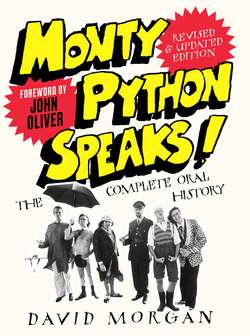

Читать книгу Monty Python Speaks! Revised and Updated Edition: The Complete Oral History - David Morgan - Страница 21

PERT PIECES OF COPPER COINAGE

ОглавлениеJONES: I think our budget was £5,000 a show. It had been kind of a tight operation. Everything was planned very rigorously. We’d do the outdoor filming for most of the series before we started shooting the studio stuff. We had to write the entire series before we even started doing anything because we’d be shooting stuff for show 13, show 1, or show 2 while we’re in one location, so that while you’re at the seaside you can do all the seaside bits.

PALIN: A lot of the early arguments were just over money; we were paid so incredibly little. So in a sense the BBC committed a lot, they’d given us thirteen shows (which was nice), but they’d taken away with one hand what they’d given us with the other. But on the other hand they let us go ahead and do it!

MACNAUGHTON: Because I was the producer as well as the director, I was able to speak as a producer, so I could say [to the Pythons], ‘That is impossible, we have only got so much of a budget; can we alter this slightly to allow that we don’t go too far over?’ Because you know at the BBC in those days if you went too far over budget the people got rather anarchic. Unless you were exceptionally successful.

PALIN: We presented a script to Ian, we knew what we wanted to do on film and what should be done in the studio, and Ian didn’t really get involved in that aspect of it. On the other hand when we were discussing things like where we would film and how we could best get the effect of a piece of film he would have quite a bit of input. And we’d actually film in Yorkshire and Scotland – that was very often Ian saying, ‘Let’s go out and do that.’

MACNAUGHTON: We used to plan about eight weeks in advance of the series. We knew we wanted an average of, say, five minutes of film per episode (in the first series anyway). The series was thirteen, so we needed time to [shoot] an hour and a half of film. We would plan what sketches or what sequences were better filmed than done in the studio, etc. And as the Pythons went on, they got more interested in the filming side than in the studio side.

Nothing was too ridiculous for us to try. You have a silly sketch like ‘Spot the Loony’ and you happen to be up in Scotland shooting ‘Njorl’s Saga’, and you suddenly think, ‘Wouldn’t it be good to have the loony here in the middle of Glen Coe leaping through the thing?’ These kinds of things happened. They enjoyed all that kind of thing. And it was not particularly more expensive than filming, say, in London because the permission and the fees we had to pay in filming in Glen Coe or Oban or whatever were much less than what we had to pay at the Lower Courts or Cheapside. So the expense was not so great, [and] the opulence of the locations was there, you didn’t have to build them!

GILLIAM: We weren’t doing drama, we were doing comedy, which fell under Light Entertainment, and light seemed to be required constantly so that you could see the joke! Feel the joke! And I just always had a stronger visual sense than [what] we were able to get on those filmings. There would be all these times I’d get in there: ‘The camera should be there.’ Terry would do the same thing; we were always pushing Ian around! I think we were just frustrated because we wanted to film this, too; we were convinced we could do it better. But the BBC didn’t work that way. They would put a producer/director on the thing. And there was a kind of Light Entertainment direction at the BBC which was very sort of sloppy.

I was always frustrated because it didn’t look as good as it should; the lighting wasn’t as good as it should have been. Everything was done so fast and shoddily, there was very little time to get real atmosphere on the screen, or to shoot it dramatically enough or exciting enough. But you churned it out; it’s the nature of television.

We wanted it to look like Drama as opposed to Light Entertainment. Drama was serious; that’s where the real talents hung out!

They ate at a separate canteen?

GILLIAM: It’s almost like that, it always felt like that; they had more money, they can light this stuff. If you’ve got something beautifully lit and the costumes are really great and the set’s looking good and then you do some absurd nonsense, it’s funnier than having it in a cardboard set with some broad lighting. And especially since a lot of the stuff would be parodies of things – if you’re going to do a parody, it’s got to look like the original.

So when we were able to do Holy Grail and direct it ourselves, it looked a lot better. I think the jokes were funnier because the world was believable, as opposed to some cheap LE lightweight. I mean, we approached Grail as seriously as Pasolini did. We were watching the Pasolini films a lot at that time because he more than anybody seemed to be able to capture a place and period in a very simple but really effective way. It wasn’t El Cid and the big epics, it was much smaller. You could feel it, you could smell it, you could hear it.

JONES: Poor old Ian had me [to deal with]. I insisted on going on the location scouts with him and then when we were filming was really sitting in and seeing what Ian was doing all the time. And it was awful for me, too; I used to go out with this terrible tight stomach because we’d see Ian put the camera down and I’d think, ‘It’s in the wrong place, it should be over there!’ So I’d have to go up to Ian very quietly and sort of say, ‘Ian, don’t you think you should put it over there?’ or something like that, and then depending on Ian’s mood at the time, because if it were morning when he hadn’t been drinking he would be very good, but sometimes he got a bit shirty.

Obviously when we were in the studio on the floor you can’t do very much, so Ian had his head then. But in the editing I’d always ring Ian up and say, ‘When’s the editing?’ I could see Ian going, Jesus Christ! Sort of tell me between gritted teeth, and then I’d turn up.

Did he ever purposely tell you the wrong time, to put you off?

JONES: I get the feeling he wanted to do that, but he was too honourable a man! Especially at the beginning, I’d turn up and he’d say, ‘Look, we’ve only got two hours to do this in.’ And I just had to shut out of my head everything about that and say, ‘Well, let’s just see how long.’ We’d end up doing the whole day. I’d see something and I’d think, ‘Ian, we have to take that out, there’s a gap there.’ Usually it was cutting things out, and closing up the show so that it went fast. But it was very hard, because every time I wanted to change something, my stomach would go tight because I knew Ian would go, ‘We’ve nearly had two hours now and we’ve only done ten minutes!’ So we got on a bit like that. And then at the end of the day I’d ring everybody up to have a look at the show. But then as it went on Ian really got very good, actually, because although it was a bit sticky in the first series – and it shows, I think; the first series is not edited as tightly as it could have been – as it went on, Ian got really good at it, and realized that I wasn’t trying to muscle in on his thing; we were just trying to make the best show possible, making sure the material actually came over. So it was very hard for him, but eventually the relationship got really good, and Ian and I worked really well. Ian got very creative, and once you relaxed he got very creative about it, and then came up with a lot of different stuff.