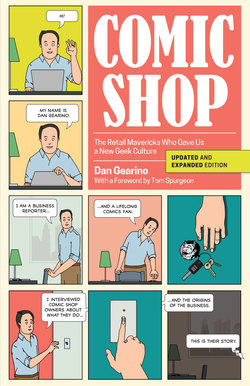

Читать книгу Comic Shop - Dan Gearino - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление3

Nonreturnable (1973–80)

“ON MARCH 11, 1973, at 4 p.m., I was told by a tall man with a firm angry voice that ‘this is an arrest.’ Then, within a few bewildered minutes, I was taken away from my friends and my business, put into handcuffs and led away to a waiting patrol car.”

So begins a guest editorial written by Phil Seuling in the June 1973 issue of Vampirella, a magazine-sized comic from Warren Publishing.1 Jim Warren, the publisher, said in an introductory note that he had provided the space for his friend, “one of the most respected dealers in the comics market.”

Much of the comics industry stood to lose from this wave of censorship that had hit Seuling, including outfits such as Warren, whose publications were aimed at an older audience and had more sex and violence than a major publisher would ever put in a superhero comic.

Vampirella was pure pulp. In the lead story that month, the scantily clad title character was drugged by a band of street toughs. She got her revenge with a blood-sucking rampage. The letter column was dominated by a debate among readers about whether Vampi, as she was nicknamed, had an unrealistically large cup size. The editorial was an oddly sober counterpoint.

“I can’t easily express the feelings of being led in handcuffs from the show. Or being questioned, fingerprinted, mugged [photographed], placed in a cell overnight, and left till morning. Or knowing that the animal pens procedure was being inflicted on two teenage girls who were working at my tables and were miserably frightened at this cold, heavy treatment.”

One of those teenage girls was Jonni Levas, age seventeen. She had met Seuling when he was her teacher. At some point before the arrest, she and Seuling became a couple, something she said she instigated. “Of course people raised eyebrows,” she said. “After a while, when people saw we were still together, they stopped raising their eyebrows.” Other people in their circle, including Bud Plant, remember her as hip but not a hippie. The day of the arrest was one of the worst of her life.

“All I knew of New York City detectives was Kojak,” she said, speaking from Palmyra, New Jersey, where she now lives. “We were taken away in handcuffs and we were told it was a felony and that meant they could shoot us if we ran away.”

Seuling, Levas, and the others spent more than twenty hours in separate cells without food or water before they were allowed to see a lawyer. During that time, news of the arrest appeared in the local media, Seuling said in the editorial. The reports named a church-sponsored group that had a campaign against so-called obscene comics, which he saw as evidence that the arrest and the immediate coverage were all a publicity stunt at his expense.

Stunt or not, he faced life-changing consequences. His employer, the New York public school system, forced him to leave the classroom and report for nonteaching duty while school officials investigated the charges. Instead of going to work, he went to a place nicknamed the “rubber room,” where teachers who had run afoul of the system sat at desks and waited out the days while their cases worked through the system.

A few months after the arrest, a court dropped the charges. Seuling agreed to refrain from selling potentially obscene material. He continued with his monthly shows and his big show in July. “Since then, only the tamest titles have appeared at the Second Sunday shows,” said a report that summer in The Buyer’s Guide for Comic Fandom. “Unfortunately, that leaves out much of Richard Corben’s work and many of the better-written titles, like Skull.”2

Even with the charges dropped, Seuling’s bosses would not let him return to the classroom. He was on an indefinite hiatus.

As this was happening, the comics industry had gone into one of its periodic downturns. Sales at newsstands had plummeted. The retail world was shifting away from independent grocers and pharmacies and toward large chains. While many older retailers stocked comics out of habit, the chains were deliberate in deciding how to allocate rack space. In this type of assessment, comics did not fare well. They had low cover prices, about 20 cents each, which meant the retailer stood to make only a few pennies of profit from each sale.3

Another factor was fraud by some of the news distributors. Since comics and other printed materials were sold on a returnable basis, the distributors could return unsold items for credit toward other purchases. At one time, returns meant sending whole comics, or at least the covers, to receive credit. This evolved into a system in which publishers allowed distributors to file an affidavit saying that a list of items was unsold and had been destroyed. Some distributors would sell the books out the back door, often to comics dealers, and still report them as unsold.

“You’d send them ten thousand copies and they would send you an affidavit that said they only sold two thousand,” said Jim Shooter, who started writing for DC Comics as a teenager in the mid-1960s and went on to be editor in chief of Marvel from 1978 to 1987. “Well, maybe they sold four thousand. With the affidavits, they only had to pay for two thousand.”

