Читать книгу Polgara the Sorceress - David Eddings - Страница 10

Chapter 3

ОглавлениеThen I proceeded to give my father a piece of my mind – several pieces, actually. I told him – at length – precisely what I thought of him, since I didn’t want him to mistakenly believe that Beldaran’s sugary display of sweetness and light was going to be universal. I also wanted to assert my independence, and I’m fairly sure I got that point across to him. It wasn’t really very attractive, but I was only thirteen at the time, so I still had a few rough edges.

All right, let’s get something out in the open right here and now. I’m no saint, and I never pretended to be. I’ve been occasionally referred to as ‘Holy Polgara’, and that’s an absolute absurdity. In all probability the only people who’ll really understand my feelings as a child are those who are twins themselves. Beldaran was the absolute center of my life, and she had been since before we were born. Beldaran was mine, and my jealousy and resentment knew no bounds when father ‘usurped’ her affection. Beldaran and her every thought belonged to me, and he stole her! My snide comment about the ‘scene of the crime’ started something that went on for eons. I’d spend hours polishing those snippy little comments, and I treasured each and every one of them.

Many of you may have noticed that the relationship between me and my father is somewhat adversarial. I snipe at him, and he winces. That started when I was thirteen years old, and it didn’t take long for it to turn into a habit that’s so deeply engrained in me that I do it automatically now.

One other thing as well. Those who knew Beldaran and me when we were children have always assumed that I was the dominant twin, the one who took the lead in all twinly matters. In actuality, however, Beldaran was dominant. I lived almost entirely for her approval, and in some ways I still do. There was a serene quality about Beldaran that I could never match. Perhaps it was because mother had instilled Beldaran’s purpose in her mind before we were ever born. Beldaran knew where she was going, but I hadn’t the foggiest notion of my destination. She had a certainty about her I could never match.

Father endured my ill-tempered diatribe with a calm grace that irritated me all the more. I finally even lapsed into some of the more colorful aspects of uncle Beldin’s vocabulary to stress my discontent – not so much because I enjoyed profanity, but more to see if I could get some kind of reaction out of father. I was just a little miffed by his calm indifference to my sharpest digs.

Then in the most off-hand way imaginable, father casually announced that my sister and I would be moving into his tower to live with him.

My language deteriorated noticeably at that point.

After father had left uncle Beldin’s tower, Beldaran and I spoke at some length in ‘twin’.

‘If that idiot thinks for one minute that we’re going to move in with him, he’s in for a very nasty surprise,’ I declared.

‘He is our father, Polgara,’ Beldaran pointed out.

‘That’s not my fault.’

‘We must obey him.’

‘Have you lost your mind?’

‘No, as a matter of fact, I haven’t.’ She looked around uncle Beldin’s tower. ‘I suppose we’d better start packing.’

‘I’m not going anyplace,’ I told her.

‘That’s up to you, of course.’

I was more than a little startled. ‘You’d go off and leave me alone?’ I asked incredulously.

‘You’ve been leaving me alone ever since you found the Tree, Pol,’ she reminded me. ‘Are you going to pack or not?’

It was one of the few times that Beldaran openly asserted her authority over me. She normally got what she wanted in more subtle ways.

She went to a cluttered area of uncle Beldin’s tower and began rummaging around through the empty wooden boxes uncle had stacked there.

‘I gather from the tone of things that you girls are having a little disagreement,’ uncle said to me mildly.

‘It’s more like a permanent rupture,’ I retorted. ‘Beldaran’s going to obey father, and I’m not’

‘I wouldn’t make any wagers, Pol.’ Uncle Beldin had raised us, after all, and he understood our little power structure.

‘This is right and proper, Pol,’ Beldaran said back over her shoulder. ‘Respect, if not love, compels our obedience.’

‘Respect? I haven’t got any respect for that beer-soaked mendicant!’

‘You should have, Pol. Suit yourself, though. I’m going to obey him. You can do as you like. You will visit me from time to time, won’t you?’

How could I possibly answer that? Now perhaps you can see the source of Beldaran’s power over me. She almost never lost her temper, and she always spoke in a sweetly reasonable tone of voice, but that was very deceptive. An ultimatum is an ultimatum, no matter how it’s delivered.

I stared at her helplessly.

‘Don’t you think you should start packing, dear sister?’ she asked sweetly.

