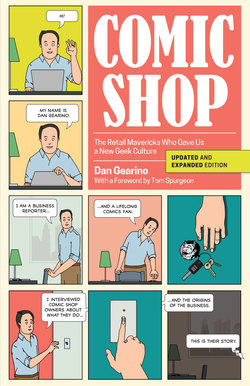

Читать книгу Comic Shop - Dan Gearino - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2

This Bold Guy (1968–73)

THE BOYS were in their early teens in the summer of 1968, a month away from starting high school, and this was an adventure. They got on the train in Manhattan and took it all the way out to Woodside, Queens. They had heard, but did not completely believe, that there was such a thing as a comic book store.

At that time, new comics could be bought in almost every neighborhood at newsstands, drugstores, and candy stores. Old comics could be found in dusty stacks in used bookstores and flea markets. But there were almost no places where a serious fan could look through an organized selection of back issues.

That was the novelty of Victory Thrift Shop in Woodside, and that was why Jim Hanley’s life changed the day he and his friends entered the place. Hanley would grow up to become one of the most successful comics retailers on the East Coast.

“It was the most amazing thing we’d ever seen,” he said. “We went there in the elevated train to the store, and as we get there, there’s a window, a display window, floor-to-ceiling comics. There was Action Comics 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. Superman 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. Marvel Mystery 1, 2, 3, 4, 5.”

There is some debate about where and when the first comics specialty shop opened, often turning on how you define “comic shop.” The store in Woodside, starting in 1961, was one of the first to publicly display comics as collectibles and sell them for more than cover price. The comics were protected with clear plastic bags, another innovation of the store’s owner, a pioneer of comics retail: Robert Bell.

Many fans from the 1960s to the 1980s know the name Robert Bell because of his ads in comics and fanzines, selling his products through mail order. Fewer people know that before the eponymous mail order business, he had the Queens storefront, which he opened when he was just eighteen.

There is a tall-tale quality to what old retailers and fans say about Bell, but I have yet to find one of those stories that doesn’t check out. Yes, Bell hoarded copies of Fantastic Four #1 when it came out in 1961, acquiring them for as little as a dime apiece and then holding onto them as their resale value soared. Yes, he had at least a single copy of every Marvel comic from 1961 to about 1980. Yes, he had a prominent ad on the first Overstreet Comic Book Price Guide and remained a key advertiser in later years as the guide became an industry standard. The stories end with Bell selling his collection in the mid-1980s and vanishing from the comics scene.

“I bought my first property, real estate, when I was thirteen,” said Bell, speaking from his oceanfront condo in Pompano Beach, Florida, where he is semiretired. His success in comics gave him the money to invest in commercial real estate, and that was the focus of his professional life in the thirty years since he stopped selling comics. “I had a vending route with gumball machines. I had mail-order drop shipping for multiple different products. And then, at eighteen, the bookstore.”

The store was a successor to the thrift store that had been run by his parents in a separate part of the neighborhood. He grew up in that store, and, when his parents decided to get out of retail, he took the name of their business, Victory Thrift, and put it on a new location that would be his to run. The name referred to the Allies’ victory in World War II.

At the start, his top-selling items were paperback books, which he bought for one-fourth of cover price and resold for half of cover price. But he could see rising interest in his small selection of comics. New titles, such as Amazing Spider-Man and Fantastic Four, were attracting an older reader and a more devoted fan. He found that he could resell back issues of those comics and others for more than cover price.

To protect the most valuable issues, he cut and folded clear plastic from a dry cleaner and then taped it shut in the back. Finding that some customers wanted to buy these makeshift bags, he decided to mass-produce them. He shopped around for contract manufacturers and selected one that would make him tens of thousands of clear bags. Unlike the dry-cleaner bags, the “Bell bags” were the perfect size for comics.

Comics were about 10 percent of his sales in 1961 and grew to half of his sales near the end of the decade, when he left the storefront and focused on selling comics through mail order. (After he left, his mother took over the space and turned it into more of a thrift shop, buying and selling household items.) He built his comics sales by making connections with suppliers, following leads toward private collections, and advertising on the radio.

He tells the story of a woman who phoned him and said, “I have a box of books and I was on the way to the dump to throw them out. My son said they might be worth some money.” Her collection included the first three issues of Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories and the first issue of Batman, all in near-perfect condition, among many others. He paid her $3,000, which was “a lot of money back then,” Bell said.

