Читать книгу Power Play - Deaglán de Bréadún - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

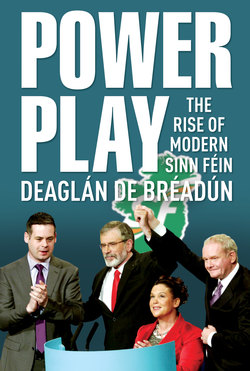

Оглавление2. HELLO MARY LOU – GOODBYE GERRY?

SHE IS OFTEN SPOKEN of as the future leader of Sinn Féin. And if or more likely when – the party enters a coalition government in Dublin, it is inconceivable that she would not be a cabinet minister. Mary Lou McDonald is rarely out of the news, and this chapter explores the background to her political career and the journey she has made from Rathgar and Fianna Fáil to Leinster House and Sinn Féin.

With the general election drawing close at the time of writing, McDonald is a high-profile player in Republic of Ireland politics. If the dice fell the right way and Sinn Féin could lay claim to the job of tánaiste (deputy prime minister) or even – heaven forbid, their critics say – taoiseach(prime minister), it is not entirely fanciful to suggest that she could be in the running. This is partly due to her own abilities and performance as deputy leader of the party, but it is also down to the fact that Gerry Adams is such a highly-controversial figure. The scenario prior to the formation of the first inter-party government in 1948 has been evoked in this context.1 On that occasion, the leader of the biggest party in the preliminary negotiations was totally unacceptable to others at the table. Richard Mulcahy was head of Fine Gael, but his role in the ruthless Civil War executions of anti-Treaty republicans ruled him out as taoiseach. The main opponents of such a move were Clann na Poblachta (Family/Children of the Republic). Many of its activists were former IRA members, and party leader Seán MacBride had been IRA chief of staff in the 1930s. The issue was resolved when Fine Gael proposed John A. Costello, a prominent Dublin barrister and professional colleague of MacBride’s, to head up the new government, although Mulcahy retained the title of party leader. There is, of course, a considerable difference between the political outlook held by Richard Mulcahy and the worldview of Gerry Adams. Yet the theory goes that, just as the Fine Gael leader had to take a step back, so would Adams need to temper any ambitions he might have. Mulcahy got the job of Minister for Education as a consolation prize in 1948 and some have suggested that, given his interest in the Irish language, the portfolio of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht might be suitable for Adams. It is, of course, a highly-speculative scenario. Alternatively, Adams might emulate MacBride by taking over Foreign Affairs, a post in which he would revel, though it would cause flutterings and maybe panic attacks in some of the chancelleries of Europe.

Sinn Féin is admittedly very loyal to Adams, and would have great difficulty in accepting that he was somehow ineligible for the office of taoiseach or tánaiste. Who knows, though, what might happen in what were called the ‘smoke-filled rooms’ – before the tobacco-in the-workplace ban, that is. Of course, there is no guarantee at time of writing that the party will be ‘in the mix’ when the next government, or indeed its successor, is being formed. Quite apart from government positions, there has been endless speculation about McDonald as the most likely contender to take over from Adams as Sinn Féin leader. It is virtually de rigueur for any media profile of the deputy leader to dwell at some length on the prospect of her taking the top job in the party.

The ‘Backroom’ column in the Sunday Business Post put it in the following colourful terms: ‘Just as Micheál Martin is a human reminder to potential Fianna Fáil voters of the [Brian]Cowen years, so too Gerry Adams is a human reminder to potential Sinn Féin voters of the dark days of the IRA. Maybe it’s time the party thought of replacing the ‘Big Bad Wolf ’ at its head with Mary Lou. It could make the difference between Sinn Féin getting into the next government and, dare we say it, leading the next government [emphasis added].’2 At any large Sinn Féin gathering, the 2015 ardfheis in Derry or the Easter Rising commemorative parade in Dublin in April 2015, for example, it is very obvious that, while the party has drawn an impressive level of support from young working-class males, it badly needs to broaden its appeal. McDonald’s presence in the leadership – despite one observer noting that ‘her south county lilt is overlaid with a hint of a Dub drawl – is made into a greater asset by virtue of her being a woman from a middle-class background.3

Journalist Harry McGee has written that, given the symbolism of the 1916 Centenary, Adams will undoubtedly lead Sinn Féin into the next election, which is due to take place by April 2016 at the latest. Assessing Mary Lou’s prospects after that, McGee wrote: ‘There are few politicians who impress TDs from rival parties more than McDonald. She is a great communicator, authoritative and focused, though at times too obdurate. She can sometimes be caught out on detail. McDonald is deputy leader, a woman, who is also well-got with the party’s key leaders in Northern Ireland. That makes her the front-runner.’4

When asked, in an interview for this book, if she saw herself going for the leadership within the next five years, McDonald replied: ‘I wouldn’t put a precise time-frame on any of this, but I have said externally and internally that, as and when the vacancy arises, I am interested. I mean, unless I radically change my mind in the intervening period’. She went on to stress, however, that she had no wish to see Adams stepping down:

No, I am not in any hurry. I think Gerry has proven his worth again and again and again and, despite what his detractors say, the facts are that the party has been built, our support has been built, strongly, north and south, under his stewardship. He would be the first to tell you that he didn’t do it on his own; it is a collective leadership. You have Martin McGuinness in the mix, you know, a whole range of different characters.

