Читать книгу Recollections of an Unsuccessful Seaman - Dave Creamer - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ABOUT THE BOOK, THE AUTHOR, AND THE EDITOR

ОглавлениеTHE BOOK

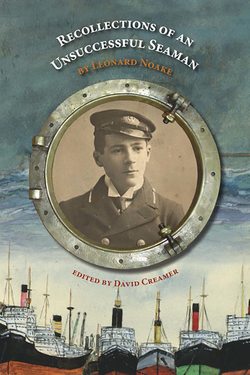

The original manuscript is typed and liberally illustrated with detailed pen and ink drawings, exquisite watercolour sketches, black-and-white photographs, and the occasional picture postcard. The 235 numbered pages have been professionally bound in leather with the front cover inscribed in gold lettering with the title, Recollections of an Unsuccessful Seaman. For some obscure reason the author’s name, George Leonard (Len) Noake, is not included.

The book was written in 1928–1929 whilst Len, who was terminally ill with tuberculosis, alternated between being nursed at his home in Southwick, Sussex, and the Swandean Isolation Hospital in Worthing, where he was to pass away at the age of 42 on 21 November 1929. It will never be known whether he had the satisfaction of seeing his completed work in book form, or whether it was bound after his death.

Len’s wife, Mabel, was to outlive her husband by over 40 years until her death in 1970. Their daughter Anitra, the youngest of three children, discovered her father’s book in the loft of the family home in Lewes, Sussex, whilst sorting through her late mother’s possessions. Unbelievably, its existence had never been disclosed by Mabel who was, according to Anitra, a very private and unassuming lady who shared very few stories or memories of Len with their children.

The book suffered from water damage in 2001 when Anitra’s home, also in Lewes, was flooded. The water-based paint used in many of the sketches ran, causing the colours to become smudged and blotched and the leather cover was irreparably damaged; over time, some pages have become faded and stained. The book was rebound in 2016 in a new leather cover. Thankfully, the manuscript itself remained legible, and some of the author’s skilled artistic efforts, carefully reproduced using modern scanning and colour enhancing techniques, are unaffected. Their survival ensures that Len’s work will be recognised as a true and unpretentious insight into life in the mercantile marine almost 90 years ago.

THE AUTHOR

George Leonard Noake, or Len, as his family and friends always called him, was born in Worcester on 25 September 1887. Little is known of his childhood; his father, Charles Noake, was a Lloyd’s Bank inspector, and records show the family to be living in Birmingham when Len commenced his pre-sea training on board the nautical training establishment HMS Conway in February 1903.

On completion of his pre-sea training in July 1905, Len served an apprenticeship until 1908, but details, once again, are sparse. In the book he writes that he fell 40 feet from aloft during this period; on the basis of this statement, I have assumed that his early seagoing career was ‘under sail’, and that he fell from the rigging of a sailing vessel in which he was serving. He also mentions having visited South America prior to his voyage on a tanker in 1918. Since his detailed memoirs begin in 1908, and there is no record of him sailing to South America between 1908 and 1918, it can also be assumed that this earlier visit occurred during his three-year apprenticeship. The reason behind him choosing not to include this period in his recollections remains a frustrating mystery – it may have been that he hadn’t kept a log for his early voyages, or perhaps he chose to ignore, or forgot, his first years at sea. Likewise, he chooses not to share details with the reader of his working on a farm in Devon between 1913 and 1915, or his courtship with Mabel prior to their wartime marriage in November 1916.

Len was clearly a lively but proud and responsible person, fond of a tipple, and blessed with a great self-belief that he would get by, though not necessarily prosper, in his chosen career. He was never out of work for too long despite the depression and hard times in the shipping industry. His financially disastrous ventures into farming and road haulage show him to have been a gullible yet hard-working and very determined individual, as does the writing of his recollections during a time when he quite clearly knew he was terminally ill.

As with all professions where the breadwinner has to spend lengthy periods away from his or her family, there is a fine line to be drawn between abandonment and support. In this respect, Len had difficult and heart-rending decisions to make, but his later work on coasting vessels, where he was closer to home, suggest his young family was never too far away from his immediate thoughts. It must be remembered that voyages of between six and 12 months were considered the norm in the period of his writing. His claims not to have been a ‘Bolshie’ ring a little untrue; his opinion of ship owners borders upon outright vilification. The last chapter in his book suggests he retained his fervent attitudes and militancy to the very end.

I would have considered it an immense honour to have met Len, my great-uncle. Editing and researching his memoirs has given me a very clear insight into his distinctive humour, and also an appreciation of his cheerful personality and resolute character. I find it hard to believe that he should be so demeaning as to think of himself as an ‘unsuccessful seaman’.

THE EDITOR

Little did my mother realise that returning home sometime in the 1990s, after visiting her first cousin Anitra, with a leather-bound book written by my great-uncle would start a project that has kept me occupied, on and off, for many years. As a master mariner myself, I was fascinated by the book. Here was an unpublished account of seafaring life in the early 1900s that included enthralling stories of foreign ports, of being torpedoed during the First World War, and of the hardships and suffering experienced by the men of the mercantile marine during the worldwide shipping depression of the 1920s. I felt it almost my duty to make the book available to a readership far wider than our immediate family and friends. Over the next few months, I transcribed the entire manuscript, word for word, spelling mistake for spelling mistake, into a file in my computer, where it remained unopened but not completely forgotten for a considerable period of time.

In 2005, I belatedly made my acquaintance with Anitra and her own family in Lewes. During my visit, I sought Anitra’s permission to try to publish her father’s work. She was enthusiastic, delighted that someone else was appreciating and recognising her father’s efforts. She insisted upon me taking the water-damaged book back home so that I would be able to work on it at my leisure. It was with a greatest sadness that I learnt of her passing in April 2007.

The original manuscript had little hope of being accepted for publication; political correctness and changes in the English language over nearly 90 years have rendered some of the original manuscript unprintable. I was reassured by publishers that by editing my great-uncle’s work, I would not be detracting from his literary efforts, and that the original unpublished and unedited manuscript would remain in the family’s possession as a priceless heirloom of sentimental value.

Editing and researching Len’s fascinating recollections has not been easy. Every effort has been made to portray and reproduce the original manuscript as it was written, but in many instances it has been necessary to shuffle words and sentences to enable the story to flow in a more logical sequence. I will also admit to having used ‘editor’s licence’ in making my own very occasional interpretation of what I think Len intended to write when some of his sentences were found to be totally confused or disjointed. It is for this reason that some original paragraphs and the final chapter, set out for easy identification, have been included within the manuscript to allow the reader to understand the author’s style of writing. It is difficult to comprehend how someone so very ill and weak could sit behind a typewriter and, from memory and possibly a journal, write and illustrate a story of such compelling interest and detail.

My research into his career and the names of the ships in which he served would not have been possible without the Liverpool Maritime Museum, Southampton City Council Archives, and the Toronto University, which accepted responsibility for the safekeeping of our national maritime archives when, a few years ago, the British Government inexplicably decided to dispose of most of the country’s seafaring records.

David Creamer, 2017