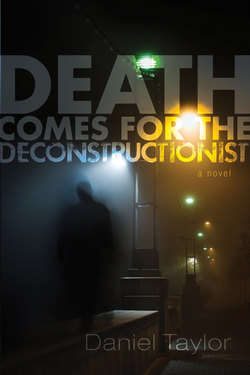

Читать книгу Death Comes for the Deconstructionist - Daniel Taylor - Страница 5

ONE

ОглавлениеSomething is wrong.

I’m not well. The voices are back.

I apologize. That’s a bleak way to start. And too confessional. The world doesn’t need another Underground Man or daddy-killing poet. Everyone these days is confessing everything, which leaves no space for genuinely confessing anything. Confession requires a standard, an agreed-upon line that has been crossed. It requires “ought” and “I’m sorry” and “Forgive me” and “I will not do that again.” Not for us. We confess and absolve ourselves in the same breath. “I did it. I wouldn’t change anything. It’s who I am.” To quote that great mariner-philosopher Popeye, “I yam what I yam.” Self-absolving confession. How efficient. Cuts out the middleman.

Of course I’m referring to someone you’ve likely never heard of—Popeye. A cartoon character from the 1930s and beyond. How can I make myself understood, for God’s sake, to people who don’t share the same shards of pop culture that I have shored against my ruins? (Name the poet just alluded to. It’s an easy one.)

Here I go again. I have to calm myself. My mind starts rolling downhill and it gathers neither moss nor meaning (Rolling Stones). Faster and faster (“Like a complete unknown / Like a rolling stone”). It’s not six degrees of separation for me, it’s no degrees (Sly and the Family Stone). Everything is connected—directly and remorselessly—to everything else. At the same time, nothing is connected to anything. Monism (all is one) hooks up with solipsism (one is all), and I am their bastard child.

And you have no idea what I’m talking about. And neither do I. But I do not apologize. After all, “I yam what I yam.”

And the “I yam” that I am playing at the moment is detective. It’s what Mrs. Pratt thinks of me, so it is what, for a time, I will be. Her husband is dead, found on the street below his thirteenth floor hotel room, a hole in his chest and a pool of blood spread nimbus-like around his head.

I like that—“nimbus-like.” It just came to me this very moment. One of those synapse-leaping connections. A nimbus is a stylized halo in medieval art—which is the first thing I thought of—but also a kind of cloud, and an encryption algorithm and a Danish motorcycle and more than one literary magazine and, of course, a flying broom. And if he were alive, Dr. Pratt could make connections among all these things. Because that was his gift—making connections between things no one else would ever think to connect. And it left your head spinning.

I know because I was once a student of Dr. Pratt’s. He was, for a time, a kind of intellectual saint to me—nimbus and all. And he certainly left my head spinning.

Dr. Pratt has been dead since spring, almost six months now, and his wife has just called me. I tell her, indirectly as usual, that she is wasting her time. I’m not a cop, or a criminal investigator, or any kind of detective. (The only thing I’m good at detecting are my own deficiencies, at which I am a master—a talent I share with my soon-to-be ex-wife.)

I’m actually nothing official, almost officially nothing. You might say I’m a researcher, with an emphasis on searcher. I search. I look into things. I don’t probe people—or even events. I collect information. And then I try to make something out of it—a kind of artist of found data, you might say (think Duchamp and urinals). I try to burrow new tunnels through old hordes of information. I marry scattered facts to see if I can turn data into knowledge. (I had once hoped to turn knowledge into wisdom, but Dr. Pratt cured me of that.)

I’ve been a searcher all my life, but I started getting paid for it by this lawyer I know. He needed someone to interrogate the Tet Offensive in order to establish a post-traumatic shock defense for Vietnam vets. I was out of work and knew how to use a library. Since then I’ve become an expert on Legionnaires’ disease, universal joints (General Motors and Toyota, not Ford), tempered glass, emotional stress in flight controllers and junior high social studies teachers, recidivism rates for women car thieves, bite rates for Chows, flow rates for dams, and insurance rates for epileptics. And expert on a thousand other things I wish I didn’t know. My mind is clogged with a million bits of information, not one byte of which gives me a good reason to get up in the morning.

My job is not the kind that shows up on those career tests they give you. I took one in high school and they told me I was suited to be a forest ranger. The possibility had never entered my mind, but it was kind of nice knowing there was a niche for me somewhere, if I ever really needed it. You know, say I was fifty and things weren’t going real well. I could maybe show up at a fire lookout tower in some forest somewhere and sort of casually bring up this test I took thirty years back and just see if I hit it off with the rangers like the test said I would. To tell the truth, I’ve found myself thinking of the woods lately. Lovely woods, dark and deep.

Anyway, I’ve been working for lawyers off and on, and Dr. Pratt’s widow somehow finds out about it. I’d gotten to know her a little when I was a graduate student. You see, Pratt was my advisor as well as my professor. And guru and model and, you could say, nemesis. Mrs. Pratt was young then—thirty-something. I liked her. Okay, maybe I even had a crush on her. She was good-looking and friendly, two things you didn’t see a lot among faculty wives. Most of them seemed kind of worn and faintly bitter. Too many years living with men whose first love is books.

Anyway, the phone rings, and it’s Mrs. Pratt. I know of course about Dr. Pratt’s murder. In fact, I had heard him speak downtown at the Midwest Modern Language Association convention only a few hours before he was killed. I went to hear him for old times’ sake. I had even planned to look him up afterward to see if he remembered me. To tell the truth, I’d been a little nervous about it.

When I tell Mrs. Pratt on the phone that I had heard her husband’s talk that night, she seems disconcerted. Says it’s eerie—that’s her word—eerie that I heard him speak just before he died. It doesn’t seem eerie to me—hundreds of people heard him speak just before he died. Dying after speaking isn’t any stranger than dying after eating or dying after washing the car. It always comes after something, you know what I mean?

I tell Mrs. Pratt that I’m not a private investigator or anything like one, that I am extremely unlikely to solve the crime, and that the police will only see me as a nuisance. But she insists I “look it over.” She says she doesn’t expect me to find the killer. She just wants more information.

“I just feel like there’s something there to be seen that the police wouldn’t recognize if they tripped over it. I think you can help.”

It’s a new concept for me. To be thought capable of helping, by a woman no less. I let the idea roll around in my psyche for a moment. I’m sure it’s the main reason I say I’ll think about it, even though the ache in my stomach makes me immediately wish I hadn’t.