The most valuable comics, then and now, were from the early days of superheroes in the 1930s. Among the first publishers of periodical comics was the company that would become DC Comics, which began with New Fun in 1935, an anthology series. Three years later, the company published Action Comics #1, the debut of Superman, and kickstarted the era of the superhero.1

Almost immediately, comic books were a mass medium, sold through grocery stores, candy stores, newsstands, and about anywhere else newspapers could be found. As with almost any printed material, some readers saved the old issues and some retailers resold them, providing a glimmer of a secondary market.

One of the earliest known comics specialty retailers was Harvey T. “Pop” Hollinger in Concordia, Kansas, a small city about a three-hour drive northwest of Topeka. Starting in the late 1930s, he opened a store selling used comics and other items, according to a profile in the 1981 edition of the Overstreet guide. He found that one of the big problems with comics was durability, so he developed modifications that included brown tape and extra staples along the spines. The results, which would horrify collectors seeking “mint” condition, can still be found on the secondary market, often described as Hollinger-rebuilt comics.2

Another early comics retailer was Claude Held in Buffalo, New York, who had a well-stocked comics section in his used bookstore and sold comics through mail order beginning in the 1960s. On the West Coast, one of the important early retailers was Cherokee Books in Los Angeles, which opened in 1949 and by the mid-1960s had a comics section on the second floor.3

In the New York City area, Bell was one of the big players in a small world of comics dealers. His contemporaries included Passaic Books in New Jersey, a giant used bookstore with a comics section, and Howard Rogofsky, who ran a mail-order business out of his home. The dealers knew each other and shopped each others’ inventory, maintaining a polite rivalry.

The early dealers were a mix of adults and teenagers. In Texas, Buddy Saunders began to collect comics in earnest in 1961, when he was in his early teens. “When Fantastic Four #1 came out, I was pretty impressed with it, so I bought two copies, one for my collection, and one I sold a month later. Doubled my money at 25 cents,” Saunders said. “I can make the claim that I am probably the only comics retailer around today that has sold a mint copy of Fantastic Four #1 for a quarter. Probably would have been better then if I had kept it, but I was doubling my money, and impressed with myself.” Today, that comic would sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars.

He was a key player in some of the early fan-produced publications, including Rocket’s Blast Comicollector, which started in 1964. He contributed illustrations, and also placed ads in which he sold his own comics, generating money that he used to buy more comics. More than a decade later, he would found Lone Star Comics in the Dallas area. It would grow into a chain of stores, and exists today as MyComicShop.com, a large online retailer of classic comics.

Most of the early dealers knew of Bell because of his ads and his mail-order business, but his Queens store was not as well known. The store is notable in hindsight because it looked so much like the shops that would follow. He turned out to have near-perfect timing, opening the business right on the cusp of a boom in fan culture and a growing interest in collecting comics.

As Bell sees it, everything changed in 1968. He got a table that year at the Convention of Comic Book Art, held at the Statler Hilton in Manhattan. The event was a leap up from its predecessors in terms of the level of organization and the size of the crowd. “People came in with money in their hands, not their pockets, they were so eager to buy comics,” he said.

This is where Bell’s story crosses over with a much bigger one. The convention had been organized by a high school English teacher from Brooklyn, a tough guy with a goofball smile who would turn out to be the instigator of an explosion of new comic shops. His name was Phil Seuling, and much of today’s retail model, the good and the terrible, can be traced back to what he soon would start.

The New York convention got much bigger in the following year, 1969. At a Saturday luncheon, the guests, a group of mostly young men, turned to look at a camera. A few smiled. The resulting black-and-white photograph is a jolt of nostalgia, showing a time when comics fandom was so small that many of the country’s best-known comics creators, and their fans, could fit into a room and have a meal together.4

Along the back wall are the guests of honor, including the one most likely to have been known to the general public: Hal Foster, creator of the Prince Valiant newspaper strip. He has white hair and dark-rimmed glasses, and is among the oldest people there. To his left is Gil Kane, the artist known for his work on DC’s Green Lantern and The Atom, dapper in a jacket and tie and looking, as he often did, like the coolest professor on campus. Standing by the side wall are some of the Marvel guys, such as the boyish writer and editor Roy Thomas, whose glasses are white from the reflected flash, and his frequent collaborator, artist John Buscema, big and tall with a bushy goatee. In the foreground are tables for the paying guests, mostly young men in jackets and ties.