I stormed out of uncle Beldin’s tower and went immediately to my Tree to sulk. A few short answers persuaded even my birds to leave me alone.

I spent that entire night in the Tree, hoping the unnatural separation would bring Beldaran to her senses. My sister, however, concealed a will of iron under that sweet, sunny exterior. She moved into father’s tower with him, and after a day or so of almost unbearable loneliness, I sulkily joined them.

This is not to say that I spent very much time in father’s cluttered tower. I slept there and occasionally ate with my father and sister, but it was summer. My Tree was all the home I really needed, and my birds provided me with company.

As I look back, I see a peculiar dichotomy of motives behind that summer sabbatical in the branches of the Tree. Firstly, of course, I was trying to punish Beldaran for her betrayal of me. Actually, though, I stayed in the Tree because I liked it there. I loved the birds, and mother was with me almost continually as I scampered around among the branches, frequently assuming forms other than my own. I found that squirrels are very agile. Of course I could always become a bird and simply fly up to the top-most branches, but there’s a certain satisfaction in actually climbing.

It was about midsummer when I discovered the dangers involved in taking the form of a rodent. Rodents of all sorts, from mice on up the scale, are looked upon as a food source by just about every other species in the world with the possible exception of goldfish. One bright summer morning I was leaping from limb to limb among the very top-most branches of the Tree when a passing hawk decided to have me for breakfast.

‘Don’t do that,’ I told him in a disgusted tone as he came swooping in on me.

He flared off, his eyes startled. ‘Polgara?’ he said in amazement. ‘Is that really you?’

‘Of course it is, you clot.’

‘I’m very sorry,’ he apologized. ‘I didn’t recognize you.’

‘You should pay closer attention. All manner of creatures get caught in baited snares when they think they’re about to get some free food.’

‘Who would try to trap me?’

‘You wouldn’t want to find out.’

‘Would you like to fly with me?’ he offered.

‘How do you know I can fly?’

‘Can’t everybody?’ he asked, sounding a bit startled. He was evidently a very young hawk.

To be absolutely honest, though, I enjoyed our flight. Each bird flies a little differently, but the effortless art of soaring, lifted by the unseen columns of warm air rising from the earth, gives one a sense of unbelievable freedom.

All right, I like to fly. So what?

Father had decided to leave me to my own devices that summer, probably because the sound of my voice grated on his nerves. Once, however, he did come to my Tree – probably at Beldaran’s insistence – to try to persuade me to come home. He, however, was the one who got a strong dose of persuasion. I unleashed my birds on him, and they drove him off.

I saw my father and my sister occasionally during the following weeks. In actuality, I stopped by from time to time to see if I could detect any signs of suffering in my sister. If Beldaran was suffering, though, she managed to hide it quite well. Father sat off in one corner during my visits. He seemed to be working on something quite small, but I really wasn’t curious about whatever it might have been.

It was early autumn when I finally discovered what he’d been so meticulously crafting. He came down to my Tree one morning, and Beldaran was with him. ‘I’ve got something for you, Pol,’ he told me.

‘I don’t want it,’ I told him from the safety of my perch.

‘Aren’t you being a little ridiculous, Pol?’ Beldaran suggested.

‘It’s a family trait,’ I replied.

Then father did something he’s very seldom done to me. One moment I was comfortably resting on my perch about twenty feet above the ground. At the next instant I was sprawled in the dirt at his feet. The old rascal had translocated me! That’s better,’ he said. ‘Now we can talk.’ He held out his hand, and there was a silver medallion on a silver chain hanging from his fingers. ‘This is for you,’ he told me.

Somewhat reluctantly I took it. ‘What am I supposed to do with this?’ I asked him.

‘You’re supposed to wear it.’

‘Why?’

‘Because the Master says so. If you want to argue with Him, go right ahead. Just put it on, Pol, and stop all this foolishness. It’s time for us all to grow up.’

