Читать книгу Recollections of an Unsuccessful Seaman - Dave Creamer - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

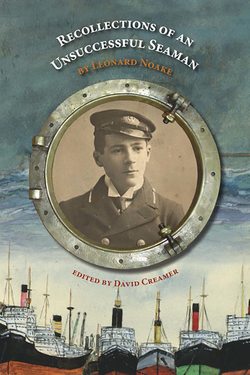

THE THIRD MATE

ОглавлениеWhen we got ashore after that torpedoing business, the old chief officer told me that he was finished with the sea and that he would sooner sweep the streets than go through all that again. You can imagine my surprise therefore when I joined another of the company’s vessels as second mate a fortnight later to find the old chief officer on board. It’s a great pity the poor chap didn’t stick to his decision, for he lost his life on the following voyage. British seamen being in short supply, we take on a deck crew of Malays and some Arab firemen.

To save money, our manager tries taking advantage of the shortage of certified mercantile marine officers by sailing without a third officer. He’s hoping the chief officer and I will do double the work for the same meagre wages, all in the name of patriotism, but I tell him I would see him in Hell first. It would be impossible for us to maintain the vigilant lookout that is absolutely necessary in wartime on board a 5,000-ton ship with a Malay deck crew, and with the mate and me working 12-hour watches every day. The manager would have sacked me on the spot if he had dared, but as it was he found a third officer, a young fellow 73 years of age, who was as strange a character as you would ever wish to meet.

Arriving from New York, where he had had some job in the Customs, he tried to ‘join up’, but was too drunk at the recruiting office to be favourably received, although he had four sons in France and was as hardy as any young soldier aged 20. He decided to stay at a hotel in Cardiff courting Mother Booze and the barmaid until his locker was empty. ‘I may be getting on in years,’ he said to me on joining the ship, ‘but there’s not so many who can stand on their heads when they’re over 70!’ He promptly stood on his head to prove the point and took five shillings off me before returning to the pub.

On this voyage to Halifax, Nova Scotia, we keep close to the Welsh and Irish shores and right under the shadow of the beautiful cliffs and caves around Mizen Head, where the sweet scent of the wet turf is wafted seaward. The third officer keeps himself busy in his spare time on the 12-day passage with his hobby of ‘laundry work’. His cabin is festooned with yellowish rags that were once his clothes, but are now too far gone and tatty for the poor old chap to expose to the public view. At sea he wears homemade white canvas trousers and socks upon which he has sewn patches.

We arrive at Halifax in the early morning and commence loading some of the few thousand tons of flour we are to take to France. As often happened, by the time evening came the old third mate, whose cabin is opposite mine, has had many imaginary visitors to see him.

‘Good evening, Captain!’

‘Oh good evening, do come in and have a drink,’ he would reply to himself. A glass would chink, and then he would ramble on to his imaginary old shipmates about strange happenings and past voyages when he had been master of Nova Scotia schooners and brigs in the Spanish and South American dried fish trade. He would speak of shipwrecks and mutinies in which his wife, who had borne him 11 children, had taken an active part. He remembered the schooners Rose Marie and the San Juan; the brig Modiste, abandoned at sea; and the Mystery, which was lost by fire. His body is scarred by make-believe wounds from bullet and knife. Poor old chap – I liked to listen to his stories because sometimes I imagined I might just be hearing the truth. He went ashore later that night; the police brought him back to the ship just before we sailed. He seemed quite unconcerned, smoking his vile old pipe and totally out of his mind.

The cargo being loaded and the hatches battened down, a gang of naval ratings work for a couple of days making chocks and then securing the four 80-foot motor launches we load on deck. These are the M. L. Boats,i ‘Joy Yachts’ or ‘Petrol Punishers’ as they are nicknamed. About 550 of these boats were built, mostly in Canada and Bayonne in New Brunswick, but they were not particularly successful because their petrol consumption was around 50 gallons per hour for a speed of 19 knots. Not only that, they were very costly to build, had insufficient beam for their length, and lacked any strength in a seaway. I know a little about their construction because I later lived on and looked after one of these launches that had been converted into a yacht.

We leave Halifax shortly before a terrific explosionii in the harbour. Our destroyer escort is picked up 200 miles west of the Scilly Isles but lost an hour later in thick fog, only to next be seen inside Portsmouth harbour. The French ports being too congested to receive more ships, we lie at anchor for ten days in the Solent before finally crossing the Channel and discharging our cargo of flour in Calais. We are then sent back to Cardiff for bunkers.

The shipping company manager hasn’t forgotten me. I am informed that an ‘older servant’ of the company is here to relieve me and that he has agreed to sail without a third officer. Good luck to him; unfortunately the ship was sunk on her next voyage, so I wasn’t too sorry to be out of it. The last I saw of the old third mate was in the pub shortly after he had discharged himself from the ship. ‘They may get an older man than me,’ he told me, ‘but by God they won’t find one tougher!’