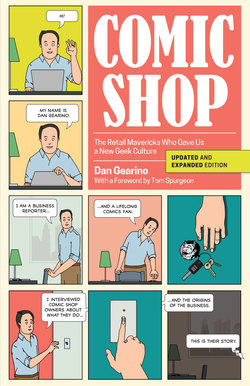

Читать книгу Comic Shop - Dan Gearino - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

Magical Powers

ON A Saturday, Gib Bickel sees a woman step into the children’s section of his shop. He approaches and gives his usual opener: “Canwehelpyoufind-something?” The woman, with tattoos down both arms, is shopping for a graphic novel for her daughter. She has no idea what to get, although a book called Hero Cats has caught her eye. He points her toward something else, a favorite of his, Princeless.

“This girl, she’s a princess,” he says. “Her dad puts her there in a tower with all her sisters until a prince will rescue her, and there’s a dragon guarding her. And then she’s like, ‘Why am I going to wait around for some dumb boy?’ So she teams up with her dragon and they have adventures.” Sold.

Bickel has hand-sold more than one hundred copies of Princeless, a small-press graphic novel that has become a cult hit and been followed by several sequels. This is what he does. It is what makes him happy.

He is in his midfifties, with a graying goatee and a wardrobe that is an array of T-shirts, shorts, and jeans. And he is an essential part of the Columbus, Ohio, comics scene. In 1994, with two friends, he founded The Laughing Ogre, a comic shop that shows up on lists of the best in the country. Though he sold his ownership stake years ago, he still manages the shop and can be found there most days.

Laughing Ogre is one of about 3,200 comic shops in the United States and Canada, mostly small businesses whose cultural significance far exceeds the footprint of their revenue.1 They are gathering places and tastemakers, having helped develop an audience for Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles in the 1980s, Bone in the 1990s, and The Walking Dead in the 2000s. And yet, for all the value that comic shops provide to their communities and to the culture, their business model has a degree of difficulty that can resemble Murderworld, the deathtrap-filled amusement park from Marvel Comics. Publishers sell most of their material to comic shops on a nonreturnable basis. By contrast, bookstores and other media retailers—some of which sell the same products as comic stores do—can return unsold goods for at least partial credit. The result is that comic shops bear a disproportionately high level of risk when a would-be hit series turns out to be a dud. And there are plenty of duds.

This book is a biography of a business model, showing comic shops today and how they got here. I come at this as a reporter who covers business, and as a lifelong comics fan.

Before going on, I need to define one important term: “direct market.” The current comic shop model was born in the 1970s, and it came to be known as the direct market because store owners received comics straight from the printers. Before that time, nearly all material had to be bought from newspaper and magazine distributors. Today, the network of comics specialty shops are still called the direct market, although the “direct” part has not been accurate for a long time. More on that later.

The staff at Laughing Ogre, and at shops across the country, let me into their worlds for what turned out to be a tumultuous year, from the summer of 2015 to the summer of 2016. The two major comics publishers, Marvel and DC, did most of the damage, with many new series that did not catch on, relaunches of existing series that often failed to energize sales, and a months-long delay for one of the top-selling titles, Marvel’s Secret Wars. The notable failures were almost all tied to periodical comics, single issues of which cost $3 to $5 apiece and are sold mainly to people who shop as a weekly habit. In other words, the leading publishers spent the year pissing off some of their most loyal customers and undermining their retailers. And yet, much of the sales slide was offset by growth of independent publishers and by small hits such as Princeless, big hits such as the sci-fi epic Saga, and many in between.

Amid the ups and downs, comic shops have a knack for launching ideas into the broader culture. Few do this as well as The Beguiling in Toronto. One example was in 2004, when a recent former employee had a book coming out from a small publisher. The store’s owners had a launch party at a nearby bar, and about fifty people came. There was no reason to think the book would be a sales success, but the people at The Beguiling wanted to support their guy, and they loved the book: Scott Pilgrim Vol. 1: Scott Pilgrim’s Precious Little Life by Bryan Lee O’Malley. That night, the entertainment was provided by O’Malley’s garage band.