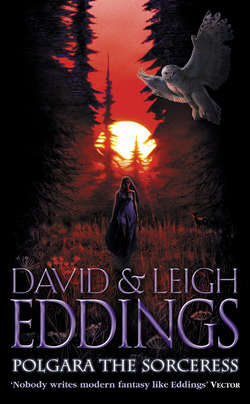

I looked rather closely at the amulet and saw that it bore the image of an owl. It occurred to me that this somehow very appropriate gift had come from Aldur instead of father. At that point in my life decorations of any kind seemed wildly inappropriate, but I immediately saw a use for this one. It bore the image of an owl, my favorite alternative form – and mother’s as well. Part of the difficulty of the shape-change is getting the image right, and father was evidently a very talented sculptor. The owl was so lifelike that it looked almost as if it could fly. This particular ornament would be very useful.

When I put it on, something rather strange came over me. I’d have sooner died than have admitted it, but I suddenly felt complete, as if something had always been missing.

‘And now we are three,’ Beldaran said vapidly.

‘Amazing,’ I said a bit acidly. ‘You do know how to count.’ My unexpected reaction to father’s gift had put me off-balance, and I felt the need to lash out at somebody – anybody.

‘Don’t be nasty,’ Beldaran told me. ‘I know you’re more clever than I am, Pol. You don’t have to hit me over the head with it. Now why don’t you stop all this foolishness and come back home where you belong?’

The guiding principle of my entire life at that point had been my rather conceited belief that nobody told me what to do. Beldaran disabused me of that notion right then and there. She could – and occasionally did – give me orders. The implied threat that she would withhold her love from me brought me to heel immediately.

The three of us walked on back to father’s tower. He seemed a little startled by my sudden change of heart, and I believe that even to this day he doesn’t fully understand the power Beldaran had over me.

Perhaps it was to cover his confusion that he offered me some left-over breakfast. I discovered immediately that this most powerful sorcerer in the world was woefully inadequate in the kitchen. ‘Did you do this to perfectly acceptable food on purpose, father?’ I asked him. ‘You must have. Nobody could have done something this bad by accident.’

‘If you don’t like it, Pol, there’s the kitchen.’

‘Why, I do believe you’re right, father,’ I replied in mock surprise. ‘How strange that I didn’t notice that. Maybe it has something to do with the fact that you’ve got books and scrolls piled all over the working surfaces.’

He shrugged. “They give me something to read while I’m cooking.’

‘I knew that something must have distracted you. You couldn’t have ruined all this food if you’d been paying attention.’ Then I laid my arm on the counter-top and swept all his books and scrolls off on to the floor. ‘From now on, keep your toys out of my kitchen, father. Next time, I’ll burn them.’

‘Your kitchen?’

‘Somebody’s going to have to do the cooking, and you’re so inept that you can’t be trusted near a stove.’

He was too busy picking up his books to answer.

And that established my place in our peculiar little family. I love to cook anyway, so I didn’t mind, but in time I came to wonder if I hadn’t to some degree demeaned myself by taking on the chore of cooking. After a week or so, or three, things settled down, and our positions in the family were firmly established. I complained a bit now and then, but in reality I wasn’t really unhappy about it.

There was something else that I didn’t like, though. I soon found that I couldn’t undo the latch on the amulet father had made for me, but I was something of an expert on latches and I soon worked it out. The secret had to do with time, and it was so complex that I was fairly certain father hadn’t devised it all by himself. He had sculpted the amulet at Aldur’s instruction, after all, and only a God could have conceived of a latch that existed in two different times simultaneously.

Why don’t we just let it go at that? The whole concept still gives me a headache, so I don’t think I’ll go into it any further.

My duties in the kitchen didn’t really fill my days. I soon bullied Beldaran into washing the dishes after breakfast while I prepared lunch, which was usually something cold. A cold lunch never hurt anybody, after all, and once that was done, I was free to return to my Tree and my birds. Neither father nor my sister objected to my daily excursions, since it cut down on my opportunities to direct clever remarks at father.

And so the seasons turned, as they have a habit of doing.

We were pretty well settled in after the first year or so, and father had invited his brothers over for supper. I recall that evening rather vividly, since it opened my eyes to something I wasn’t fully prepared to accept. I’d always taken it as a given that my uncles had good sense, but they treated my disreputable father as if he were some sort of minor deity. I was in the midst of preparing a fairly lavish supper when I finally realized just how much they deferred to him.

I forget exactly what they were talking about – Ctuchik, maybe, or perhaps it was Zedar – but uncle Beldin rather casually asked my father, ‘What do you think, Belgarath? You’re first disciple, after all, so you know the Master’s mind better than we do.’

