Читать книгу Ringside Seat to a Revolution - David Dorado Romo - Страница 22

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление17

SEVERAL EXCELLENT HISTORICAL works about the Mexican Revolution on the

border served as my guides during the writing of this book. Friedrich Katz’ The Life & Times

of Pancho Villa; Mario García’s Desert Immigrants; Oscar Martínez’ Fragments of the Mexican

Revolution;

Willivaldo Delgadillo and Maribel Limongi’s

La Mirada Desenterrada;

and

Miguel Angel Berumen and Pedro Siller’s 1911: La Batalla de Juárez, among others, provid-

ed very useful maps of the history and territory I’ve been exploring these past few years.

But the one historian who is perhaps the most responsible for getting me to write

about my own city is Leon Metz. I’ve run into him a few times at historical conferences.

The former law enforcement officer turned historian is an amiable man. He looks a little

like John Wayne and a little like Jeff Bridges. Everybody likes Leon Metz. He’s almost as

popular as the UTEP football coach. His books sell very well too. If you go to the histo-

ry section at any Barnes & Noble in El Paso, you

probably won’t find any of the books I’ve just

mentioned there. But you’re likely to find more

than a dozen books written by Leon Metz about

local gunfighters, sheriffs and Texas Rangers—

John Wesley Hardin, Pat Garrett, John Selman and

Dallas Stoudenmire. Occasionally Metz writes

about the Mexican Revolution too from that Wild,

Wild West cowboy perspective of his.

Let me give you an example. In Turning

Points in El Paso, Texas, the local historian is high-

ly critical of the revolutionary Spanish-language

newspapers that flourished in South El Paso

around the turn of the century. Metz—who does-

n’t read or speak Spanish—denounces many of

them as badly written “handbills” full of “emotion-

al, oftentimes hysterical overtones” whose content

“sounded impressive only to other social-anar-

chists.”2 He expresses displeasure with these publications that “frequently denounced the

United States (which protected their right to publish) as savagely as they did Díaz.”3 One

of those anarchistic newspapers he mentions is Regeneración, which Metz claims was

published out of the Caples Building in El Paso by Ricardo Flores Magón. (I’m not sure

how Magón—who established his headquarters in El Paso in 1906—could have published

his newspaper out of the Caples Building. The Caples wasn’t constructed until 1909.) The

Old West historian describes Magón as a friend of “bomb-throwers,” a man with “enough

real and imagined grievances to warrant psychotherapy for a dozen unhappy zealots.”4

Ay, ay, ay! Talk about bomb-throwers.

Them’s fightin’ words, as the Hollywood gunslingers of old used to say. They’re the

kind of outrageous distortions that would spur any self-respecting microhistorian worth

the name to reach for his laptop and write his own version of the past. Which I did.

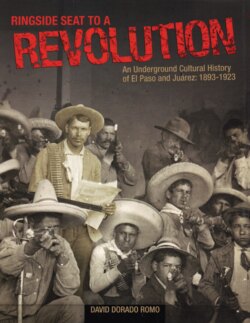

Silvestre Terrazas (second on left)

and the staff of his newspaper

La Patria in El Paso Street, 1921.

Between 1890 and 1925, more than

40 Spanish-language newspapers

were published in El Paso.

(El Paso Public Library.)

1

Luz Corral de Villa, Pancho Villa en la intimidad, p. 59.

2

Leon Metz, Turning Points in El Paso, Texas, p. 90.

3

Ibid.

4

Metz, Turning Points, p. 88.