He remembers that one particularly audacious news distributor sent an affidavit claiming that the number of unsold copies was greater than the number of copies that had been shipped. Instead of rejecting it out of hand, Marvel trod carefully. News distributors were gatekeepers to doing business in their territories, and some of the companies had reputations for ties to organized crime. Shooter remembers that Marvel’s circulation managers warned that specific distributors were not to be trifled with.

In 1973, the news distributors were the only option for getting comics into the hands of customers. Sales were way down, which probably was tied to a decline in consumer interest, exacerbated by fraud by news vendors. Now Seuling found an audience that was more receptive to his idea of selling directly to specialty shops.

In August, he was at the San Diego Comic-Con, where he scheduled a breakfast with Sol Harrison, a vice president at DC. The San Diego convention would grow to become the largest in the world, but at that time it was smaller than Seuling’s annual event in New York. Also at the breakfast was Levas, whose role was business partner in addition to girlfriend.

Seuling and Harrison knew each other because of the New York show. Harrison “was an older gentlemen, a dapper New York gentleman,” Levas said. “He was funny and kind.”

By the end of the meal, they had a handshake deal. They agreed to meet soon in New York to set the details. In the months to follow, Seuling would make similar agreements with Marvel, Archie, and Warren, which were other major publishers. In that moment, however, the new venture didn’t seem big, Levas said. It was one of several side businesses involving comics, along with the conventions and mail-order sales of old comics.

“Did he think it was something monumental? No,” Levas said. “But it turned out to be monumental.”

Here was the new business model: retailers could order comics from Seuling and get shipments straight from the printing plants, bypassing the old-line distributors. This meant the comics would arrive sooner than at other outlets, and in precise quantities.

The system would come to be called the “direct market,” because comics were skipping the middleman and going directly to the retailers. This was possible because the major publishers did their printing with the same company in Sparta, Illinois. The printer would collate the orders and ship them to Seuling’s customers, just as they did for hundreds of news distributors.

The new system had benefits and risks. Orders from Seuling had a greater wholesale discount than those from the old distributors, but also were nonreturnable. This meant that if a store ordered twenty-five copies of Superman and sold only five, it was stuck with the surplus. Also, Seuling required up-front payment with each order, even though the comics didn’t ship until months later.

At that time, there were few retail outlets that could be called comic shops. If you broadly define “comic shop” to include used bookstores with large comics sections, there were fewer than two hundred stores nationwide, according to retailers from that time.4 Within this total were only a few dozen of the kind of comics specialty stores that would come to dominate the industry.

Seuling was able to get orders from many of the store owners because the business model made sense to them, and because he had built up trust from his years in fandom and his conventions.5 His new idea was an immediate success, exceeding his expectations.6 The new venture was later incorporated as Sea Gate Distributors.

Within months of Seuling starting the distribution business, Marvel made a similar deal with another vendor, Donahoe Brothers, in Ann Arbor, Michigan.7 Other distributors would soon open, such as Pacific Comics in San Diego and Irjax Enterprises in Maryland, but they mostly sold comics-related goods and did not have contracts with the major publishers.8

Seuling was king, with the best retailer accounts and the best terms with the companies that produced comics. But those other players, at least the ones that lasted more than a year or two, would have important roles near the end of the decade, when the industry got much bigger and more complicated.

Of all the non-Seuling upstarts, Donahoe Brothers, also known as Comic Center Enterprises and by its nickname, Donahoe Brudders, was notable for the swiftness and audacity of its rise and its equally rapid fall. The man in charge was Tim Donahoe, a smooth talker in his midtwenties.

“Some people distrusted him on sight, including my wife,” said Jim Friel, who had built a business selling publishers’ new comics at conventions, and also drew his own comics. “I just thought of him as a smooth guy who was probably okay. Her perception was more accurate than mine.”

Friel was one of the first people hired by Donahoe Brothers who was not a member of the family. He had grown up in North Carolina and came north to attend Michigan State University. His employment with Donahoe Brothers would turn out to be a small blemish on what would become a long and successful run working for some of the key players in comics retail.

Donahoe Brothers’ ambition was to be a regional comics distributor serving Michigan, Ohio, and the other Great Lakes states. The company signed up a roster of accounts that included longtime bookstores and newly opened comic shops. The retailers could order precise quantities of specific comics on a nonreturnable basis and receive a larger discount than what was offered by news distributors on a returnable basis. It was almost the same as Seuling’s model.

The first shipment was in early 1974. Friel remembers that one of the comics from the first batch was Marvel Super Stars #1, which had a cover date of May.9 Comics publishers typically set the cover date three months ahead, which means that first shipment likely was in February. Soon after, Donahoe Brothers added DC Comics to their offerings, along with other publishers.