Father grunted sourly. ‘And if it turns out that I’m wrong, you’ll throw it in my teeth, won’t you?’

‘Naturally.’ Beldin grinned at him. ‘That’s one of the joys of being a subordinate, isn’t it?’

‘I hate you,’ Father said.

‘No you don’t, Belgarath,’ Beldin said, his grin growing even broader. ‘You’re just saying that to make me feel better.’

I can’t count the number of times I’ve heard that particular exchange between those two. They always seem to think it’s hilarious for some reason.

The following morning I went on down to my Tree to ponder this peculiar behavior on the part of my uncles. Evidently father had done some fairly spectacular things in the dim past. My feelings about him were uncomplimentary, to say the very least. In my eyes he was lazy, more than a bit silly, and highly unreliable. I dimly began to realize that my father is a very complex being. On the one hand, he’s a liar, a thief, a lecher, and a drunkard. On the other, however, he’s Aldur’s first disciple, and he can quite possibly stop the sun in its orbit if he wants to. I’d been deliberately seeing only his foolish side because of my jealousy. Now I had to come to grips with the other side of him, and I deeply resented the shattering of my illusions about him.

I began to watch him more closely after I returned home that day, hoping that I could find some hints about his duality – and even more fervently hoping that I could not. Losing the basis for one’s prejudices is always very painful. All I really saw, though, was a rather seedy-looking old man intently studying a parchment scroll.

‘Don’t do that, Polgara,’ he said, not even bothering to look up from his scroll.

‘Do what?’

‘Stare at me like that.’

‘How did you know I was staring?’

‘I could feel it, Pol. Now stop.’

That shook my certainty about him more than I cared to admit. Evidently Beldin and the twins were right. There were a number of very unusual things about my father. I decided I’d better have a talk with mother about this.

‘He’s a wolf, Pol,’ mother told me, ‘and wolves play. You take life far too seriously, and his playing irritates you. He can be very serious when it’s necessary, but when it’s not, he plays. It’s the way of wolves.’

‘But he demeans himself so much with all that foolishness.’

‘Doesn’t your particular foolishness demean you? You’re far too somber, Pol. Learn how to smile and to have some fun once in a while.’

‘Life is serious, mother.’

‘I know, but it’s also supposed to be fun. Learn how to enjoy life from your father, Polgara. There’ll be plenty of time to weep, but you have to laugh as well.’

Mother’s tolerance troubled me a great deal, and I found her observations about my nature even more troubling.

I’ve had a great deal of experience with adolescents over the centuries, and I’ve discovered that as a group these awkward half-children take themselves far too seriously. Moreover, appearance is everything for the adolescent. I suppose it’s a form of play-acting. The adolescent knows that the child is lurking just under the surface, but he’d sooner die than let it out, and I was no different. I was so intent on being ‘grown-up’ that I simply couldn’t relax and enjoy life.

Most people go through this stage and outgrow it. Many, however, do not. The pose becomes more important than reality, and these poor creatures become hollow people, forever striving to fit themselves into an impossible mold.

Enough. I’m not going to turn this into a treatise on the ins and outs of human development. Until a person learns to laugh at himself, though, his life will be a tragedy – at least that’s the way he’ll see it.

The seasons continued their stately march, and the little lecture mother had delivered to me lessened my interior antagonism toward father. I did maintain my exterior facade, however. I certainly didn’t want the old fool to start thinking I’d gone soft on him.

And then, shortly after my sister and I turned sixteen, the Master paid my father a call and gave him some rather specific instructions. One of us – either Beldaran or myself – was to become the wife of Iron-grip and hence the Rivan Queen. Father, with rather uncharacteristic wisdom, chose to keep the visit to himself. Although I certainly had no particular interest in marrying at that stage of my life, my enthusiasm for competition might have led me into all sorts of foolishness.

My father quite candidly admits that he was sorely tempted to get rid of me by the simple expedient of marrying me off to poor Riva. The Purpose – Destiny, if you wish – which guides us all prevented that, however. Beldaran had been preparing for her marriage to Iron-grip since before she was born. Quite obviously, I hadn’t been.

I resented my rejection, though. Isn’t that idiotic? I’d been involved in a competition for a prize I didn’t want, but when I lost the competition, I felt the sting of losing quite profoundly. I didn’t even speak to my father for several weeks, and I was even terribly snippy with my sister.