“It was going to be a blip as far as I could tell,” O’Malley said. His publisher, Oni Press, had told him that preorders of the book were about six hundred copies, which was respectable but not great. He had no plans to quit his day job at a Toronto restaurant.

In the weeks that followed, The Beguiling sold the book with an evangelistic passion. Selling Scott Pilgrim was easy because the book was great, said the store’s owner, Peter Birkemoe. Grounded in the real Toronto and sprinkled with bits of fantasy, it told the story of a young man getting his life together and falling in love. The artwork was strongly influenced by Japanese comics and the aesthetics of 1990s video games. Scott Pilgrim became a sales success at a few stores across North America, which built word of mouth and turned the book into a sensation at other comic shops and then in the bookstore market.

As of 2010, Scott Pilgrim had completed its seven-volume run and had more than one million copies in print in North America, according to Oni Press. That was the year the movie adaptation, Scott Pilgrim versus the World, was released. “I’m convinced that Scott Pilgrim will go down as one of those series that changed comics forever,” said Joe Nozemack, Oni’s publisher, in a 2010 news release. “When I’m out and see someone wearing a Scott Pilgrim T-shirt or sitting in a cafe reading one of the books, I get so excited about comics entering the mainstream and to know that Oni Press’s books are helping lead the way, it’s an indescribable feeling.”2

By the time the movie was released, O’Malley had long since quit his day job to be a full-time comics creator. He remains grateful and a bit baffled that his book, of all books, was the one that made it big when many great ones do not. “There’s no way it was going to be a success without this kind of network of people who were going to be enthusiastic about it. I didn’t see it coming at all,” he said.

The best comic shops have a connection with their customers that leads, repeatedly, to some artists and series bubbling up to prominence. This dynamic also plays out at the best independent bookstores and record stores. The difference is the way that many comic shop customers make weekly trips, allowing shop owners to get to know their clients and what they want to read.

“We’re bartenders,” said Brian Hibbs, owner of Comix Experience and Comix Experience Outpost, both in San Francisco. “We’re the friend that you come to and go, ‘What’s on tap this week?’” He is one of the leading comics retailers of his generation, and played a role in the rise of several creators, such as Neil Gaiman, whose Sandman, from DC Comics, began in 1989, the same year Hibbs opened his store. “We’re selling to alcoholics, essentially. We’re there to solve their problems and take the burden of their lives away for a few minutes.”

At first, I thought this book would be about comic shops facing an existential challenge as the country shifts away from print media and as Amazon and other mega-retailers continue to take market share. I learned, however, that the industry has had a nausea-inducing level of volatility almost since it began in its modern form in the 1970s. So yes, comic shops are at a crossroads, but they find themselves in a similar situation every few years. What is interesting is how this crossroads is different from the others.

To begin to answer this question, I went to Milton Griepp, an industry veteran and chief executive of ICv2.com, a website that covers the business of comics and pop culture. “The biggest force affecting comic stores right now is the demographic diversification and taste diversification of the audience,” he said. “You’ve got women in sort of unprecedented numbers reading comics. We haven’t seen this gender mix, I think, since the early fifties.”

He also has seen a growth in sales of comics for children, and a resulting increase in material aimed at elementary school and middle school audiences. Among the superstars in this set is cartoonist Raina Telgemeier, whose books have sold in the millions to mainly middle-grade readers. But comic shops are not guaranteed this business, Griepp said. If shops do not work hard to accommodate all audiences, there are plenty of other places to buy the same stuff.

These new readers are in addition to what he calls the “core audience,” a term that evokes the image of a certain type of fan, a white man in his thirties and older. However, the core group is defined more by its buying habits than by age, race, or gender. These fans make weekly or near-weekly visits to the shop, often on Wednesday, which is when new comics go on sale. These are some of the same people who were an untapped audience before shops proliferated in the 1980s. And now they are a tapped audience, relentlessly and ridiculously tapped, as Marvel and DC narrowed their focus in the 1990s with products that enticed a shrinking fan base to spend more money per capita, as opposed to broadening the audience. There are no reliable data available to help define the size of the core audience or see trends in its spending. But store owners told me repeatedly that this audience continues to suffer attrition. Many stores, and the industry as a whole, are growing because new types of customers are coming in to fill the gap.