For Irene Vartanoff, it was the summer between high school and college. In the photo, she is dressed in a serape; she remembers that the room was chilly and that she wished she had brought a coat. To her right sits her younger sister, Ellen; they are some of the only women unaccompanied by a boyfriend or husband. Irene would go on to work on the editorial staff at Marvel and DC, and Ellen would become an artist and arts educator in Washington, D.C. Also at their table are friends they had met through the Illegitimate Sons of Superman, a fan-organized club for young DC readers. Among them are Marv Wolfman, Len Wein, and Dick Giordano, all of whom were already, or would become, prolific comics creators and editors.

“Everybody knew everybody,” Irene said. “We’d all troop out to Tad’s Steakhouse, where you could get dinner for less than $2. We’d talk about comics or James Bond or The Prisoner or Modesty Blaise, a bunch of the things that were related.”

Among the overwhelmingly white crowd, the photo shows three black men: Richard “Grass” Green, a cartoonist from Indiana who was known for his work in fan publications; Arvell Jones, who would go on to draw comics for DC and Marvel; and a man dressed in a suit whom I have not been able to identify.

In all, there are more than one hundred people shown. But I want to draw your attention to someone in the back, next to the guests of honor. He is dressed in a jacket and tie and has slicked-back hair. He has a blank expression, choosing not to show his goofy smile. This is Phil Seuling.

He had organized the Saturday luncheon, a small part of his convention, a better follow-up to the convention he had done the year before. A few years later, he would help develop a new way of distributing comics. He was, in many ways, the father of modern comics retail.

“He was this bold guy,” said Jim Hanley, who went to his first Seuling convention as a teenager the following year. “He didn’t walk into the room, he stormed into the room. He jumped onto the stage and grabbed the microphone and captivated the audience instantly. He had spent probably ten years at that point teaching school, so he was used to being in front of an audience every day, and he was good at it. He always had the loudest voice in the room, and he knew us.”

The “us” part was important. Hanley and the other mostly younger fans at the conventions saw themselves as a tribe, a group whose loyalty was hardened by the outside perception that comics were a kids’ medium. “I was the reticent kid, which was pretty common among comics fans,” he said.

Seuling had a way of welcoming strangers. For the 1968 convention, a young comics fan from San Jose, California, drove across the country to stay with Seuling and his family and serve as an assistant at the show. That was Michelle Nolan, who was twenty, and would go on to be prolific writer and editor on comics history.

“I stayed in his comic book room,” Nolan said. “He had a nice apartment in Brooklyn near Coney Island. You could see the Wonder Wheel and Cyclone from his window.”

Nolan would turn out to be a crucial connection. Back in California, she was part of a close-knit group of comics fans. Among them was a high school kid named Francis Plant, who went by his nickname, Bud. He would go on to co-own what may have been the first comic shop chain, Comics & Comix, and would have a separate business selling comics and books through the mail.

(Top) Phil Seuling on stage at the 1971 Comic Art Convention, held at the Statler Hilton in Manhattan; (bottom) outside the ballroom was the dealers’ room, where dealers set up to sell to fans and collectors. Credit: Mike Zeck.

For the 1970 convention, Nolan, Plant, and others loaded up a van and made the drive east to stay with Seuling and help at his convention. Other than Nolan, who had worked at the two previous shows, Seuling didn’t know any of them.

The van rolled into Brooklyn at about 11:30 p.m. The visitors found parking and then arrived at Seuling’s apartment door. With some reluctance, considering the hour, they knocked. The door swung open, and there was Seuling, dressed only in a pair of white briefs.

“It’s New York and it’s July and it’s hot as shit,” Plant said. Instead of being upset or embarrassed, Seuling waved everyone in and showed them to his living room, where they would sleep.

Plant was meeting a man who would become his most important business mentor and an even better friend.

“When there was a group of people, he would always be the center of attention,” Plant said. “He told the stories. He flirted with the cute waitresses. He always picked up the dinner tabs. He was older than us, but he was a high school teacher, so he was used to dealing with lots of kids.”

And yet there was another side to Seuling. He could go from a smiling pal to a red-faced fury. For out-of-towners, he fit the image of a tough New Yorker, tall and broad-shouldered, with a Brooklyn accent and a short fuse. “Phil was a streetwise guy,” Plant said. “He was from Brooklyn, and they grow up a lot faster than little neophytes from California. We went back there and our eyes were opened. It was just a different world.”