When asked if she would be putting Adams under any pressure to go, she replied: ‘Oh God no, absolutely not.’5 Her answer was similar to the one she gave Alex Kane in the Belfast Telegraph, when he asked her if she wanted the job: ‘Not in the short term, but I wouldn’t rule it out in the longer term. It’s not something I’m concerned with now, but at some stage, if there were a vacancy, I would certainly consider it.’6

Other names mentioned for the leadership include: Donegal TD Pearse Doherty, who is the party’s finance spokesman; former MP for Newry and Armagh and one-time republican prisoner, Conor Murphy; and the North’s Education Minister, John O’Dowd. However, observers believe that McDonald is the chosen one, and that the succession will take place at a time that is deemed appropriate. In or out of government, and whether or not she succeeds Adams as Sinn Féin leader, there is little doubt that McDonald will continue to be a significant figure in Irish politics for years to come.

So who is she, and what is her background? How did someone considered to have been born with the metaphorical silver spoon in her mouth and a well-lit pathway into the professional classes end up as deputy leader to a band of self-proclaimed revolutionaries? Born on May Day 1969 in Dublin’s Holles Street hospital, McDonald grew up in the leafy suburb of Rathgar. The family home was at Eaton Brae, a quiet enclave off Orwell Road, and close to the impressive property that houses the Russian – formerly Soviet – Embassy. A family friend says that, despite the location, her circumstances were by no means luxurious.

In an interview for a very interesting book in 2008, about politicians whose first name is Mary, she told former MEP for Fine Gael Mary Banotti that she was originally meant to be called Avril, as she was due to arrive in April. Though christened Mary Louise, this was quickly shortened to Mary Lou: ‘When I was a child I would very rarely be called Mary Louise unless I got into trouble. When the voice was raised and I got my full title I knew that I had crossed some line.’7 The classic Ricky Nelson pop-song Hello Mary Lou (Goodbye Heart) became one of her pet hates, though her canvassers in the Dáil constituency of Dublin Central consider it an asset. She herself wrote after the 2011 general election: ‘The song filled the Cabra air and echoed throughout the north inner city. A group of women jived to it on Sheriff Street, proof-positive according to one activist that the song was a vote-getter. I sincerely doubt it.’8

Most profiles of Mary Lou describe her father Patrick McDonald as a surveyor, but when interviewed for this book, she pointed out that ‘building contractor’ was the correct description. Like so many people from the building trade, he joined Fianna Fáil. Her mother, Joan, was also a member of that party ‘for a short while’, she recalls: ‘When we were growing up, she’d be the kind of person who’d be writing letters to prisoners of conscience. She’d be into Amnesty International and she was very involved in the Burma Action Group. As much as she would have a view on domestic politics, my mother would always have had a broader political sense of things.’ The biggest role in shaping the young Mary Lou’s outlook, however, was apparently played by her maternal grandmother, Molly, whom she describes in the Banotti interview as ‘very political in her thinking, very nationalist, very old-style republican.’ Interviewed for the present book, McDonald said: ‘She died some years ago and I miss her. She was a big influence on me.’9

Despite the dreams and desires of socialists and Marxists over many generations, the historic dividing-line in the politics of the Republic of Ireland was not class, but what side your forebears had taken in the Civil War. That awful conflict erupted over the terms of the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921, and ultimately gave birth to Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, as well as hardening the stance of Sinn Féin on the militant fringe.A brother of Molly’s (and grand-uncle to Mary Lou), James O’Connor from Bansha, County Tipperary, took part in the War of Independence and later sided with those who opposed the Treaty and the Irish Free State that arose out of it. On 13 December 1922, as civil war raged, the young railway worker was one of a group of anti-Treaty IRA activists arrested in County Kildare, close to the Free State army camp at the Curragh. The episode is recalled in a book on how the war was fought in County Kildare. In a fascinating chapter poetically entitled, ‘Seven of Mine, said Ireland’, author James Durney tells us that two months before their arrest the Rathbride Column, as they were called, had sent a runaway engine down the main Kildare line.10

The Irish Times, on 23 December 1922, quoting an unofficial briefing by the Free State authorities, reported that the IRA members had attempted to dislocate the Great Southern and Western Railway line using two spare engines to set up an obstruction at Cherryville. This was a major security threat because, as Durney points out: ‘The Cherryville junction was vitally important as it had railway links to west and south.’ The unit was also said to have ambushed Free State troops at the Curragh Siding, on 25 November. There were accusations as well that looting was carried out on shops and other business premises in the locality, although these claims were strongly rejected by surviving relatives and supporters.

Whether as a result of surveillance or inside information, the anti-Treaty unit was traced to a dugout or tunnel underneath the stables of a farmhouse at Moore’s Bridge, about 2.5 kilometres (1.5 miles) from the Curragh camp. The intelligence officer of the group, thirty-one-year-old Thomas Behan was shot dead, during or after his arrest. While it is alleged that he was shot out of hand, the official record states that he was trying to escape from his place of detention.

