Читать книгу Monty Python Speaks! Revised and Updated Edition: The Complete Oral History - David Morgan - Страница 22

TEN, NINE, EIGHT AND ALL THAT

ОглавлениеCLEESE: My memory is that on the whole Ian did not, let’s be polite, interfere much with the acting! We tended to watch each other’s stuff – not all the time because a certain amount of rehearsal is just practice, but we would keep an eye on each other’s sketches, and at a suitable moment somebody might suggest an additional line, or we might come forward and say, ‘I think that bit isn’t working.’ But there was such an instinctive understanding within the group that you probably didn’t even have to say that because people would already know it wasn’t working. It was very much a group activity – not that we were all sitting around desperately focused on each other’s sketches, because people sat around and read the paper and wrote up their diaries.

MACNAUGHTON: We did the usual BBC style of five or six days’ rehearsal. On the sixth day there would be a technical run-through for all the lighting, etc., and then we were one day in the studio. And of course all the stuff we had filmed we showed to the audience in the studio as we did each episode.

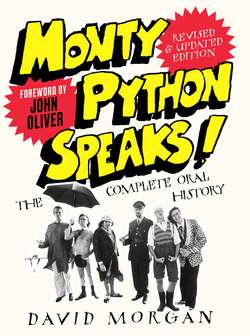

Cleese and Idle in rehearsal, c. 1971.

From the beginning I had no problem working with them because they’re extremely disciplined as actors, as comic actors.

We honestly had a very good working relationship. I have never from the beginning had one problem with any of them. I felt myself to be a part of the team anyway.

I can remember one time John looking at me after a sketch had been done and saying, ‘Why aren’t you laughing?’ And I said, ‘Well, there’s something not quite right with this sketch.’ He said, ‘You hear that, gentlemen? Let’s do it again.’ They did it again, and he said, ‘No, I think we’ll find a new one,’ and did a new one the next day.

I can’t remember any explosions. Come the second series there was one moment and that was quite fun: we were making the film ‘The Bishop’, and I’d set up the opening shot with a lower-level camera. The bishop’s car raced up to the camera, stopped, out jumped all the mafia bishops, etc., and ran up to the church. Now Terry Jones said to me, ‘No, no, you must do this in a high angle.’ And I said, ‘No, I think the low angle’s better for this opening,’ knowing what had gone before. ‘No, no, no!’ We had a bit of a row, and we walked off together, Terry kicking stones right and left. And I said, ‘Look, Terry, just leave it for a moment – anyway, I haven’t got a cherry picker with me and can’t get the big high angle that you’re looking for.’ We came back and did it. We then went on another location in Norwich I think it was, and where we saw the rushes from the previous week, up came the rushes for ‘The Bishop’ – and this is what’s so nice about the whole group: Terry Jones turned around in the hotel’s dining room where we were watching the rushes, held his thumb up to me, and said, ‘You were right, it worked perfectly.’ And that is I think the biggest row we ever had, and it’s not a very big one, you must admit.

JONES: In studio, we tried to do it sequentially as much as we could. It was a bit stop-and-starty sometimes, but we tried as much as we could to rush through the costume changes. We only had an hour and a half recording time anyway, so you had thirty-five minutes of material to record. We very often did it as a live show with just a few hitches, try and keep the momentum going to keep the audience entertained. We didn’t want to stop the show because it meant the audience going off the boil a bit.

MACNAUGHTON: We had a studio audience of 320; that was a BBC policy, to have a studio audience. And you know, never had we laid a laugh from a laugh track on Python. It was a kind of policy, because we thought if the audience don’t really like it, they won’t laugh anyway, and there’s nothing worse than listening to shows that have laugh tracks on and the audience is roaring with laughter at something you’ve found totally unfunny yourself.

JONES: For me, when we came to the editing the audience was always the great key – we always had that laughter to go by so you knew whether something was working or not. And if something didn’t get a laugh, then we cut it. A lot of the time we were actually having to take laughs out because it was holding up the shows.

I remember one show that didn’t seem to work in the studio, and that was ‘The Cycling Tour’. Everybody came out very disappointed, all the audience and our friends going, ‘Eh, that wasn’t very good, didn’t really work, that.’ And of course the trouble with that was that it wasn’t shot sequentially, or even when it was shot sequentially it was very stop-and-starty. Like all the stuff in the hospital, the casualty ward, was very quick cuts – a sign falling off, a trolley collapsing, a window falling on somebody’s hand – that all had to be shot separately, so they didn’t seem very funny at the time. But when you cut them in very fast, that made it seem quite funny.

MACNAUGHTON: At the beginning they all wanted to come to the editing, and I said, ‘That’s no use, we can’t have five guys standing around me standing around the editor.’ So in the end only Terry used to come to the editing. We’d sit together and we’d say, ‘Yes, I think cut there,’ and ‘No, I think it should be cut later,’ and ‘No, I’m sorry, I think it’s quicker’ – the usual thing. There were honestly no problems.

GILLIAM: Terry tended to be the one to be in the editing room, sitting looking over Ian’s shoulder, and keeping an eye on things. I popped in occasionally, John, different people. Terry was almost always there.

Ian dealt with the BBC, basically; we didn’t have to. That’s the great thing about the BBC, it’s not like American television; once they said ‘Go’, they basically left. It was a real, incredibly laissez-faire operation. That was the strength of the place, because it just allowed the talent to get on to do what it did. And in the end the talent ended up producing more good material than all these meetings are producing now. I don’t think the batting average is any better now than it was then, it’s actually worse, and they all end up sitting around talking things to death. It was very simple: you’ve got this series, we want seven shows now and six later and you do it, that’s it.

We had freedom like nobody gets now, basically. And the only time we started getting some involvement from them was later on, I think it was probably the third series, because as we’d become successful they felt that they had to interfere in some way, to be involved in this thing.