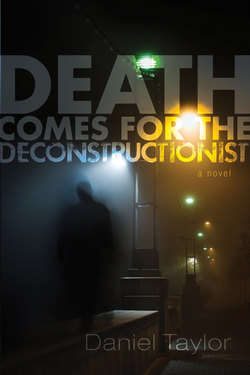

Читать книгу Death Comes for the Deconstructionist - Daniel Taylor - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

EIGHT

ОглавлениеAfter the blowback from driving by our old house, it’s several days before I’m myself again. Then again, what does that mean, “I’m myself”? Which “myself” is the real one? What is a “self” anyway?

Where’s Pratt when you need a good deconstruction?

oh thats right hes dead end of self

I remember him quoting a warning from another Melville novel once, something about being careful about seeking self-knowledge, you may mistake yourself for someone else. I know I have. I mean, I’m pretty sure there’s more than one of me. My wife said so. And Uncle Lester before her.

me and my shadow strolling down the avenue

But don’t we all have multiple versions of ourselves? Private self, public self, self for the spouse, self for the boss, self for our friends at the pub. And we don’t always get to choose which one to be at a given moment. At least I don’t. Sometimes life seems to assign me a self and there’s not a lot I can do about it. Other times, more than one self shows up.

Like when Uncle Lester caught me and a neighbor boy playing with a ouija board a year or two after Judy and I had moved in with him. Lester ran the kid out of the house and then turned on me, his head full of Leviticus. He unbuckled his belt as he walked toward me, saying something about me being cut off for consulting with mediums and spirits. He liked that phrase, “cut off.” He used it a lot. And it was always him doing the cutting and me on the receiving end.

This time he was madder than usual.

“You have contaminated my house. You have brought powers and principalities into my very home. You have turned a godly house into a place for demons. You are possessed of evil spirits. You will be cut off.”

I was petrified. I knew it was true. I knew what it felt like to have something else sharing my mind. I was unclean and deserved to be cut off. I even determined to take the whipping without flinching. But when I saw the horrible look on his face as he reached for me, I ran.

He caught me by the back of my shirt. I let my legs go limp so as to fall onto the floor and shrink into the smallest possible target, but he lifted me by the shirt and started whipping me with his belt. Usually I could get away after three or four licks, but this time he had a good hold. He just kept hitting me, over and over. I thought that he might kill me this time. Part of me was attracted to the idea.

Then, suddenly, there were no more licks, and he dropped me to the floor. I slid away and looked back. Judy had grabbed his right arm and wouldn’t let it go. He was yelling and cursing at her.

“Don’t think I won’t whip you too, you little idiot. Let go of my arm, goddamn you.”

But Judy wouldn’t let go. She had her eyes closed tight and her lips were moving silently. I didn’t stay to see what happened next. I ran out the front door and didn’t come back until late in the night.

thats right run run wee cowrin timrous beastie let your sister take the heat save your own sorry ass

Living with Uncle Lester was like living in a Kafka novel. Not that I’d heard of Kafka, of course. But when I discovered him later, I knew how his characters felt. The world is full of rules, but it’s never clear exactly what they are or how to keep them. Some of Uncle Lester’s rules were easy enough: “Don’t smoke, don’t drink, don’t chew—and don’t go with girls who do.” But others were amorphous and hazy, like “have the mind of Christ,” “be godly,” and “show thyself approved.” And then there were the rules that couldn’t be found in the Bible, but that were all the more powerful for being unstated.

I had the distinct feeling I was playing (and losing) a game in which only the umpires know all the rules. Sometimes you learned about a rule only after you’d broken it. Uncle Lester was the umpire in his house—an official representative of the Big Umpire Upstairs—and forgiveness came at the end of a belt, if it came at all.