Having been found guilty by a military court of possessing arms and ammunition, seven members of the group were executed on the morning of 19 December 1922. Three of them were aged between eighteen and nineteen years. Each of them was shot by firing squad, one after the other. They are said to have shaken hands with their executioners, and to have sung The Soldiers’ Song, which has a chorus that begins: ‘Soldiers are we, whose lives are pledged to Ireland.’ This was a clarion-call of the Volunteers in the General Post Office at Easter 1916, and later, in the Irish-language version Amhrán na bhFiann, became Ireland’s national anthem.

Two members of the column were spared: Pat Moore (whose brother, Bryan, was shot as commanding officer of the unit) and Jimmy White (whose brother, Stephen, was executed with the other six). Durney comments that ‘it was probably a step too far to execute two sets of brothers at the one time’. The column had been arrested at the family farmhouse of Bryan Moore and his sister, Annie, who was also taken into custody. Annie’s fiancé, Patrick Nolan, was among those executed. In a state of inconsolable grief, she was taken to the female wing of Mountjoy jail in Dublin. In a last letter to his parents, Nolan wrote: ‘Dearest Mother, there are a few pounds in my suitcase, you can have them, or anything else in the house belonging to me.’ James O’Connor wrote to his mother: ‘I am going to Eternal Glory tomorrow morning with six other true-hearted Irishmen’. It was the largest group to be executed during the Civil War, in which there were seventy-seven official executions. The seven are known as the Grey Abbey Martyrs, and their deaths are still commemorated by republicans today.

Mary Lou has rural connections, with her mother – O’Connor’s niece – coming from the Glen of Aherlow, and the family retains strong Tipperary links. These connections are important in Ireland; her father was born in Dublin, but with roots in County Mayo.11 Mary Lou’s parents separated when she was only nine years old. Such occurrences were relatively rare in the Ireland of that time, a state where divorce was banned until 1995. In the Banotti interview, she said: ‘That was a big disruption in our family life but it was something we got through.’ The children remained with their mother. All of them did well in their careers. Mary Lou told me: ‘We worked hard, that is the ethos of our house. If you wanted to get ahead, you got cracking and there was an expectation that you’d do well at school and work hard. We were just, I suppose, lucky as well.’12 There were four children in the family, two boys and two girls: ‘I’ve an older brother called Bernard, then there’s myself and the set of twins, Patrick and Joanne.’13 A scientist by profession, Joanne hasbeen associated with Éirigí [Rise Up!], a left-republican group that is critical of the Good Friday Agreement and seeks to build a mass radical movement but does not advocate a renewed campaign of violence. Mary Lou says they get on very well: ‘I only have one sister. I love my sister and we’re on great terms. She’s got two lovely children, I’ve got two children. We’re very close, we’re a very, very close family.’14 Mary Lou had just turned twelve when IRA prisoner of the British and abstentionist MP for Fermanagh-South Tyrone, Bobby Sands, died on hunger strike. She was later quoted as saying that this was a ‘road to Damascus’ moment.15 She clearly recalls the ‘sheer brutality’ of the ten hunger strikers being allowed to die: ‘And that was beamed into your front room.’16 She attended a Catholic girls school on nearby Churchtown Road: Notre Dame des Missions, founded in 1953 by the order of nuns which bears that name. In a table of private schools, published in the Irish Independent on 17 September 2014, Notre Dame was listed as charging €4,300 per annum, with day-fees at other private schools in the Dublin area generally ranging from €3,600 to €12,000-plus.17 The points she got in her Leaving Certificate at Notre Dame were insufficient for her purposes, so she repeated the exam the following year at Rathmines Senior College. She then started a four-year course in English Literature at Trinity College Dublin (TCD), no longer seen as a unionist enclave since the Catholic Church lifted its ban in 1970 on members attending the college.18 In tandem with her social background, McDonald’s schooling contributed to the self-confidence that is one of her hallmarks as a politician. As she told Banotti: ‘I had a great education and a great sense of myself.’19 She has warm memories of her teachers at Trinity, among them being the eloquent and feisty Independent Senator David Norris. ‘It wasn’t so much that he taught – he performed! And it was absolutely brilliant,’ she told me. The prominent Kerry-born poet and academic Brendan Kennelly also gets full marks from Deputy McDonald: ‘Brilliant in tutorials, a really good teacher, very affable and very connected with the students.’20 Despite the impact the hunger strikes had on her when she was younger and her parents’ interest in political issues, she kept aloof from such involvement at TCD. This seems strange in light of her later activity, since for many people it is their only period of activism. How was she able to keep clear of the political arena? ‘Well, actually, with relative ease, because I liked my books, I liked my friends and I always worked when I was in college. So I always kept myself very well out of it.’21 Her mind was on the glories of literature in the Saxon tongue: ‘I liked all the Anglo-Irish [writers]. I particularly liked Beckett’s theatre. I know it’s very dark: I got a kick out of that. I liked the Metaphysical Poets and American literature. I went through a phase of Sylvia Plath; I think every college student does.’22 She had a break abroad before the end of the four-year degree course: ‘I took a year out when I was studying in Trinity and I went to live in Almeria, in Andalucia, in the south of Spain. It was after third year: a gap year. I taught there – the typical kind of thing.’ She still heads off to Spain for a holiday when she gets a chance. After the Easter break in 2012, Labour’s Pat Rabbitte responded to her latest criticism of the Government in the Dáil with the memorable quip: ‘Such tanned indignation!’23

