Читать книгу Oppy - Daniel Oakman - Страница 6

ОглавлениеChapter 2

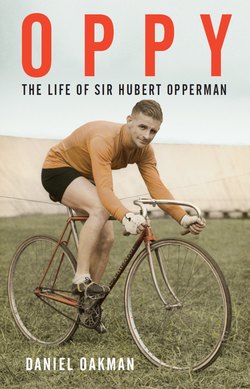

Malvern’s rising star

River Street, Richmond, Melbourne, 11 December 1918.

The blare of an alarm signalled the imminent arrival of the fire brigade. But it was too late. Shortly after 3pm toxic gases flowed into the sewer system at River Street, in the centre of Richmond’s tanning and starch manufacturing precinct.1 Edward Swannock was inside a maintenance shaft tarring the ladder when a rush of fumes from below took his breath away. Gasping for air, he fell some thirty feet to the bottom. His workmate, William Aldridge, who had been keeping guard at the entrance to the manhole, called for help at a nearby hotel. He then descended into the shaft, only to be similarly overcome. Losing his grip he too fell into the blackness.

Local tanner, John Quinn, witnessed the commotion. Unaware of the danger he immediately entered the hole and went down about twenty feet. Suddenly he was ‘stupefied by the poisonous gas’.2 His head jerked back and his arms stretched out as if gesturing for assistance. Collapsing against the ladder, a small ledge jutting out from the side of the shaft saved him ‘from falling to the black depths where the other two unfortunate men were huddled together’.3 Yet another man volunteered to descend. Samuel Mills, a tannery employee, tied a handkerchief around his mouth and head and, with a rope around his waist, was lowered down. He had only descended a few metres when he gave the signal to be hauled to the surface. Although brought up quickly he was unconscious, but alive.

Three firemen arrived at the scene. Believing that they were responding to a fire, they had not come equipped to ‘counteract the deadly sewer gas’. Walter Griffith donned a smoke respirator and ‘with this inadequate provision’ decided to go down. He reached Quinn and put a line around his waist. Then, to the horror of those on the surface, he too was overcome. His arms shot upwards as he fell back against the ledge. The workers above hauled Quinn to the surface, but it was too late, ‘some thoughtful person closed the dead man’s eyes’.

A properly equipped team finally arrived from the Eastern Hill Fire Station. Wearing smoke and fume headpieces two men climbed down and first recovered Griffith who was rushed to Melbourne Hospital. Aldridge and Swannock were then brought to the surface. Efforts to revive them proved futile.

A young boy stood among the crowd of spectators, each craning for a view. He watched as the lifeless bodies were drawn to the surface and laid gently on ground. He observed their faces, frozen in a distorted grimace. He stayed until their covered bodies were loaded onto a wagon and taken to the city morgue. The moment never left him.

* * *

Opperman, now fourteen years old, had arrived to the harrowing scene with Herald newspaper crime reporter Tom Kelynack. He had taken a temporary job at the paper while waiting to start his public service career. One of a dozen lads working at the paper – a motley crew of ‘quick witted city gamins, respectable suburban dwellers, country innocents and shrewd larrikins’ – he worked as a general dogsbody, shuttling messages, picking up results or information and running errands. After showing himself to be both quick and reliable, Opperman was assigned to Kelynack as a news spotter.4 Early in the piece, he gave Opperman the somewhat macabre, but routine, task of visiting the city hospitals and police stations to scout for news of incidents or accidents that might make for a good story. If Opperman got wind of a lead he would race back and tell Kelynack who would swing into action.

Working at the newspaper proved an exhilarating introduction to the world beyond school and the suburbs. It exposed him to the unvarnished life of the city, its tales of fatalism, cruelty and courage. It also connected the young man to other people’s daily lives as well as to great moments in history. Towards the end of 1918, Opperman was thrilled to be sworn to secrecy as the first news of an armistice in Europe came through to the newspaper, a secret made more exciting because it meant his father would soon be on his way home.

Opperman enjoyed the sense of immediacy that pervaded the newspaper, as journalists and editors rushed to meet their daily deadlines. He marvelled at the vitality of the print room, the click of the linotype, the smell of ink and the great roar as a new edition sprang from the printing presses. He thrived on the camaraderie and fraternal atmosphere, the shared purpose and the good fellowship that bound people committed to a common goal.5

After six months with the Herald, Opperman finally received notice that he would begin his public service career in the vast Postmaster-General’s Department (PMG). Responsible for postal and telegraph communications in Australia, it employed over 40,000 people across the nation. He was assigned to the Malvern Post Office, not too far from his home, and he started at the bottom, delivering telegrams and letters, clearing letter boxes, stamping and sorting mail.