Griepp got into the comics business while a graduate student at the University of Wisconsin. In 1980, he cofounded Capital City Distribution, which grew from two employees to become the country’s largest wholesaler serving comic shops. He got caught on the wrong end of a massive industry consolidation in 1995 and sold the business to his main competitor. Since then, he has reinvented himself as one of the leading analysts and writers about the comics industry.

“I think the story of comic stores is really the story of community,” he said. “That community is a shared interest and a shared passion for these characters. Not just superheroes. Communities around manga and many other genres and subgenres and creators. It’s just reinforcing community. ‘Oh, yeah, that’s really cool.’ ‘I think that’s really cool too.’”

In Philadelphia, Ariell Johnson has managed to build community in short order. She opened Amalgam Comics & Coffeehouse there in late 2015, with the goal of creating a hub for all types of readers.

“I thought it would be cool to have a place where you could buy your comics and stay there and read them and hang out,” she said. The space is split about 50–50 between a comic shop and a coffee shop.

Johnson, who is in her early thirties, got a flurry of media coverage when she opened because she is one of very few black female comic shop owners in the country. Her success has come from appealing to everyone. Her message, to staff and customers, is that all are welcome.

“I have gone into shops, especially when I was just getting into comics, and I was afraid somebody would question my geek cred,” she said. “You feel scrutinized being the only person who looks like you.”

The challenging part for her has been to learn the business side. She has an abundance of coffee-fueled energy and works sixteen hours most days, but only sometimes does she feel that she is getting on top of things. As generations of store owners could tell her, the key to success is learning how to read a chaotic market and manage risk. It also means controlling costs. Long-term retailers need to either have a reservoir of money to call upon or become masters of these practical issues.

The comics business is unlike almost any other. Consider:

• The country’s comic shops are almost all single-site, independent stores. There are some regional chains, such as Newbury Comics in New England and Graham Crackers Comics in the Chicago area, but nobody with physical locations on a national scale. The closest thing to a national chain was Hastings Entertainment, based in Amarillo, Texas, which had more than 120 stores before closing in 2016 following a bankruptcy filing.3 Hastings stocked new comics and back issues as part of a larger selection of electronics, books, and other media. For veterans of the comics business, Hastings was just the latest in a line of would-be national chains that found comics to be a tricky business.

• The comics industry has almost no verifiable sales data. The figures that do exist are estimates based on orders made by comic shops from the largest comics distributor. There are no data about the number of comics sold to actual customers. So whenever I refer to sales estimates, there needs to be this giant caveat. The lack of data is because the comics industry, with about a billion dollars in sales per year, is too small to attract more independent reporting. And so when I say the industry has about a billion dollars in sales, I don’t really know, although that is the number cited by top analysts.4

• The move toward digital media has not affected comics the way it has other forms of entertainment, at least not yet. Digital comics sales were down in 2015, following several years of growth, according to estimates from ICv2.com.5 Comic shop owners had high anxiety about digital comics a few years ago, especially when publishers began offering material digitally on the same day it was available in stores. But the growth of digital has been slow, and there is little evidence that it is taking away sales from print comics. In interviews with shop owners and readers, I heard over and over that digital comics provide a poor reading experience and that the current tablet hardware is not well suited to comics. A somewhat related issue is online comics piracy. Scans of comics get shared on torrent sites alongside music and video. I have seen no reliable estimate of the effects of piracy on comics sales, and few people in the business list it as a top concern.

The Laughing Ogre has lasted, with the same name and address it’s had since it opened in 1994. All that time, the sign has had a goofy illustration of a portly ogre rubbing his belly and laughing so hard his eyes are closed. The store is in a 1950s-era strip mall in a quiet neighborhood about three miles north of Ohio State University. As you enter, the children’s section is to your left, guarded by a five-foot-high Phoney Bone, the scheming antihero from the best-selling Bone comics. The statue is not something Bickel ordered out of a catalogue. It is one of a kind, loaned by Jeff Smith, the Columbus resident and Bone cartoonist, who had the statue built for a book tour. In the local comics scene, no name is bigger than Smith’s. The Scholastic editions of his work have sold millions of copies. If you haven’t heard of Bone, ask a kid about it.