After graduation from Trinity she spent a year at the University of Limerick (UL), where she took a Master’s degree: ‘That was in European Integration Studies: law, economics, politics. I think I was the only person in the class that didn’t have a degree in Economics or European Studies.’24 When asked what motivated the shift from English Literature to European Studies, she says she had an interest in the European Union and its institutions: ‘I go on instinct on lots of things. I didn’t have a masterplan where I carefully plotted-out every step of a career-path... That’s self-evident!’25 After UL, she worked as a researcher in a Dublin-based think tank, the Institute of International and European Affairs. The IIEA was founded in 1990 by former general secretary of the Labour Party, Brendan Halligan.‘I went on to Dublin City University (DCU) where I started my PhD. It was in Industrial Relations/Human Resource Management.’ This was meant to be a follow-up to her MA thesis at UL which was concerned with the 1993 re-organisation of the state airline, Aer Lingus. ‘I was in the IIEA, went into DCU, was working away, did some teaching, working away on my research, and then I went to the Irish Productivity Centre, to work as a consultant.’26 Romance enters the story too: during the heady days of 1990, when the nation was buoyed with hope because of the Irish soccer team’s performance in the World Cup, Mary Lou met her future husband, Martin Lanigan, in Peter’s Pub in downtown Dublin. They married in 1996 in a Catholic wedding at University Church, and they had their reception in the historic Tailors’ Hall, which featured in the events leading to the 1798 rebellion. Martin works in the emergency section of a utility company. They have two children, Iseult, born in 2003, and Gearóid, named after her husband’s father, who arrived in 2006.

Mary Lou’s first involvement in politics came in the mid-1990s when she joined the Irish National Congress (INC), a campaign group which promotes the aims and ideals of Irish republicanism on a non-party basis. The INC was originally set up in 1989, under the chairmanship of leading artist Robert Ballagh, to prepare for the 75th anniversary of the 1916 Rising two years later. In the anti-republican, revisionist climate of the time, official celebrations were going to be quite modest and far different in scale from what would later be planned for the centenary in 2016.

McDonald and Finian McGrath, who was subsequently elected to the Dáil as an Independent, both served in the position of leas -chathaoirleach (vice-chair) of the organisation in the mid-90s. McDonald chaired the organisation for a year from March 2000.27 McGrath told me:

The idea was, we were trying to do a copy of the ANC [African National Congress] in South Africa, because Mandela was on the way into power at the time and we just had this idea of having a broad republican nationalist front that would include every [individual or organisation]– including Sinn Féin, including independents like myself – that had a national vision for the country.

McGrath says that they worked closely as joint vice-chairs of the INC: ‘She was a fantastic speaker, a woman of great belief. She had a great vision for our country at the time and was also very proactive in developing and supporting the early stages of the peace process, when a lot of people were hostile to it.’28 The INC newsletter of April 2000 which announced her appointment as chair by the national executive also declared the organisation’s intention to hold ‘an anti-sectarian protest’ in Dublin on 28 May.29 This was in opposition to a proposed march by the Dublin and Wicklow lodge of the Orange Order and the unveiling of a plaque at 59 Dawson Street, in the city centre, where the first meeting of the Grand Orange Lodge of Ireland was held on 9 April 1798.

The Order sees itself as an unapologetic defender of Protestant civil and religious liberties, but its critics, with equal forthrightness, claim that its activities are damaging to community relations.There were major tensions and disturbances in Northern Ireland on an annual basis over a proposed Orange Order march through a nationalist area on the Garvaghy Road in Portadown. The INC was very involved in this issue, and McDonald herself visited the scene. The parade in Dublin was called-off and the counter-demonstrators were accused of intimidation. In a letter published in the Irish Times on 10 May, McDonald rejected this allegation and the notion that the Order had been ‘demonised’ by herself and other critics.

On 28 May, Dublin’s Lord Mayor, Councillor Mary Freehill of the Labour Party, unveiled the Dawson Street plaque. No one from the Orange Order was present but the Irish Times reported that the crowd of about 150 included a ‘bevy’ of protesters from the INC: ‘These carried placards with messages such as “Dublin says No to sectarianism”, as well as a mock Orange banner comparing the Order to the Ku Klux Klan. A spokeswoman, Ms Mary Lou McDonald, said the Congress was not opposed to the unveiling of the plaque. The protesters were there to register their “strenuous objections” to the way the Lord Mayor had engaged with the Orange Order. She accused Cllr Freehill of failing to recognise the scale of the sectarian problem in Ireland and of ‘ingratiating’ herself with an organisation “which continues to foster division and fear”.30 The Lord Mayor was quoted as saying that, ‘the Order represents a significant strand in the politics and culture of those claiming a British-Irish identity. It is part of our shared history and should be recognised as such’.