Then Anrak came down into the Vale to fetch us. With the exception of an occasional Ulgo and a few messengers from King Algar, Anrak was perhaps the first outsider I’d ever met and certainly the first whoever showed any interest in me. I rather liked him, actually. Of course he did propose marriage to me, and a girl always has a soft spot in her heart for the young man who asks her for the first time. Anrak was an Alorn, with all that implies. He was big, burly, and bearded, and there was good-humored simplicity about him that I rather liked. I didn’t like the way he always reeked of beer, however.

I was busy sulking in my Tree when he arrived, so we didn’t even have time to get acquainted before he proposed. He came swaggering down the Vale one beautiful morning in early spring. My birds alerted me to his approach, so he didn’t really surprise me when he came in under the branches of my Tree.

‘Hello, up there,’ he called to me.

I looked down from my perch at him. ‘What do you want?’ It wasn’t really a very gracious greeting.

‘I’m Anrak – Riva’s cousin – and I came here to escort your sister to the Isle so Riva can marry her.’

That immediately put him in the camp of the enemy. ‘Go away,’ I told him bluntly.

There’s something I need to ask you first.’

‘What?’

‘Well, like I said, I’m Riva’s cousin, and he and I usually do things together. We got drunk together for the first time, and visited a brothel together for the first time, and even both killed our first man in the same battle, so as you can see, we’re fairly close.’

‘So?’

‘Well, Riva’s going to marry your sister, and I thought it might be sort of nice if I got married, too. What do you say?’

‘Are you proposing marriage to me?’

‘I thought I said that. This is the first time I’ve ever proposed to anybody, so I probably didn’t do a very good job. What do you think?’

‘I think you’re insane. We don’t even know each other.’

‘There’ll be plenty of time for us to get to know each other after the ceremony. Well, yes or no?’

You couldn’t fault Anrak’s directness. Here was a man who got right down to the point. I laughed at him, and he looked just a bit injured by that. ‘What’s so funny?’ he demanded in a hurt tone of voice.

‘You are. Do you actually think I’d marry a complete stranger? One who looks like a rat hiding in a clump of bushes?’

‘What’s that supposed to mean?’

‘You’ve got hair growing all over your face.’

‘That’s my beard. All Alorns wear beards.’

‘Could that possibly be because Alorns haven’t invented the razor yet? Tell me, Anrak, have your people come up with the idea of the wheel yet? Have you discovered fire, by any chance?’

‘You don’t have to be insulting. Just say yes or no.’

‘All right. No! Was there any part of that you didn’t understand?’ Then I warmed to my subject. The whole notion is absurd,’ I told him. ‘I don’t know you, and I don’t like you. I don’t know your cousin, and I don’t like him either. As a matter of fact, I don’t like your entire stinking race. All the misery in my life’s been caused by Alorns. Did you really think I’d actually marry one? You’d better get away from me, Anrak, because if you don’t, I’ll turn you into a toad.’

‘You don’t have to get nasty. You’re no prize yourself, you know.’

I won’t repeat what I said to him then – this document might just fall into the hands of children. I spoke at some length about his parents, his extended family, his race, his ancestors and probable descendants. I drew rather heavily on uncle Beldin’s vocabulary in the process, and Anrak frequently looked startled at the extent of my command of the more colorful side of language.

‘Well,’ he said, ‘if that’s the way you feel about it, there’s not much point in our continuing this conversation, is there?’ And then he rather huffily turned and strode back up the Vale, muttering to himself.

Poor Anrak. I was feeling a towering resentment over the fact that some unknown Alorn was going to take my sister away from me, and so he had the privilege of receiving the full weight of my displeasure. Moreover, mother’d strongly advised me to steer clear of any lasting entanglements at this stage of my life. Adolescent girls have glandular problems that sometimes lead them to make serious mistakes.

Why don’t we just let it go at that?

I had absolutely no intention of going to the Isle of the Winds to witness this obscene ceremony. If Beldaran wanted to marry this Alorn butcher, she was going to have to do it without my blessing – or my presence.

