Читать книгу My Green Manifesto - David Gessner - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеA BACKYARD WILDS

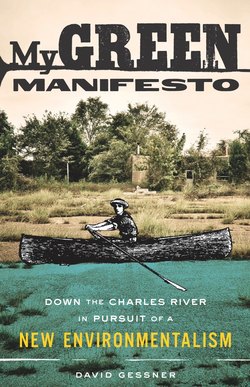

The original plan had been for Dan and me to paddle the entire river together, but it turned out that for Dan the business of fighting for the Charles takes precedence over the pleasure of floating on it. A state meeting interfered, so I am paddling the first day solo.

Earlier this morning, however, Dan took some time away from work to drop me off at the launch, driving way too fast down the back roads of Medfield and Norfolk while we drank tubs of Dunkin’ Donuts coffee. He explained that the kayak I’d be paddling was an expensive one and not really his but a loaner from a friend. As it turned out he was nervous enough about me navigating my first rapids that he drove to the Pleasant Street Bridge to coach me through the initial series of rocks. He was right to be nervous as I had mostly kayaked on ocean marshes before and, while the rapids on the Charles pale before true river rapids, they were challenging enough to do damage to the boat, if not to me.

Dan stared down from the bridge above, no doubt wincing when I slammed full on into a half-submerged boulder. After that I self-consciously picked my way along until, at last, I landed in a strong trough of current that whooshed me away and down the river.

That was how it started. Six hours have passed since then and I have not seen another canoe or kayak. What I have seen is a dazzling array of birds—hawks, wrens, warblers, orioles, tanagers, woodpeckers—and a variety of landscapes that not even the most optimistic nature lover would expect only miles from the tenth largest metropolitan area in the United States. After the exhilaration of the early rapids, I found myself riding a current of tannin-dark water that reflected back the overgrown banks of maple, swamp oak, and beech. Several miles later, the river began to double and triple back on itself, twisting and turning through the great marsh that divides Millis and Medfield, a landscape filled with the rustling of tall phragmite grass and the whistle-skreek punchlines of red-winged blackbirds.

The day’s weather has been as variable as the landscape with great cloud continents shifting overhead. At one moment I am paddling in scorching midsummer sun, shirt off and sweating, and the next I find myself in the midst of a rain shower. All the while water bugs play across the river, pock-marking the surface along with the raindrops. As I float past, painted turtles plop off the mud banks, swallows swerve above the river hunting for insects, fish jump, and at one point I watch a beaver plow by with a sprig of vegetation in its mouth, leaving a V wake behind.

I half-expected something like this, but not really like this. What I’m trying to say is that while I knew this trip would be kind of wild—if I hadn’t I wouldn’t have signed on in the first place—what I didn’t expect was the sheer thrill of the experience, the thrill of being alone and discovering a new place, a thrill that reminds me of my first time stumbling upon an Anasazi ruin while hiking through the desert in southeastern Utah. Not that it is as spectacular and novel as that, at least to my Eastern eyes, but the experience itself has held the same bubbling thrill. Part of this comes from the fact that I expected more houses and human intrusion. Occasionally I’ll notice a dock or rowboat that indicates I’m paddling through someone’s backyard, but more often the feeling is one of relative solitude with little indication that I am entering the home turf of over four million human beings. Furthermore, the evidence of human habitation, however minimal, is, in its own way, as thrilling as the long sections of trees. What you see of the houses has a secret childhood feel to it: that rope swing out over the river, the old dock with a dinghy tied up to it, those decayed stairs leading to the water. None of the lawns are of the enormous and mowed variety, and the few houses themselves are only glimpses through the branches and leaves. I can’t help but think how lucky the people are who live there, lucky to have a river moving like a dream through their backyards.

My point here is not to describe the lovely world, but rather to make some points about saving it. And yet, oddly, my first point is that the world is still lovely, even when it is limited and somewhat un-wild. In other words, for all of environmentalism’s cries of doom, there are still places like this river, teeming with life and flowing right through our backyards. Yes, the world is overheating, and, yes, we will get to that; but how about—before the flames of apocalypse consume the planet—we explore our own neighborhoods a little?

I think of my friend Bill Roorbach, whose house in Farmington, Maine I visited not long ago. The house itself was nothing special, at least not at first glance: a crowded two-story dwelling with warped floors that sat right on a paved road. But when he took me out into the backyard, I began to understand why you couldn’t shut him up about the place. Behind the house, there grew a great shambling garden and that was just for starters. From the garden we walked along a path through the briars and woods, “down to the stream,” he said, but when we reached the water, which I was expecting to look very docile—all quaint and New-Englandy—it was nothing like a stream. The small woods opened up and we were standing in front of a powerful surge of wide water, water that S-ed around and cut deeply into the opposite bank, water that looked more like a Western river than a New England brook. Instantly it became clear why he had brought me there, why he had showed me this before showing me his living room or study or anything else inside. He pointed to it with pride and without a word I got it. This is where I live, he was saying, This is why I live here. This is where I come to gather myself, be myself, and get beyond myself. This is where I come to get to know my neighbors, neighbors that include birds and beavers and muskrats and an occasional moose or fisher. And this is where I come to connect to the greater world since this un-stream-like stream eventually flows into the river and then that river flows into the ocean.

