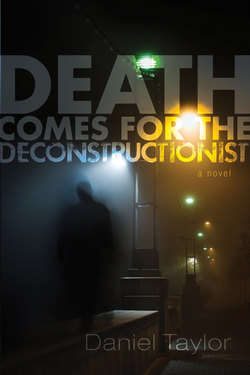

Читать книгу Death Comes for the Deconstructionist - Daniel Taylor - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

SIX

ОглавлениеThe next day I go down to the Minneapolis police headquarters between Fourth and Fifth streets to introduce myself to Detective Wilson, the lead detective on the case. The headquarters are in city hall, which looks appropriately authoritative, like a cross between a grand French chateau and the witch’s fortress in The Wizard of Oz. Mrs. Pratt called Detective Wilson after our meeting to let him know about me, and it has had the effect I expected. When I appear in his office he looks at me like a father looks at a biker picking up his daughter for a first date.

“I may as well tell you right out that I don’t like this.”

“I understand.”

“But Mrs. Pratt has the right to hire whoever she wants.”

“Yes.”

“As long as that person doesn’t get in the way of the investigation.”

“Of course.”

“Or break any laws.”

“I understand.”

“Including laws of privacy and search and seizure.”

“Of course.”

“You are not a cop, and I don’t want you playing cop. If you leave anyone with even the faintest impression that you are an officer or in any way connected to the official investigation …”

“You’ll have no problem …”

“I will charge your ass.”

“… with me.”

“And if you should by absolute random luck come across anything—and I mean anything—I want to hear about it before your next breath.”

He pauses, standing behind his desk, leaning forward on his knuckles.

“Do I make myself clear.”

“As a bell.” Cliché answering cliché. Judy would be proud.

“Is there any more I can do for you, Mr. Mote?”

This normally would be my cue for a mumbled exit line and a quick departure. I stand up to do just that when I see something in a plastic bag on top of a stack of papers on the edge of Wilson’s desk that makes my heart jump. It looks like a knife, but I instantly know it isn’t a knife—I know what it is instead.

“What is that?”

long time no see

Wilson looks where I’m pointing and snorts. He takes the bag and drops it into a drawer.

“That’s none of your business, that’s what it is.”

“It’s the murder weapon, isn’t it?”

Suddenly Wilson is keenly interested.

“And how would you know that, Mr. Mote?”

“I’ve seen it before.”

Now Wilson is more than interested; he’s riveted.

“That is indeed the weapon Dr. Pratt was attacked with. But the public doesn’t know that. We disclosed that Dr. Pratt was stabbed, but we didn’t describe the weapon. We let people assume it was a knife, so we could distinguish a false confession from a true one. Mrs. Pratt doesn’t even know. If you’ve seen it before, Mr. Mote, then I think perhaps I should read you your Miranda rights.”

It isn’t a knife. It’s a gold letter opener. The blade is narrow, about nine inches long. But it’s the handle that’s distinctive. It’s a whale. In fact, it’s Moby Dick. Its golden head and body form the handle, and the blade of the opener comes out its tail.

I know the murder weapon, and I know it’s Moby Dick because years ago Pratt pulled it out of his briefcase one day as class was beginning. He held it up for all to see and performed one of his sixty-second, spontaneous tours de force that left you amazed—at how brilliant he was and how brilliant you weren’t.

“This letter opener, students, is a perfect exemplum of the derivative and allusive nature of all that we so innocently call ‘reality.’ It purports to be an opener of letters. Simple enough. But it has a whale for a handle. And not just any whale. This whale is Moby Dick, of literary fame. How do I know this is Moby Dick? Because I bought it myself at Melville’s home in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. No whale within a hundred miles of Pittsfield can be any other than Moby Dick. Not in the mind of the purveyor of the whale, nor in the mind of the viewer. History and biography and culture have colluded to equate Pittsfield with Melville and Melville with whale and whale with Moby Dick.

“But of course this is not a whale at all. It’s a piece of cheap pot metal, painted gold. It is merely an iconographic representation of a whale. And it’s certainly not the specific whale Moby Dick. Not only because a whale is flesh and blood and this whale is metal and paint, but because the whale Moby Dick never existed in time and space. Moby Dick never got wet, never ate a squid, never did any whaley things, because it existed only in the mind of Herman Melville. And Melville turned that mental Moby Dick into little black squiggles on a white piece of paper. And those little alphabetic symbols arbitrarily suggest to us ‘whale,’ a highly improbable creature most people have never actually seen with their own eyes but that they are nonetheless certain exists.

“So, this whale-handled letter opener is really a symbol of a symbol of a symbol, the grounds of which were electrochemical discharges in Melville’s brain—whoever Melville was (as if we could ever really know). And that’s not even to mention the person who decided to manipulate this symbol for profit, making this tawdry little curio for bookish tourists, most of whom read novels with the naiveté of children—capitalism again reducing everything it touches to quid pro quo, simplifying the playful complexities of art to the periodic elements of dollars and cents.”

See what I mean? Pratt took your black-and-white, monochromatic world and gave you back a kaleidoscope of colorful, if fleeting, connections. And you thought it was a simple letter opener. Ha!

Seeing the letter opener now, I feel more grief for Dr. Pratt than I had even at the time of his death. Symbol of a symbol of a symbol? Perhaps, but also sharp enough to have made a very effective hole in you, sir—the revenge of simple materiality over all things theoretical.

I give Detective Wilson the short version of all this, assuring him that hundreds of people had seen that letter opener over the years in Pratt’s classes. I can’t tell whether he believes me or not, but he doesn’t read me my rights. He settles for a simple threat.

“You shouldn’t have seen that. If I hear anywhere that the murder weapon was other than a knife, I will know that you are the source of that information and I will charge you with obstructing the investigation. Understand?”

I assure him that I do. And I remember Pratt’s words that day in class as he put the letter opener back in his briefcase.

“I always carry this with me to remind myself that everything we experience is actually a quotation of something else—something only slightly less unreal. And also to fend off attacks from my rival critics!”

We all laughed then, but now it doesn’t seem so funny.

we think its hilarious