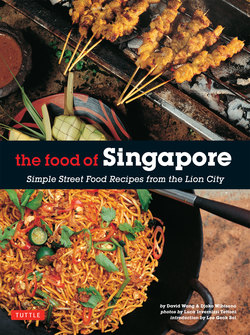

Читать книгу Food of Singapore - David Wong - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеMalay and Indian Food

On the food trail from Malaysia to Indonesia and the Indian Subcontinent

Both Indian and Malay cuisines are favourites for multi-racial gatherings in Singapore, especially since local Indian and Malay dishes are always halal (conforming to Muslim dietary laws). The Mughal Emperors and their court were Muslim, and it has become traditional in India and Indian restaurants the world over not to serve pork, which is prohibited by the Muslims, as well as beef, because of religious strictures imposed by Hinduism, which venerates the cow.

Malay food

Fragrant roots such as galangal (lengkuas), ginger and fresh turmeric, together with shallots, garlic, fresh and dried chillies, with emphatic overtones from lemongrass (serai) and belachan are what distinguish Malay curries from Indian ones Malay cuisine is the link between Indonesia, to the west and south, and Thailand to the north Although the results are rather different, there is a certain amount of overlap, especially with the food of nearby Sumatra and. In northern Malaysia, with Thailand fresh roots and seasonings typical of Malay food are used with spices like coriander, cumin and fennel, although these combinations are common in Indian curries. Coconut milk, widely used throughout tropical Asia, is added liberally to enrich many Malay dishes. Malay food also tends to be slightly sweet with palm or white sugar being a common ingredient, while tamarind juice gives a subtle tangy taste.

Although Malay food is not as prominent in Singapore as Chinese food, it is nonetheless part of the mainstream diet even for Chinese Singaporeans. Familiar favourites are the Malay classics such as Korma, Beef Rendang. Chicken Curry and the various sambals. An indispensible item in Malay cuisine, Sambal Belachan, has become so undeniably a part of the Singaporean diet, it appears as a standard condiment in most Chinese restaurants, complete with half a lime.

Nasi Lemak, a coconut-rich rice dish served with a variety of accompaniments such as crisp fried ikan bilis (dried baby anchovies), peanuts, prawn, shredded omelette and Chilli Sambal is what many Singaporeans eat for breakfast. Some of the kuih (cakes) associated with the Nonyas were Malay to start with, and, along with Chinese chui kuih (steamed rice cakes topped with Preserved Chinese Cabbage) and Indian roti prata, are consumed for breakfast and at teatime.

The highlight of Singapore's Malay cuisine is satay, thought by some to evolve from the Arab kebab but with a character ail its own. Satay has spawned two Chinese versions: satay chelop, known locally as lok lok—bite-sized pieces of meat, vegetables and various items speared onto satay sticks and cooked in a bubbling pot of peanut-based gravy—Nonya pork satay, and satay bee hoon.

On the other hand, roti john ("John's bread") was said to have been inspired by a homesick tourist named John who, so the story goes, was in search of a sandwich A helpful hawker sliced up a French loaf, clapped in a mixture of minced mutton and onion, dipped it in beaten egg, and fried it until crisp. Historically speaking, however, the dish—now a staple at Muslim food stalls—is more likely an adaptation of the Indian Muslim dish. Murtabak (stuffed fried pancake).

Indian food

The Indians, who form just over 7 percent of Singapore's population, are predominantly from the south of the subcontinent (mostly Tamils from Tamil Nadu, and some Malayalees from Kerala in the southwest). Like the Chinese, the Southerners arrived first and came in larger numbers compared to the Sindhis, Gujeratis, Bengalis, Punjabis and other Northerners who came later. Naturally, South Indian cuisine is more established and more common than that of the north.

Even non-Indians can easily tell the more fiery southern food from the milder Northern dishes. Indian cooking calls for spices such coriander, cardamom, cumin, fennel and cloves, but north and south use them differently. North Indian food is enriched with yogurt or cream, with a blend of chopped herbs, fresh chillies, and tomatoes added late in the cooking for a subtle flavour. These thicker curries are eaten with a variety of breads from unleavened flat chapati to puffy tandoor-baked naan Singapore's North Indians, like North Indians elsewhere, have a largely wheat-based diet, although they eat at least one meal of rice daily.

Festivals, such as the Muslim Hari Raya, at the end of the lasting month of Ramadan, provide an opportunity for (easting as well as for family reunions Visitors of all races are welcome during the traditional "open house".

South Indians, on the other hand, eat a rice-based diet that suits their more liquid curries, which are often enriched with coconut milk. However, the Southerners have their breads too: fluffy and ghee-rich roti prata. and dosai. tangy pancakes made from a fermented rice and dhal batter. Dosai do nicely for breakfast, lunch, tea and dinner, especially when they come in a variety of forms: crisp and paper-thin, fat and fluffy, plain or with curry filling.

The extensive use of dried beans and lentils in a variety of ways from staples to snacks gives Indian food a clout with vegetarians. Dosai shops are also often vegetarian restaurants since vegetarianism is mandated by Hinduism.

Named after the "plate" on which the food is served, "banana leaf restaurants" reduce the dishwashing load by having customers eat off banana leaves. Rice is surrounded by your choice of vegetables and dhal curries, crisp pappadam, cooling yogurt and tangy rasam (pepper water). Some banana leaf restaurants cater to carnivores, offering meat and seafood curries, the most popular being the local Fish Head Curry, which originated in Singapore.

While Singapore Indian food has most of the characteristics of Indian food elsewhere, it has not escaped the influences of the other ethnic communities. Apart from Fish Head Curry, another local Indian favourite is Indian Mee Goreng, fried yellow noodles prepared with chillies, potato, bean sprouts, tomato ketchup and some curry spices. There is also Indian Rojak, which has rather non-Indian ingredients, such as Javanese tempeh, Chinese fried tauhu and fishcake along with boiled potatoes, hard-boiled eggs in batter and a choice of fritters, all eaten dipped in a sweet potato sauce, served with green chilies and slices of onion and cucumber.

Sup Kambing (mutton soup) is another Indian dish with a Chinese accent: lots of fresh coriander leaves (cilantro) to perk up the robust soup seasoned with spices The soup comes invariably with crusty roti perancis (French bread). South Indian food is often prepared by Indian Muslims, some of whose restaurants along North Bridge Road are well-known for their Murtabak and biryani. a fragrant saffron-coloured rice flavoured with fried onions, spices, raisins and nuts, cooked with mutton or chicken.

Indian Rojak, a distinctive Singapore Indian version of a Malay Indonesian snack, is a dish you'd never find in India.

So-called "banana leaf restaurants' offer a selection of food served on the original disposable plate Typical dishes include the famous Singapore Indian dish. Fish Head Curry, as well as succulent crabs and spicy prawns.