Читать книгу Oppy - Daniel Oakman - Страница 4

ОглавлениеPrologue

Buffalo Vélodrome, Paris, 1 September 1928.

The evening air was cool and still. Groups of cyclists milled nervously in the centre of the velodrome. Some distracted themselves by fussing over their bicycles, adjusting tyre pressures or tweaking a seating position. Some discussed tactics, pacing strategies and food. Some talked about the prize money. All inspected the track, a banked concrete oval, about 500 metres per lap. By the end, their bodies would know every furrow of its rough, uneven surface.

No-one was getting any sleep this night.

The men were about to start one of the toughest events on the world cycling calendar, the Bol d’Or, the Golden Bowl, a non-stop twenty-four-hour endurance race designed to break the physical and mental resolve of all but the strongest.1

Among the assembled riders was a young Australian road cycling champion, Hubert Opperman. Months earlier, he had completed the gruelling Tour de France, the toughest event of his career, but he still hesitated at the prospect of twenty-four hours of near continuous pedalling. The start drew nearer. He worried about the last time he had raced such a distance in Victoria, when he faltered in the closing hours. He thought about the European titans who had won this great event before, not to mention the experienced road veterans who stood before him. Were their minds also flooded with doubt?

While the race was a solo event, each competitor would be paced by teammates riding tandems or triplets. Fresh pacemakers could be exchanged at any time, but the laps would only be counted on the position of the solo competitor. At 11pm, the starting gun sounded and twelve contenders took off behind their pacers. Confusion reigned. Teams found their rhythm, jostled for position or attacked, hoping to put some early laps into their rivals.

In the ‘mad melee’ Opperman hit a back wheel. In the struggle to remain upright he wrenched the handlebars loose from the forks.2 With handlebars swinging wildly in the corners he kept pedalling as best he could. He hoped that the pace might slacken just enough for him to change bikes without falling too far behind. It did not. His pacemakers looked behind, unable to understand why their man could no longer follow their accelerations. Then, an hour later, Opperman felt the power leave his rear wheel. Looking down between his legs he saw the chain dangling from the cogs. He rolled off the track into the centre of the velodrome. Opperman’s manager, Bruce Small, stood by with his spare machine. Before handing it over, Small noticed the handlebars were also loose and quickly tightened them. Three laps down. The pacemakers urged their rider on. ‘Allez, Oppy!’ ‘Come on!’ Opperman stood on pedals to bring more energy to the wheel, when he suddenly slumped forward. Another chain had broken and now hung uselessly from the chain wheel. Chain breaks were not uncommon, but two breaks in such quick succession were almost unheard of.

Now with two chainless bikes, Small frantically tried to borrow one from a rival team. They refused, as sanctions applied to teams who were considered to have colluded. Opperman scrambled for a machine, any machine. He jumped on a nearby roadster, a heavy touring bike with mudguards, a lamp and, worst of all, a low gearing ratio that limited the top speed. For every six laps taken by the field, Opperman could only manage five. By now the news had spread through the crowd that the Australian’s bikes had been sabotaged. Someone had loosened the steering tubes and filed chains until they were so thin that they would snap when extra force was applied to the pedals. The crowd had found its hero and began pouring a storm of hatred over the perpetrators. They cheered for Oppy to take his revenge.

‘Allez, allez, allez, Opperman!’

By the time Small had repaired the track machine Opperman was seventeen laps behind. He pleaded with his pacers to raise the speed to make up the deficit. ‘C’est impossible,’ they moaned. On each lap, Opperman yelled to his manager to find some more willing pacers. Small found some among the teams who had already abandoned the race. With a deal struck quickly, the new riders joined the chase. Opperman began clawing back the lost laps. After ten hours of racing, he was just four laps behind the leaders. By now Opperman’s bladder demanded attention. Having worked so hard to regain position he refused to leave the track. ‘Doucement, doucement!’ he shouted to his pacemakers. They were perplexed at the sudden request to ease up. The crowd erupted when they saw a stream of golden urine flying from Opperman’s rear wheel and into the faces of his pursuers.3

Strategies for bladder relief have always been important in bicycle racing. An experienced French rider once advised Opperman to always be the last to take a toilet break. In this way, he could gain a few laps before having to stop himself. Ever the opportunist, Small suggested that Opperman adopt his road practice of not stopping at all. This feat was made more difficult because unlike on a road bike, which could be fitted with a freewheel hub that allowed the bike to roll without the cranks and pedals moving forward, a track bike has a fixed wheel. When the wheel turns, so do the pedals and of course, the rider’s legs. Oppy had taken Small’s advice to heart and in the days before the race practiced his technique on a fixed wheel machine on some quiet roads around Paris.

The now relieved Opperman returned to his task. After twelve hours he fell into a ‘slough of monotony’ looking for any distraction from the infernal turning to the left. Small worked from the sidelines ordering riders to different positions, putting the smallest riders to the front and the larger to the rear to maximise the aerodynamic benefits. Opperman’s grit had won the crowd’s heart. ‘Allez, allez, allez, Oppy’, they chanted. By midday the remaining riders began to tire. Four cyclists had dropped out, including the much-feared Achille Souchard, the French national road cycling champion and Olympic gold medallist. Opperman ordered a savage acceleration to further demoralise the remaining riders. At the fourteen-hour mark, he had covered 400 kilometres with his nearest rival over thirty laps behind. The best of Europe had fallen away. Winning seemed a formality.

‘Allez, allez, allez, Opperman’, they sang.