The children’s section is mostly books, from the wordless Owly by Andy Runton to the kid-friendly versions of DC superheroes by Art Baltazar. Princeless’s first volume is by writer Jeremy Whitley and artist M. Goodwin. The children’s periodical comics are along the front wall, in a spinner rack and a wall rack with copies of Scooby-Do, Steven Universe, and many others.

Beyond the children’s section, the focal point is the left wall, along which recent comics and books are racked. This is a near-overwhelming array of products, with precisely 1,008 slots, most of which are periodical comics. Each week about 150 new titles come in, so there is a constant churn, with old items selling out or being relegated to the back room or the back-issue bins.

“People say, ‘You get paid to read comics,’ but I’m so busy,” Bickel says. “My job is never done.”

Most of the rest of the floor space is taken up by bookcases, holding thousands of titles. The prices start at about $10 and go up to more than $100. There are archival editions of classic newspaper strips, graphic novels, and graphic memoirs, among many others.

As comic shops go, Laughing Ogre is on the large side, with about thirty-five hundred square feet open to the public. It has seven employees, and at least three of them are there most open hours. Annual sales are more than $1 million, which again puts the store on the large side.

To understand the business, a few numbers are helpful. Sales of printed material are split about 55–45 between periodical comics and books. For the periodical comics, sales are split about 90–10 between new material and material that is more than a month old. For books, years-old titles are almost as likely to sell as new ones. One of the top-selling books is Watchmen, a collection of a comic book series that began publication in 1986. A strong seller will move about fifty copies per year, and the store keeps multiple copies on the shelf.

Meanwhile, the store has thousands of books with just one copy each. If, for example, you want to buy Welcome to Alflolol, the fourth volume of Valérian and Laureline, a French sci-fi series, it is there and probably not on the shelf at any other retail outlet in the city. But it may sit there for a year or two waiting for a buyer.

Laughing Ogre is now on its third owner, a businessman who lives in Virginia and also owns two shops there. Even Bickel was gone for a while. After the first sale in 2006, he stayed on as an employee but found he didn’t get along with the new management. He left for five years to sell cars. That job paid better and offered more stability, but he missed the people at the store. He came back in 2011, welcomed as a returning hero by employees and longtime customers.

The store’s most recent big change was in the summer of 2015, when several long-term employees left for other jobs or for school. This left Bickel with only one remaining full-time coworker, Lauren McCallister. She was twenty-two at the time and a recent graduate of the Columbus College of Art and Design. She also does autobiographical comics, which she sells on her website, at shows, and at the store.

During the time I spent at Laughing Ogre, it was the Bickel and McCallister show. They served as manager and assistant manager, respectively, and worked with a group of mostly new hires. McCallister likes to call her boss “Old Man,” as in, “I just sorted that shelf, Old Man.”

(Top) Lauren McCallister and Gib Bickel behind the counter at The Laughing Ogre; (bottom) out front, the sign is the same from when the store opened in 1994.

But when he’s not around, she talks about him like this:

“I think he has magical powers,” she said. “I don’t even know how to describe it. He’s like a master salesman, really. He has a way with every single person who comes through the door. Even like the craziest person, he can deal with them so effortlessly. It’s absolutely mind-boggling. Still to this day, after working with him for three years, I can’t tell you what kind of weird voodoo he’s working.”

The owners and managers of the best shops are a collection small enough that most of them know each other. They have seen some of the best in the business fail. They have failed themselves, or at least come close. Much of this is because of the unique risks of selling comics, a set of dangers that exceed the substantial challenges confronted in running many other types of small businesses.

Almost nothing about this model makes sense if you look at it purely in terms of profit and loss. You are much better off opening a Subway franchise. The best comic shops can mitigate the risk with smart ordering, loyal customers, and a few lucky breaks. But why is the model so intrinsically challenging? How did it get to be this way? That story begins decades ago, and it involves a collection of hippies and geeks and a Brooklyn high school English teacher named Phil Seuling.