Читать книгу Oppy - Daniel Oakman - Страница 7

ОглавлениеChapter 3

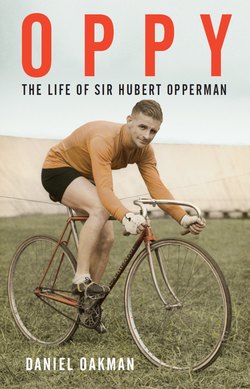

Scratch Man

When Opperman smiled for the cameras, his cheeky, impish grin widened just enough to show a mouth of chalky, broken teeth. Most people being photographed in the pre-fluoride era chose to contain their broad smiles, but this was proving increasingly difficult for the young cyclist as he won more races and had more pictures taken for the newspapers.

Since his late-teens Opperman suffered from toothache. Like most of his generation, he accepted infections and cavities as a part of life and resisted all entreaties to visit the dentist. His health – and his cycling – started to suffer. Bruce Small, who now served interchangeably as Opperman’s coach, mentor and father figure, told him to get them looked at. When he did, he left the dental rooms without a single tooth in his head. Once his gums healed he ‘returned to buoyant health’ with a corresponding improvement in his training and racing results.1 The price was a lifetime of using dentures, yet another feature of early twentieth century life that typically passed without complaint.

* * *

Before Opperman left the public service, he had started track racing at Melbourne’s most popular cycling venue, the Royal Exhibition Buildings in Carlton. He did so, not because he had developed any notable capacity to sprint, but because it paid. The outdoor track had been at the centre of the cycling craze that captured Australia in the late nineteenth century. Improvements to the viewing facilities and the installation of floodlights in the early twentieth century made the arena a spectacular venue for track racing in Australia. Weather permitting, track events were held twice a week and attracted thousands of paying (and betting) spectators. Contracted cyclists could supplement their regular income with generous prize purses, as well as ‘lap’ or ‘sprint’ prizes offered to create interest during the events.2

Opperman relied on his staying power to earn his prize money. To increase the interest in the track events, ‘lap prizes’ were on offer to those riders who led the field at certain stages of the race. Pushing to the front early in the piece, Opperman took advantage of the sprinters and their reluctance to expend too much energy before the final dash to the line. On a good night, Opperman would expect to take between five and ten laps and £2 or £3 in winnings. He became known as the ‘Lap King’. This was solid and reliable riding, if a little too conservative to be considered exciting. Nevertheless, it provided a handy supplement to his regular income and kept his name in the papers and on people’s lips as a rider to watch. All the while he developed his physical capacity and his tactical nous.

In early 1923, having had a chance to observe his racing more closely, Small reckoned that Opperman might be suited to the latest craze that was sweeping sports arenas around the world: motor-paced cycling. Loud, fast and dangerous, motor-pacing offered spectators the thrilling combination of a human-powered bicycle and a mechanically power motorcycle. Specially modified motorbikes, where the rider sat in an almost upright position, allowed a cyclist to ride in the slipstream. Without the normal wind-resistance to restrict the bike rider’s progress, the best cyclists could achieve speeds in excess of 100 kilometres per hour, although speeds of between seventy and eighty kilometres per hour were more usual. The bicycles were fitted with huge front chain rings to generate the necessary speeds. A smaller front wheel was often fitted to lower the rider’s profile in order to gain more protection from the wind. The pacing machines had a roller set behind the back wheel to avoid crashes caused by the rider’s front wheel touching the back wheel of the motorcycle.

Motor-pacing racing was wild, working-class entertainment. If road cycling attracted the cycling connoisseur, then motor-pacing was for the drinking, gambling masses. It also attracted flamboyant promoters and reckless, hot-headed cyclists who manipulated betting odds by making outrageous statements to the press. The combination of using human and non-human power to race around a circular track was a visceral echo of the horse-drawn chariot contests around the hippodromes of the ancient world. Although officially sanctioned by Australia’s cycling governing bodies, motor-paced bicycle racing was a largely self-regulated affair. Which is to say, that for the most part, it was unregulated and suffered from all the showmanship and jiggery-pokery that one might expect from such theatrical entertainment. For spectators, its primal appeal was undeniable. Spectacular (and sometime fatal) accidents on motor-pacing arenas added to the excitement and interest of the paying public who attended in their thousands.

For Small, getting his bikes seen at motor-pacing events was an important commercial opportunity to show the versatility, speed and reliability of Malvern Star machines. Motor-pacing was also a happy convergence of his passion for bicycle and motorcycle racing. No slouch astride the motorbike himself, Small had set the world speed record for racing a motorcycle and side-car over one mile before he ventured into the bicycle business. The sheer range of Small’s interests was a constant surprise to Opperman.

By virtue of his small stature and smooth pedalling action, Opperman was ergonomically and aerodynamically suited to motor-paced racing. Tucked in behind a skilful motor-pacer, Opperman’s excellent stamina could also help him simply outlast a more powerfully built rival in the longer contests.

When the mercurial sports promoter at the Exhibition track, Jack Campbell, rebuffed Small’s attempts to get Opperman a race at the venue, he simply decided to stage one himself. If racing behind motorcycles on public roads was illegal (and it was), Small was not the kind of man to ask for permission. One Saturday afternoon, Opperman lined up next to his hero ‘Bowie’ Stevens – the man whose Adonis-like form he had gazed upon four years earlier – and prepared to race over one mile. When the traffic cleared, they roared down Dandenong Road tucked in behind the specially modified pacing motorbikes at almost seventy-five kilometres per hour. The race was over in less than a minute and a half and Opperman won by a single second. The papers quietly reported the results, but the stunt was exciting enough to pique Campbell’s interest and for Opperman to be offered a ride at the Exhibition Oval.

Opperman’s first race on the notoriously tricky track nearly ended in tragedy. Without warning, his front tyre rolled off its rim, pitching him onto the track directly in front of his opponent’s motor-pacer, Bob Finlay. Known as one of the best in the game, Finlay altered course narrowly avoiding crushing the sprawling Opperman beneath the heavy motorcycle. Opperman refused to give up and fearlessly returned to the track. The handlebars and saddle were switched to another frame. With heavily bandaged arms and legs Opperman rode, and won, the next two heats. Campbell liked what he saw and booked Opperman to race the next season.

The following Monday, Opperman hobbled into Campbell’s bicycle business in Prahran to collect his winnings. Never one to miss an opportunity, Campbell tried to poach the young rider, offering him double his present salary, two days off a week to train and free access to all the bikes and equipment he desired. Stunned by the overture, Opperman went to work and explained what had happened. Small confessed that he couldn’t match the offer and that he would understand if he accepted. Yet, for Opperman something wasn’t right. In the cutthroat world of sports entertainment, he did not trust Campbell to look after his interests should he be injured or if his results ever faltered. Opperman swore his loyalty to Malvern Star and Small swore that his commitment to the young rider went beyond mere short-term gain. The equation was elementary, as Opperman recalled, ‘I sought success on the wheel – he sought spectacular returns for Malvern Star.’4 But it was more than this. Their relationship was not merely an alliance of their respective sporting and commercial goals. They had become friends.

Not even the astute business mind of Bruce Small knew how long the motor-pacing fad might last, though he intuited that its attractions would fade sooner rather than later. Opperman continued to compete on the track and in motor-pacing. But both men knew that the long-term future of cycling in Australia would be in road cycling, with its greater popularity and established traditions. Road racing, though far from safe, offered a more sustainable and less dangerous career than motor-pacing. By the end of winter, as another road season loomed, Opperman began diverting his energy towards making his biggest mark on the Victorian racing scene to date.

Victorian road cycling revolved around a staple of annual races that traversed much of the state. Like the road and railway networks that crisscrossed the land, bike races provided another kind of link between the rural heartland and the city. Separate events from the east, west and north of the state converged on Melbourne. The big races from Ballarat, Bendigo, Colac, Geelong, Sale and Warrnambool brought economic benefits to the hundreds of towns and villages they passed through, as well as proving a focus for regional cycling clubs. Importantly, they offered aspiring local racers an inexpensive opportunity to test their legs against riders from outside the area. By radiating toward the capital, these races symbolically confirmed Melbourne as the hub of Victorian (perhaps even Australian) cycling. No other capital city was connected by such a network of sporting energy in quite the same way.