To his delight, much of his work involved riding a bicycle. The standard issue postal bike, however, was a workhorse designed to give robust and reliable service over many years, rather than make the life of a postman less physically demanding. Yet, Opperman relished his time astride the sturdy machines and enjoyed the special licence granted to PMG officers to ride on the footpath and mount the kerbing. He pedalled the heavy bike up to fifty kilometres a day, six days a week. The days were long. He started at 7.30am, had a two-hour midday break, and finished with the so-called ‘goodnight’ delivery round by 7pm. The weather was irrelevant. When it was wet, he wore leather leggings and a rain cape. When it was hot, he wore a cap – and sweated.

Opperman grew fit and strong. As his body responded to the load the riding became easier. He found that he had plenty of time to daydream during his long rounds. Stories of the American frontier in Westerns or the serialised fiction of the ‘penny dreadfuls’ did not fire his imagination. Rather, he was captivated by true tales of exploration and adventure, the daring record-breaking flights by the early aviators, the physical endurance of forced military marches, or the courage of men who knew the cannonade and bayonet charges of Europe’s wars of Empire. He liked the classical legends of ancient Greece and might have distracted himself on the long delivery rounds by imagining himself a Malvern Pheidippides, running from the Battle of Marathon to Athens to announce the Greek victory over the Persian army.

As he had at the Herald, Opperman responded to the shared dedication to public service that motivated many of his post office colleagues. When an urgent telegram came in from Roma in central Queensland, Opperman raced to deliver it, reaching the recipient in around six minutes, bridging the gulf between that unimaginably remote town and suburban Melbourne to under ten minutes. With the in-house competitiveness conducted in good spirit, Opperman enjoyed the boyish camaraderie of other lads and looked forward to their fortnightly ritual of shouting each other ginger beer ‘spiders’ (a popular and delicious mix of soft drink and ice-cream).

Opperman’s fitness and willingness to push himself set him apart from the other delivery boys, who were content to get the job done by expending the least amount of energy. He dreamt of riding longer, riding further, and delivering more telegrams than the others. One Christmas Eve he volunteered to ride from the post office in Malvern to the city depot twice in a single day to collect messages that could not reach Malvern over the choked telegraph lines. On the return journey he dropped messages to the post offices at Toorak and Armadale, a few kilometres out of his way. The shift took seventeen hours and he finished at one o’clock in the morning. News of his feat spread around the post office, with a few of the older staff claiming it was impossible. Opperman’s earnestness was leavened by a cheeky irreverence. Naturally curious, if still a little shy, he routinely left his rounds late, caught up chatting with the more worldly of the post office staff. So fast had he become on pillar box clearing duties, he could leave at what would have been considered late for an ordinary rider, only to arrive precisely on time with his extra surge of speed. PMG regulations were strict, however, and he earned a fine for ‘loitering on duty’ from an egalitarian supervisor who believed that rules needed to be applied to all staff members without favour.6

For all his youthful energy, young Hubert showed sensitivity beyond his years. Just as his early years working on farms or delivering supplies to miners had been, the daily social world encountered by delivery riders was an adult one with adult concerns. As the bearer of news, he often saw people experiencing extreme emotions. In 1919, in the aftermath of the First World War, the Spanish flu epidemic tore through the staging camps in Europe as troops waited to be shipped home. Death came quickly to many of its victims, often in less than thirty-six hours. Opperman’s satchel contained condolence telegrams and, although sealed, they were instantly recognisable to the postal staff. He knew of the ‘catalytic effect’ each message would unleash once delivered. He altered his rounds accordingly, granting the recipients a few more hours of blissful ignorance before they opened the tiny envelopes of heartbreak.7

With bike racing among the most popular of competitive sports, Opperman eventually found himself in the company of racing cyclists. When his work bike broke down, he took it to the service yard and discovered that one of the PMG bicycle mechanics was none other than Harry Thomas, track hero and winner of the famed Austral Wheel Race. After his competitive career ended, Thomas helped keep a considerable fleet of cycles in good order. Opperman regularly found minor faults with his postal machine, pretexts for visits to the mechanic, who regaled him with tales of past triumphs, adjusted his handlebars and advised him on the best race posture and gear selection.8 The young lad, of course, yearned for more speed. Thomas reluctantly gave in to Opperman’s persistent request for bigger gears.