About a year after that first shipment, Friel was by himself in the warehouse when the phone rang. It was Carmine Infantino, DC’s president and one of the most popular artists in the business, known for Batman and The Flash. He asked to speak with Tim, who was not there.

“Well, you tell that son of a bitch I’m going to come out there and padlock his fucking warehouse,” Infantino said, according to Friel.

Donahoe Brothers had been receiving merchandise and reselling it, without paying the publishers. Friel had suspected that something was amiss, but did not know the scale of it.

“It was a deal Carmine had made personally, and he felt betrayed personally,” Friel said. “It feels terrible to have one of your artistic idols yelling at you like that. It was Carmine Infantino, for God’s sake.”

Later that day, Friel confronted Tim Donahoe, who matter-of-factly confirmed that many bills had gone unpaid. Within a month or so, the company ceased operation, a little more than a year after it had gotten into comics.

Donahoe Brothers was more than just a curiosity. It turned out to be the first in a succession of midwestern distributors that helped develop comic shops in that part of the country while Seuling’s business was in its infancy. Donahoe Brothers’ fall was followed by the rise of Big Rapids Distribution of Detroit, whose demise in 1980 was followed by the rise of Capital City Distribution of Madison, Wisconsin. These were some of the first few steps that would lead to explosive growth in the number of comic shops, along with turf wars between distributors.10

By early 1974, Seuling and Levas were living together in a house in Sea Gate, a gated community on the western end of Coney Island. From there, they ran the comics distribution business, planned the conventions, and presided over a gathering place for comics professionals and fans.

Jonni Levas during a 1978 trip to London with Phil Seuling, who is seated to the left. Courtesy of Jonni Levas.

After his arrest, Seuling never returned to the classroom. He did non-teaching duties for a few months and then applied for early retirement. He likely could have been reinstated as a teacher, because the criminal charges had been dropped, but he didn’t bother, Levas said. He was ready to move on to something else.

Several people told me that there was a kind of cause and effect with Seuling’s arrest and the founding of the distribution business. In other words, if not for the arrest, Seuling would have kept teaching and not been able to devote himself full-time to comics. Based on interviews with some of the other people closest to Seuling, however, this doesn’t seem to be true. When I asked Levas if Seuling wanted to continue teaching, she said, “No way.” He loved teaching, but he loved comics more.

“And he was always teaching, even if he wasn’t in an actual classroom,” she said. “He would teach whatever silly thing there might be. He would teach what Italian food you should eat, or what movie you should see, or why you should like the Mets more than the Yankees.”

Heather Antonelli, Seuling’s younger daughter, agrees that her father wanted to leave teaching and was not pushed. She was with him the day he went to the administrative offices to file paperwork to leave his job.

“The lady who was processing the paperwork was like, ‘Are you kidding me, because you only have like a year and ten months left to get the pension?’ And he was like, ‘I can’t. I can’t come away from what I’m doing,’” Antonelli said.

Unlike most new businesses, the venture that would become Sea Gate had no cash before its first orders. Seuling and Levas worked for no income. Their operating money came from retailers’ prepayments, most of which was used for prepayments to the comics publishers. There was no credit for anyone.

“It’s insane to think this could work,” Levas said. “I’m amazed we were able to pull this off, with no capital.”

The first accounts included some established and reliable retailers, such as Collectors Book Store in Los Angeles. Among the newer stores was Comics & Comix in Berkeley, California, co-owned by Bud Plant, which would go on to become one of the first, if not the first, comic shop chain, with other locations in Northern California.

Other new stores soon followed. In 1974, Chuck Rozanski used his savings to open a comic shop in the back room of Lois Newman Books, a science fiction bookstore in Boulder, Colorado. He was nineteen and had been buying and selling old comics for years at conventions. The shop was in a basement room with a single lightbulb hanging from the ceiling. He spent most of his $800 budget on a counter and new lights. Mile High Comics was in business.

“The original shop had to be diversified because in those days you were buying new comics for 14 cents and selling them for 20 cents, so you were making a whopping 6 cents per comic book,” he said. “It’s very hard to pay rent or utilities with 6 cents, no matter how much volume you’re doing.”

His big-ticket items were posters by fantasy artists such as Frank Frazetta. He also sold Playboy and Penthouse, and had a selection of bongs and other drug paraphernalia. He had short hair because he had just been in Reserve Officers’ Training Corps in college. His ponytail, the one he would have for decades, braided down to the small of his back, was still in his future.

Seuling’s distribution business had started by the time Mile High opened, but Rozanski got his comics from a local news distributor. Rozanski had worked out a deal with the distributor to get new comics a few days earlier than most other outlets in Boulder. “Instantaneously, every collector in town came to me to get their books,” he said. “It was awesome.”

