Читать книгу My Green Manifesto - David Gessner - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеFIGHTING WORDS

I’ve always liked the word “turtle.” Like “boing” or “scrotum” it seems innately comic. Today turtles, specifically painted turtles, are my companions; over the course of the afternoon I see hundreds of them. Almost despite myself, I’m getting to know their yellow and dark-green striped heads, the orange under their shells, the glistening water on those shells before they plop into the water. It’s a beautiful sight, but let’s face it: This marsh is not exactly pristine and in the black banks of muck I see tennis balls and beer bottles and, mysteriously, dozens of orange golf balls. When I finally emerge from the marsh, I pass a dock with a large American flag, unfurled for the coming holiday, and, next to the dock, a massive fire pit on the riverbank.

It isn’t until mid-afternoon that I pass the first human being I’ve seen since leaving Dan this morning. This is an amazing fact considering I’ve been paddling through the suburban towns of Medfield, Millis, and Sherborn. It’s a guy about my age fishing under a bridge. He claims to have caught eighteen fish—most recently a catfish and a bass. The Charles, I know, used to be a dead place. “Dirty Water,” as the song went, so even the possibility that he has caught this many is reassuring. The guy asks me to look for a lure he lost downstream and I do after shouting goodbye.

Late in the afternoon I see another kayaker. Strangely though, rather than a feeling of companionship, I experience a prickly irritation, something maybe not too dissimilar to the way the great blue heron feels upon seeing me. What is this guy doing on my river? Of course I shout hello but it might be more honest to emit a heron-like sproak! The moment passes soon enough, though, and I am alone again. I paddle below a railroad trestle, navigate a field of sunken logs, and enter the Rocky Narrows Reservation, where I will camp for the night. Rocky Narrows is conservation land, owned and protected by the Trustees of Reservations.

I set up camp on a little ledge of grass a few feet above the river. Here the water pivots around my campsite and the little beach where I pull up the kayak. Nearby, a large willow kneels, dipping its hair in the river. Once I feel organized, I grab my pack and pull out a beer and a sandwich and sit with my legs hanging over the ledge to drink my beer and listen to the kissy noise of a chipmunk. A Baltimore oriole flashes by.

After I finish the beer, I reach deep into my dry bag, uneasy about the shameful task I have to perform next. Dan and I have agreed that I will call him to fine tune the morning’s meeting, which means this is officially my first camping trip armed with a cell phone. But when I pull the phone out I discover that it is dead. Not just a little dead either—there is nothing that says “No Service” or “Dead Battery” or even “Alltell.” No, this is utter death. I shake it a little and push a few of the buttons in simian fashion and then think about slamming it on a rock or something. What follows is a strange moment of panic: egads, I’m disconnected. I can feel my mind beginning to obsess over the problem, and can imagine spending the next couple of hours trying to resuscitate the machine. Not wanting to go down that ugly route, I jam the phone back into the dry bag and open a second beer. To my surprise, it doesn’t take but a minute to move beyond the phone crisis. So strange that even just turning off a cell phone, or being unintentionally disconnected from one, is a step into a wilder world.

I sip the beer and watch a long finger of light shaft down through the pines. It occurs to me that this would be a good spot to have sex if I were traveling with, say, my wife. I scribble down notes for an essay about wild sex in the wild—anything to help jazz up Nature’s dowdy reputation. Meanwhile, streaks of sunset bleed into the river as a beaver plows by, heading back upstream. A barred owl lets out a series of classic whoos. Solo camping can be both thrilling and terrifying. I remember the first time I spent a couple nights alone in California’s Lassen Park; I was sure the deer grazing outside the tent were killer bears. Over the years, I’ve become gradually less nervous. The woods behind me feel substantial and it seems I have the place to myself, at least until I hear a loud stomping and yelling coming down one of the paths. What enemy tribe is this? Three joggers and two dogs crash their way toward my campsite and suddenly my patch of wildness feels a little tamer. When they see my tent they grow quiet, and while they stop to let their dogs splash in the river I tell them about my trip. To my own surprise my voice sounds excited, almost overly so, and I realize I am already turning the day into a story.

I have always enjoyed spending days alone—solo days carry a special thrill—but for me, as a writer and storyteller and human animal, there is something else going on during these trips. I am readying my narrative, preparing to tell someone, itching to recreate my day. Pity the poor innocent who is the first person I bump into after these trips—the unlucky woman, for instance, who sat next to me at the coffee shop counter in Chester after my trip into Lassen—who gets her ear talked off.