The Bay Area had its own burgeoning comics scene. Despite his youth, Plant had been a part of it for years. He grew up reading Disney comics and moved on to DC and Marvel. In his early teens, he shopped at Twice Read Books, a used bookstore in downtown San Jose. There was a stack of old comics by the door for a nickel each. Then one day he saw another customer ask to see the dollar comics.

“I was aghast. I never heard of a dollar comic,” he said.

From behind the counter the store clerk pulled out a box of comics from the 1940s and early 1950s. Plant was fascinated by the idea that comics had a rich history of characters he had never seen. He bought Thrills of Tomorrow #19, cover dated February 1955 and published by Harvey Comics, which was itself a reprint of a Harvey comic from 1946 called Stuntman, written and drawn by the cocreators of Captain America, Jack Kirby and Joe Simon.

From his visits to the dollar box, he met other fans of old comics, and they became friends, a mix of adults and teens that included Nolan. “If anything, I was probably very shy in high school,” Plant said. “I just wasn’t one of the hip guys. I had glasses. I had acne. I wasn’t that good at sports.” With comics, he felt like he was part of something.

In March 1968, when he was sixteen, several of the group pooled their comics, books, and cash and opened a small store, Seven Sons Comic Shop. Less than a year later, the partners sold the business to one of the co-owners. Some of the same people, including Plant, soon opened an even smaller store in San Jose called Comic World. It lasted about a year before the co-owners moved on to other things. For Plant, this meant enrolling at San Jose State. He would study business, having already been a co-owner of two businesses.

Meanwhile, an hour’s drive north, Gary Arlington opened San Francisco Comic Book Co. in that city’s Mission District. He was starting in April 1968, a few weeks after Seven Sons, although the people involved did not know of each other’s stores at the time. His business became closely associated with underground comics, the irreverent and boundary-pushing publications that nobody would confuse with DC or Marvel. One of the key underground titles, Zap Comix, was published in San Francisco that same year, with stories by Robert Crumb, Spain Rodriguez, and others. The undergrounds developed their own retail networks of head shops and record stores as opposed to pharmacies and candy stores.5

“A buddy of mine turned me on to Zap and said, ‘You’ve got to read this underground comic,’ and I read it and I couldn’t really understand quite what was going on,” Plant said. “I was not smoking dope. I didn’t have a kind of stoned attitude. I was a high school kid reading Spider-Man. The undergrounds sort of blossomed from there over the next two or three years, and I sort of grew into that.”

All of this was part of the context when Plant and friends got in their van in 1970 to go to New York. The Bay Area guys were bringing their own bustling comics culture. As they made connections with Seuling, they would help create a national framework for comic shops to do business.

Some of the people and places of the Bay Area comics scene. (Top) A young Bud Plant in the 1970s; (middle) one of the only photos in existence of Comic World, the San Jose shop briefly co-owned by Plant and several others, including Dick Swan, pictured, who was fifteen at the time; (bottom) Gary Arlington at his store, San Francisco Comic Book Co. Credits: Clay Geerdes, except for Comic World, which is courtesy of Dick Swan.

Seuling’s convention took off at a time when comics had begun to attract a broader audience that included older readers. The new fans didn’t want to miss an issue. “There were more creators beginning to do work that presumed the audience was older or more intelligent,” said Paul Levitz, who was a young fan in New York and would go on to be a writer and executive at DC Comics. “It’s really in the early sixties when you get to Stan [Lee]’s work at Marvel, particularly Julie Schwartz’s work on the superhero revival at DC, that it begins to be inviting to an older, brighter audience.” He published his first fanzine in the late 1960s and became one of the leading writers in the fan community, years before he worked at DC.

At the same time, many readers found it difficult to obtain the comics they wanted. The major publishers sold through a network of independent distributors. The distributors were entrenched businesses that had hard-earned territories of newsstands, grocery stores, and drugstores. They sold a wide array of printed material, of which comics were a small and not particularly profitable part.

“There was no way for me to get a comic if I missed it on the stands,” said Irene Vartanoff. She was part of a generation of fans who developed their own system for finding back issues, trading and selling comics through the mail with other fans. Some comics publishers helped facilitate this by printing letters from fans who wanted to buy or trade specific issues. Vartanoff became known in the fan community for how often her letters appeared in comics.

Fans in this new generation were willing to pay more than cover price to get an issue they missed. In turn, the idea of comics as collectibles began to gain currency, a concept that got a boost from news coverage of rare comics selling for hundreds of dollars.