Riders wanting to assert their talents typically targeted one or two of these races a season. Opperman tackled them all. He started the road season knowing that he now rode as an equal to the best in the state. Earlier in the year, Victoria’s cycling officials removed his handicap, finally bestowing upon Opperman the most coveted position in racing. He was now a ‘scratch man’. No longer would he have to leave ahead of the best men in the field and hope to ride in their slipstream as they passed. Now it would be for others to fear his remorseless pursuit, just as he had dreaded the inevitable ‘catch’ from the strongest riders. He raced with ever growing confidence and his name began to appear on the result sheets with increasing frequency.

A major breakthrough came with his performance in the season’s first Sale to Melbourne race, when he took fastest time in windy conditions beating his cycling idols, Ernie Bainbridge, Don Kirkham and the NSW champion Ken Ross. The Monday after the race, Small took his ‘dashing young rider’ into the offices of the Sporting Globe, Victoria’s popular sports newspaper. Determined that Opperman should overcome his natural modesty, he hoped that his flair for storytelling might come across to the reporter. Although still uneasy with the attention, his ability to compress his eight hours of toil into a good yarn became clear. He spoke about racing with an authority and immediacy that sports journalists (and most professional sportsmen, for that matter) could not:

Reaching Dandenong we learned that we were six minutes behind the front bunch, who were reported to be sailing along at a good turn of speed. The road was swarmed with motors, cycles and other vehicles, and it was with some difficulty that we threaded our way through the vast crowd.

We were coming to the end of our long journey, and, as we swung into Caulfield half a mile from home, Don Kirkham lead out and made the pace a cracker for a quarter of a mile. When I realized how far the finishing sign was, I found that I had sprinted a bit too early. Glancing under my arm, I saw that I managed to hold it over Bainbridge and cross the line first. There a vast crowd of 10,000 had waited for hours to welcome home the winners.5

The relationship with the Sporting Globe lasted many years and became critical to cultivating Opperman as a sporting celebrity, as well as educating the cycling public about the finer points of racing at the highest level.

Every professional rider in Australia raced and trained with an eye to the Warrnambool to Melbourne. Even by the 1920s, the ‘Warny’, as it later became known, was already steeped in tradition. First run in 1895, it was regarded as the greatest and the toughest road race of the year, a contest where ‘virile and young cyclists [came] to meet on level terms’.6 The race was (and still is) Australia’s oldest one-day classic and the world’s second oldest, after the Leige–Bastogne–Leige in Belgium. Although a handicap event, until 1939 the title of Road Champion of Australia and New Zealand went to the rider who achieved fastest time over the full distance of 266 kilometres, even if they did not take line honours. There was no greater prize on the Australian racing calendar.

In ordinary circumstances, the idea of a wispy nineteen-year-old lad taking the great crown of Australian road cycling champion seemed preposterous. In addition to the dusty, rock-strewn roads that plagued most road races, the defining factor in the ‘Warny’ was the wind. Crosswinds from Bass Strait ripped across Victoria’s western districts with monotonous consistency. With few hills to give advantage to the lightweight climbers, the race was usually won by heavier, well-muscled riders, better equipped to power into a gale. But as racing observers had begun to realise in the last year, nothing about Hubert Opperman was ordinary. Two weeks before the great race, Opperman travelled to Tasmania for the Launceston to Hobart. Yet again, he produced the fastest time ahead of Don Kirkham with a ride considered ‘nothing short of miraculous’.7 Finishing fresh faced and seemingly unaffected the ‘great little man’ was ‘cheered enthusiastically and carried off the ground by barrackers’.8 Opperman’s ascension to the throne seemed inevitable.

