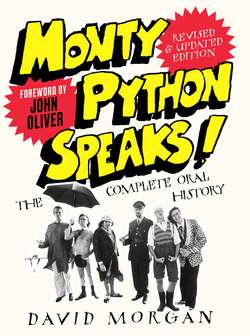

Читать книгу Monty Python Speaks! Revised and Updated Edition: The Complete Oral History - David Morgan - Страница 30

SPLUNGE!

ОглавлениеI’d Like to Answer This Question If I May in Two Ways: Firstly in My Normal Voice and Then in a Kind of Silly, High-Pitched Whine

JONES: I always loved Graham as a performer, from when I first saw him in Cambridge Circus and then in At Last the 1948 Show, because you could never quite see what he was doing. I mean, John I dearly love as a performer, but from the moment you first see John you know where John is; Graham was always very intangible.

I think Graham always played everything as if he didn’t think anything was funny, [as if] he didn’t see the joke in anything, really, which was just wonderful. Which was why he worked for the leads in Holy Grail and Life of Brian, because he played it so straight and sincerely and seriously.

PALIN: The characters that Graham played were again great Establishment characters. He would play a colonel exactly right and add this wonderful mad streak throughout. I think Graham took more risks than John, and I think when they wrote together, although John I’m sure put together 80 per cent of their sketches, the 20 per cent that Graham put in was the truly surreal and extraordinary. Graham had a wonderful gift with words; I’m sure ‘Norwegian Blue’ for a parrot would be Graham’s. There’s something about it: a Norwegian Blue parrot – that just sounds like Graham.

Graham as a performer had a quiet intensity which, if you look at all of his performances, quite unlike any of the rest of us, is very convincing whatever he does. That’s why he was so good as Brian, so good as Arthur; here was a man who genuinely suffered, you know, trying to get through this world – he just happened to be a king, it wasn’t his fault – he was trying to do his best, and all these people around him were just mucking him up. One really felt for him. Graham could portray that very well, partly because I think he was a little nervous as a performer, because he took to drink at one time. By Life of Brian he had given it up, and he didn’t need that, but he was always slightly nervous about it. There’s a concentration in the way Graham does things which looks good, it comes across as very natural and very right.

CLEESE: Graham was fundamentally a very, very fine actor. He could do very odd things, like mime, and he did a very funny impression of the noise made by an espresso machine, things like that. He was a really, really good actor. But to understand Graham you have to realize he didn’t really work properly. If he was a little machine, you would take him back and somebody would fiddle with it, and then it would come back working properly. So he was a very odd man; he was in many ways highly intelligent and quite insightful, in other ways he was a complete child, and not someone who was really any good at taking any sort of responsibility and discharging it.

His best function, and the reason that I wrote with him all those years, is that we got on pretty well. We laughed at the same things, we made each other laugh. And he was the greatest sounding board that I ever worked with. When Graham laughed or thought something funny, he was nearly always right, and that’s extraordinary. For example: when we were writing the ‘Cheese Shop’ [sketch], I kept saying to him, ‘Is this funny? Is this funny?’ And he’d go, [puff puff on his pipe] ‘It’s funny, go on.’ And that’s really how the ‘Cheese Shop’ [sketch] was written as opposed to just being abandoned, because I kept having my doubts. He was a wonderful sounding-board.

And the other side of that was that he was very disorganized – I mean we were all a bit disorganized, but he was really disorganized, and really fundamentally very lazy. His input was minimal; I remember working with Kevin Billington on a movie that turned out to be called The Rise and Rise of Michael Rimmer. After a couple of sessions, Kevin said to me very quietly, perhaps on a lunch break when Graham had gone to the bathroom, ‘Does Graham usually make so little contribution?’ And I remember being quite surprised by the question, because I’d got used to the fact that he made so little contribution.

He didn’t say very much, but when he did say something it was often very good. But he was never the engine; someone had to be in the engine room driving something forward, and then Graham would sit there and add the new thought or twist here or there, which is terribly useful. But I remember saying to somebody once that there were two kinds of days with Graham; there were the days when I did 80 per cent of the work, and there were the days when he did 5 per cent of the work.

To give you a real example of how bad it could be: when we finished the first series of The Frost Report in 1966, David Frost gave us £1,000 to write a movie script. With the money we went off to Ibiza, and we took a villa for two months and decided to write there, and a whole lot of friends came and stayed with us and passed through, and that is when Graham met David Sherlock. I remember that I would sit inside at the desk writing, and Graham would literally be lying on the balcony outside sunbathing, calling suggestions into the room as I sat there writing.

And the funny thing is I don’t remember being cross about it; I think I just accepted that writing with Graham I was going to have to do 80 per cent of the work and sometimes more. And it always slightly annoyed me when people used to come up to me on Fawlty Towers and say, ‘Well, how much did Connie Booth actually write?’ And I wanted to say to them, ‘Certainly a lot more than Graham ever wrote.’ That used to annoy me, the assumption that because Graham was a man he was obviously making a bigger contribution than Connie as a woman.

SHERLOCK: Graham would have been a very good shrink, because if nothing else he understood what made people tick. And if he couldn’t understand, he would make it his job to find out. And his interview technique, if he was looking for prospective interesting people wanting to join his coterie, within five minutes he could sum somebody up and sort them out.

However, I think he was far less astute financially than Cleese, who had a great many friends who were accountants – hence a lot of the sketches! – but he learned from them. Sadly those sort of people bored Graham, I don’t think he was even interested [in connecting]. That’s why he lost money while others were gaining.

One of the most delightful sounds I’ve ever heard was Graham and John writing. This was in the days when we lived in Highgate in the Seventies. I would often be preparing food for our large nuclear family (who could be anything from three to four to ten on an evening sometimes, depending on who Graham invited back from the pub or whatever). Part of my life consisted of keeping the household kicking over. I didn’t do it very well, but it was fairly Bohemian anyway, so it didn’t matter too much. But in the morning if I was making coffee for them, I would often hear a delighted shriek as they hit on some outrageous idea, often followed by the thudding of bodies hitting the floor, and the drumming of feet like a child with a tantrum, only this was the sheer delight of the idiocy