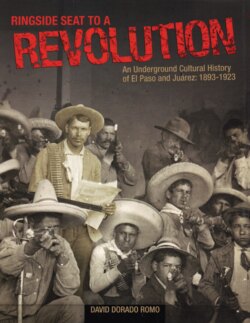

Читать книгу Ringside Seat to a Revolution - David Dorado Romo - Страница 38

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеNEWSPAPERS IN MEXICO, for the most part,

suppressed the news of the Tomóchic massacre.

When it made the front pages in El Paso, the Mexican

government tried to censor U.S. coverage of the mas-

sacre. Even though Victor L. Ochoa’s newspaper was

published on the American side of the line, pressure

by Mexican officials forced it to shut down.

“I was then the editor of a daily newspaper in El

Paso, Texas—El Hispano-Americano— whose circula-

tion was largely on Mexican soil,” Ochoa told the

New York Times:

I heard with horror of the massacre of my

friends and published the facts. The paper

was excluded from Mexico, and my con-

stituents forced to give it up. Merchants who

advertised in it were compelled by the

authorities to boycott me…The soldiers mas-

sacred the whole population…Imagine my

horror at this. My own family had fallen vic-

tims to the relentless cruelty of the [Díaz gov-

ernment]. This, too, I published. My paper

soon succumbed for its lack of support. I

gathered all I had, and, turning all my effects

into cash, threw the money into the fund for

my people’s liberation.59

Ochoa’s newspaper wasn’t the only local publi-

cation that was banned from Mexico. The El Paso

Times, under the editorial direction of Juan Hart, was

also prohibited from crossing south of the border

after it published a manifesto put out by an armed

group of revolutionists that, according to the newspa-

per, was led by several Tomóchic survivors.60 They

had attacked the border customhouse in Palomas,

Chihuahua on November 1893, shouting “Remember

Tomóchic!”61 The Mexican government tried to por-

tray them as just a bunch of ruffians and bandits. But

the revolutionary document that the El Paso Times

published showed that the raiders in fact did have a

political agenda.

The rebel manifesto was very similar to the Plan

de Tomóchic. It too condemned the Mexican presi-

dent for the Tomóchic massacre, the suppression of a

free press and the imprisonment of writers who criti-

cized the government. It called for the principle of no

reelection, which would prohibit future Mexican pres-

idents from serving more than one term.62 It also

denounced the economic concessions the govern-

ment of Porfirio Díaz made to U.S. capitalists. Díaz,

the manifesto proclaimed, had “mortgaged Mexico on

the foreign market. His mode of selling his country to

foreigners is criminally censurable.”63

In retaliation for publishing articles sympathetic

to the rebels, the Mexican government threatened to

imprison any Mexican businessman who advertised

in either El Hispano-Americano or the El Paso Times.

One pro-Díaz newspaper in Mexico City was upset at

the amount of coverage the fronterizo newspapers

gave the insurrection along the U.S.-Mexico border.

“Not only the [El Paso] Times, but the other opposi-

tion papers, are at present printing more Mexican

news, via the United States, than ever before in their

history,” Las Dos Repúblicas complained.64 The gov-

ernment of Porfirio Díaz claimed these publications

were fanning the flames of revolution. The govern-

ment was right.

IN THE WINTER of 1893, Victor Ochoa became

the first Mexican American to launch a revolutionary

movement from El Paso. He was ahead of his time in

more ways than one.

Even the name of his newspaper, El Hispano-

Americano, had a modern ring to it. The term

Hispano Americano, or Hispanic American, was

rarely used by fronterizos around the turn of the cen-

tury.65 El Pasoans with Mexican ancestry, even those

born in the United States, were usually just called

33

VICTOR L. OCHOA: EL PASO’S FIRST REVOLUTIONIST

59

New York Times, August 17, 1895.

60

This was probably inaccurate. Most historical accounts don’t mention any survivors of the Tomóchic massacre.

61

“Revolution! Los Tomochics Attack the Custom House at Palomas,” El Paso Times, November 10, 1893; El Paso Times, November 9, 1893.

The revolutionists captured 800 pounds of ammunition, carbines, arms, supplies as well as $300 cash.

62

El Paso Times, December 3, 1893.

63

Ibid.

64

El Paso Times, December 21, 1893.

65

The term “Hispanic American” was, however, gaining some acceptance during the 1890s among some fronterizos. The Alianza Hispano-American

was founded in 1894 and there was also a Congreso Literario Hispanoamericano in 1892 to commemorate the “discovery” of the Americas.