Opperman was thriving under Grandma Wil and Uncle Herb’s stable home life when Dolph returned from the war. Like thousands of other Australian soldiers who desperately wanted to serve their country, his war did not turn out to be especially notable or heroic. His periods of work as a signaller on the Western Front were punctuated by extended stays in hospital or convalescing in England. Dolph suffering variously from cystitis, influenza, mumps and lumbago.9 The trenches were havens for illness and disease, even for fit and healthy men. Dolph’s experience of war did not neatly fit into popular understandings of courageous Australia’s fighting and killing for the Empire. It almost certainly did not meet Dolph’s expectations. While he spent just weeks or perhaps several months at the front, he played no lesser part than many others and would have endured much discomfort during his years of service.

Dolph came home to Melbourne to all the pageantry that awaited returning members of the Australian Imperial Force. He resumed his regular life and rarely spoke of the war. During the emotional few weeks following his return he treated Hubert to a day out at the Australian Native’s Association Carnival at the Royal Exhibition Building and Oval, Melbourne’s premier cycling track and stadium. Before the war, Dolph had been a handy racer and was keen to introduce his son to the excitement of track racing. The towering wooden grandstands, the asphalted track, the fast pedalling bunches and the heaving crowd, all left their mark on the teenager. Dolph and Hubert pushed their way down to the fence, so they could watch riders preparing for the start of a race. They were lucky enough to see top cyclist L.C. Bowie Stevens strapping into his pedals, his arm slung over his trainer’s back for support. Opperman stared at his beautiful, athletic form and the way his pronounced quadriceps flexed in readiness for the starter’s pistol. He worried that with his feet strapped in he might fall, unaware that the binding to the cranks was essential for extra speed.

After years of separation, the bond between father and son had been renewed only soon to fade. There was no real talk of Hubert returning to live with his parents and although they stayed in touch, Dolph soon ‘reverted to type’ and drifted away to resume the quest to run his own business.10

But before he left, Dolph made one further contribution to his son’s growing interest in cycling. He brought Hubert his first proper bicycle, a Turner Model 19, which replaced the battered second-hand clunker Herb had given him so he could come home during his two-hour lunch break and avoid using public transport (use of the postal bikes outside of work duties was forbidden and their use closely monitored). The Turner was a sensible bike. Built for comfort and not for speed, it was sturdily constructed, had low gears, raked forks for a softer ride and a tourist saddle. The studded tyres, a slower but more practical choice over Melbourne’s variable road surfaces, sounded like a motorcycle to the young rider. Nevertheless, compared to the PMG bikes, it leapt from the yard, as Hubert saw it, ‘like a greyhound leaving a bulldog’. Bicycles like this were a long-term, practical investment, not an indulgence. And, at over a month’s of Opperman’s wages, he knew the expense (and possible debt) his father had incurred to secure it. Although faster than the postal bikes, it was no racer. Yet it was on this machine that Opperman fronted up to his first competition.

On a grey and wet Saturday morning in September 1919, Opperman lined up with the men of the Oakleigh West Cycling Club for their regular thirty-kilometre handicap of two laps to Dandenong and back. As a newcomer, Opperman was given a handicap of six and a half minutes ahead of the scratch men. He had dropped the handlebars and upgraded to a more streamlined Brooks leather racing saddle for the event, but still drew a mixture of raised eyebrows and quiet sympathy from his rivals. Sick with nerves, he hadn’t slept properly for days. An icy crosswind blasted from Port Phillip Bay. The incessant rain had washed a bed of red clay across the road and made existing potholes deeper and wider. Opperman ‘slithered and swung’ around the cratered surface, avoiding the rivers of slurry and broken edges where he could.11 The robust Turner took the inevitable hits well. He stayed ahead of the fast men for the first lap, but on the second he looked behind to see a dark mass of riders bearing down on him. Opperman put one last effort into the pedals. But it was in vain. The scratch group cruised past, seemingly without effort. Opperman swung in behind them. His face was immediately hit with a spray of road grit and mud spouting from their back wheels. As Opperman gasped to remain in their slipstream, he heard a sound. Aubrey Box, club champion and joker, still had enough spare lung capacity to sing ‘I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles’, his wry comment on the moist riding conditions. The pace was too hard. Opperman lost contact with the back of the group and struggled to the finish line alone and exhausted. His hopes for competitive success were crushed. To his dismay, a few men from the winning bunch came to his aid. His fierce rivals, those men who would mercilessly grind a weaker rider off their rear wheels, now laughed warmly even offering support and advice to the newcomer. They talked about the race, the terrible conditions, and how he might improve his chances.

