Читать книгу Ringside Seat to a Revolution - David Dorado Romo - Страница 29

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChurch and because she denounced the priests for

charging money to the poor for performing their reli-

gious rites, Teresita provoked the ire of Padre Manuel

Castelo, the Tomóchic parish priest. He called

Teresita’s words and healings the work of the Devil.

Castelo threatened to excommunicate every

Tomóchic villager who believed in her. The villagers,

enraged by the threats, beat up the priest and ran him

out of town. They took control of the church build-

ing and began holding their own religious services.

When the local authorities tried to intervene, the

Tomochitecos declared

they would obey no civil

authority who violated their

religious beliefs. The

Mexican federal authorities

were called in to put the

rebellious villagers in their

place. Things got out of

hand quickly. What started

off as a local religious

squabble flared up into a

fierce battle between the

villagers and the federal

soldiers. Porfirio Díaz was

afraid that if news of the

uprising reached the world

press, foreign investment in

Mexico would suffer. The

president sent a telegram to

the governor of Chihuahua

ordering that as soon as the

Tomóchic rebels were

“apprehended, they should

be quickly and severely

punished.”22 The governor

understood this to mean the complete extermination

of the inhabitants of Tomóchic.

The greatly outnumbered villagers of Tomóchic

held the soldiers of Porfirio Díaz off for two weeks.

Their war cry was “Long live the great power of God

and the Saint of Cabora!” The Tomochitecos nearly

defeated the government troops, thanks to the rebels’

superior marksmanship, Winchester repeating rifles

and their courage inspired by the belief that Teresita

would make them impenetrable to bullets. Less than

100 fighting Tomochitecos killed more than 600 gov-

ernment soldiers. The Teresista rebels ran out of food,

water and ammunition but kept fighting even after

the federals set the village on fire. The federals cap-

tured seven rebels alive, including Cruz Chávez.

These rebels were placed against the wall and execut-

ed immediately. As punishment for the uprising, the

Díaz troops allowed the dead bodies of the fallen

Tomochitecos to rot out in the streets for days.23

Tomóchic immediately became a symbol of pop-

ular resistance against the Mexican government. It

would be a thorn in the side of the Porfirio Díaz

regime for years to come. Even 20 years later,

Maderista insurrectos took heart in the memory that

one Tomóchic rebel was

worth ten federal soldiers.

THE FIRST WEEK that

Teresita was in El Paso, she

saw about 250 patients a

day. She took male patients

in the morning and women

and children in the after-

noon. “She never charged

for her services,” the El Paso

Herald wrote. “If a rich

patron donated money to

her, she would distribute it

among the poor.”24

Newsmen reported vari-

ous healings among her

patients. One journalist saw

Teresita cure a man whose

swollen jaw “diminished

from the size of a football to

that of a baseball.”25 The El

Paso Herald wrote that

Captain Isaiah Weston visit-

ed Teresita because his left

arm had been hanging limp for days. When he came

out of her room, Weston said he was healed. George

Peck, “a well-known newspaper reporter,” claimed

Teresita healed him of the crippling effects of a para-

lytic stroke. The El Paso Herald added that on the

same day of the healings, Teresita predicted rain with-

in 12 hours, even though there were no clouds in the

sky. Four hours later, it rained.26

Unlike the evening paper, the El Paso Times was

not impressed by Teresita’s powers. The morning

daily compared her to Francis Schlatter, a half-crazed

faith healer from Denver traveling through the

Southwest that same year who claimed to be divine.

22

Telegram from Porfirio Díaz to Rafael Izabal, December 28, 1921, published in Osorio’s Tomóchic en llamas, p. 267.

23

See Francisco Almada’s La rebelión de Tomóchic en Chihuahua.

24

El Paso Herald, July 1, 1896.

25

El Paso Herald, September 23, 1896.

26

El Paso Times, June 18, 1896.

24

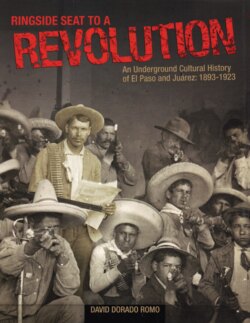

A José Guadalupe Posada print showing

the martyrdom of La Santa de Cabora.

(Gaceta Callejera, 1893.)