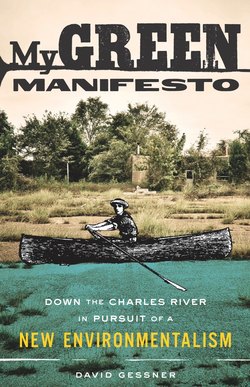

Читать книгу My Green Manifesto - David Gessner - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTHE FIRE THIS TIME

I paddle through the afternoon, watching the pulsating light on the under branches of trees. Somewhere on the other side of this living green wall cars are rushing to and from the city, but that doesn’t concern me. How many types of weather can I name from the day? Too many to count. The wind comes up, the water ripples, the clouds blow over and create a chill, then disappear; after the sun bears down, the wind stops, and a short rain falls. Every turn of the river is different. There is no formula for it. As I slide past the forested banks whole riverside landscapes reflect in the water. The cloud continents rush overhead and the rain soaks me again. Shaggy weeping willows bow to the river.

What would a new environmental music sound like? It might, at the risk of coming off like the mystics I just ridiculed, sound a bit like this river. Burbling, lapping, rushing, calm, excited, but above all fluid. And contradictory, too, rushing one way but filled with back eddies and counter-currents. Uncertain and confident all at once.

Before I go all Siddhartha on you, however, let me add that it should also be blunt. Wedging downward past nineteenth-century romanticism and tunneling back toward the practical source of “nature language”: daily dialogues with fellow tribesmen, directions to the kill, songs sung by generations upon generations of roaming hunter-gatherers. Ugh. Wolf scat. Look—berries. That’s a kind of music, too.

Of course it’s hard to keep a fluid, riverlike mind in this time of adamancy and increased hysteria. We live in an age of blowhards, windbags, and he-who-shouts-loudest wins. In the environmental community this means increasingly shrill warnings about our pending doom. We are never allowed, not for a moment, to forget GLOBAL WARMING and its corollary admonishment that we must SAVE THE WORLD. While I know it is sacrilege to say it, I still don’t believe that “global warming” is the answer to every question left on earth. Frankly, the subject exhausts me. I find my optimism and energy waning when my brain turns to that ever-popular environmental topic: The End of the World. Perhaps that is because I, like most of us, am not built to think in terms of the apocalypse. Too much of it and I am left stunned, helpless, curled up in a fetal position on the kitchen floor.

It’s not that I disagree with the experts. If they are right, and they probably are, the next century will be a dismal one. Our present six billion will become ten. Our resources will dry up as the world warms and our population essentially doubles. Massive extinctions are likely to occur—in fact, they are already occurring—animals that have inhabited the planet for millions of years will be gone forever. The truth is that it’s great to care about sentences and write books and all, but I’m not sure anything is going to help. If the predictions are even half-correct, we’re fucked.

I admire all the thinkers who try to wrestle with these concepts and come up with ideas that will help. I admire all those brave enough to try and offer words and solutions. But for my part, I can’t help but despair. I’m out of my league really, and in that I’m not so unlike most of us. When it comes to politics, I have no global plan or solution. I’m sorry. It is not what I’m good at and maybe it’s not what the animals that we evolved into are good at. One of the religious purposes for the concept of an apocalypse was to force us to admit that life was terrifying beyond the ken of mere human beings. And it is beyond the ken.

If you are like me, there is something particularly unpleasant about the fashion of apocalypse currently in vogue. At least with nuclear annihilation everything would end quickly. And at least it wouldn’t so obviously be each of our own faults. Our current fantasy of disaster has a distinctly unpleasant aspect in that we should all feel personally responsible. For the end of the world. Drive your car too long or take a hot shower and you’re contributing to the great, final doom.

It isn’t just about feeling guilty either. I question the effectiveness of using the nagging tone in which so many of these announcements of doom are broadcast. You may find yourself wishing that, even if the doomsday predictions are entirely accurate (down to the last minute and extinction), even if our fate is sealed (or, almost sealed as they always like to say, giving us a last second chance at reform), even if it is all true (and I, for one, will admit it is true, more or less), even if all this is the case could we just SHUT THE FUCK UP ABOUT IT FOR A MINUTE? Could we at least take a week off from new projections of doom? A month off from talk of the apocalypse? Maybe even a year-long moratorium on books that begin with the words The End of, The Death of, or The Last?

I will be accused of wanting to bury my head in the sand. But I don’t want to bury my head; I just want a short fucking break to remember that there are good parts about being alive. I am not Henry David Thoreau, I get that, and I live in a limited, depraved, depressing time; but I am here to say that I can still experience joy and yes, maybe even a little transcendence, even when watching a river that is flowing behind a Stop & Shop. I don’t want to act naïvely, but I do want an environmentalism that I can live with; one that is a part of my everyday life, not running roughshod over it. Imagine living with a spouse who feels the need to scream, several times a day, “THIS MARRIAGE IS OVER! WE’RE DOOMED!” It’s not so different than being part of a group that is always erupting with, “THE WORLD IS ENDING!” Yes, okay, sure, we know it’s doomed, but could we just be quiet for a while, watch some TV maybe, go for a walk? Nothing is going to get better overnight, so maybe it’s time to think about a more effective way of shouting?