I ask the runners how they happen to have come this far into the woods, and learn that I’m not quite as secluded as I hoped: there’s a trailhead and a road a couple of miles away. After they leave it quickly grows dark. I urinate around the camp’s perimeters to ward off other visitors and return to my ledge over the water, waiting for the moon, breathing in the slightly skunky smell of the river. I consider smoking the cigar I’ve stuffed in my dry pack, but when the moon doesn’t show up, I climb into my tent. The night is quiet enough, despite the steady highway howl in the background. I settle in my sleeping bag with a book and flashlight.

I’m reading a book called Break Through, written by Ted Nordhaus and Michael Shellenberger, two lifelong environmental advocates best known for releasing an attention-grabbing essay called “The Death of Environmentalism.” That paper, which sparked a lively debate, advocated breaking environmentalism out of its granola ghetto and tackling global warming head-on, which, according to the authors, and contrary to most conservatives, would actually create jobs and help the economy. I thought I’d pick up the book because it seemed to fit my present mood, and I’d heard that Nordhaus and Shellenberger, like me, have grown tired of both musty mysticism and hysterical apocalypse-ism, favoring a more practical, hard-headed brand of environmentalism. I find myself nodding through their initial arguments as the authors criticize yet another manner of speaking about nature, that of the technocrat.

It gradually dawns on me, though, that the two authors seem to rail against the technocracy with their own form of techno-speak. I really wanted to like this book, but while I am full of admiration for these two men—mostly for their willingness to jab a stick in the environmental hornets’ nest—as I read on it seems to me that they ultimately lack a truly creative response to crisis. They want “greatness,” which they conveniently define as their own Apollo energy proposals. They tell me that what drives those of us interested in nature—which they consistently, ridiculously define as “hiking”—is a kind of post-materialist affluence, mocking anyone who might have more complex reasons to seek out the non-human world. Meanwhile, they happily belittle the contributions of old time environmental heroes like Rachel Carson. They seem to believe that human beings started to think about nature in the nineteenth century, around the same time Thoreau did, conveniently forgetting, or misplacing, the million years or so when we lived in the natural world.

In fact, what astounds me as I make my way through their text is that I don’t encounter a single rock or tree or bird. Before too long I’m tempted to unzip the tent and toss the book in the river with the rest of the debris headed seaward. It’s not that I disagree with a lot of their premises. Their willingness to criticize their august environmental forefathers, to suggest that the problems of poverty and environmentalism are deeply intertwined, is definitely praiseworthy. And whether or not you agree with them, their take is refreshing in that they try to shake things up. They also, for the most part, attempt to translate environmental policy into English while eschewing the gloomy rhetorical style that environmentalists have been known for since the dark days of the seventies when Jimmy Carter and his sweater first preached to us about conserving.

And yet the book is a hard slog. The authors constantly stress the need for a larger “vision,” using the word again and again, but their own vision remains a little murky. Like so many professional activists, they seem to suffer from conservative think-tank envy, waxing poetic about the Republicans’ ability to appeal to our self-interest through “core values,” as if values were merely strategic and vision merely a selling point. They suggest, for instance, that environmentalists focus more on “the job creation benefits of things like retrofitting every home and building in America.” Well, retrofitting is nice, but it’s not exactly a vision for a livable future—maybe just a trip to Home Depot.

Then there’s a larger problem: The authors tell us that environmentalists don’t acknowledge the potential of human beings, and that they, on the other hand, hope to free our great human potential. But their view of human beings is cobbled together from a mish-mash of humanist psychologists, neo-conservative critics, and what they keeps stressing are the great breakthroughs of social psychology over “the last fifty years,” which seems a particularly arbitrary time period when considering human development.

What does it all add up to? They sell human beings way short. They discount, for all their talk of vision, the power of ideas. Take environmentalism, for instance: according to the authors it came about in the sixties because we as a society had become “post-material” and affluent, which led to the great liberal agenda that environmentalism was part of. They dismiss as antiquated and dusty anyone who buys into the old mythos, anyone who dares believe that actual thinkers and writers, like Rachel Carson, had an influence on how people acted. Carson’s story in fact is just the sort of cobwebbed tale they think we must get rid of. They don’t exactly explain why this is so, nor do they rebut the impact of her ideas on her times—how, for instance, Carson’s book led directly to the congressional hearings that led to the banning of DDT and the founding of the Environmental Protection Agency. No big deal, I guess. We are nonetheless supposed to buy their premise, based on a crazy quilt of sources, that environmentalism’s flowering owed nothing to ideas but was a mere sociological byproduct of wealth.