Club members soon found their young protégé a real racing bike, an Ixion. He scrounged as much money as he could, traded the heavy roadster, and rejoiced at the lighter more nimble feel of the racing bike. Made in St Kilda and ridden by the stars of the time, the Ixion’s short-wheel base and low handlebars promised speed and agility. Naming the bicycle after a Greek god, Ixion, who was punished by being bound to a whirling and burning wheel, promised something else that the ambitious rider would have to become accustomed to: suffering. The pain and fatigue of ultra endurance riding was still unknown to Opperman and, for now, he enjoyed the intensity of short-format racing.

Opperman’s life now revolved around work, training and racing. Most days he would ride home after work, sit briefly for a hurried meal, and then head out for extra miles of training at the local velodrome or on local roads. Saturdays were the highlight of the week: race day. In the morning he cleared letter boxes, made deliveries and sorted mail. In the afternoon, he rode the eight kilometres from Malvern to Moorabbin to compete in the weekly thirty-kilometre handicap then returned to complete the ‘goodnight round’. His flair was not immediately apparent. In the 1920s, Melbourne’s cycling clubs, although depleted of many strong men due to the war, were full of talented and motivated riders. With cycling a routine mode of transport for many, many people’s general fitness level was already very high. It took time for Opperman to stand out. The handicap system (which would later impede Opperman’s chances of winning) initially helped him into lower placings. But throughout his first year of competition he did not win a single race. He was placed fourth at the Senior Cadet Championships, but struggled against older, stronger and more experienced riders. The physical nature of his job, while improving his fitness and strength, also made him tired. It was nearly impossible to arrive rested and relaxed on the start line when he had pedalled all week as well as on the morning of the event. And, like most novice racers, he overtrained. Certainly others in the club faced similar difficulties, but a postman’s lot was undoubtedly a demanding one.

Opperman fared better when he teamed up with stronger club mates. In a ‘burst of promotional enthusiasm’, the Oakleigh West Cycling Club arranged a special race day on an earth track around a local football ground. To call it an outdoor velodrome would be an overstatement, but it gave the young rider a chance to experience team racing and the loose, unpredictable and dangerous surfaces track cyclists routinely raced over. Opperman was paired with local powerhouse, Jack Beasley, a popular rider from Victoria’s western districts and a winner with the fastest time in the blue ribbon in the Warrnambool to Melbourne Classic. The contrast between the two men could not have been more pronounced, in both experience and physical presence. When the unknown Opperman lined his sixty kilogram frame alongside the 100 kilogram Beasley, he heard his partner ask for more lights so that he might see his diminutive partner in the changeovers after each lap. The genial Beasley was as surprised as everyone else at the meet when the pair won. ‘You’ll do me, mate, when we have another one of these,’ he said. Opperman basked in the validation.12

In May 1921, Opperman finally broke through. Now riding for the newly formed Malvern Cycling Club, a race against twenty-three of his club mates turned out to be a shambolic scramble for the line. In his desperation to succeed, he hit another rider’s back wheel and crashed onto the side of the road. Uninjured and with sufficient poise to quickly remount his bicycle, he sprinted furiously to regain the group, finally overhauling them in the closing kilometre.13 He won by twenty-one seconds, covering the sixteen kilometres at over thirty-five kilometres per hour.14 Although it wasn’t the graceful performance that he had hoped for, it established his reputation in the club and his confidence soared.

The biggest boost to Opperman’s speed came when he was transferred from the Malvern Post Office to the Navigation Department in town. The administrative work spared him from endless hours of pedalling and allowed him to focus specifically on his training, and, most importantly, he finished work at lunch-time on Saturdays. He raced fresh and his results started to improve. Financially, he struggled to keep his equipment in good order and pay race entry fees. After board and lodging, he had so little left over that he often had to beg for race fees to be waived against any possible winnings.