Good form, experience and smart tactics were important for racing success. But there was always the question of luck. When Opperman arrived at the start of the 1923 Warrnambool to Melbourne, he was considered the rider most likely to test the defending champion, New Zealander Phil O’Shea. The race began well. The weather broke fine and mild. Opperman avoided the early crashes and usual hurly burly of the opening miles. Then, about fifty kilometres outside of Geelong, a hiss of air signalled the end of his chances. The bunch, containing the top contenders for victory, pedalled into the distance. He was left scrambling to repair his flat tyre. Regaining the leading group of such high calibre riders would be unlikely. His best chance would be for the coarse metalled Victorian roads to inflict misfortune upon the front-runners. It was not to be. He rode on and finished with the fourth fastest time, around three minutes behind O’Shea’s winning ride.9 The press noticed his ‘undaunted’ and plucky response to misfortune, but it was nevertheless a disappointing end to a season in which he appeared to have an unstoppable momentum.10 He would have to wait twelve months for another attempt at the elusive title.

Opperman returned to motor-pacing, further honing his skills. By early 1924, he had become a regular fixture at the Exhibition Oval, smashing records and beating all comers. ‘Experience is making a wonderful difference with the Malvern lad who is sitting behind the roller with much more confidence than he did at the outset’, observed the Sporting Globe.11 Cycling fans also knew the talent pool that could be pitted against the likes of Opperman was relatively shallow, with many of Australia’s best motor-paced riders, such as Cecil Walker and Reggie McNamara, pursuing lucrative deals with track promoters in Europe and America. Naturally enough, by mid-1924, Opperman wondered if he too should look for opportunities abroad.

Opperman made inquiries with the Newark Velodrome in New Jersey, considered the cradle of American track racing. Unable to find a sponsor, he later heard from his friend Roy Johnson (also racing at Newark) that Walker, perhaps fearing Opperman as a rival, had played a role in scotching his attempts to get noticed. Yet, it is also likely that Opperman’s reputation hadn’t quite developed sufficiently to transcend national borders. He may also have lacked the flash and braggadocio that attracted American promoters. Small, presumably, must have been less enthusiastic about his great prospect leaving Australian shores with the Malvern Star business only just beginning to expand.

Missing out on the United States was probably a blessing. American promoters worked their riders hard, with many insisting on six nights of racing a week. The specialisation in short-format, high-speed racing would have left Opperman with little time or energy to develop and extend his endurance riding, which was emerging as his strongest attribute.

Opperman’s modesty masked an overweening ambition. At this stage of his life he did not seek fame, but he craved success in every field of cycle racing. He wanted to be a ‘versatile’ rider, a much used and highly valued adjective in cycling parlance of the time. At a time when very few riders in Australia or the world could truly claim dominance in more than one cycling discipline, Opperman wanted it all. The opportunity for international success was still some years away. Until then, Opperman would have to be satisfied with building his reputation in Australia. Small recognised Opperman’s restlessness and together they hatched a plan to dominate road cycling across the southeastern states, while still maintaining his place on the motor-pacing circuit.

There was soon another more compelling reason for Opperman to remain in Australia. One evening, as he finished work at the Malvern Star Cycles shop, he bumped into an old school friend. But Mavys Paterson Craig was not as he remembered. The pair had been friends since school in Glen Iris. Two years her senior, Opperman had helped Mavys with her homework. They attended Sunday school together and he had been a guest at her twelfth birthday party. Although good friends, they drifted apart when Opperman left school for the public service. Now sixteen years old, Mavys had grown into a prepossessing young woman – a petite brunette with high cheekbones, grey eyes and a sweet, winsome smile. Opperman, too, had changed. He was fitter and stronger than ever, his adolescent frame having developed into a leaner, more muscular physique. She had been following Opperman’s progress in local races and admired his athleticism. He was a young man in rude health with exciting prospects. More than this, however, she was attracted to his kindness, his quiet confidence and his readiness to stick up for the vulnerable, remembering how he once gave a hiding to the school bully.12 On Glenferrie Road that evening, they were smitten and began a quiet courtship.

His budding relationship with Mavys did not diminish his desire to train or race. Nor did it deflect him for the need to travel and compete outside Victoria. In the spring of 1924, Opperman systematically targeted the biggest races around the country, making his first foray north of the border to ride the Goulburn to Sydney road race.