The most thought-provoking chapter in their book considers Brazil, but it follows an argument that is deeply confusing, and a bit disturbing. It goes a little like this: Americans are really only concerned about the environment because we are affluent and “post-materialist” (not because human beings evolved in, and therefore probably have some affinity for, nature) and other countries will only care about the environment once they become post-material. Therefore it is imperative that we, rather than in any way try to restrain growth, encourage other nations, like Brazil, to follow us down the post-materialist path. So how can we help save the rainforest? Since only post-materialists can care about the environment, we need to create economic stimulus packages so that other countries become affluent, and post-material, and therefore are ready to save their environment that—oops—will already have disappeared in the process of their becoming post-material. They claim we are hypocrites not to try and help others to have what the United States has, but then again they acknowledge that if others have what we have the world will be ruined.

Nordhaus and Shellenberger begin their book by citing Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I have a dream” speech, and end by again claiming that what we need is vision. But Martin Luther King, Jr.’s vision was a clear and passionate one: All people should be treated equally and fairly. Here is their dream, as I summarize it: Countries should achieve an abundance similar to the United States and gradually achieve a post-materialism that will allow them, gradually, to get interested in environmentalism (and hiking). Not quite as catchy as King’s, you must admit. It makes you wonder why they so dislike the old dream—the one about “saving the world.”

What most surprises me is how these two ever ended up going into a field that had the word “environment” in it. Their bios state that they have spent their entire careers as part of, or advisers to, environmental organizations, and you can’t help but feel they would have benefited from taking a few other jobs, maybe even one that got them out of the office. It isn’t just that they seem to have little respect for the idealistic, passionate environmentalists who came before them, it’s that I see no evidence at all that either of these men, at any point in their lives, have ever interacted with the nature that they so like to theorize about. They seem to care little for the natural world, except as it pertains to theories and models.

You’ll have to forgive me, dear reader, for going on so long about these two individually, but as I fume I realize they are coming to embody for me much of what is wrong with the environmental movement these days: primarily the belief that humans are only data points; that theory and policy will guide us beyond the troubled present we occupy and the future it suggests. Policy and theory are great, but they’re only as strong as the belief of the people meant to follow them. So Nordhaus and Shellenberger come in for a beating here, but only because, to date, they’re the best effigies I’ve found yet for the environmental technocracy. Sorry guys.

I sleep pretty well on a cushion of pine duff and only get up twice during the night. Once to piss and another time when a loud noise jerks me out of sleep—just the commuter train rumbling past a couple of miles away, letting off the shriek of its whistle. And then another noise, much stranger, a noise that the train’s whistle calls up. The train initiates the dialogue, but the coyotes continue it eagerly. They howl wildly for a good half hour after the train has passed, their howling in turn setting off the distant yipping and wailing of domestic dogs. The blurry dialogue between what is wild and what is tame seems particularly appropriate as a lullaby. I think back to when I lived in the city this river is bound for, the year my daughter was born and the year I tracked the coyotes that have made this their urban territory, their tracks then tracing a path in the snow along the frozen Charles, right down into the city’s heart.

I listen to the chorus for a while, how long I don’t remember, before drifting back off to sleep.

I wake to a river covered with mist. A blanket of white punctuated by fingers of sunlight stretching down toward the water as small whirlwinds of steam rise up to meet them.

Groggily, I return to last night’s argument with Nordhaus and Shellenberger. It turns out that they bug me as much in daylight as after dark. These two claim to dislike scoldings, but their book sure feels like one. After reading for awhile, I prowl my small patch of shoreline. I feel chastised and it isn’t chastisement that we need. We need the opposite. We need language—simple, plain, impassioned—that can be used both to describe our love for nature and to rally humans, actual people living in the world, to the fight to save it. A language that calls us away from computers, think tanks, and ethereal theories so that we may return to the ground truths of the places we call home. Why talk about language again, you ask, when there are polar bears to save? Because language comes first, the source, the rallying cry before the fight.

One thing I do enjoy in Nordhaus and Shellenberger’s book is their fondness for Winston Churchill. The biographer William Manchester wrote of Churchill’s speeches during World War II: “Another politician might have told them: ‘Our policy is to continue the struggle; all our focus and resources will be mobilized.’ ”4 Instead Churchill’s words rose to the occasion and he spoke directly of sacrifice, of “blood, toil, tears, and sweat.”5 If we are indeed entering a time of crisis—and everyone tells us we are—then we will need the direct and urgent language of crisis, a language that fills us with hope, despite the darkness.