Emboldened by his club successes, Opperman now looked to enter longer professional races.15 He saved enough prize money to upgrade his bicycle to a Malvern-made ‘Glenroy’ and signed up for the Bendigo to Melbourne road race covering 147 kilometres. This was by far the longest race he had attempted and would be his introduction to the infamously punishing road surfaces of central Victoria that often determined the results of major races. Opperman defended his nine-minute head start on the scratch men until Malmsbury. As the leading men approached, he jettisoned his co-markers and tagged on to the back of the bunch. The worst roads were the long stretches of corduroy, a surface made from rounded tree-trunks laid across road and the gaps plugged with earth. The bigger riders muscled their bikes over the bone-jarring ground. The hare-like Opperman bounced his way through, and remained glued to the back wheels of the scratch men. They carved their way through the field and he contested the final sprint to finish seventh. The result was modest but it revealed something that would define the rest of this sporting career – that he seemed physiologically and mentally predisposed to endurance riding. Although still too young to understand his full potential, his results suggested that the longer and harder the race, the better he fared.

Now captivated by long races Opperman looked to capitalise on his run of good form. Two weeks after the Bendigo–Melbourne, he signed up for the Cycle Traders’ eighty-mile event. Starting in Essendon, the race followed an undulating course through the sharp hills of the gully country near Sunbury, across to Woodend, the Macedon Ranges and Gisborne. Although shorter, it would be a sterner test of his ability over some of the region’s hilliest and most treacherous terrain. It also exposed him to the backward nature of Australian cycling regulations and the truly dangerous nature of bike racing.

The Australian racing scene in the 1920s was a technological and administrative backwater. Riders were at the mercy of governing bodies dominated by men who grew up riding around the turn of the century and who stubbornly resisted the rapid technical advances in bicycle design in the first decades of the twentieth century. Riders were forbidden from using brakes – which were deemed too dangerous and encouraged inconsistent riding – and instead had to rely on back-pedalling or grabbing the top bar and pressing their forearms against their spinning legs. Freewheel hubs, which allowed riders to coast without their pedals moving around, were also prohibited. Cyclists raced in fear of horrific crashes, of flesh being torn from bone on the coarse metalled roads, or of catching deep infections that could end one’s riding career or worse. Riding under such conditions required successful cyclists to have an unhealthy disregard for personal safety and a well-developed capacity to handle fear.

As the Cycle Traders’ race got underway, a strong southerly breeze pushed the riders northwards to the much-feared Bulla Hill, near Sunbury. As they crested the rise they look down the other side to see the gravelled surface cut with a series of horizontal ridges by recent rains. The wind pushed them over the top and into a fast descent. With no brakes they travelled on to what appeared to be a ‘giant nutmeg grater’. Fear swept the bunch. Their bikes shook, slewed and bucked over the ridges. Their legs spun out of control as they attempted to slow down. Opperman gripped his bars and braced for the inevitable fall. Ashen-faced, the men reached the bottom of the descent and began to roll up the other side. Miraculously, all the riders remained upright.

When the scratch men eventually eroded Opperman’s six-minute handicap, he jumped into their slipstream as they cruised past. The hours sped by. Then they hit the Macedon Ranges with the feared climbs of the Corkscrew and the Curly Hills, and the plunge down to Woodend over corrugated unsealed tracks and corduroy roads. They powered over the course at an astounding thirty-seven kilometres per hour. All had negotiated the hills safely, except for one rider who collided with a stray cow, another common hazard when racing through Victoria’s agricultural heartland. Opperman had survived with the leading group and looked to follow Vic Browne, the strongest sprinter in the bunch. As they approached the final stage of the race, he tucked in close behind Browne’s rear wheel, using his big body to shield him from the wind. Suddenly, a car sped past the bunch only to slow down immediately once it had passed. Clouds of thick dust spiralled from the back of the car and stuck to their sweat-soaked bodies. Then, the car braked and veered violently to the side of the road, splintering the riders as they scrambled to avoid a collision. In the confusion, Browne lost his position and Jack Beasley found the front as they crossed the finish line. Charlie Shilliot came second and Opperman scraped into third place.16

Roads were rarely closed for these races. Official cars following the riders endeavoured to stop local traffic from interfering at critical junctures, but in this case a reckless motorist determined the result of the race and inadvertently set Opperman’s life on a different path.