For small shops, it often didn’t make much sense to do business with Seuling. He required up-front payment for orders of comics that would not be delivered for two months. He also set minimum order limits, meaning shops could not order just one or two copies of low-selling titles. In fairness to Seuling, many of these conditions had been imposed on him by the publishers. Rozanski would come to see Seuling’s rules as an impediment to growth for the industry. “I loved Phil, but Phil could have his head up his ass for no reason,” he said.

But first Rozanski had to learn to run a business and deal with the public. “I was very obnoxious, kind of like a chipmunk on speed,” he said. “I was so enthusiastic and I couldn’t understand why other people didn’t instantly share my enthusiasm. It took me a while to moderate my own enthusiasm. I was also extremely dismissive of other people if they didn’t agree with me. I was kind of an obnoxious little peckerhead. That’s the God’s honest truth.”

A year after he opened, he met the woman he would marry—she’d gotten a job in the adjacent bookstore. He mellowed. Chuck and Nanette Rozanski would soon move Mile High out of the coal closet, and would go on to have a chain of stores that extended down into Denver. The more experience he got, the more he could see the shortcomings of Seuling’s model. Things needed to change, he thought.

Sea Gate was growing about as fast as Seuling and Levas could handle, but it and its customers remained less than 10 percent of sales by major publishers. Shops continued to open, and existing ones grew. In 1977, there were about two hundred comics specialty shops in the United States, a figure that excluded used bookstores that did not sell new comics, according to Melchior Thompson, an economist who studied the market as a consultant for Marvel. Seuling was the den leader for a small industry that was about to get much bigger.

Meanwhile, Seuling maintained his convention business. In 1977 and 1978, he relocated his July show to Philadelphia, before a return to New York. To publicize the 1977 show, he got a booking to appear on The Mike Douglas Show, a nationally syndicated daytime talk show that was filmed in Philadelphia. The cohost was Jamie Farr, the actor who played Corporal Max Klinger on M*A*S*H. The other guests included General William Westmoreland, who had commanded the U.S. forces in Vietnam; and Fabian, the singer, actor, and former teen idol.

“A grown man with a handful of comic books,” said the host, Douglas. He had just introduced Seuling in what was likely the latter’s only national television appearance. There Seuling sat, with bushy sideburns and a stack of vintage comics in his lap. His plastic-rim glasses looked a few sizes too small.

“I didn’t know you were my mother,” Seuling replied, smile in place, his accent turning the last word into “mutha.”

Douglas asked how this comics habit got started.

“I read thousands of them as a kid,” Seuling said. “The interest never died. It’s a love. It’s something that you just can’t do unless you really love it, unless you’re devoted to it.”

Douglas told the audience that Seuling had brought along a superhero. Then out from behind a curtain came a woman dressed in a chain-mail bikini with a prop sword, in the character of Red Sonja. She walked up to Farr and pointed the tip of the sword at his face.

“No nose jobs,” the actor said, laughing. He was known for his oversized schnozz. Seuling was laughing uproariously.

The whole scene epitomizes the late 1970s almost to the point of parody. But the biggest shock for a present-day viewer is the woman playing Red Sonja, not because of the costume, which she wore with aplomb, but because of what she later would do.

Her name was Wendy Pini. She had been performing at comic conventions and other events as Red Sonja for about two years, doing a stage show in which a well-known comics artist, Frank Thorne, played a wizard.

Fewer people knew that Pini wrote and drew comics of her own. She and her husband Richard had created a fantasy story called Elfquest, and they were about to start self-publishing it. Unlike Marvel, DC, and other major publishers, the Pinis did not operate on a scale large enough to get their product into grocery stores and drugstores. They would depend on alternative channels, such as the burgeoning network of comic shops. In turn, comics such as Elfquest would help define the shops as places where fans could find things that were not available through mainstream sources. Elfquest was one of the first big commercial successes of the early comic shop era, inspiring many imitators.

As the show began to cut to commercial, Farr said about Pini, “Now that’s a superhero.”

“The audience loved it,” she said. “But we heard later on that Mike Douglas was quite upset by my racy costume, which didn’t fit in with the tone of his show. C’est la vie.”

Westmoreland was no longer on the set when she made her appearance, but the two did meet backstage. When she arrived, the military man noted her battle armor and said, “I didn’t know we were still at war.”

The first Elfquest story appeared in early 1978 in Fantasy Quarterly #1, published by IPS, a new company controlled in part by Tim Donahoe, the Michigan businessman who had already tried and failed at comics distribution. The Pinis, who felt burned by the poor production values and by some of the business practices of Donahoe, decided to become their own publisher.

