Читать книгу Ringside Seat to a Revolution - David Dorado Romo - Страница 27

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеthe United States and Mexico and a major center for

smelting, cattle, mining and other products of

binational trade. City boosters claimed El Paso’s

geographic location made it “the best pass across

the Continental Divide between the equator and the

North Pole.”15 It was one of the fastest growing cities

in the Southwest and had a population—according to

the 1896 El Paso City Directory—of 15,568. About

60% of the inhabitants were of Mexican descent;

although they were not officially segregated, most of

the El Paso Mexicans lived in an area south of

Overland Street.

For the next few

decades, its rail-

22

road connections

and the concentra-

tion of Mexican

residents would

make El Paso an

ideal location

from which to plot

a revolution.

The Chinese

Exclusion Act of

1882 had trans-

formed El Paso

into a major cross-

ing point for illegal

Chinese immigra-

tion into the

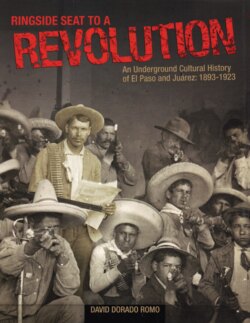

Listening to McGinty Band concerts at San Jacinto Plaza

on weekends was a popular form of entertainment for

United States. A

large number of

the city’s court

cases were either

related to Chinese

immigration or to the local opium trade. Most of the

individuals charged with maintaining “a disorderly

house”—the codeword for opium dens—almost

invariably lived in Chinatown. (Other popular crimes

in 1896, judging from the local police records, were

sexual crimes—fornication and adultery—which

would usually end up costing the violator $50 or sev-

El Pasoans during the turn of the century, 1896.

(El Paso County Historical Society.)

eral days in jail.)

A less risky form of recreation at the time was

taking strolls to San Jacinto Plaza on weekends to

hear city-sponsored McGinty Band concerts. One his-

torian described the McGinty Band as “a group of

musicians and beer drinkers who hauled countless

kegs of El Paso beer and provided many hours of

entertainment for fellow El Pasoans.”16 It was the

same musical group that had played while the cloud-

seeding experiment took place on the Franklin

mountains that year. Scientific American magazine

sponsored the experiment to ascertain whether or not

it would rain if cannon balls were shot into the clouds.17

El Pasoans could also attend musical and theatri-

cal performances at the Myar Opera House, the most

prestigious stage in town. On October 15, 1896,

Teresita Urrea took a rest from performing miracles to

sing and play the gui-

tar for guests at her

birthday celebration.

That same evening,

the Myar Opera

House scheduled a

different kind of mira-

cle—the screening of

the first silent movies

ever shown in the

city. But the first

screening fell through

because the Vitascope

projector only worked

on direct current;

only alternating cur-

rent was available in

the city. When the

moving pictures were

finally shown a week

later, the audience

was greatly amused

by the scenes of a

man kissing a big-

chinned woman named May Irvin; a bicycle parade;

a bathing scene; and two “negroes” stereotypically

enjoying their watermelon—a scene which, accord-

ing to the El Paso Herald, brought great guffaws from

the crowd. There was also a moving clip shown that

evening that was only described in the evening pro-

gram as a “lynching scene celebration.”18

For the more active types, bicycle races were very

popular. In 1896, El Paso’s Euro American women

were still talking about Annie Londonderry’s stopover

in the city a couple of years before as part of her 15-

month bicycle trip around the world. The women

were shocked and harshly critical of Londonderry for

15

El Paso Chamber of Commerce. Prosperity and Opportunities in El Paso and El Paso’s Territory for the Investor-Manufacturer-Jobber-Miner-

Farmer-Home Seeker.

16

Frank Mangan, El Paso in Pictures, p.41.

17

Conrey Bryson, Down Went McGinty: El Paso in the Wonderful Nineties.

18

Willivaldo Delgadillo and Maribel Limongi, La Mirada Desenterrada, p. 175.