At the finish, the new owner of Malvern Star Cycles, Bruce Small, presented a dust-plastered Opperman with his prize: a brand new bicycle. Opperman had first heard about the energetic salesman when he took fastest time in the Bruce Small Trophy, one of Small’s early attempts to build a public profile among Melbourne’s club racing scene. Malvern Star Cycles had been around for twenty years, having first opened its doors on Glenferrie Road in 1902. The proprietor Tom Finnegan had been a good track rider and, on the back of a generous handicap, won the prestigious Austral Wheel Race in 1898. He soon realised that his competitive days would soon pass and invested his winnings in the shop. A canny business operator, Finnegan secured endorsements from the best racing cyclists and capitalised on the booming bicycle trade. He also created the simple, stylish company logo, a six-pointed star that matched a tattoo on his forearm.17 When Small took over in June 1920, he wisely made few changes to Finnegan’s successful business model. His intention was to amplify them.

Small had been working as a travelling salesman for Finlay Brothers in Melbourne, returning record sales figures across the state. At twenty-five, he grew tired of making profits for others and looked to start his own business. With limited capital, he borrowed money from his mother, a Salvation Army officer, who mortgaged her home to support her son’s new venture.18 A ‘magnetic’ personality, Small (along with his brothers Ralph and Frank) built Malvern Star into the largest and most recognisable bicycle business in Australia. When he sold the enterprise in 1956, the company slogan, ‘You’d be better on a Malvern Star’, had been seared into the memories of a generation, the result of one of the most audacious and expansive marketing campaigns in Australian history.

Opperman was drawn to Small’s charisma, confidence and knowledge. Their business relationship commenced almost immediately, when Small invited Opperman to ride for Malvern Star. At the time, it was a gamble. He knew little of Opperman’s pedigree, but he wanted to build a stable of high-profile athletes to ride his bicycles to victory. Small offered Opperman a new racing machine in exchange for the Glenroy and he would sell the prize bike in the shop. Small’s confidence in the young prospect was soon rewarded. Opperman won his first championship sash three weeks later at the Senior Cadet’s Cycling Championship in Melbourne.19 Importantly, Small was already connected to some of the biggest names in cycling. Opperman gained easy access to some of the best cyclists in the country, including riders who had raced overseas.

Cyclists who returned from Europe came back transformed. The intensity of racing on the Continent improved a rider’s physical power and mental capacity to endure long, arduous races. It also took their knowledge of training methods, nutrition and race-craft to levels simply unachievable in Australia. Yet, these athletes were men of action, and not inclined to record or speak in depth about their experiences. The only way for an ambitious cyclist to learn from these masters was to ride with them.

One such titan was Donald Kirkham. Lauded as one of the greatest road cyclists in the world, pictures of Kirkham’s fabulous legs had been appearing in newspaper and journals since before the First World War.20 Along with his teammate Snowy Munro, Kirkham was the first Australia to ride in the Tour de France. In 1914 he completed the 5380-kilometre journey and managed to come seventeenth against the best in the world. He also held unpaced records and was a winner of the gruelling Melbourne six-day event with another cycling hero Bob Spears. A farm boy from the Victorian pastoral plains of Carrum, Kirkham was tall and angular, with a soldier’s bearing. A man of ‘temperate habits’, when he wasn’t riding he disappeared into the crowd. On the bike he ‘epitomised rhythm’ and possessed a seemingly indefatigable power, able to finish epic rides in the same composed and efficient manner that he had started them.

Small sent Opperman to train with Kirkham in 1922, hoping for a rapid transfer of knowledge from the legend to the protégé.21 Kirkham taught Opperman how to manoeuvre safely within the bunch, how to seek out shelter from behind bigger riders and how to avoid rapid changes of pace when taking his turn on the front. Kirkham schooled Opperman in sprinting over unstable roads, picking the best lines through rough or muddy surfaces. He also taught him useful tricks such as how to use a pothole in the road to dislodge a rider who was ‘sitting on’ (drafting in his slipstream) by suddenly forcing them to slow down and face the wind. Opperman greedily absorbed all of Kirkham’s experience. This gave him an immeasurable advantage over his rivals and accelerated his development.