The first self-published issue was Elfquest #2, released later in 1978 with a print run of twenty thousand copies. The Pinis called their company WaRP Graphics (WaRP stood for Wendy and Richard Pini). To pay the printing bill, Richard Pini borrowed about $2,000 from his parents.

Self-publishing would have been a highly risky venture if not for the help of Phil Seuling and his network of friends and customers. He knew the Pinis and wanted to support their work. Seuling and Bud Plant pooled their resources to buy the entire print run of twenty thousand copies. They would sell Elfquest through their respective distribution businesses.

“What both Bud and Phil saw, I think, was a new kind of ground-level comic storytelling, heavily influenced by Japanese manga, that had not been seen before,” Wendy Pini said. “They trusted me and my ability to deliver because of my prior experience as an illustrator. And I think, after they sold out the first ten-thousand-copy run of the first issue in under a couple of months, they realized these weird, elfin characters could appeal and catch on. Also we did cliffhangers very well.”

Seuling and Plant sold every copy, giving the Pinis confidence to continue the work. “That took all the pressure off of us,” Richard Pini said. “It was bing, bang, boom.”

There is little doubt that Phil Seuling saw himself as the hero of his story. So who was his archenemy? There are many candidates, but my vote goes to a pugnacious young man named Hal Shuster. As of 1978, Seuling was the biggest player in comics distribution, with the top accounts and the best terms from publishers. Shuster had a small business in Maryland, distributing comics and other material for his family-owned company, Irjax Enterprises.

Irjax had been started in 1973 by Irwin Shuster and his sons Jack and Hal. The name was combination of Irwin and Jack. Although he wasn’t in the name, Hal gave the impression that he ran things. The business was set up to act as a wholesaler of comics and related materials to comic shops. It also was a publisher of magazines about geeky interests, such as Star Trek fandom.11

“I never really felt comfortable talking to him,” said Mike Friedrich, who was on staff at Marvel, serving as the first sales director for the comic shop market from 1980 to 1982. He describes Shuster as an in-your-face kind of guy, with a wardrobe that favored white shirts and thin black ties.

“He was intelligent and confident, but arguably, in my view, overconfident. He was kind of driven by the idea that he was smarter than everybody else and had realized things that the rest of the business had not realized. And, given that he had proven himself to be litigious, I was very careful around him.”

Before coming to Marvel’s sales department, Friedrich was a writer for Marvel and DC and publisher of a comics anthology called Star*Reach. Although barely thirty years old, he had been around the business long enough not to be impressed by Shuster.

Irjax grew from its base in Rockville, Maryland, in the Washington, D.C., suburbs. It wanted to be the dominant wholesaler in the state and neighboring states, and then build from there. This put the company on a collision course with Phil Seuling and Sea Gate. Seuling had started with a few accounts in places such as New York, Buffalo, and the Bay Area. By 1977, he had worked out many of his own organizational problems and was in an expansion mode. He was looking to sign up new retail clients, including in Maryland.

He came into Irjax’s backyard and formed an alliance with retailer Mark Feldman, owner of Maryland Funnybook Shop in Silver Spring. Feldman would serve as a subdistributor for Seuling, obtaining products for his store and then acting as a wholesaler for other stores in the area.12

Examples of this model had already happened in other metro areas. Seuling found retailers to serve as his middlemen. These coveted roles often went to friends and associates he had met through his conventions. In almost every market, competing retailers found themselves in the awkward position of having to buy from their local rivals if they wanted to have the advantages of Seuling’s services.13 At that time, several small comics distribution companies were trying to build and sustain regional territories. Some of them, such as Irjax, saw Seuling’s expansion as an existential threat.

Hal Shuster of Irjax / New Media (left); Mike Friedrich (below right) speaking with Dean Mullaney, who was then an editor at Eclipse Comics. Both photos from the 1982 San Diego Comic-Con. Credit: Alan Light.

Irjax and Seuling started to trash each other in conversations with potential clients. Seuling would say that Irjax was a small-time operator that didn’t know what it was doing. Irjax would say that Seuling was secretly bleeding money and about to go out of business. The comments, made in private, were not unusual for the rough-and-tumble world of comics distribution. Then Seuling kicked it up a notch with this note in his November 1977 newsletter to customers:

A notice I think is probably unnecessary: For a few months, an off-the-wall pseudo “distributor” on the middle of the East Coast has been telling everyone that “Seuling is out. He won’t be able to deliver books any more.” This nut has also suggested returning unsold books (bought from him) through the local distributor as “returns,” a policy which would automatically get you cut off from all supplies from all publishers. . . .

