Annual and Gryphon SF and Fantasy Reader from 1987 to 1998, all minor markets and several of them semi-professional low-circulation nostalgia operations. Miller/Contento has no dates for James, but New Worlds 37 (July 1955) has a profile of him, indicating he was 34 (therefore b. 1921, presumably). It says he started “to seriously plan a semi-literary career” in 1947, having survived Normandy blinded in one eye. “To this end he took a job as a postman in a rural Yorkshire area where he and his wife live because ‘I have found,’ he states, ‘that postal work fits in with a career of part-time writing very well. In fact, I declined an offer of an indoor clerical appointment in the Post Office because I felt that the outdoor work left my mind less exhausted and more eager for thinking up stories.’” Carnell adds: “With the courage of such convictions he has now sold over thirty-five stories....”

James’ “The Rebels” (4) is a scenery-chewer of the Planet Stories ilk. On a spaceship of a viciously hierarchical society, the likes of the Master Minder and the Overseer lord it over the crew, which is always terrified of falling into the Redundant Class. But the downtrodden stage a mutiny, hoping to divert the ship from its destination to the Independent City on Efferenter II. The plans go awry, they fail to kill all the big shots, and they wind up in a bloody free-for-all that ends in blowing the ship in half. Three survivors manage to crash-land their half-ship on Efferenter III, which is no help at all, but they figure out how to prop up and lash down the gyroscope so they can point in the right direction, fill the ship with helium so they can get off the ground with the aid of E.III’s high rotational velocity, and they’re on their way to E.II and freedom. It is a crude but grimly enthusiastic piece of blood-and-thunder storytelling.

Sydney J. Bounds (1920-2006), who had 16 stories in New Worlds over the years, published a total of about 70 in the SF magazines, remaining active as late as 2002 (though most of his output after the demise of Vision of Tomorrow appears to be in semi-professional venues). He too seems to have been a UK-only writer, with one sale to Fantastic Universe in the 1950s, but no more to the US magazines. His stories under his own name appeared in the higher-rent UK magazines—New Worlds, Science Fantasy, Nebula, and Authentic—but he also used a number of pseudonyms to publish in the downmarket ones like Worlds of Fantasy and Futuristic Science Stories, to which he contributed a story actually titled “Vultures of the Void.” He published a few paperback SF novels in the 1950s as well as confessions, juvenile, gangster and western fiction, according to his profile in New Worlds 32 (February 1955). He was a member of the late ’30s London circle that included Arthur C. Clarke and William F. Temple, and became a full-time writer in 1951, leaving a job as sub-station assistant on the London Underground. The profile says: “Still unmarried he prefers to smoke a pipe and paint pictures for relaxation—and prefers art to be spelt with a small ‘a’.”

On that last score, one cannot accuse Bounds of hypocrisy. “Too Efficient” (5) is a piece of pleasant yard goods: protagonist discovers his newly purchased electric motor is working at 107% efficiency, goes to the company to investigate. Of course they’re stranded aliens trying to raise enough money to get off the planet. These high-efficiency engines really have nuclear power plants concealed inside them. The aliens kidnap the protagonist to their spaceship, which is underwater. After they depart, releasing the protagonist, he heads home, gloating that he is in possession of “the secret of space travel!”

“The Spirit of Earth” (8) takes a great leap downward, however: it’s a displaced French Foreign Legion story set on Mercury that is best allowed to speak for itself. Here the Captain, disgraced and exiled of course, is assembling a rescue party for a crashed spaceship:

The Captain felt a pride in his men, a pride he had once felt in very different circumstances, and had never thought to know again. He walked slowly down the ragged line, picking his men.

“Long Tom.”

A gangling frame of creaking bones and mahogany skin straightened up. The gaunt face smiled, smiled as it had once under twin Martian moons, treading the red desert.

“Shilo.”

A squat figure shifted from one splayed foot to another. A light flickered deep in yellow eyes—eyes that had looked out over the hideous landscape of massive Jupiter.

“Sturm and Jeri.”

The brothers’ dark, impassive faces revealed nothing. They might have been volunteering to make up a foursome at space poker—or booking a return passage to their native Venus.

“Blacky.”

Once he had been a space jockey, riding Saturn’s rings: now he was just one more derelict at Outpost Sunspot, the dumping ground for broken men, the end of the journey from which there could be no return.

“Adoption” by Don J. Doughty (6), his only appearance in the SF magazines, competently rings a change on a standard plot: Johnny has an imaginary playmate Bugs, but Bugs proves to be real, from a pretty horrible future, so when he comes home with Johnny and then can’t get back to his own time, Johnny’s parents are happy to take him in.

J. W. Groves’ “Robots Don’t Bleed” (8) recapitulates Lester del Rey’s mawkish “Helen O’Loy,” this time as spite. Space pilot meets girl as a result of the lifelike robot rabbits she makes. They want to get married but he needs money, so he spaces out again (as it were) for a year, and when he gets back, there she is to meet him, except he figures out it isn’t really she when a spaceship crash-lands on her and she isn’t hurt. She’s made a lifelike robot of herself to occupy him, and meanwhile she’s married someone else. So he heads back to space with the robot (“If it was good for nothing else, at least it could do the chores.”). But he gets homesick, and returns and drops in on his ex-fiancé, who has grown fat and snobbish and has reduced her formerly spacegoing husband to puttering around making toy model spaceships. So it’s outward bound into the great void again, with his robot, no return planned. Carnell liked this one enough to anthologize it twice, in No Place Like Earth and The Best From New Worlds. Groves (b. 1910) published a dozen stories in the SF magazines in a curiously symmetrical career: one in 1931, 10 from 1950 through 1954 (one in Astounding, the others in the US pulps), and one in 1964. He also published two belated novels in the late 1960s, Shellbreak and The Heels of Achilles.

