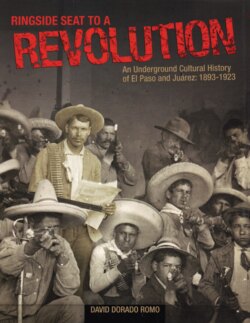

Читать книгу Ringside Seat to a Revolution - David Dorado Romo - Страница 23

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление18

But I guess I shouldn’t be too irritated by Metz’ take on things. Historians are like the

blind men who touched different parts of the elephant and thought it was either a wall,

a snake, a tree trunk or a rope, depending on what they touched. We all have our biases

and our limited viewpoints. It all depends on where we stand. Microhistorians, I think, are

just a little more honest about it. We tend to believe that there is no such thing as a defin-

itive History—only a series of microhistories.

Because I can’t fit the whole elephant into this book, all I can do is share with you

the part that I can perceive.

EL PASO PROBABLY had more Spanish-language newspapers

per capita during the turn of the century than any other city in the

United States. Between 1890 and 1925, there were more than 40

Spanish-language newspapers published in El Paso. They provided

a counternarrative of the border not found in the mainstream press

on either side of the line. These periodicals printed not only news

and political manifestoes but serial novels, poetry, essays and other

literary works as well. The cultural milieu created by a large inflow

of political refugees and exiles—which included some of Mexico’s

best journalists and writers—set the stage for a renaissance of

Spanish-language journalism and literature never before seen in the

history of the border. The first novel of the revolution, Los de Abajo,

was published in serial form in 1915 in the Spanish-language daily,

El Paso del Norte. Mariano Azuela, a former Villista doctor, wrote it

while he lived in the Segundo Barrio.

These Spanish-language newspapers, even when they didn’t

deal with politics or literature, served as a voice for the ethnic

Mexican community in El Paso that usually didn’t see itself reflected

in the Anglo press. They carried ads for Mexican-run businesses on

both sides of the line—for grocery stores owned by Mexican mer-

chants or pharmacies that sold natural medicinal herbs from

Mexico. They published classifieds seeking musicians for a

Mexican orchestra. The readers could be updated on the latest gossip about the man who

paid 200 pesos ($100 in U.S. dollars) for a kiss as part of a neighborhood fundraiser. They

could also tear out a ballot to elect the local Mexican American beauty queen.

Yet politics was indeed most of these publications’ bread and butter. Because they

were published on the American side of the border, the Spanish-language press could be

aggressively anti-Díaz. Many of them were openly revolutionary. Victor L. Ochoa, the first

El Pasoan to lead a rebellion against the government of Porfirio Díaz in 1893, was the edi-

tor of El Hispano Americano.

In 1896, Teresita Urrea was listed as the coeditor with Lauro

Aguirre of El Independiente. She had moved to El Paso that year and was already called

the “Mexican Joan of Arc” because of the various uprisings her name had inspired

throughout northern Mexico. In 1907, Aguirre’s press also printed La Voz de la Mujer. It

was a fiery, aggressive weekly, which called itself “El Semanario de Combate,” written and

edited by women who had no qualms about denouncing their political enemies as

“eunuchs” and “castrados” (castrated men).5 Those epithets were particularly insulting to

Spanish-language newspapers

in El Paso carried ads that

catered to the needs of the

ethnic Mexican community

on the border. This turn-of-the-

century advertisement in

Lauro Aguirre’s Reforma

Social lists both medicinal

herbs from Mexico and

French drugs that were on

sale at a Mexican-owned

pharmacy on Stanton Street.

(El Paso Public Library.)

5

La Voz de la Mujer, July 28, 1907, Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley.