Читать книгу Ringside Seat to a Revolution - David Dorado Romo - Страница 37

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеthat they’re capable of changing the route of an entire

solar system with their gravitational force.”54 It exhor-

ed its readers towards political unity using the example

of atomic theory and the greater force subatomic parti-

cles possess when they are united. A section of the

publication also examined the phenomenon of astral

projection.

But the underlying motif of Aguirre’s metaphysical-

cal-revolutionary book was that Teresita, with her

extraordinary lightness of being, was the only woman

capable of taking Mexico to a higher spiritual plane.

Revolution, for Aguirre, was a collective form of

astral projection.

IN THE SUMMER of 1892,

Lauro joined Teresita and 12

members of the Urrea fami-

ly in Nogales, Arizona,

after Porfirio Díaz had

forced Teresita into

exile. Immediately,

Aguirre began publish-

ing El Independiente

from there. He found-

ed the newspaper

together with Richard

Johnson, an American

radical, and Manuel

Flores Chapa, a Mexican

revolutionary who had for-

merly collaborated with

Catarino Garza’s rebellion car-

ried out by a group that called

itself “libres fronterizos” (free

bordermen) in South Texas.

The news of the massacre

of Tomóchic in October 1892

radicalized Lauro Aguirre. It

spurred him to call for armed

insurrection. Before this, like the Tomóchic villagers

themselves, he had believed in taking up arms only in

self-defense. After the massacre, Aguirre changed his

mind. He now believed that both offense and defense

were necessary in the struggle against Díaz. Like Cruz

Chávez, the leader of the Tomóchic rebels, he had for-

merly opposed the killing of his enemies once they

were disarmed. Now, he saw things differently. “The

Mexican authorities are thieves and assassins,” Aguirre

wrote in a letter to a Teresista rebel after the massacre.

“Show no compassion towards them. They show none

towards us.”55

In early 1893, Aguirre met with a group of people

at the Urrea home to draft a revolutionary manifesto

called “El Plan de Tomóchic.”56 The manifesto

denounced the massacre of Tomóchic as well as the

war of extermination that the Mexican government was

waging against the Yaqui Indians. It accused the feder-

al army of murdering thousands of innocent Yaqui

men, women and children and selling those who had

survived into slavery. It called for the restora-

tion of the Liberal Constitution of 1857,

which guaranteed the freedom of

press and religion. One of the

Plan de Tomóchic’s clauses—

that was very uncommon

for its time and place—

demanded absolute

equality before the

law for both men and

women. The mani-

festo was for the

abolishment of “all

laws or social prac-

tices that maintains

inequality based on

gender, race, nationali-

ty or class.” It called for

new legislation “declar-

ing both men and women,

whites and blacks, natives

and foreigners, rich and poor,

have the same rights, duties

and privileges and that they be

absolutely equal before the

law.”57 Finally, the Plan de

Tomóchic, called for an armed

revolution against the “the

tyranny of Porfirio Díaz.”

Nine men and seven women signed the Plan de

Tomóchic including Teresita’s faithful companion,

Mariana Avendaño.58 Neither Teresita, Lauro Aguirre or

Tomás Urrea signed the document due to heavy gov-

ernment surveillance. Arizona agents hired by

Chihuahuan governor Miguel Ahumada, however,

reported that these three were the Plan de Tomóchic’s

true authors.

32

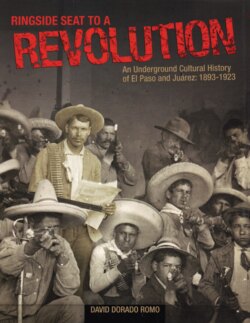

Teresita, her father Tomás, her stepmother Gabriela

(holding the baby) and her siblings, ca. 1896.

Photograph by J. Burges. (Southwest Collection,

Texas Tech University.)

54

Aguirre and Urrea, Tomóchic, p. 128.

55

Osorio, Tomóchic en llamas, p. 193.

56

It was also called the “Plan for the Restoration of the Reformist Constitution.”

57

The Teresista plan is included in its entirety in Osorio’s Tomóchic en Llamas, pp. 397-389.

58

One of the signatures—that of Tomás Esceverri—may have been Don Tomás’ pseudonym. His wife’s maiden name was Esceverri.