In a letter published on 27 June in the Irish Times, McDonald said one of the reasons for the INC demonstration was ‘to remind elected representatives of their responsibility to defend the right of Irish citizens to live free from sectarian harassment, as expressed in the Good Friday Agreement’. Responding in the letters page on 3 July, Julitta Clancy of the Meath Peace Group said she was ‘delighted to learn that the INC now seems to be accepting the Agreement which it strongly opposed in 1998’. Replying, McDonald said that, ‘contrary to Ms Clancy’s assertion, the Irish National Congress did not oppose the Good Friday Agreement’. She reiterated in an interview for this book that the INC did not oppose the Agreement, although there were ‘mixed views’ about it among the membership. ‘The Articles 2 and 3 issue was very, very “angsty” for the Irish National Congress,’ she said, adding that she did not share those concerns. ‘At the time that issue of Articles 2 and 3 was huge for nationalist Ireland, I suppose most markedly for people in the South.’

Separate referendums were held on the two sides of the border in the aftermath of the successful conclusion of multi-party talks at Stormont’s Castle Buildings on Good Friday, 10 April 1998. The electorate in the Republic were asked to vote on a new version of Articles 2 and 3 which accepted that the North could not become part of a united Ireland without the consent of a majority in each jurisdiction. A front-page report in the Sunday Business Post on 15 March 1998 said the Irish Government was proposing to change Articles 2 and 3 without any meaningful quid pro quo from the British, and that ‘the Irish National Congress is to launch a petition next week among the North’s 675,000 nationalists to protest at the Government’s planned action which the INC holds is a devastating destruction of the definition of the nation’. No such petition was launched in the end and plans for an intensive INC campaign to defend Articles 2 and 3 evaporated when Sinn Féin assented to the Good Friday pact. The organisation’s newsletter for January 1999 states that the INC adopted ‘a critical but not hostile approach’ to the Agreement and subsequent referendums.

While it may be technically correct to say that the INC, as an organisation, did not oppose the Good Friday/Belfast Agreement outright, it was clearly very unenthusiastic about elements of the deal, especially – but not exclusively – the changes in Articles 2 and 3. The newsletter states: ‘During the referenda campaign on the Belfast Agreement and constitutional changes, the INC launched a media campaign criticising the proposed wording as well as the indecent haste and lack of debate surrounding the amendments. To counteract the unanimously one-sided media coverage the INC also produced a Critique of the Belfast Agreement pointing out some of its shortcomings.’ The INC chair from 1989 to 1998, Robert Ballagh, declared his intention to vote No in the referendum held in the Republic. This was because the Irish territorial claim was being removed but the British one still remained. Secondly, he believed the Agreement was ‘flawed’ and did not guarantee peace.31

Initially, Gerry Adams indicated that Sinn Féin might well vote for the Agreement in the North and against it in the southern referendum, because of the proposed changes in Articles 2 and 3.Sinn Féin TD for Cavan-Monaghan, Caoimghín Ó Caoláin initially also expressed opposition to ‘any dilution or diminution of Articles 2 and 3’. But in the end, 331 out of the 350 Sinn Féin delegates at a special conference in Dublin on 10 May 1998 voted to accept the Agreement and, by implication, to vote Yes in both referendums.

McDonald told this writer that she was persuaded to join the INC by a Fianna Fáil activist, Nora Comiskey, a son of whom was a lifelong friend of Mary Lou’s husband. Nora Comiskey also persuaded her to join Fianna Fáil. Asked why she chose that party, she told me: ‘Probably a mixture of things, my family in the main, although it is not true to say all of them would have been Fianna Fáil. You know how this shakes down in terms of families that fell on one or other side of the Civil War politics. And then I had a very close friend who remains a close friend of mine, who is a lifelong Fianna Fáiler and a lifelong republican, Nora Comiskey’. McDonald joined a cumann (branch) of the party in the Dublin West constituency which encompassed Castleknock, where she lived at the time. Several long-time members from different wings of Fianna Fáil have insisted to me that she was ‘shafted’ by supporters of local TD and future, highly-respected finance minister Brian Lenihan Jr, who later died of cancer at the age of fifty-two. She equally-strongly rejects this version of events: ‘That’s not true. I don’t think that’s fair. I read these accounts that, “She left because she didn’t get a nomination for a seat”. I tell you – no such thing, and in no shape, manner or form was I shafted by the Lenihans or by anybody else.’ A long-time Fianna Fáil activist told me that ‘Lenihan ran her out of it’, and that this was bitterly resented in the McDonald camp. But Mary Lou is categoricaly insistent that, far from having her ambitions frustrated and blocked by the local party establishment, she felt instead that there was a lack of a serious social policy dimension in Fianna Fáil’s version of republicanism:

What happened was this. I arrived in: they were lovely people, Nora in particular. Everything was going along, happy days. I went to one meeting, I went to another meeting. There was a discussion, and I raised the idea of – I don’t think I even used the word ‘equality’, I think I used the word ‘equity’– and there was a kind of a puzzled intake of breath in the room.32