When they were ready to leave, however, my sister came down to my Tree and ‘persuaded’ me to change my mind. Despite that sweet exterior that deceived everyone else, my sister Beldaran could be absolutely ruthless when she wanted something. She knew me better than anyone else in the world did – or could – so she knew exactly where all my soft spots were. To begin with, she spoke to me exclusively in ‘twin’, a language I’d almost forgotten. There were subtleties in ‘twin’ – mostly of Beldaran’s devising – that no linguist, even the most gifted, could ever unravel, and most of them stressed her dominant position. Beldaran was accustomed to giving me orders, and I was accustomed to obeying. Her ‘persuasion’ in this situation was, to put it honestly, brutal. She reminded me of every time in our lives when we’d been particularly close, and she cast those reminders in a past tense peculiar to our private tongue that would more or less translate into ‘never again’, or ‘over and done with’. She had me in tears within five minutes and in utter anguish within ten. ‘Stop!’ I cried out finally, unable to bear the implicit threat of a permanent severing of all contact any longer.

‘You’ll come with me then?’ she asked, reverting to ordinary speech.

‘Yes! Yes! Yes! But please stop!’

‘I’m so happy about your decision, Pol,’ she said, embracing me warmly. Then she actually apologized for what she’d just done to me. Why not? She’d just won, so she could afford to be graceful about the whole thing.

I was beaten, and I knew it. I wasn’t even particularly surprised to discover when Beldaran and I returned to father’s tower that she’d already packed for me. She’d known all along just how things would turn out.

We set out the next morning. It took us several weeks to reach Muros, since we traveled on foot.

Beldaran and I were both uneasy in Muros, since we’d never really been around that many people before. Although I’ve changed my position a great deal since then, at first I found Sendars to be a noisy people, and they seemed to me to have a positive obsession with buying and selling that was almost laughable.

Anrak left us at Muros to go on ahead to advise Riva that we were coming. We hired a carriage, and the four of us, father, uncle Beldin, Beldaran and I rode the rest of the way to Camaar. Frankly, I’d have rather walked. The stubby ponies drawing the carriage didn’t really move very fast, and the wheels of the carriage seemed to find every single rock and rut in the road. Riding in carriages didn’t really become pleasant until some clever fellow came up with a way to install springs in them.

Camaar was even more crowded with people than Muros had been. We took some rooms in a Sendarian inn and settled down to wait for Riva’s arrival. I found it rather disconcerting to see buildings every time I looked out the window. Sendars appeared to have a kind of revulsion to open spaces. They always seem to want to ‘civilize’ everything.

The innkeeper’s wife, a plump, motherly little woman, seemed bent on ‘civilizing’ me as well. She kept offering me the use of the bath-house, for one thing. She rather delicately suggested that I didn’t smell very sweet.

I shrugged off her suggestions. ‘It’s a waste of time,’ I told her. ‘I’ll only get dirty again. The next time it rains, I’ll go outside. That should take the smell and the worst of the dirt off me.’

She also offered me a comb and a brush – which I also refused. I wasn’t going to let the Alorn who’d stolen my sister away from me get some idea that I was taking any pains to make myself presentable for his sake.

The nosey innkeeper’s wife then went so far as to suggest a visit to a dressmaker. I wasn’t particularly impressed by the fact that we’d shortly be entertaining a king, but she was.

‘What’s wrong with what I’m wearing?’ I asked her pugnaciously.

‘Different occasions require different clothing, dear,’ she replied.

‘Foolishness,’ I said. ‘I’ll get a new smock when this one wears out.’

I think she gave up at that point. I’m sure she thought I was incorrigibly ‘woodsy’, one of those unfortunates who’ve never received the benefits of civilization.

And then Anrak brought Riva to our rooms. I’ll grant that he was physically impressive. I don’t know that I’ve ever seen anyone – except the other men in his family – quite so tall. He had blue eyes and a black beard, and I hated him. He muttered a brief greeting to my father, and then he sat down to look at Beldaran.

Beldaran looked right back.

It was probably the most painful afternoon I’d spent in my entire life up until then. I’d hoped that Riva would be more like his cousin, Anrak, blurting out things that would offend my sister, but the idiot wouldn’t say anything! All he could do was look at her with that adoring expression on his face, and Beldaran was almost as bad in her obvious adoration of him.

I was definitely fighting a rear-guard action here.