What I am arguing against, I suppose, is an environmentalism that feels like the intellectual equivalent of a panic attack. Doesn’t it make sense to work toward a more integrated environmentalism, incorporating our selves, our worlds; a saner, calmer, more commonsensical environmentalism; an environmentalism that accounts for quirks, hypocrisy, nuance, comedy, tragedy? Of course even as I write these words I hear the counter argument, the argument of that imagined shrill spouse: “WHAT THE HELL ARE YOU TALKING ABOUT? HOW CAN YOU HAVE SOME SORT OF LAID-BACK APPROACH TO THE END OF THE WORLD?”

It’s not too hard to see why most of us don’t spend a lot of time dwelling on these larger issues. Who wants to feel that knot in their chest, that twisting in their gut? The feeling of panic I get about the state of the world is not so different, on a personal, physical level, from the tightness I experience when worked up about the state of my own finances.

Paddling, it turns out, is a fairly effective way to shut up one’s mind. Dan did a lot of it in those first days working for the state, getting to know the river he would soon be fighting for. Today, paddling helps me turn from brain to body. Whatever else kayaking is, it is a form of work, and work, starting with the taking of small actions, is the only reliable way I know to escape from those insomniac anxieties that can strike even in broad daylight. In this case, that means rotating my paddle in and out of the water. Feeling the sun on my face, the sweat trickling down my neck as I paddle harder. Not that this is truly a “way out” of the problem, not that my paddling will help with global warming in any way or form. But it is a break, a respite, before returning fresh.

And before long I am feeling good. My thoughts calmer, my muscles stronger. Birds also help pull me outward. I watch the flashing blue backs of swallows as they skim over the water, scooping up insects in mid-flight as I paddle through a channel some forty feet wide, between banks high with grasses, viburnum, and the occasional willow tree. Through my binoculars I can study the flight of one particular swallow, intrigued by its mussel-orange belly, trying to trace its every turn and twist, and then, concentrating even more deeply, trying to anticipate where it will turn or bank next. I can actually watch the moment it opens its bill and snaps—the exact moment it catches a damselfly out of the air. I follow the bird with my gaze as it hooks back over the bank, digesting.

From the trees near the banks I hear a song—“peterpeter-peter” —a tufted titmouse. The titmouse sings for two main reasons, to define his territory and to woo a mate. It’s late in the season for the latter, so maybe he, like the heron, is letting me know I’m an intruder. This bird’s song is partly inside it, encoded, handed down from its parents and their parents. Some species—herons and hawks and ducks, for instance—will never expand their repertoire beyond this genetic heritage, or if they do expand, it will be by the nudge of accident. But for my titmouse, and for most songbirds, their music is only partly in the genes. It is also learned, which means it is varied and individual. This is why a modern mockingbird can imitate a chainsaw or car alarm. A bird’s song, then, belongs both to their species and themselves. Donald Kroodsma, the dean of avian vocal behavior, writes: “Listen carefully to robins or individuals of almost any songbird species as well, and you can hear how each bird sings with his own voice by varying his songs in either small or large ways from birds of his own kind.”

My friends from my younger days laughed when they found out I had gotten deeply into birds. Birds, of all things. Fancy, pretty little birds. These friends were mostly athletes and they saw me as an athlete, too, not to mention as someone who was gruff and crude and drank too much. And now . . . birds!

What I might have said to them, if I’d had the nerve, was that it was nothing fancy or pretentious that had led me to birds. Quite the opposite in fact. I believe that birds held the secret to something I’d been searching for. I slowly came to understand that it had been contact I’d been after the whole time, and that I had first sought out contact in drink and sport. What I might have said was that the contact that I craved was right there in an osprey’s dive. But maybe it’s best that I kept quiet. They would have laughed back then, I’m sure. But they are getting older now and it will not surprise me if a few of them gradually find themselves turning to birds.

But still, the question: Why birds? I mentioned contact but it goes beyond even that. I think the answer ultimately has something to do with both narcissism and its opposite. I go to birds selfishly but I also go to them because they are one of the few things that are capable of prying me out of myself. They don’t do this always or even often and when they do it it’s not for very long. But they do it. They give me transport along with contact. For that, and the fact that they fly, I love them. I don’t like the geeky aspect of learning their names and calls as much as I like the sheer simplicity and transcendence of their lives. I am not talking about god here, and maybe god is not necessary. Maybe bird is enough.

At my worst moments I live trapped in what my old professor Walter Jackson Bate called “the subjective prison cell of self.” I try to remember, during the dark, depressed, inward-turned times, that not only is there a world beyond me but that I have gone there—however briefly—and believe I will be able to go there again. This is the most reassuring thing I know. Not success or god or the big rock candy mountain. But the simple fact that there is still a world beyond us. That we are not alone.