Well, his backyard is extraordinary, you might argue, as was Henry David Thoreau’s backyard, which held Walden Pond. But I think that is exactly the wrong point to take away. As a kid who grew up in Massachusetts, I can tell you that ponds like Walden are a dime a dozen, a few hundred others just like it scattered around the state. “Oh, it’s nothing special!” people often say when they first see the pond. Which is the whole beautiful point! It’s as ordinary as it gets, and that is why it’s so important. It means that your own ordinary backyard might just be extraordinary, too. It means that your own territory might also be worth exploring.

When most people think of the Charles, if they think of it at all, they imagine a tame and preppy river, a river that got into the Ivy League, a river of boathouses and scullers. But when Captain John Smith spied the Charles from Boston Harbor in 1614, he wasn’t thinking about scullers or tea parties or final clubs.2 Like any explorer worth his salt, his dreams were of discovery—the main chance—and in the river he thought he’d hit upon it. He took one look at its great gaping mouth and assumed that it was a raging torrent of water that cut deep into the continent. It turned out he was spectacularly wrong in this assumption: not only does the river not reach halfway to California, it barely makes it halfway to Worcester. What Smith had not anticipated was that the Charles, like many people, has a mouth too big for its body. His disappointment over the river’s length did not stop him from naming it after his king, forever saddling the poor river with a name that is stiff and a little goofy. Imagine the difference if he had called it “The Chuck.”

As for the river’s length, it covers, as the crow flies from source to mouth, about twenty-six miles, almost exactly the same distance as the Boston Marathon. This makes sense since the Charles, like the Marathon, begins in the town of Hopkinton. The difference is that the river, unlike the runners, isn’t interested in traveling straight and fast. By the time it wends its way to the harbor it has actually covered something closer to eighty miles, earning its Indian name of Quinobequin which means “meander.” That name is currently under debate, as is the river’s actual source—the good folks of Milford claim the river starts in their town, not in Hopkinton—but most agree that it emerges in the latter town, as my own observations confirm.

I had agreed to drive Dan’s boats from Cape Cod to his house in Boston, but, a born meanderer myself, before delivering the boats I had to go to Hopkinton to search for the river’s beginnings. With a large canoe and a kayak atop my car, I rattled down Granite Street, where I observed small muddy creeks trickling into a manmade reservoir named Echo Lake. I couldn’t see how to get into the lake since the woods were posted with signs that said NO TRESPASSING: TOWN OF MILFORD WATER SUPPLY, and I couldn’t very well leave Dan’s kayak and canoe unwatched, so I drove up a smaller street until I saw a woman in her front yard washing her car. I’ve always relied on the kindness of strangers, and sure enough when I pulled into the driveway and got out to say hi, the woman immediately pointed at the kayak and told a story about a recent canoe trip she’d been on. Her name was Amy Markovich and she ran a business called Echo Lake Adirondacks which sold the elegant wooden chairs that were displayed on her lawn. She was delighted that I was going to paddle the length of the Charles, and rushed inside to print out aerial photos of the lake, displaying them for me as though she were showing off pictures of her children. After she put the pictures away, she coached me on the best way to hike into the reservoir. She seemed genuinely proud to have this mysterious thing—the very source of the Charles—in her own backyard.

She let me leave the car in her driveway and promised to keep an eye on the boats. I followed her instructions and hiked back down the road before cutting in on the ATV trails as she’d suggested. After about a mile I came upon the lake, which gave me my first hint that there was a hidden wilderness within the confines of Boston’s suburbs. It’s true that my initial sight was of a pile of litter at the base of a red cedar—Coors empties, water bottles, and a Newman’s Own salad dressing bottle, as if these had been particularly health-conscious litterbugs—but what I saw next was the blue bowl of the lake itself. Silver shined through the birch and pine and, with its many small coves, you could easily imagine you were looking out at a lake in Maine or Canada. I tramped around for a while—following deer tracks in the mud, listening to a kingfisher overhead—and tried to determine the indeterminable: Which of those muddy brooks, barely trickles now in early summer, was the true source of the Charles?

After hiking out, I thanked Amy, promised to dedicate a chapter to her, then drove back down Granite Street and pulled over by a mossy graveyard to study the brooks to the north of the reservoir. These nameless incarnations are the first drops of what eventually will become the Charles—a truly modest beginning to a great river.3

On the other end of the reservoir, the water dribbled out of Echo Lake and along Route 85, next to Wendy’s and Pizza 85, gradually picking up force and momentum. But only gradually. If you judged this river just from its beginnings you would have to conclude that it would never amount to much; a shiftless townie river that wasn’t going anywhere much less the Ivy League. Unambitious, it seemed destined to do no more than dribble behind the strip malls of Milford. Of course I knew that the river, like a lot of us, would overcome its muddled beginnings.