Established in 1902, the race had become an institution. Like its southern counterpart, the ‘Warny’, it was raced in all conditions over appalling roads. On Monday afternoon, six days before the race, Opperman and his friend and fellow professional rider, Roy Johnson, cycled north with their few belongings in a satchel or tied to their handlebars. They covered nearly 500 kilometres to Gundagai by Wednesday evening and elected to catch the train the rest of the way to have two days of complete rest before race day.

All eyes were on the two Victorian cracks who ‘aroused considerable interest’ by their journey across the border.13 In fine weather, the riders commenced the legendary 214-kilometre journey. Opperman immediately ‘displayed his powers’ by setting an infernal pace, popping the weaker riders off the back of the scratch bunch. He punctured near Moss Vale and quickly replaced the tube. Further on, near Mittagong, a piece of quartz sliced through the wall of Opperman’s tyre. He replaced the tube and used his folded handkerchief to ‘boot’ the tyre wall. Unable to remount the tyre, he enlisted the help of another rider who had given up due to repeated punctures. As he descended the ‘long hills through Bargo he tore at thrilling speed, rapidly overhauling man after man in front of him’. By Picton he was third on the road. Making time, Opperman crashed heavily while descending the twisting Razorback Road, but recovered to gain four minutes on the leader. He pedalled with such fury that observers believed ‘he would crack up before the finish’.14 But his speed remained constant. He crossed the line first and with the fastest time, some thirty minutes ahead of his nearest rival. As the sporting papers saw it, Opperman’s victory had been achieved with ‘ridiculous ease’.15

The Victorian’s decimation of New South Wales’s finest exposed the very different riding and training cultures that had evolved in each state. NSW riders tended to ride shorter distances in training and push bigger gears. In longer and hillier races, like the Goulburn to Sydney, they rode half the distance at full speed and struggled to the finish as best they could. Opperman’s higher cadence, lower gear ratios (a practice he had adopted after learning about European riding styles) and his longer training rides were ideally suited to the tough climbs and longer distance of the state’s premier race. Riders in NSW soon adjusted their equipment and training regimes in an effort to emulate Opperman’s pace.16 When Opperman won the event five years later, at the height of his powers, he did so by only seven minutes, an indication of the rising talent in the state and its more responsive approach to cycle training.

In late 1924 his life resembled that of an itinerant worker, roving across the country from race to race. In the first half of the twentieth century, it was common for professional cyclists to ride to the start of major events, even if they lived interstate. It had the advantage of maintaining or boosting their fitness and (despite the additional cost of food) it was cheaper than the train, especially when a cyclist might have to go home for a few days only to have to return a few days later.

The race schedule may have been taxing, but Opperman was living the life of his dreams. He raced, trained and travelled with riders he counted as friends. He had attained a stratospheric level of good health and fitness. ‘I couldn’t get tired’, he said, repeating a popular saying used by racers who had reached a top level of endurance.17

Opperman returned to Melbourne for more racing and a few days’ rest before his next interstate commitment. Once again, he travelled by bicycle. Heading for Adelaide, he rode until he reached Bordertown and caught the train the rest of the way to avoid the near impassable ninety-mile desert. From the city, he cycled 150 kilometres to the start of the annual Burra to Adelaide cycling race, the most important race in South Australia. He managed third fastest, but lost to fellow Victorian Percy Osborn. Following the event, he, along with Roy Johnson and Ben Ogle (recently returned from racing in France), took the train to the Victorian border, and cycled southwest toward Warrnambool for the start of the Australasian Road Championship.

The combination of touring and racing made them fitter and lighter than ever. Indeed, it became impossible to put on weight and just satisfying their prodigious appetites became a serious preoccupation. In a café in Hamilton in Western Victoria, half a day’s ride from Warrnambool, they stopped for lunch.