The most important advice Kirkham gave Opperman was not about racing at all. It was not intended to sound trite, but when he explained that ‘you are never as tired as you think you are’ he neatly captured a truism of athletic performance; that the greatest barrier to success would not be the strength of his muscles, but the power of his mind.22 Although the idea of being able to push through the deepest tiredness was still an abstract concept to the young rider, this lesson from one of the country’s most experienced riders would later help him overcome the most desperate psychological battles with exhaustion and fatigue.

A quiet pioneer of elite cycling in Australia, Kirkham died in tragic circumstances. Knocked down by a drunken motorist during a race in 1926, his thighbone was shattered. Worse still, after he was struck he had been left wet and exhausted by the roadside and contracted pleurisy. The disease lingered and led to his premature death in 1930. He was forty-four years old. For the close-knit cycling community, it was a sobering reminder of how dangerous road racing could be for even the toughest of men.23

Just as the people he mixed with were utterly absorbed with cycling and bike racing, Opperman, too, had been undergoing his own transformation. The simple act of riding, when exploring new roads on a training ride or even while racing, nurtured his sense of wonder at the world around him, opening ‘vistas of interest’ with time to ‘study and ponder’. The bicycle not only extended the distances he could travel and the speeds he could achieve, it had become an extension of his self and ‘represented as much as [his] heart or oxygen’. When riding he became a fusion of blood, flesh and steel. In this cybernetic state, he felt more energetic, more capable and more alive. The bicycle, he said, had become a ‘basic element for living’, indistinguishable from other physical or mental needs.24

Throughout 1922 Opperman juggled his full-time job and a demanding schedule of races. Increasingly, he started to think about the possibilities of a life completely dedicated to riding and racing bicycles. In addition to the hours of training he needed to undertake, more prosaic matters started to intrude on the delicate balance he had struck between working and competing. Opperman rode as a professional and as his victories amassed so too did his winnings. The conditions of employment in the public service required that additional income be declared, for fear that any external source of finance might compromise a government employee’s impartiality. For a time Opperman was forced to engage in the charade that he raced only for trophies. But as Opperman’s name (in addition to his prize winnings) began to appear more frequently in the newspapers, the subterfuge became difficult to maintain. In November, he reached a crossroads.

One of the more prestigious (and well-paid) races on the professional circuit was the Launceston to Hobart. When Opperman’s boss denied him leave to compete, Bruce Small suggested that he quit and join Malvern Star. He would be expected to earn his salary in the shop, but he would be given time to train and any race winnings would be his to keep. It was time to decide between accepting a more modest cycling career within the confines of his secure job and exploring his full athletic potential with the backing of Small’s emerging business. His heart knew the answer. But he feared that Grandma Wil might not be supportive. He told Small he would talk it over with her before making a decision.

At first, Wil resisted her grandson’s impassioned arguments. After all, she had watched her own hard-working son roam across the country trying to sustain his small enterprises with varying degrees of success. Now, her grandson was proposing to give up a reliable and safe career for a life racing bicycles, working in a still emerging small business run by a man she had never met. The astute Wil also knew that the life of a racing cyclist could be a fickle one. Beyond the glamour of the podium, professional cycling exposed young men to danger, drugs, and a cast of nefarious characters looking to involve vulnerable young riders in gambling, corruption and race fixing.

She refused to give her blessing until she had met Mr Small. Luckily when Wil and Bruce eventually met they got along famously. Small was at his self-assured and charming best and promised to nurture, and not exploit, young Hubert’s great talent. Wil was also impressed by the twenty-six-year-old’s business acumen and his prediction that bicycles would continue to be popular, even as more cars began appearing on Melbourne’s roads. This wasn’t just another marketing pitch for him to put over an old lady. You could see it on the streets and read about it in the papers. Motor vehicles were still the preserve of the rich with less than one in ten people owning a car in the early 1920s. Bicycles – not cars – still inspired wild enthusiasm both as a symbol of human potential and as a device that might revive a generation exhausted by war.