In this environment, a time of rising interest in comics but an unreliable distribution system, Seuling came into prominence. He was a Brooklyn guy, born and raised. He got drafted during the Korean War, and did all of his service in the United States, mostly in Texas. From there, he went to City College in New York.6

He met a woman named Carole in an introduction to geology class, and they hit it off. They got married in 1954, while both were still students. “City College was a place where people let it all hang out,” said Carole Seuling, who is now retired and living in Connecticut. The campus had a bustling political scene, an early glimmering of the protest movements that would later arrive on campuses across the country.

Phil and Carole both studied to be English teachers. After college, they got jobs in the city’s public school system and settled in Bensonhurst in Brooklyn. They had two daughters, Gwen and Heather. Contrary to what Phil would later say in interviews, he was not a regular comics reader during his early adult years. His interest in comics was rekindled in the early 1960s when he and a friend, Doug Berman, came upon a stack of Golden Age comics for sale in a thrift shop, Carole said.

“He and his friend Doug decided there’s money to be made here,” she said. “They started scouring these junk stores and bought up all the comics they could find.”

The couple’s apartment became a warehouse for the growing collection. One memorable purchase was in 1963, which Carole remembers because it was the same day as President Kennedy’s funeral. “They came back with the mother lode,” she said. “I mean, there were six copies of Life #1 and three copies of Action #1. Three. And then that was the tip of the iceberg. . . . People didn’t really know what they were selling. They wised up in the seventies and started asking for more money.”

While Phil depended on teaching for his main income, he developed a bustling side business in comics. He bought and sold through ads in early fanzines. At some of the very first comics conventions in the mid-1960s, he was among the few dozen people there. He was part-owner of After Hours Bookstore in Brooklyn, which sold used books and comics.7 Then, in 1968, he took over as lead organizer for an existing New York convention. The event, held on Fourth of July weekend, grew to become a destination for comics fans, dealers, and professionals from across the country.

The conventions mainly dealt with the sales of old comics, but Phil saw an opportunity in selling new comics. He later spoke about this in an interview with the cartoonist Will Eisner.8

“A friend of mine in the sixties owned a little candy store, so I got an inside view of distribution there,” Seuling said. “Tony Fibbio was his name, lovely guy, passed away. He collected and he knew what kids wanted, but he couldn’t get the books he wanted. The distributors would not give him the titles.”

A store could not order specific numbers of each title and did not know when the titles would arrive. Instead, retailers received an assortment selected by the distributor, sometimes bound in ties that damaged the comics. One of the fundamentals of this system was returnability. If comics, magazines, or other printed material didn’t sell, the distributor would pick them up and return them for a credit. So, while the service was often lousy for comics fans, the financial risk was low for the newsstands and pharmacies that sold them.

“I said and I repeated it: ‘There is another way of doing this,’” Seuling said to Eisner. “You could sell them directly and not even take returns. That was considered so far out, so ludicrous, that it was greeted with laughter, a friendly pat on the back.”

The people laughing were the comics publishers. Seuling was in a unique position to propose his idea because the publishers knew him from his conventions. He could connect on a personal level with people such as Carmine Infantino, DC’s top editor and a longtime comics artist, because they were both New Yorkers and they had a love for the medium and a respect for its history. Despite those connections, Seuling could not immediately persuade the executives to make major changes to their distribution system. But he was persistent, and he was going to keep making his case.

In the convention’s early years, Carole Seuling was there as a confidante and counterpoint. Many of the comics fans and creators who were part of the early shows were friends with both of them. In one photo from the era, Phil is dressed as Captain Marvel, with a sewed-on lightning bolt across the chest, and Carole is next to him dressed as Mary Marvel. They both look clean-cut, him with a smile and her with a grin.

But the couple was growing apart. She didn’t go into specifics other than to say that he had become more interested in the hippie culture of the time. “I changed. He changed,” she said. “He never got over Woodstock, the fact that he didn’t get there,” she said. “He didn’t know a damn thing about it until he saw it on TV. He couldn’t believe he hadn’t heard about it and didn’t get there.” They separated in 1971 and later divorced.

Phil, who was still a full-time teacher, had to adapt to the financial strain of paying child support.9 Their daughters would split time between the parents, who now had two apartments in Brooklyn. The younger daughter, Heather, whose last name is now Antonelli, was nine when her parents separated. “We knew we were safe and we were going to see both of them and it was not the end of the world,” she said. “They did their best to make it palatable and acceptable.”