Additionally, this sickie made threatening and harassing phone calls, and has used the mails fraudulently. He is inches away from deep (Federal) trouble. And yes, I intend to prosecute.14

Hal Shuster saw this and was livid, according to Levas. The part that most incensed Shuster was the use of the word “sickie,” which he took as a reference to his father. Irwin Shuster used a wheelchair, and his sons were sensitive about anything that seemed to be making fun of this.

“That’s certainly not cool to have written that, but that was Phil, impetuous and headstrong,” Levas said. She thinks the newsletter, as much as any business disagreement, is what made the conflict escalate into what would turn into a legal quagmire.

On October 2, 1978, Irjax Enterprises filed suit in Maryland federal court against Seuling and just about every major comics publisher, accusing them of violating antitrust laws. At its heart, the case was about how Seuling and Sea Gate had more favorable terms with publishers than Irjax did. The most glaring example may have been the way Seuling could get his customers’ orders collated and shipped directly from the printer, which meant his clients received items sooner than his competitors’ clients did.

What Irjax was doing was audacious. The company was a small business, and it was suing some corporate giants. Among the nine defendants were Warner Communications Inc., the parent company of DC, and Cadence Industries Corp., the parent of Marvel. Other retailers and distributors had talked about suing Seuling and the publishers, but only Irjax was willing to take the risk to its finances and reputation.

In the lawsuit, Irjax claimed that the defendants “have engaged in an unlawful combination and conspiracy in restraint of interstate trade and commerce” and have “endeavored to force Irjax out of business of wholesale distribution of comics books and related items.”

Along with the antitrust claim, Irjax also made a libel claim against Seuling for the comments in the newsletter. The court filing says Seuling’s letter had been mailed to many of Irjax’s customers, contained statements that Seuling knew were untrue, and was “clearly intended to, and did, hold plaintiffs up to contempt and ridicule.”

Two months later, in an amended complaint, Irjax provided some additional details about how all the defendants fit into the larger comics business. The filing said that Marvel accounted for 70 percent to 75 percent of sales to comic shops; DC was 20 percent to 25 percent of sales; and Warren Publishing, known for Vampirella and other horror titles, had 4 percent. Marvel was dominating the industry, while DC, the former industry leader, was struggling. Warren would go out of business a few years later.

Seuling was not the type to walk away from a fight. He responded to the lawsuit by denying the allegations and then making claims of his own against Irjax and the publishers. He also added a claim against Big Rapids Distribution of Detroit, a company that had not been named in the Irjax lawsuit but was a competitor of Seuling’s. His argument, in essence, was that Irjax and Big Rapids were the ones getting favorable terms of service from the publishers.

From there, many lawyers expended many billable hours. Filings piled up at U.S. District Court in Baltimore. Beyond the nuts and bolts of the case itself, the publishers came to the realization that distribution to comic shops was becoming a big business, and it needed to be handled in a more organized way. No more handshake deals. From then on, Marvel and DC would seek to have uniform terms of service.15

By the summer of 1979, less than a year after the Irjax complaint had been filed, the major issues had been resolved in a series of settlements. The upshot for Seuling was that he would no longer receive terms of service that were different from what other distributors got. His time as king of the business was waning. Meanwhile, the number of comic shops continued to grow. Irjax, Big Rapids, and others had a wide-open playing field in which to sign up customers, leading to the next era, one marked by chaotic competition, rapid rises, and even more rapid falls.

This was about the time that the “direct market” stopped being quite so direct. The term had come from the fact that Seuling’s retailer customers were getting orders shipped directly from the printers, bypassing news distributors. In part because of the lawsuit, the system shifted to one in which comics distributors set up warehouses to receive material from printers, collate it, and then ship it. This was still better than the old system with news distributors, retailers said, but the straight line from printers to stores was gone.

It would be easy to say the Irjax lawsuit is what knocked Seuling from the top of the industry, but there were many other factors. Among them was that Seuling and Sea Gate continued to require prepayment and other terms that made it difficult for customers. And now some comic shops had been around long enough and become large enough that their owners felt comfortable making their case for change.

Among the outspoken retailers was Chuck Rozanski. He had gained a national profile in the industry for having acquired the Edgar Church collection, one of the largest and best-preserved troves of Golden Age comic books that had ever changed hands. He gradually sold the collection and used the proceeds to build Mile High Comics into what remains one of the country’s largest mail-order dealers of back-issue comics.

In the spring of 1979, while the Seuling-Irjax lawsuit was still active, Rozanski decided to write Marvel Comics to raise his concerns about the ways that the comics market was falling short of its potential. The letter was sent to Robert Maiello, Marvel’s manager of sales administration.