She addressed the party’s ardfheis, which was held at the Royal Dublin Society premises in November 1998. The issue was policing in Northern Ireland, and the Irish Times reported:

Ms Mary Lou McDonald, Dublin West, speaking on the reform of the RUC [Royal Ulster Constabulary, predecessor of the current Police Service of Northern Ireland], said the RUC was composed exclusively of people from one tradition and they were utterly incapable of carrying out fair policing. There had been victims who had died at the hands of the RUC. There needed to be root-and-branch change to the policing system.33

McDonald had the feeling that her interest in the North, especially the Orange Order dispute with nationalist residents in Portadown over its demand to march along the Garvaghy Road, was not widely shared in the party. This contributed to her decision to leave Fianna Fáil after about a year:

I had been active then on the parading issue in Garvaghy Road and all of that, and there was kind of a very mixed response to that within the party, and a level of disengagement. So it all amounted to me saying, you know, this is just the wrong place for me. It wasn’t to cast an aspersion on anybody else: it was the wrong place for me to be. That was the sense, so I was sort of a misfit in that whole scenario.34

Along with suggestions that her progress was obstructed in Fianna Fáil, there is an apparently contradictory claim that she turned down a nomination to run for a ‘safe’ council seat in the June 1999 local elections. She flatly denies this also: ‘Listen, I was neither shafted nor was I offered a seat. It didn’t arise.’ Asked how her move to Sinn Féin came about in the end, she says:

I suppose, first of all I knew some of the lads through the Irish National Congress, although that wasn’t the crucial thing... I remember going to a meeting in the Mansion House. Gerry [Adams] spoke at it, I can’t remember if Martin [McGuinness] spoke at it, I don’t think he did. But certainly Gerry spoke at it, and I just said to myself: ‘These people actually have their act together. And they know what they are doing’... Maybe it was a bit of a leap of faith on my part because I would have known certain individuals within Sinn Féin, but I wouldn’t have grown up in a place where Sinn Féin was organised and kind of a known quantity and all of that stuff... But it was just the politics of it sort of appealed to me: that blend of support for the peace process, Irish unity, all of that matters a great deal to me. But then, joined, inextricably bound up with that: social justice and social equality... For my politics, I wanted both of those things, I didn’t want a little bit of one or a little bit of the other, I wanted both of those things, so that’s where the Sinn Féin appeal was for me, and it was the right decision... The party was smaller at that stage, it was a more closed circle in a sense. So you arrived along as a kind of a new person in it; right enough, people take the measure of you and suss you out, which is all fair enough, but notwithstanding all of that I think I knew pretty quickly that I was in the right spot.

She believes the party is more open to new recruits nowadays: ‘I think for people joining now, perhaps particularly women, they come into a very different atmosphere and a very different environment.’ (There was a time when joining Sinn Féin might have led to some Garda surveillance because the IRA campaign was in full swing but McDonald says she did not experience any of that.)35

She told Alex Kane in 2013: ‘When I got politically involved, when I became active, I was looking for somewhere you could actually make a difference, and Sinn Féin provide that space. There’s a kind of stereotypical thing about what a ‘Shinner’ should look like and that doesn’t tally with the reality.’ Kane commented: ‘She was a perfect catch for Sinn Féin, exactly the sort of person they needed: the sort of person who would normally have pursued a career in Fianna Fáil. She was young, bright, articulate and attractive.’3636 A general election was called in the Republic in 2002, and McDonald was chosen as the Sinn Féin candidate in Dublin West. This was her first time to run for public office and she secured 2,404 votes, equivalent to 8.02 per cent of first preferences. Coming seventh in a field of nine, she was eliminated on the third count. Brian Lenihan Jr topped the poll for Fianna Fáil, with Trotskyist candidate Joe Higgins of the Socialist Party (who got almost half of Mary Lou’s transfers under the Irish system of proportional representation), and Labour’s Joan Burton, taking the other two seats.37

Her internal rise in Sinn Féin has been a rapid one. In 2001, she became a member of the ardchomhairle (executive council); four years later she succeeded Mitchel McLaughlin – currently the speaker of the Northern Ireland Assembly – as chair of the party. And in 2009 she took over from Pat Doherty – currently abstentionist MP for West Tyrone – as vice-president. McDonald attracted controversy when she took part in a commemoration ceremony at the statue of former IRA leader Seán Russell in Dublin’s Fairview Park on 17 August 2003. A photograph in the Sinn Féin newspaper An Phoblacht for 21 August 2003 shows McDonald, at this stage a declared candidate in the following June’s elections to the European Parliament, smiling benignly at Belfast republican Brian Keenan, who gave the main oration.