Part of what a living language must do is address the crisis itself, but more importantly it must tackle the psychology of environmentalism. How do we go from engaging in a full-on panic attack to taking small steps, from listless apathy to the beginnings of action on a wide and wild scale? For me those questions spring from this one: Why save a world you don’t care about? After all, how do we fight for something that is no longer a part of our lives? Or to put it another way, how do we start to care for something we have nothing to do with? Beyond buying into the faddish popularity of our new all-green, all-natural, consumerism, the majority of people in this country have little to no contact with the natural world in their daily lives. What this new language must do, in clearly unsentimental terms, is to cultivate a return to, a love and delight for, wildness. Because that is what we are losing when we lose daily contact with birds, animals, trees, water, and land. Part of the problem, of course, is what I would call the nature calendar view of nature: over there is spectacular untrammeled NATURE and then there’s what we’ve got. But I am here to say that what we’ve got, right here, trammeled and all, ain’t so bad. We simply need to fall in love with what is left, with the limited wildness that remains. That is what Dan Driscoll did with the river I’m staring out at now. He saw past the piles of Coors Light cans and shopping carts floating in the water and fell for the coyotes, the hills, and the black crowned night herons that had come back to nest along the shore.

My own experience suggests that love, and sometimes hate, are much better motivators than theory. For several years—the most intense years of my life in many ways—I lived on a deserted beach on Cape Cod, squatting in the homes of the wealthy during the off-season, and during that time I fell hard for one particular section of rocky beach.

I didn’t clearly recognize it at the time but that period was a love affair. And then the love affair was interrupted when, one day, someone began constructing a trophy home on the bluff. I was filled with something close to rage, and for the first time in my life, found myself attending town meetings and writing letters of protest. I bring this last point up, not to boast of any strain of righteousness, but because I believe it speaks to what motivates many of us to act. The writer Jack Turner puts it well: “To reverse this situation we must become so intimate with wild animals, with plants and places, that we answer to their destruction from the gut. Like when we discover the landlady strangling our cat.”6 Our greatest environmentalists, Teddy Roosevelt and John Muir among them, were instinctive fighters, who also happened to spend plenty of time outdoors. More of us need to follow their lead. It is not my place to offer pep talks, aphorisms, or dictums. But if I had to give one piece of practical advice it would be this: Find something that you love that they’re fucking with and then fight for it. If everyone did that—imagine the difference.

If environmental psychology is my topic, some of the pressing questions are: What allows a person to go beyond paying lip service to nature and to actually live with it in this modern, muddled world? How can we fall in love with something so limited and wounded? And how can we go from loving to fighting? Finally, we must consider what role, if any, that hope plays in these questions.

A while back I read an essay by a writer named Derrick Jensen, in which he argued for a politics of hopelessness. I couldn’t disagree more. Without hope and the energy it provides we curl into the mental equivalent of the fetal position, hiding from the world. “Where there is no hope, there can be no endeavor,” wrote Samuel Johnson.7 He was not talking about the Disney variant of hope, but the real animal. It’s the light that filters down into our dark brains, sparking our neurons. The brightening after darkness, which energizes like the quickening of the world in spring. A thawing and movement into activity, an activity that then gains momentum. This is hope as a physical thing: The hope that spring inspires, after the long winter.

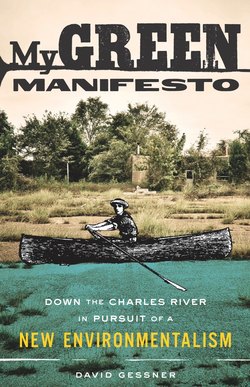

It is just this sort of hope that energizes me now as I pace this bank, hope spiced, of course, with a dash or two of vitriol. A fine cocktail. It occurs to me to write a manifesto, but one quite different from Nordhaus and Shellenberger’s. My agenda is simple: To describe the ways that my own life, and the lives of some people I admire, are connected to the natural world, and the benefits that come from that connection, benefits that are not always obvious. To provide a way for those of us who would blanch at calling ourselves environmentalists to begin to at least think of ourselves as fighters, in the way that citizens suddenly think of themselves as soldiers during times of war. Finally, by both argument and example, to provide a new language for those of us who care about nature.