Let’s just assume for a minute that the experts are right and the world is doomed. Let’s assume that when my four-year-old daughter is my age she will be living in a crowded slum apartment eating human-being patties like those in Soylent Green. What am I supposed to do about that? As I said above: I just don’t fucking know.

And how much does my long-term doom affect what I will do on a day-to-day basis?

I will still drink my coffee; still make my things-to-do list; still go to work; still pick up my daughter at preschool; still watch my birds. I might think about eco-doom once or twice a week but it won’t truly impact my consciousness. When will that change?

Perhaps there will come a time when the problem is so pressing that we all rally around to fight. Perhaps we will pull an all-nighter and summon Bruce Willis and his crew of roughnecks and somehow save the world. But while this last is a story I would like to believe, a story I hope for, it isn’t a story that I am going to put money on. Gloom and doom, while less palpable, seem a more likely forecast.

And this is just about where my brain usually freezes up again. This is where I always feel the need to take things down a few notches, to leave the problem behind for a while and turn to other concerns. Extreme fear—THE END OF THE WORLD!—leads to extreme thinking. Trembling before the world, we create apocalyptic scenarios and cast ourselves as prophets. Consider your own life: the way during a middle-of-the-night panic your thoughts spiral away from Earth, zigging and shooting and swirling upward. How to ground those thoughts? Where to root them?

I don’t know about you, but my own inclination is to return to the personal, which is not to turn from the altruistic to the selfish. What I am suggesting is that, as pressing as the end of the world is, most of us have other fish to fry. I am not saying that this should be the case, just that it is. And I am not the first to suggest that, as vital as saving the world is, saving ourselves is of some importance, too.

The dark secret of kayaking is that it can be pretty boring. Even with the stimulation of the changing weather and animal life, there are moments when the activity grows tedious and my back and arms ache. Doing anything for eight hours will wear you down. On the other hand the boring moments are more than counterbalanced by the delightful ones. On the banks of the marsh I see empty mussel shells and wonder if I’ll catch a glimpse of a river otter. That would be worth any tedium. Less romantic than imagining that sight, but equally stimulating, is the twenty minutes I spend paddling through what signs announce as a LICENSED SHOOTING PRESERVE. Gunfire tends to keep the human mind alert.

The noise dies out as the river seems to change to creek. Suddenly I am twisting and turning back on myself in a sinuous maze, the marsh undermining any sense of progress. It often feels like I am going backwards, but I know that if I just keep paddling I’ll cover the thirteen miles I need to before I get to my campsite by nightfall.

As I slog through the marshy passage, red-winged blackbirds, proud of their blazing orange epaulets, cluck at me, scolding. They let go with their three-word song, the last note like a punchline. Calmer now, I return to the ideas that spooked me an hour ago. It would be mauling a metaphor to say that water grounds me, but at the very least all this sweating and sun and full-on weather helps me consider the prospect of our environmental annihilation without risking another panic attack. I know I can offer no global theories, but maybe I can do something more modest: offer examples of people, like Dan, who have made nature—and fighting for nature—part of their lives and seem the better for it. This may not be much help in the face of the greater gloom and doom, but it’s really all I’ve got.

I suspect that this is something like the way Dan felt when his superiors first sent him off to work on the river, almost as a prank. He must have been overwhelmed by the seemingly impossible problem of greening the Charles. Why impossible? Because the land he needed, if he were to re-plant the river’s banks, had been owned or appropriated by individuals and corporations, and had been for decades. How could he possibly convince them that they should relinquish something they thought theirs? Did he glimpse right away that this would be his life’s work, did he follow the vision from the start? No, it would have seemed preposterous. And if he had allowed himself to get excited, it would have led to excitement’s opposite: panic and despair.

I wonder when it started to change for him. When did the fear and anxiety turn into something else? When did that frozen feeling in his brain begin to melt into momentum? Because, that is the thing about impossible tasks. Yes, they are intimidating; yes, they are daunting; yes, they can paralyze us. But they also can excite us, challenge us, enlarge us. What if I can really do this? he must have thought at some point. Anyone who has tackled anything big—building a house, fighting a battle, writing a book—knows the joy of the moment when the tide finally turns. And if the task is Quixotic, all the better. In his book, Life Work, the poet Donald Hall records the moment when he asked the sculptor Henry Moore what “the meaning of life” was. Moore replied: “The secret of life is to have a task, something you devote your entire life to, something you bring everything to, every minute of the day for your whole life. And the most important thing—it must be something you cannot possibly do!” Exactly! Perhaps there was even a point where Dan started to relish how absurd, how huge, the task at hand was.

Tell me to save the world and I will panic. Some jobs are simply too big, too daunting. Too much for one individual. But tell me to save a chunk of that world, a river say, and I might just become engaged. Give me something to work at, to work with, outside myself, and I will.