Born in Fairview, Russell took part in the 1916 Rising and sided with the anti-Treaty IRA through the Civil War and beyond. In 1926, he was part of a mission to buy arms in the Soviet Union. In 1938 he was appointed chief of staff of the IRA. Regarding itself as the true government of Ireland, the organisation declared war on Britain in January 1939 and began a campaign of bomb attacks on British targets, especially electricity supply-points. An apolitical militarist, Russell did not care who provided arms to the republican movement and took very literally republican father-figureWolfe Tone’s dictum that ‘England’s difficulty is Ireland’s opportunity’. He travelled to the US to drum up support, got arrested, skipped bail, secured passage on a steamer heading for Italy and, in May 1940, ended up in Berlin. After three months’ training in explosives, he headed back to Ireland on a German U-boat in the company of Spanish Civil War veteran Frank Ryan, who had just been released from one of Franco’s prisons into German hands. However, Russell became ill and died at sea on 14 August 1940, with the result that the mission was aborted. Reporting on Keenan’s speech in Fairview, An Phoblacht said:

Brian reviewed the strange history of Seán Russell from his birth in Fairview in 1893 to his death at the end [sic] of the Second World War. He talked about the part Russell had played during the ‘20s and the ‘30s in the ideological disputes surrounding the RepublicanCongress and the formation of Saor Éire, and his role, as IRA Chief of Staff, in the disastrous campaign in England during the Second World War […] ‘I don’t know,’ Brian acknowledged, ‘what was in the depth of Seán Russell’s thinking down the years, but I am sure he was never far from Pearse’s own position, who said, ‘as a patriot, preferring death to slavery, I know no other way’.38

Keenan, who died of cancer five years later, was himself the mastermind of an IRA bombing campaign that unsettled London in the mid-1970s. He was jailed for eighteen years in 1980 for his involvement in the deaths of eight people, including author and broadcaster Ross McWhirter, who had offered a £50,000 reward for information leading to the arrest of IRA bombers, and oncologist Gordon Hamilton-Fairley, one of several people killed by car bombs.39 Earlier, Keenan had travelled extensively to establish contacts in East Germany, Lebanon and Syria, and negotiate arms deals for the IRA, most notably with Libya’s Colonel Gaddafi in 1972. But following his release on parole in 1993, Keenan used his influence to persuade the IRA leadership to embrace the peace process. At his funeral, members of the Balcombe Street Siege group - the IRA unit that Keenan organised in England in the mid-1970s - carried his coffin.

Two weeks after the Fairview ceremony, columnist Kevin Myers castigated McDonald in the Irish Times for her participation in a ceremony to honour a ‘filthy wretch’, whose collaboration with the Nazis took place after Hitler had publicly pledged to exterminate the Jews of Europe. Noting that McDonald was a candidate in the European elections, Myers wondered what she would say to her parliamentary colleagues if ‘by some extraordinary freak’ she won the seat: ‘At the EU bar, would she break into a jolly rendition of Horst Wessel [the Nazi Party anthem], a beer tankard in her hand?’40 The issue surfaced again, inevitably, in the run-up to the European elections. The weekend before the 11 June polling day, Fianna Fáil candidate Eoin Ryan said Keenan was a senior IRA figure who had served a prison sentence in England for explosives offences. He added:

The people of Dublin and Ireland should know the kind of company Mary Lou McDonald keeps. And what of the person McDonald and Keenan gathered together to ‘pay respect’ to – Seán Russell, a self-proclaimed ally of Hitler, Nazi Germany and former leader of the IRA.

A Sinn Féin spokesman responded: ‘I think Eoin Ryan should look at his own party’s history before starting to throw around accusations... considering Eamon de Valera signed a book of condolences on the death of Adolf Hitler.’41 Myers returned to the subject twice more in his ‘Irishman’s Diary’ column, most notably on 1 February 2005, the year after the election, when he wrote: ‘Not merely has Mary Lou McDonald increased in size since her election to the European Parliament, but she is the only MEP who has publicly honoured a Nazi quisling... When Big Mac gave the keynote [sic] oration for Russell, she was truly speaking the language of Sinn Féin-IRA and its weird, demented ethos... Big Mac is just junk.’

McDonald told this writer she had no regrets over her participation in the Russell ceremony:

No, I mean, for God’s sake, if you could criticise anything, you would criticise factions within the IRA at different stages that had such a militarist view on things that they didn’t see broader politics.I don’t think for one minute that Russell was an arch-Nazi or a Nazi supporter. The facts actually, if viewed rationally don’t support that case, but that’s what Myers is trying to do. But at that time if I recall, Kevin Myers had taken a good number of side-swipes and hard runs at me. That is his prerogative but – pretty nasty stuff!

Asked if it hurt to be attacked in that way, she replied:

Not hurt I was more taken aback by it, because I suppose I hadn’t been through, like others, the school of hard knocks. Bear this in mind: one day I was going about minding my own business, then, when I ran in that European election in 2004, literally within a matter of months, anywhere you would go people knew your name and recognised you.That’s quite a transition for a person, in a very quick period of time. And then you get the criticism and you have to take it, but it throws you a little bit off balance. Nowadays, it wouldn’t have that effect on me at all, but that’s just experience and the value of growing older.

(The Russell statue was vandalised in December 2004 by an unnamed group who said in a statement he was a Nazi collaborator; it was later repaired.)

Regarding the response to her European candidacy, she told Banotti (a grand-niece of rebel leader and founder of the Free State, Michael Collins): ‘The only thing that irked me, as a woman, was the suggestion, sometimes said up-front and sometimes just implied, that I was maybe cute but not that bright. They were saying that this woman was being run because she was being groomed as the new face of Sinn Féin and she was respectable. And never a thought that maybe this is a capable person, someone who has the confidence of those she works with to go out and do this job. This irritated me, but I suppose it was par for the course.’