They each ordered a serve of steak and eggs. While they waited for their meals, they devoured a basket of buttered bread rolls and drank coffee. After their meal and a second round of bread and coffee they requested another round of steak and eggs. The proprietor only had lamp chops. ‘They’ll do’, the trio replied. Yet another round of bread and coffee was demolished while they waited. When it came time to settle the bill, the owner was agog. He explained that he had fed farmers, shearers and jackeroos, all ravenous after weeks of hard work. But he had never seen anything quite like this before. ‘It’s incredible!’ he said. Of course, to the riders this amount of sustenance was both necessary and routine. ‘Pity you don’t sell fruit and chocolate’, said Roy, ‘because we’ll need some of that for later on.’18

Despite battling rain and the Western District’s persistent winds, the trio arrived in Warrnambool in good spirits. Opperman was in the form of his life. Without concern for the main event on Saturday, he decided to race the prologue event known as the ‘Little Warrnambool’, a twenty-five-mile virtual sprint held on the Thursday before. He won. The main event, needless to say, would not be so easy.

The 1924 Warrnambool to Melbourne was initially distinguished by who wasn’t on the start line. For his third attempt at the prize Opperman was secretly pleased to learn that three-time winner, O’Shea, had recently retired from serious racing. Another notable (but altogether more sobering) absence was friend, training partner and rival Don Kirkham. He wished Oppy a good race via a telegram from the Alfred Hospital, two weeks after a motorist crashed into him as he cycled home after a race.19 The absence of these two greats created an opportunity for new talent. But far from making the task easier, it increased the desperation in the field.

As the race took shape, Opperman found himself in familiar company, riding in a small bunch comprising Jack Beasley, World War One veteran Ernie Bainbridge and newly-turned professional Jack Watson. Beasley punctured near Winchelsea, west of Geelong. His race was over. A light tail wind helped push the pace to within a few minutes of the course record set in 1909. At Werribee, the high tempo forced young Watson to fall back. The remaining duo knew each other well. Though some thirteen years his senior, Opperman worried about towing the canny and strong rider to the line. But Bainbridge was more tired than he looked. Crowds of people lined the final kilometres to the finish. Though Opperman could not detach Bainbridge from his rear wheel before the line, he was able to ‘draw away over the last few yards with a well timed sprint’.20

Opperman’s dominance of Australian road cycling was complete. Just five years since his first race along Dandenong Road with the Oakleigh West Cycling Club, he had conquered the most respected road race on the Australian circuit. At twenty, he was the youngest to ever take the Australasian title. Punters and racing officials alike were stunned by his performances. Harry Hall, President of NSW League of Wheelmen expressed what many were feeling when he declared himself ‘staggered at this lad’s wonderful speed and determination. Opperman is a human machine. He’s unnatural. A superman!’21

Victory on the road brought glory, but if Opperman was to succeed in his quest to become the most versatile rider in the country he had to return to the motor-pacing arena. There he would face his toughest opponent in a showdown that cycling fans had been talking about since the beginning of the year.

_________

1 Hubert Opperman, Pedals, Politics and People (Sydney: Haldane Publishing, 1977), p. 54.

2 David Dunstan (ed.), Victorian Icon: The Royal Exhibition Building (Melbourne: The Exhibition Trustees in association with Australian Scholarly Publishing, 1996), pp. 253–7, 363–9.

3 Daily Telegraph (Launceston), 3 March 1923.

4 Opperman, Pedals, pp. 47, 52.

5 Sporting Globe, 26 September 1923.

6 Sporting Globe, 11 October 1924.

7 West Australian, 15 October 1923; Western Argus, 16 October 1923.

8 Mercury, 15 October 1923; Brisbane Courier, 15 October 1923; World (Hobart), 15 October 1923.

9 Argus, 27 October 1923; Sporting Globe, 27 October 1923.

10 Sporting Globe, 27 October 1923.

11 Sporting Globe, 23 January 1924.

12 Recorder (South Australia), 27 November 1928.

13 The Mail, 20 September 1924.

14 Sydney Morning Herald, 22 September 1924; The Sun (Sydney), 21 September 1924; Opperman, Pedals, p. 59.

15 Sporting Globe, 29 September 1924.

16 Sporting Globe, 29 September 1924.

17 Opperman, Pedals, p. 61.

18 Opperman, Pedals, p. 61.

19 Sporting Globe, 11 October 1924.

20 Mirror, 11 October 1924; Sporting Globe, 11 October 1924.

21 Sporting Globe, 29 October 1924; Daily Telegraph, 14 October 1924.