Chuck Rozanski in his original Boulder, Colorado, store in the late 1970s. Courtesy of Chuck Rozanski.

Here it is in its entirety:16

Dear Mr. Maiello:

My name is Charles Rozanski, and I own Mile High Comics. I am one of the largest comic book retailers in America (sales 1979 about $400,000), and thus a customer of yours. I am also a small advertiser in your comic books. This letter is an attempt on my part to bring to your attention some suggestions which I believe will be relevant, if your job truly encompasses sales and promotion.

To begin with, I have been an active retailer of your products for over four years. Starting with no more than 15 of any comic title, I am now purchasing over 10,000 Marvel comics a month on a nonreturnable basis. I get these books through Seagate Distributing (Jonni Levas, Phil Seuling). It is my latest order with them that has especially prompted this letter.

My order (of which a photocopy is enclosed) for your products is just under $4,000 for this month. These are books that will arrive between June 10 and July 10. Under your existing policies you have just lost at least $1,000 in sales. The reason: After putting my order together I cut my list to the bone in order not to have to lay out any more up-front cash than was absolutely necessary during May, a slower month for my business. So, we both lose: you lose my business, and I lose those sales that I could have gotten by having a reserve instead of ordering just barely enough for my guaranteed sales.

Why is this foolishness still necessary? In November of last year an “outside consultant” who supposedly was representing Cadence Industries / Marvel Comics approached us about direct contact with your office and the possibility of some mutually beneficial programs. He told us he would get back to us in December. We have heard nothing. Did you send out a representative? If so, did he present you with a breakdown of what is happening? I am going to take your silence of the past six months as evidence that either the “consultant” in question did not really work for you or else did his job very poorly. Or, there is one other possibility. Did he tell you that you would be better off without us? Is this why rumors of a lawsuit on predatory pricing are circulating? For your sake and mine, I hope not.

Whatever the case may be, I think it is about time you heard from a retailer directly. Ours is a dying industry and if we don’t get together and cooperate there will be no comic books at all. If you don’t believe me, check with John Goldwater, the president of the Comic Magazine Association of America. According to him, circulation from 1959 to 1978 dropped from 600,000,000 to 250,000,000. This alone should be enough for your office to be highly interested in actively seeking to expand our business as much as possible.

Well this has not been the case. The policies currently in force are restricting severely the ability of comic book retailers to grow or even in some cases to stay even. How can you justify continuing to require advance payment for all comic deliveries? Do you realize the cost in lost sales of this policy? As I pointed out earlier, I would have spent another $1,000, this month alone, on your products. Multiply my business by the hundreds of independent retailers, large and small, across the nation, and you come up with a staggering sum that is being wasted. Stop and think, what is the variable cost of a 40 cent comic? When you have already paid all your costs except paper and shipping, how much does it cost to leave the presses running for another 10,000 copies? My guess is between 3 and 5 cents a copy. In a business with razor thin margins, you can’t afford not to get every bit of profit available.

And don’t be misled, we do not siphon off business from existing distributor accounts. Quite to the contrary, we salvage thousands of customers who otherwise would have left the field in disgust at the poor distribution. When you print continued stories, it is imperative that the customer who wants the next issue should be able to find it easily. This is not currently the case. Comic books are among the lowest items on a normal distributor’s priority list. And thus the whole point of continued stories (i.e. creating customer demand for future issues) is lost, and instead the opposite occurs as customers quit buying from frustration. Pardon me for being the one to say it, but that is stupid.

Another point is that we do not just salvage customers you otherwise would have lost, we also create new ones. At 40 cents and up, comics are no longer able to sell themselves. You have made the product so thin and unattractive with advertising that it takes salesmanship to get them to sell, even to collectors. How much salesmanship do you get in a 7–11? We go out of our way to sell comics, they are our main business. (For example, the Superman the Movie book from DC . . . I set up a stand in a local theater and sold over 1200.) Isn’t it about time we got some help and support?

Well enough of generalities. After four years I have some concrete suggestions that will make you money and make me money. Here they are:

1. Give us billing, or at least COD purchases.

2. Start a cooperative advertising program to promote comics.

3. Pay for artists and writers to do promotional tours.

4. Give us better information about what is coming out. We will buy many more books if the uncertainty about artists, etc. is alleviated.

5. Start up a listing (on one of the ad pages) where comic book retailers could list themselves at cost.

6. Make it an editorial policy to support us. Present policy never even mentions we exist.

7. Ask us for feedback. When you do something, we hear about it, believe me.

8. Set up a remainder sales division. Since I, and many other retailers, also sell back issues, we would buy thousands more comics if they were available at a remainder price instead of normal cost.

