Читать книгу Ringside Seat to a Revolution - David Dorado Romo - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеpanopticon, a prison in which every single inmate

was under 24-hour surveillance. Foucault argued that

these 18th-century blueprints for a surveillance

machine marked a turning point in the history of the

world and the “economy of power.” The panopticon

is the kind of historical detail you can easily grow an

entire philosophical system out of.

Call it delusions of grandeur, but that is exactly

the kind of detail I was searching for myself—some-

thing that would open up an entire city or era to our

understanding, something with metahistorical, who

knows…even metaphysical implications.

Then again, I would have been happy if I could

just find Pancho Villa.

I FOLLOWED EVERY clue I could, no matter how

insignificant, that might help me find Villa in El Paso

or Juárez.

I wanted to know about Villa’s eating habits: he

loved canned asparagus and could eat a pound of

peanut brittle at a time.

I wanted to know where his offices and headquar-

ters were: the Mills Building, the Toltec and the First

National Bank in El Paso. In Juárez, his headquarters

were in the Customhouse and on Lerdo Street.

How much money he had in the bank on this

side of the line: $2,000,000.

What kind of jewelry his wife wore to high-toned

Sunset Heights tea parties: five diamond rings, a dou-

ble-chained gold necklace with a gold watch and

diamond-studded locket attached, a brooch, a comb

set and earrings with brilliants.

Villa’s musical tastes: he enjoyed “El Corrido de

Tierra Blanca,” “La Marcha de Zacatecas,” “La Adelita”

and “La Cucaracha.”

I TRAVELED THROUGHOUT the United States

and Mexico in pursuit of Pancho Villa. I flew to the

National Archives in College Park, Maryland, where

among other things I pored through the daily reports

of a secret agent in El Paso and examined the 1916

blueprints for the Santa Fe Bridge delousing plant

(where they say Pancho Villa sparked the Bath Riots).

I pursued Villa at the Getty Research Institute in

Los Angeles, a very exclusive place, where thin, pale-

skinned archivists watch your every move closely and

you must always wear white gloves. (How did

Pancho ever end up here?) There I hunted for the

photograph of Ambrose Bierce in El Paso, the old

gringo writer who crossed the border into Juárez in

1914 to join Pancho Villa. “Ah, to be a Gringo in

Mexico—that’s euthanasia!” he wrote a few days

before crossing and was never heard from again. The

photograph, apparently, had also disappeared; it had

been misplaced somehow in the archival collection.

At the Casasola Collection in Pachuca, Mexico,

images of El Paso, Juárez and Villa were everywhere.

There were traces of Villa in Mexico City, in Lubbock,

Texas, and at the Smithsonian Archival Center in

Washington, D.C. Pancho’s letters to Hugh Scott when

Scott was stationed at Fort Bliss were at the Library of

Congress. Reports of his activities were in the munic-

ipal archives of Guerrero, Chihuahua (where one of

the janitors gave me the keys to a closet full of dusty

boxes going back to the 1840s). Clues about Villa

were in Bisbee, Austin, New York, at the Quinta Luz

in Chihuahua, at La Bufa in Zacatecas. There were

even some traces of Villa at the National Library of

Medicine in Bethesda, Maryland, where there were

documents showing that, for the United States, track-

ing down Pancho Villa and tracking down Mexican

germs had become parallel pursuits.

PANCHO VILLA TOOK me to places where I

never expected to go. But although Villa is every-

where in this book, it’s ultimately not about him. He’s

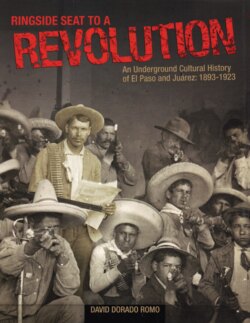

merely my tour guide. Instead Ringside Seat to a

Revolution is about an offbeat collection of individuals

who were in El Paso and Juárez during the revolution.

Many of them crossed Pancho Villa’s path at one time

or another. More often than not, they were both spec-

tators and active participants during one of the most

fascinating periods in the area’s history.

This book is about insurrection from the point of

view of those who official histories have considered

peripheral to the main events—military band musi-

cians who played Verdi operas during executions in

Juárez; filmmakers who came to the border to make

silent flics called The Greaser’s Revenge and Guns and

Greasers; female bullfighters; anarchists; poets; secret

service agents whose job it was to hang out in every

bar on both sides of the line; jazz musicians on

Avenida Juárez during Prohibition when Villa tried to

capture Juárez for a third time; spies with Graflexes;

Anglo pool hustlers reborn as postcard salesmen;

Chinese illegal aliens; radical feminists; arms smugglers;

and, of course, revolutionaries, counterrevolutionaries

and counter-counterrevolutionaries. Ringside Seat to a

Revolution is as much about cultural fermentation as

it is about revolution. It’s about a renaissance born of

conflict.

10