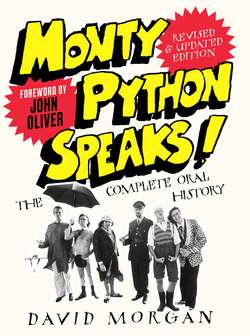

Читать книгу Monty Python Speaks! Revised and Updated Edition: The Complete Oral History - David Morgan - Страница 23

WHY DON’T YOU MOVE INTO MORE CONVENTIONAL AREAS?

ОглавлениеPALIN: I think there was always a conscious desire to do something which was ahead of or tested the audience’s taste, or tested the limits of what we can or cannot say. I think it’s probably strongest in John and Graham’s writing; they enjoyed being able to shock, whereas Terry and I enjoyed surprise more than shock. For us it was more putting together odd and surreal images in a certain way which would not offend but really jolt, surprise, and amaze. John and Graham took some pleasure in writing something which shocked an audience. I think this came from within, but John never seemed to be totally happy or centred – there was always something which John was having to cope with. And that desire to shock I think came from the way Graham was, too. Graham was a genuine outsider, a very strait-laced man who was homosexual and an alcoholic at that time and therefore found himself constantly in conflict with people, and so he would fight back. And the two of them would put together things like the ‘Undertaker Sketch’ purely because they knew it was outrageous, and yet they did it in a way none of the other Pythons would have done, so it was quite refreshing. When we first heard that we thought, ‘Well, we just can’t do it.’ But then you think about it: this is a really good, refreshing view of death, talking about it that way. In that particular case I think yes, there was a desire to shock an audience by talking about something that was not talked about.

Terry and I were not quite so interested in taboos.

Was it because, having been journeymen scriptwriters for hire, your previous experience did not allow for taboo material?

If you had written taboo material for others, you wouldn’t have got hired again.

PALIN: No, I don’t think that’s it, I think it just wasn’t in our nature to write deliberately shocking material; we couldn’t make it very funny. We could surprise, we could amaze. It was personal, it was nothing to do with our writing; in fact, quite the opposite: the writing that we had to do in the Sixties made us relish Python and the freedom Python had. We utterly supported John and Graham and what they were writing, and for us it was all part of the freedom of Python: to do stuff we wouldn’t have been able to do as journeymen writers. Great, someone writes a sketch about undertakers; it seemed shocking to start with it, you look at it and say, ‘Okay, let’s give this a go.’ And that was part of the exhilaration of doing Python. But no, I don’t think Terry and myself were particularly good about getting laughs [from] very abrasive material. There might have been instances, I can’t remember, [but] we were more about human behaviour, moralizing.

SHERLOCK: Cleese as he’s got older has become more conservative, but when they first started out Python was really quite left-wing; it was considered by some to be commie and subversive.

IDLE: Always we tried to épater les bourgeois.

Once when filming, a British middle-class lady came up and said, ‘Oh, Monty Python; I absolutely hate you lot.’ And we felt quite proud and happy. Nowadays I miss people who hate us; we have sadly become nice, safe, and acceptable now, which shows how clever an Establishment really is, opening up to make room inside itself.