We all sat in absolute silence watching them adore each other, and every moment was like a knife in my heart. I’d lost my sister, there wasn’t much question about that. I wasn’t going to give either of them the satisfaction of seeing me bleed openly, however, so I did all of my bleeding inside. It was quite obvious that the separation of Beldaran and me which had begun before we were ever born was now complete, and I wanted to die.

Finally, when it was almost evening, my last hope died, and I felt tears burning my eyes.

Rather oddly – I hadn’t been exactly polite to him – it was father who rescued me. He came over and took my hand. ‘Why don’t we take a little walk, Pol?’ he suggested gently. Despite my suffering, his compassion startled me. He was the last one in the world I’d have expected that from. My father does surprise me now and then.

He led me from the room, and I noticed as we left that Beldaran didn’t even take her eyes off Riva’s face as I went away. That was the final blow, I think.

Father took me down the hallway to the little balcony at the far end, and we went outside, closing the door behind us.

I tried my very best to keep my sense of loss under control. ‘Well,’ I said in my most matter-of-fact way, ‘I guess that settles that, doesn’t it?’

Father murmured some platitudes about destiny, but I wasn’t really listening to him. Destiny be hanged! I’d just lost my sister! Finally, I couldn’t hold it in any longer. With a wail I threw my arms around his neck and buried my face in his chest, weeping uncontrollably.

That went on for quite some time until I’d finally wept myself out. Then I got my composure back. I decided that I wouldn’t ever let Riva or Beldaran see me suffering, and, moreover, that I’d take some positive steps to show them that I really didn’t care that my sister was willingly deserting me. I questioned father about some things that wouldn’t have concerned me before – baths, dressmakers, combs, and the like. I’d show my sister how little I really cared. If I was suffering, I’d make sure that she suffered too.

I took particular pains with my bath. In my eyes this was a sort of funeral – mine – and it was only proper that I should look my best when they laid me out. My chewed off fingernails gave me a bit of concern at first, but then I remembered our gift. I concentrated on my nails and then said, ‘Grow.’

And that took care of that.

Then I luxuriated for almost an hour in my bath. I wanted to soak off all the accumulated dirt, certainly, but I was surprised to discover that bathing felt good.

When I climbed out of the barrel-like wooden tub, I toweled myself down, put on a robe, and sat down to deal with my hair. It wasn’t easy. My hair hadn’t been washed since the last rain-storm in the Vale, and it was so tangled and snarled that I almost gave up on it. It took a lot of effort, and it was very painful, but at last I managed to get it to the point where I could pull a comb through it.

I didn’t sleep very much that night, and I arose early to continue my preparations. I sat down in front of a mirror made of polished brass and looked at my reflection rather critically. I was somewhat astonished to discover that I wasn’t nearly as ugly as I’d always imagined. As a matter of fact, I was quite pretty.

‘Don’t let it go your head, Pol,’ mother’s voice told me. ‘You didn’t actually think that I’d give birth to an ugly daughter, did you?’

‘I’ve always thought I was hideous, mother,’ I said.

‘You were wrong. Don’t overdo it with your hair. The white lock doesn’t need any help to make you pretty.’

The blue dress father’d obtained for me was really quite nice. I put it on and looked at myself in the mirror. I was just a little embarrassed by what I saw. There wasn’t any question that I was a woman. I’d been more or less ignoring certain evidences of my femaleness, but that was no longer really possible. The dress positively screamed the fact. There was a problem with the shoes, though. They had pointed toes and medium heels, and they hurt my feet. I wasn’t used to shoes, but I gritted my teeth and endured them.

The more I looked in my mirror, the more I liked what I saw. The worm I’d always been had just turned into a butterfly. I still hated Riva, but my hatred softened just a bit. He hadn’t intended it, but it was his arrival in Camaar that had revealed to me what I really was.

I was pretty! I was something even beyond pretty!

‘What an amazing thing,’ I murmured.

My victory was made complete that morning when I demurely – I’d practiced for a couple of hours – entered the room where the others were sitting. I’d more or less taken the reactions of Riva and Anrak for granted. Uneducated though I was, I knew how they’d view me in my altered condition. The face I looked at was Beldaran’s.

I’d rather hoped to see just a twinge of envy there, but I should have known better. Her expression was just a little quizzical, and when she spoke, it was in ‘twin’. What passed between us was intensely private. ‘Well, finally,’ was all she said, and then she embraced me warmly.