Читать книгу Recollections of an Unsuccessful Seaman - Dave Creamer - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

INTRODUCTION

ОглавлениеMan that is born of woman has but a short time to live,

He comes in like a maintops staysail, and goes out like a flying jib.

R. F. W. Rees, The Second Matei

Here I am, admitted to a public sanatorium and hospital with all the symptoms of an excessive intake of liquid refreshments and with consumption of the lungs. This is my reward for spending the last 20 years being one of those misguided persons going down to the sea in ships to occupy their ‘labahs’ upon the great ‘watahs’.

This Swandean Hospitalii in Worthing for incurable consumptives is about as cheerful as the mouth of the Elbe in a north-east gale on a winter’s night. I have lain in bed for months not feeling very well; they have been expecting me to die for some time, but one cannot keep all one’s appointments, not to time anyway. I feel sorry for some of the poor chaps here; those who are not actually dying seem, for the most part, to be far too ill to have a good yarn. I should have died a long time ago, several times in fact. Whilst sailing as an apprentice I fell 40 feet from aloft, and followed this up with rheumatic fever and scurvy. When I left the West African trade, a kindly German doctor gave me just 12 months to live. Then there was the ship I failed to join, which was lost with all hands, and the big tramp steamer that disappeared the voyage after I had been paid off. I also came very close to bleeding to death from head injuries after being attacked by some robbers in a lonely part of the docks in a French port. Yes, I am sure you will be sorry for me when you learn that I have been a great sufferer from bad heads, despite them generally occurring after either imbibing too much internal liniment or incurring severe financial cramp.

They seem woefully behind the times in this public sanatorium and hospital, with the doctors appearing to know no more than I do about treating tuberculosis. The young nurses don’t like being told they couldn’t cure a kipper, never mind a patient, and yet the old saying goes that all the nice girls love a sailor! There is no modern apparatus, no X-rays, artificial sunrays, or any other rays for that matter. They do have an excellent stock of fresh air, a bottle of cough mixture, and a flask of cascara sagrada, but that just about sums up their stock in trade. Instead of giving oxygen to a man on his last gasp, they should give him Sanatogeniii much earlier and then the deaths might be fewer. You hear far too much of this ‘fresh air’ business; no one could get much more of it than I have by sailing across the North Sea for a couple of years, but it hasn’t done me any good.

I am now able to sit on a deckchair on the lawn and keep a lookout on the high fence that shuts us off very completely from the outside world. I can walk up and down the narrow strip of grass as if it were an imaginary ship’s bridge and even talk to an imaginary helmsman, but I am tired of these occupations. I’ve read every book in the place, even The Constant Nymphiv which shows just how desperate one can become. I have found scientific books about atoms and electrons to be all very wonderful, but they’re only for the improvement of trade or machine and not for us humans. The nearest approach to a cure for this complaint is all about money and being able to take advantage of what it will buy rather than science. I recently paid nine pence for a book entitled How to Cure Tuberculosis, but to no real benefit other than to the bookseller’s pocket.

I’ve also had better food for 14 shillings a week in a coasting steamer than I’ve had in this place. I am sure you have seen those Indian fakir fellows, or photographs of them. We all appear exactly the same, just skin and bones. My legs look like an optical illusion with my thighs no thicker than an ordinary man’s forearm, and as for my calves! For most of the patients, however, these sanatoriums are a godsend and they are infinitely better off in hospital than they would be in their own homes. It just needs someone in high authority to run around with a flannel hammer and to tap the brains of those in charge to wake them up before they get into a groove.

There is no amusement provided for the patients unless the parson’s weekly visits should count, but I’m sure they’re not intended as such! He is quite a nice man the parson, but another sufferer. He suffers from the truly ghastly complaint of speaking with a very parsonical voice, even in ordinary conversation: ‘My poor fellow, you are not looking yourself today.’ That cheers me up no end until I reach for the mirror. And then he continues, ‘I will now read to you from the Scriptyahs,’ which reminds me of George, a steward aboard a little coasting boat in which I was sailing as chief mate. George also had a parsonical voice; he would come creeping into my cabin the morning after the night before with the greeting ‘blessed are the weak for they shall be comforted’, before sharing the glass of whisky or bottle of beer he had brought with him as a means of providing the further comfort we both sought.

As I’ve said before, there is nothing to do in the hospital to keep one amused. Needlework on cushion covers doesn’t appeal to me, and I lose my wool mending my socks. I’ll have to fall back on my old logbook and live in the past. A rolling stone may not collect much moss, but it can collect an awful lot of memories. After months of monotony one feels one simply must break out somehow, so I am going to break out by writing my recollections, even if they should be as rambling as I have been these past few months. The only really sensible thing I can remember doing is getting married,v although I suppose you will say the next sensible thing will be my getting buried. I can give no details about that for the moment; medical opinion suggests it won’t be too long.

Recalling my life will not be easy, but there will be one or two good features in the book at least!

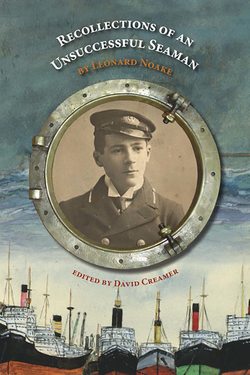

This beautiful art plate of the author comes free with the book.

Yours truly,

The unsuccessful seaman