While I realize that not all of the above suggestions are currently viable, at this point anything would be better than the situation as it exists. I sincerely believe that I am echoing the sentiments of other independent dealers when I say I am tired of not getting any help from you, the people who benefit from my efforts. Right now, comics are my life. I work seven days a week, ten to twelve hours a day, to make my business exist and your business better. And you have been no damn help at all.

So please give me some feedback. We are both in the same business and cooperation between us can do nothing but make our mutual jobs easier and business more profitable. I’ll be awaiting your reply.

Sincerely,

Charles W. Rozanski

P.S. I am going to distribute this letter as widely as I can and ask my fellow dealers to send you signed copies to indicate their agreement with most of my points. Without an official organization to support us (we are all very independent) this is the best I can do to prove that other dealers are in agreement with my opinions.

Rozanski received a reply from Ed Shukin, Marvel’s vice president for sales, who invited him to come to the company’s offices in New York to discuss the matter further. Soon after, when Marvel was setting its terms of service following Seuling’s lawsuit, the publisher threw the door open to businesses that wanted to become Marvel distributors. The standard of entry was a certain monthly order threshold. According to Mike Friedrich, who soon would be working in Marvel’s sales department, the level was intentionally set so that Rozanski would be just above what was needed to become a distributor. More than a dozen businesses set up distribution deals with Marvel.

The dominance of Seuling was done, replaced by a much messier and more complicated mix.

Indie-Minded Elves

Wendy Pini, cocreator of Elfquest, became one of the first star artists to reach fans mainly through comic shops. In hindsight, she is a pioneer for independent publishing and for women in comics. At the time, she was just a young creator trying to find an audience. The following are excerpts from our interview.

Becoming an Indie Publisher

After being turned down by Marvel and DC and several others, we knew we pretty much had to Little Red Hen it. The story and characters were in my blood and I was passionate—obsessed, really—with getting it out there any way we could. We’d discussed writing it as a prose novel or as a screenplay. But in the end we both decided that the art was just as important as the words. So the comic format was ideal.

At the time we were impressed with indie publications such as Star*Reach and First Kingdom (our actual role model for the magazine-sized format). Richard taught himself from scratch how to be an indie publisher. I dove blind into the deep end of writing and drawing a series. Had no idea how much work it was going to be or how hard.

Therefore I blush to admit the issue of my being a woman pioneer in the male-dominated comic scene didn’t loom very large for me at the time. I just wanted to push ahead on the strength of my work. Also I soon became so consumed by deadlines that I didn’t have any energy to devote to the political side of things. I’m honored to be regarded as an innovator, now. But I was completely naïve, stubbornly single-minded, and driven back then. What we were—underground, indie or mainstream—never mattered as much as “Can I get the damn thing done close enough to deadline so Richard won’t kill me?”

The Role of Comic Shops

Without comics specialty shops I’m certain we would not have been the overnight success we were. What we owed, back then, to the positive word of mouth of comic shop owners—plus exposure at early comic conventions, particularly San Diego—is incalculable. It was all word of mouth in the late 1970s and early 1980s. But it spread damn near as fast as the Internet does now. Elfquest grew up right along with the burgeoning of comic shops all over the country.

What Elfquest did was bring in a new kind of readership to the comics market. It brought in fantasy and sci-fi readers, a lot of them fans of my prior work, who weren’t all that familiar with the comics medium. But they were eager to get to know the elves.

Most important, Elfquest brought in an unheard-of female audience. Girls were haunting comic shops like never before. Elfquest was responsible for opening up a new dialogue about who comics were really for. All at once women could say, “Keep your superheroes and your Archies! We’ve got this now!” As a result, and as more eclectic indie titles started to come out, comic shops had to clean up their act a bit and become more female-friendly.

Being Red Sonja

On a more serious note, despite those who have occasionally claimed that my Red Sonja cosplay has haunted me all these years and caused me to be taken less than seriously as a creator, I say the notoriety gained from portraying Sonja opened very important professional doors for me in the comics industry back then. It got my name and certainly my picture out there. . . .

Rather than hinder me, my association with the Red Sonja character brought me attention and, oddly, a certain amount of respect. I took my performances seriously. This was far from just T&A to me. And there were some—not everyone, but some—who seemed to get that. There had never been, and there hasn’t really been since, a multimedia presentation like “The Red Sonja and The Wizard Show” at comic cons. It was unique in how it delivered a powerful feminist message with a spoonful of ale-soaked sugar. I will always remember it fondly and proudly.

Wendy and Richard Pini posing in the late 1970s.

Wendy Pini as Red Sonja.

With the success of Elfquest came merchandising. Photos courtesy of Richard Pini.