Ian Williamson’s “Chemical Plant” (8) belongs to a common subgenre in New Worlds and many other SF magazines: send the characters to a newly discovered planet and set them a technical puzzle. See Rayer’s “Necessity,” discussed earlier in this chapter, for another very similar example. Here, a spaceship lands on a planet covered with vegetation, near five lakes all of which have differently colored water, then disappears. Investigation by would-be rescuers reveals that the world-plant was extracting chromium for nourishment. The lakes are different acid baths, and the spaceship is a huge and tasty morsel that the plant humped into one of the lakes by selectively growing. There is a stereotypical clash between the pompous captain who wants to blast everything and the nice captain who gets down on the ground and turns over rocks to find out what is going on. It’s not badly done, and the readers put it first in the issue, ahead of Clarke’s “Guardian Angel.” Carnell anthologized the story in No Place Like Earth, and said: “Ian Williamson denies all credit for the story under his name, stating that it was actually written by a logical-computing machine which is kept in a cellar near Manchester University. As a physicist he stumbled across this ‘captive’ machine quite by accident—it had been built by a scientist who could prove that he was sane and the rest of the world quite mad. As nobody is likely to believe Mr. Williamson’s statement, he is quite happy in the knowledge that he can go on using the machine to further his own literary ideals.” It must have blown a resistor or something; Ian Williamson has no other credits in the SF magazines.

Norman Lazenby’s “The Cireesians” (4) is an amusing if incompetently written tale of transcendence. It seems Earth humans originated in an unauthorized bio-engineering experiment by one of the true humans of Cirees, and they were hastily dumped on the young planet Earth along with a conscience-stricken Cireesian who helps them survive, contemporaneously with dinosaurs. Eventually they evolve into us, and we head out to the Lesser Doriad Cloud, where our boys encounter the remaining Cireesians, who introduce themselves as Gods, having long since disembodied themselves. Big mistake, because now they are helpless: “We are pools of pure thought needing the reviving fibres of crude humans.” But they have a plan: “We will infest your body and then reproduce from you, rapidly and with incredible variation, a new being who will be a biological combination of your two sexes.” They say, “We are entitled to you.” Why? Because their representative stayed on Earth and helped us out hundreds of millions of years ago. But the humans outsmart the Gods and defeat their scheme. Think of it as a cautionary tale about the Singularity. Norman Lazenby (1914-2003), by now a thoroughly Little Known Writer, had appeared a few times in Walter Gillings’ Fantasy in the ’40s, had nothing more in New Worlds, but published a couple of dozen stories, mostly in the (reputedly) really trashy UK magazines like Tales of Tomorrow and Futuristic Science Stories in the 1950s, and contributed such pseudonymous items to the early ’50s downmarket paperback boom as The Brains of Helle, attributed to Bengo Mistral. He had a couple of stragglers in Vision of Tomorrow and Fantasy Booklet much later.

The bottom of the barrel is shared by W. Moore (not the talented Ward Moore, US author of the celebrated Bring the Jubilee, and this byline does not reappear) and by Francis Ashton. Moore’s “Pool of Infinity” (5) is an inane prepubertal-shaggy-God creation story in which Isosceles and Equilateral fool around with a new mixture Daddy has whipped up, and splash some droplets around. “Jet Landing” by Ashton (6) is a brief and geeky lecture revealing the difficulty of landing a rocket on its tailfins without a stern periscope. That byline appears only in two other stories in Super Science Stories in 1950 and 1951. However, Ashton (1904-94) also produced several novels: The Breaking of the Seals (1946), allegedly a theological fantasy; Alas That Great City (1948), allegedly a sequel, having something to do with Atlantis; and The Wrong Side of the Moon (1952, with Stephen Ashton), an SF novel that Carnell (in 14) found to be of some merit.

19. Carnell recounted that Pendulum’s £80 check to him for the third issue bounced, was reissued, and bounced again, and when Carnell again went to the Pendulum offices, no one was there except Stephen Frances, clearing up for the receiver. All he could offer Carnell was a suitcase full of copies of the magazine, which Carnell later sold on the collectors’ market, recouping his loss more than a decade later. Carnell, “The Birth of New Worlds,” Vision of Tomorrow, October 1970, p. 63.

20. Harbottle, Vultures of the Void: The Legacy, p. 85. See also Frank Arnold’s article “The Circle of the White Horse,” in New Worlds 14.

21. See these covers at http://www.sfcovers.net/mainnav.htm or http://www.philsp.com/mags/newworlds.html.

22. Harbottle, Vultures of the Void: The Legacy, p. 85.

23. Except for Carnell’s statement, this is sourced from Neil McAleer’s Arthur C. Clarke: The Authorized Biography (Contemporary Books 1992).

24. A parabasis is a point in the play when the actors leave the stage and the chorus addresses the audience directly.

25. No Place Like Earth is an anthology of SF stories by British writers, some reprinted from New Worlds and others from the US magazines.

26. Carnell, “The Birth of New Worlds,” Vision of Tomorrow, September 1970, p. 63.

27. F. G. Rayer, “Science Fiction Personalities,” Space Diversions 6 (April-May 1953), at http://www.fanac.org/fanzines/SpaceDiversions/SpaceDiversions6-04.html (visited 9/8/11).

28. In the Anglo-American legal system, criminal negligence, even resulting in death, is entirely different from murder, so the idea that they would be equated and the former treated as a capital crime in any recognizable future variant on that system is absurd.