He would tell the story of the Bol d’Or for the rest of his life. It never failed to move him. ‘To be at last in front of a Continental classic, to know that a dream was almost true,’ he recalled, ‘to hear this musical roar’ was ‘to be transported to the heights of pedalling inspiration.’4

Opperman had ridden at over forty kilometres per hour for twenty-four hours. He had covered 950 kilometres and was over 100 laps ahead of his nearest rivals. In the end, it was a clinical demolition of the opposition, including French hard-man and last year’s winner, Honoré Barthélémy, who had been forced to abandon the race.

Opperman desperately looked forward to ‘bouquets and bed’, but Small sensed another opportunity. Oppy’s speed and his ability to ride without rest had put him on schedule to beat the 1000-kilometre record. Opperman refused to continue. Small explained to the exhausted rider that he would feel no more or less tired tomorrow if he continued to ride. Not for the last time, Opperman gave in to his astute manager’s irrefutable logic. Small had already arranged another squad of pacemakers to help him cover the required distance. Opperman dutifully strapped his feet to his pedals and rode for another hour and nineteen minutes, all to the rapturous applause and chanting of the crowd. Just after midnight on Monday, a great mass of spectators surged onto the street and Opperman was carried, shoulder high, from the track.5

Race fixing, collusion and other forms of skulduggery marred professional cycling in the early twentieth century. Those who tampered with Opperman’s machines were never discovered. Although such actions were unsporting and dishonourable, the saboteurs were right to fear the ‘little Australian’ in their midst. The French sports newspaper L’ Auto – never shy of hyperbole – declared Opperman the greatest all-round cyclist in the world and his victory as the most thrilling performance the French public had witnessed for many years.6 But his ride at the Buffalo Vélodrome confirmed what the sporting press had suspected throughout that year’s Tour de France: that Opperman was a spectacularly gifted cyclist who combined great speed with prodigious stamina. Some likened Oppy’s capacity to Léon Georget – known as ‘the Brute’ – an endurance powerhouse and nine times winner of the Bol d’Or. But they sensed that Opperman possessed something more. They dubbed him ‘le phénomène’, the phenomenon.7

Australia already knew Oppy. But success in Europe propelled him to fame and fortune still unimaginable to the twenty-four-year-old rider from Rochester, Victoria.

And this was only the beginning.

* * *

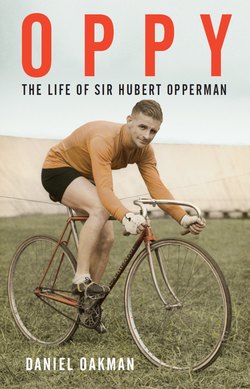

No-one saw him coming. A short, lightly built lad with wing-nut ears and an easy grin, he was hardly the most imposing of men. His unlikely look and unassuming manner fooled many competitors – in the beginning, at least. What set Hubert Ferdinand Opperman apart from his generation could not be seen. The will to win is common to all athletes. But Opperman rode with a determination so furious, blinding and irrepressible that it left competitors andfans awestruck.

Opperman electrified Australia and the cycling world with his unique combination of discipline, desire and an enormous capacity for suffering. Unlike any other cyclist, then or now, it was Opperman who set ‘humanity on fire’, to use the beautiful phrase coined by his Italian rival Giuseppe Pancera.8 For an athlete who became an international cycling super-star, an icon of the sport, it is curious that most Australians know so little about the man they called ‘Oppy’.

This book tells the story of how a young cyclist with a breathtaking talent became one of the most potent and transcendent figures in Australia’s sporting history. Whether he was racing in the Tour de France or crossing the vast Australian continent in record time, millions admired Opperman as a consummate athlete, a humble and approachable champion and the epitome of good sportsmanship. In Australia, like the cricketer Don Bradman, and the racehorse Phar Lap, Opperman became a unifying cultural force during a time of painful economic and social change. Yet his contribution to public life did not end when he retired from professional racing in the late 1940s.

Opperman’s life, which he himself described with characteristic understatement as ‘varied’, spanned almost the entire twentieth century. He was intimately involved in the making of Australia’s social, cultural and economic history – first as a professional athlete, then as an influential minister during the Menzies era and latterly as Australia’s first high commissioner to Malta. His fame helped make his sponsor, Malvern Star, the most coveted bicycle of a generation, from big name professionals to boys and girls riding to school or the local shops.

This biography also examines Opperman’s entry into federal politics and his relationships with key political figures of the time, including Richard Casey, Robert Menzies, Harold Holt, Bob Hawke and Malcolm Fraser. It explores his ideas about economic development, national fitness, car culture, the assimilation of migrants, and the treatment of Aborigines. It pays particular attention to his contribution to the reform of Australia’s immigration policy in the 1960s.

Opperman’s life is shrouded in myth. After peeling away decades of nostalgia, he emerges here as a more vulnerable, complex and nuanced figure than his legend has allowed; a far cry from his reputation as the mild-mannered, ‘simple, uncluttered Hubert Opperman’, as one of his political friends remembered him.9 By looking at the man behind the myth, the story explores the controversies that dogged his sporting and political careers, the emotional pain of his private life, and the nature of his racial politics. More than any other account of Opperman’s career to date, it delves deeply into the life of one of the world’s greatest cyclists and an extraordinary Australian.

_________

1 Le Sport Universe lllustré, No. 1334, 22 September 1928, p. 634.

2 Sports Novels, December 1947.

3 Hubert Opperman, Pedals, Politics and People (Sydney: Haldane Publishing, 1977), pp. 119–120.

4 Sports Novels, December 1947; Opperman, Pedals, p. 120.

5 Beverley Times, 24 February 1950;Cycling (UK), 17 November 1949.

6 Sporting Globe, 5 September 1928.

7 L’Intransigeant, 4 September 1928.

8 Pancera to Opperman, 1970, MS 6429, Box 13, Folder 72, NLA.

9 Hansard, Senate, 30 April 1996, p. 31.