Читать книгу Monarchy: From the Middle Ages to Modernity - David Starkey - Страница 21

SHADOW OF THE KING

ОглавлениеEDWARD VI, MARY I , ELIZABETH I

IN 1544 KING HENRY VIII, now in the third decade of his reign, bestrode England like an ageing colossus. By making himself Supreme Head of the Church of England he had taken the monarchy to the peak of its power. But at a huge personal cost.

For the supremacy had been born out of Henry’s desperate search for an heir and love. The turmoil of six marriages, two divorces, two executions and a tragic bereavement had produced three children by these different and mutually hostile mothers. It was a fractured and unhappy royal family. Now the king felt it was time for reconciliation.

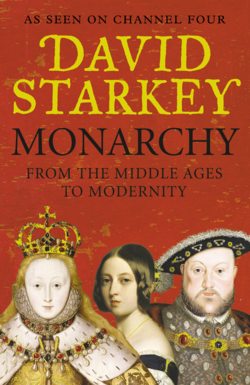

Henry’s reunion with his family is commemorated in a famous painting, known as ‘The Family of Henry VIII’. The painting shows Henry enthroned between his son and heir, the seven-year-old Edward, and, to emphasize the line of dynastic succession, Edward’s long-dead mother Jane Seymour. Standing farther off to the right is Henry’s elder daughter Mary, whom he bastardized when he divorced her mother, and to the left his younger daughter Elizabeth, whom he also bastardized when he had her mother beheaded.

But this is more than a family portrait. It also symbolizes the political settlement by which Henry hoped to preserve and prolong his legacy.

To secure the Tudor succession, he decided that all three of his children would be named as his heirs. His son Edward would, of course, succeed him. But if Edward died childless, the throne would pass to his elder daughter, Mary. If she had no heir then her half-sister Elizabeth would become queen. The arrangement was embodied both in the king’s own will and in an Act of Parliament.

Henry’s provisions for the succession held, and, through the rule of a minor and two women, gave England a sort of stability. But they also ushered in profound political turmoil as well, since – it turned out – each of Henry’s three children was determined to use the Royal Supremacy to impose a radically different form of religion on England.

First, there would be the zealous Protestantism of Edward; then the passionate Catholicism of Mary. Finally, it would be left to Elizabeth to try to reconcile the opposing forces unleashed by her siblings.

The divisions within Henry’s family reflected the religious confusion in the country as a whole. The Reformation of the Church had been radical at times, cautiously conservative at others. In some parts of the country, people had embraced Protestantism and stripped their local churches of icons and Catholic ceremonies. In others, the people cleaved to the old ways, afraid of the radical change that had been unleashed. Like the royal family, Henry’s subjects were divided among themselves, unsure of the full implications of the Supremacy.

Containing this combustible situation was Henry VIII, with all his indomitable personality. On Christmas Eve 1545, Henry made his last speech to Parliament. It was an emotional appeal for reconciliation between conservatives who hankered after a return to Rome and radical Protestants who wished to press on to a complete reform of the Church. Henry sought a middle way which would both preserve the Royal Supremacy and prevent their quarrel from tearing England apart. It was also an expression of his personal views: he held on to the old ceremonies of the religion he had known from his youth; at the same time, he had repudiated the papacy that was their bedrock. And, as he was determined that his people should continue to tread the same narrow path, he made no secret of his contempt for the extremes in the religious disputes. Both were unyielding and zealous. Both were in some way flouting royal spiritual authority. Radicals and conservatives alike were under notice that unseemly disputes in the religious life of the country would not be tolerated.