The First World War re-energised popular fondness for the bicycle and its role in developing the ‘national physique’. Social reformers, religious leaders, suffragists and eugenicists all embraced bicycles as a conduit to a more vital, healthy and disciplined lifestyle. Exercise, toned muscles, rising heart rates and expanding chests all created a palpable sense that the bike was indeed the technological marvel that humanity had been waiting for. The bicycle ‘puts new vigour into the human frame’, claimed the Adelaide Mail, ‘and from the very urgent need of health in these strenuous times [is] all the more important to humanity’.25

Beyond any talk of a golden age of bicycle retailing, Small’s proposed weekly salary of three pounds ten shillings (fifty percent more than Opperman’s public service pay packet) helped dispel any lingering reservations Wil may have had. To allay his own anxiety about leaving the security of the public service, Opperman negotiated twelve months of unpaid leave during which time he could return to his old job should things not go to plan. Shortly after, he steamed across Bass Strait to contest his first interstate event, the 190-kilometre Launceston to Hobart, then the richest and most respected cycle race in Tasmania.

At a time when more conventionally strong men with large, powerful bodies won long bike races, the Tasmanian press doubted the prospects of the slightly built Victorian. Some noted his solid performance in the Warrnambool to Melbourne, yet the truth was his rivals did not see him coming. He started from what was called ‘virtual scratch’ (a modest handicap of nine minutes), but gave nearly an hour away to the lower graded riders. The day was fine and sunny, the roads in good condition. He narrowly avoided a field of tacks that had been ‘scattered freely’ over the road outside of Launceston by a road-race hating ‘malefactor’.26 He dropped his co-marker after sixteen kilometres and ‘mowed down a strong field’.27 Twenty miles from the finish, Opperman punctured. His prospects looked bleak until a young boy, riding in the opposite direction, saw the rider in difficulty and offered him his bicycle. Opperman jumped on the undersized bike and either stood in the saddle or sat and rode bandy-legged to complete the race. Confusion about how many laps the finishers were required to ride of the Newtown sports field spoiled the finish, but Opperman’s fourth place with fastest time was undisputed. The Tasmanian press were stunned. ‘It seemed almost incredible that such a youth should achieve the distinction’, exclaimed the Examiner.28

In an article titled ‘A wonderful lad’ the Mercury became the first newspaper to recognise that Australian cycling fans might be witnessing the emergence of a special, maybe even exceptional, talent:

Looking at Opperman, who made fastest time, one marvelled at the fact that such a slim, spare young man possessed the stamina and energy for a contest such as a great road race. Only eighteen years of age, he is merely skin, bone, and muscle, but what there is of him is sound, and his performance will be long remembered.29

Unprepared for the attention, Opperman posed for the cameras but spoke haltingly to the press. His shyness, born of modesty and inexperience, made him appear somewhat aloof. He had yet to develop the easy rapport with journalists that would become a defining feature of his celebrity. The dramatic race and the sheer unlikelihood of Opperman’s speed over such a long distance, started sports writers and fans talking about the Victorian’s future prospects. For all he gained, he also lost an important advantage for any competitor. While not yet a national figure, Opperman would never race with the element of surprise again.

_________

1 Age, 12 December 1918; Age, 17 December 1918.

2 Age, 12 December 1918.

3 Australasian, 14 December 1918.

4 Hubert Opperman, Pedals, Politics and People (Sydney: Haldane Publishing, 1977), pp. 17–18.

5 Opperman, Pedals, p. 19.

6 Opperman, Pedals, p. 24.

7 Opperman, Pedals, p. 19.

8 Sporting Globe, 15 November 1922.

9 Service Record, NAA: B2455, ADOLPHUS SAMUEL FERDINAND OPPERMANN.

10 Opperman, Pedals, p. 26.

11 Opperman, Pedals, p. 29.

12 Opperman, Pedals, p. 32.

13 Opperman, Pedals, p.31.

14 Prahran Telegraph, 21 May 1921.

15 Age, 5 September 1921.

16 Argus, 3 October 1921.

17 See Rolf Lunsmann’s webpage: http://bicyclehistory.com.au/MalvernStar/

18 Opperman, Pedals, p. 35

19 Argus, 24 October 1921.

20 The Lone Hand, 1 February 1913.

21 Opperman, Pedals, p. 42.

22 Opperman, Pedals, p. 43.

23 Sunday Times (Perth), 18 May 1930.

24 Opperman, Pedals, pp. 19, 46.

25 Mail (Adelaide), 8 May 1915.

26 Daily Telegraph (Launceston), 6 November 1922.

27 Referee, 29 July 1931.

28 Examiner, 6 November 1922.

29 Mercury, 6 November 1922.