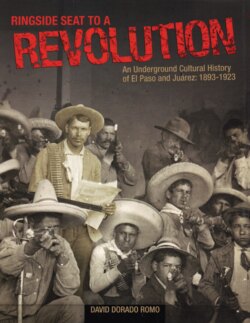

Читать книгу Ringside Seat to a Revolution - David Dorado Romo - Страница 28

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление23

having the audacity to wear bloomers during her bike

trip. These women belonged to the Christian

Temperance Union, which had been organized to try

to rid the town of its 25 saloons.

It was difficult for women in turn-of-the-century

El Paso to break out of the strict societal roles

reserved for them. In 1896 El Paso female school

teachers were not allowed to get married, drink,

smoke or be seen in public after 9 p.m. City leaders

designated a five-block zone

south of Utah Street (today’s

Mesa Avenue) as the

“Reservation.” It served to seg-

regate not Indians, but “women

of ill repute.” Alternative sexual

lifestyles for women were, of

course, completely out of the

question. On September 29,

1896—the same month Teresita

would get in trouble with the

authorities for her alleged revo-

lutionary activities—the El Paso

Times reported that “the police

were on the lookout for a

woman who was masquerading

on the streets in men’s clothes.

She was first noticed eating in a

restaurant.”19

TERESITA ALSO DID not

exactly fit current notions of a

woman’s place in society on

either side of the border. A

woman of many contradictions,

she defied all the reigning

stereotypes of a nineteenth-century mujer mexicana.

Newspaper ad announcing El Paso’s first

movie screening at the Myar Opera House.

(El Paso Times,

October 15, 1896.)

She was the illegitimate daughter of a rich

Sonoran hacendado, Don Tomás Urrea. Her mother,

Cayetana Chávez, was a poor Tahueco—part Cahita,

part Tarahumara Indian—woman who had once been

employed as Don Tomás’ maid. Don Tomás impreg-

nated Cayetana when she was 14 years old.

Teresita dedicated her life to healing the poor.

One observer claimed that more than 200,000 people

had visited her home in Rancho Cabora, Sonora; she

had healed 50,000 of them. Most of them couldn’t

afford a physician. Yet she intermingled comfortably

with high society on both sides of the border,

although she had practically no formal schooling.

Later in life, she even won a New York beauty con-

test. According to her half-sister, Anita Treviño Urrea,

that was one of Teresita’s proudest moments.

The masses considered her a saint, yet many

would stop believing her after she married, divorced

and later cohabited with an Anglo man. He was sev-

eral years younger than her. She bore him two daugh-

ters out of wedlock. The Catholic church considered

her a heretic, the Spiritualists considered here too tra-

ditional in her religious

views, and the Mexican

government considered

her a dangerous subversive.

She was opposed to the

spilling of blood, yet the

rallying cry “Viva Santa

Teresa” was heard during

several uprisings through-

out northern Mexico.

According to a Mexican

official quoted by the New

York Times, Teresita was

responsible for the death

of more than 1,000 people

killed during those upris-

ings. At 19, Teresita was

forced into exile by

President Porfirio Díaz.

She crossed the border

into the United States in

1892, the year that the sol-

diers of Porfirio Díaz mas-

sacred and burned down

the entire village of

Tomochic.

FOR MORE THAN two weeks in October 1892,

1,200 federal troops laid siege to Tomóchic, a small

Chihuahuan village about two hundred miles south of

El Paso.20 The trouble began a year before, when the

charismatic leader of the village, Cruz Chávez, kicked

the local priest out of town. Chávez was the leader of

a spiritual movement inspired by the miraculous heal-

ings of Teresita.21 (Reminiscent of the modern day

Pentecostals, Chávez “spoke in tongues” during his

religious services.) The Tomochitecos made pilgrim-

ages to Rancho Cabora to pay homage to the young

woman, be healed by her, and ask for her advice.

Because Teresita believed that God’s healing could

manifest itself without the mediation of the Catholic

19

El Paso Times, September 30, 1896.

20

The most complete accounts of the battle of Tomóchic are Rubén Osorio’s Tomóchic en llamas and Paul Vanderwood’s The Power of God Against

the Guns of Government: Religious Upheaval in Mexico at the Turn of the Nineteenth Century.

21

Cruz Chávez’ son, Cruz Chávez Méndias, would later become a colonel in Pancho Villa’s army.