Carole kept the name Seuling, which she says was to not confuse her children. “He and I remained friendly but not friends,” she said. “His family never stopped considering me part of the family.”

Phil’s conventions remained strong, with the big one each July, and later monthly conventions at smaller venues. He supported all types of comics, and he allowed underground material to be sold at his shows. Among them was the infamous Zap Comix #4, which had a story by Robert Crumb called “Joe Blow.” In a cartoony style reminiscent of children’s comics, the story shows a smiling suburban family whose evening descends into an incestuous orgy. The story became a flashpoint with church-sponsored groups, used in campaigns to ban comics.10

On March 11, 1973, the campaign hit Seuling’s monthly show. Police officers entered and asked to speak with the organizers. When they met Seuling, he was told, “This is an arrest.” He and three of his workers were handcuffed and taken in a squad car to jail. They stood accused of selling indecent material to a minor, the kind of charges that Seuling knew could cost him his job and his reputation. He stood to lose everything.

Strong Silent Type

Mike Zeck was a star artist for Marvel, known for his dynamic covers and his knack for action sequences. He drew Captain America, The Punisher, and “Kraven’s Last Hunt,” a critically lauded Spider-Man story, among many others. Before he broke into the business, he was a young fan in Florida with a fondness for Black Bolt, the Marvel character who is often silent because his voice releases a devastating shockwave. Here, Zeck tells the story:

I was a rabid comics fan throughout my childhood and always dreamed of being a comics artist someday. In 1970, after art college, I went home to Hollywood, Florida, and I started connecting with the fan community there. I was well aware of Phil Seuling’s Fourth of July shows in New York City and decided that 1971 would be the year I would realize the dream of attending one.

I started saving money to buy some titles I needed to fill in my Marvel collection. Most of my time, though, was spent preparing for the show’s costume contest. I was inspired by Neal Adams’s version of Black Bolt, so that was my character choice. Never doing things in half measures, I mail-ordered stretch satin material, had a tailor help with the basic bodysuit, sewed all details of the costume myself (including the collapsible underarm glider wings), and shopped for or made all accessories. Even with my perfectionism, I liked the end product, so I knew I wouldn’t be embarrassed in New York.

The drive from South Florida to Manhattan was a long one, but I was too excited to be tired. When I got to the show, it lived up to its billing. I saw many of the artists, writers, and editors I idolized as a fan. This went beyond the advertised guests because so many comics professionals lived in the city and attended the convention. One highlight: Frank Frazetta set up a gallery room at the hotel and let fans come in and browse his paintings.

As awesome as all that was, the best was yet to come, the costume contest. I suited up and made my way to the contestant holding room next to the auditorium. When I walked in, all faces collectively sank and there were mutterings about a professional showing up. I took that as a good sign.

I walked on stage to a roaring crowd. News crews were there as well. The judges, Jim Steranko, Gardner Fox, and Kirk Alyn, picked me as the winner. No doubt the best moment was accepting the first-place award and hearing the crowd start yelling “Speech!” “Speech!” I stayed in character and remained tight-lipped, just like the Black Bolt would do.

I didn’t know much about Phil Seuling at that time other than he was a fan, a comics dealer, and he ran the biggest comics convention in the land. That made him something of a celebrity in my eyes. I had the chance to meet him and speak with him during and around the costume contest, and he was incredibly nice. I got the impression he was enjoying the show as much or more than the other attendees. He was always on stage or present, whether it be panel discussions, auctions, awards, contests, or dinners. Almost as if he was running the show entirely by himself.

While at the convention, Zeck took photos that now stand as some of the best records of the event. The photos in this section are all by him.

Mike Zeck in the homemade outfit that won him first place at the convention’s costume contest. Black Bolt © Marvel Entertainment. Credit: Mike Zeck.

On the sales floor, a fan looks through old comics stored in a box labeled for egg noodles. Credit: Mike Zeck.

Some of the comics creators who were stars of the show: (left to right) Frank Frazetta, known for his fantasy paperback covers and paintings; Harvey Kurtzman, the cartoonist and editor who helped launch Mad; and Gil Kane, a star artist best known for his work on Green Lantern. Credit: Mike Zeck.

Phil Seuling auctions a page of original art from DC’s Showcase #29, “The Last Dive of the Sea Devils.” Credit: Mike Zeck.