It would have been interesting to see the reaction of former neighbours in the leafy suburbs to her election campaign, but the party wasn’t having any of that. Alison O’Connor wrote in the Sunday Business Post: ‘A request to see McDonald, who grew up in the south Dublin suburb of Rathgar, canvassing in her heartland of middle-class Dublin was ignored. Instead, an initial offer came to accompany her on a canvass of an inner-city flats complex, and eventually an old local authority estate in Crumlin.’42

Journalist Michael O’Regan wrote with foresight, six months in advance of the June 2004 European contest: ‘Dublin could provide Sinn Féin with its first Euro MEP in Ms Mary Lou McDonald, who polled 2,404 first preference votes in Dublin West in the 2002 general election. The party has since grown in strength in the capital, with Ms McDonald’s profile increasing. Political observers notice that she was given a very high profile by the party during the Northern elections, posing for photographs and television cameras with the leader, Mr Gerry Adams.’43 It was an indication of the effort being put into the campaign and the reception it was getting that the pseudonymous Drapier column in the Irish Times reported hearing that a rally in the middle-class suburb of Dundrum in south Dublin on 30 March, where Adams and McDonald were speaking, drew ‘a huge overflow attendance with the crowd in the hall spilled outside’.44

Meanwhile, Sinn Féin’s apparent reluctance at the time to dispense with the legacy of the ‘Long War’ in the North was becoming a political weapon in the hands of the party’s opponents. Progressive Democrat TD for Dun Laoghaire, Fiona O’Malley highlighted the sale of paramilitary souvenirs in Sinn Féin shops. She said the sale of T-shirts bearing the logo ‘IRA – UndefeatedArmy’ and lapel pins with the slogan ‘Sniper at Work’ were helping to fund Sinn Féin election candidates. (This issue has been raised in more recent times by Fianna Fáil leader, Micheál Martin.)When asked at the time if she approved of the ‘Sniper at Work’ badges, McDonald turned the question around and replied: ‘Look, what I don’t approve of is the endless gimmickry that the PDs are indulging in.’ Asked if she would wear an ‘IRA – UndefeatedArmy’ T-shirt, she deftly responded that she did not wear T-shirts at press conferences.45

An Irish Times/TNS mrbi opinion poll published on 21 March surprised many when it showed McDonald ahead of outgoing Green Party MEP Patricia McKenna in a battle for the last seat in Dublin. The election team of Fianna Fáil’s Eoin Ryan were watching McDonald like hawks. When they discovered that she had described herself as a ‘peace negotiator’ and ‘full-time public representative’ on the ballot-paper, they complained to the Returning Officer’s staff. Ryan said:

I am not aware of any position to which Ms McDonald has been elected by the public. Her claim to be ‘a peace negotiator’ requires clarification. What peace has she negotiated and with whom? If she can describe herself as a peace negotiator, then so is every member ofOireachtas Éireann. The Sinn Féin candidate’s claim to have been elected by the people to any office is utterly bogus.46

However, the Returning Officer said there were no formal rules as to what titles could be used by candidates, other than people claiming to represent parties which did not exist. Mark Hennessy observed in the Irish Times on 2 June 2004 that Sinn Féin’s policy on the European Union had developed from outright opposition to ‘critical engagement’. Noting that the party’s best hope for success in the election was Bairbre de Brún in the North, he added: ‘One seat in the Republic would be a tremendous result.’

The European and local government elections took place on 11 June, and McDonald won the fourth and final seat in the Dublin Euro-constituency to become the party’s first MEP in the 26 counties. Fianna Fáil, Fine Gael and Labour all held their Dublin seats but McDonald beat the Green Party’s Patricia McKenna into fifth place, with 60,395 first preferences compared to the latter’s 40,445. McDonald’s share of the vote at 14.32 per cent was more than double the 6.64 per cent that Seán Crowe scored for Sinn Féin in the same constituency at the previous European election in 1999.47 It was the small hours of the morning when her election was announced, and Frank McNally captured the atmosphere of the occasion in his report:

Mary Lou McDonald was carried shoulder-high from the RDS count-centre early yesterday. Outside, right on cue, a ghetto-blaster struck up the old Country and Western favourite: Hello Mary Lou (Goodbye Heart). But, the habitual noisy part of the Sinn Féin celebrations over, the new MEP then called her campaign workers into the sort of huddle favoured by football teams. It was a larger huddle than any football team’s, because Sinn Féin have a lot of workers, and McDonald happily acknowledged her debt to them. Among other things, she assured the huddle that this was not Mary Lou McDonald’s seat – it belonged to Sinn Féin. Even at 3.30 am, the message was unblurred and the campaign zeal unrelenting.48

Transfers are of major importance in the Irish electoral process. It has always been a major challenge for Sinn Féin candidates to attract second or other preferences in the system of Proportional Representation. But McDonald broke through the barrier on that occasion. And as well as winning two seats in the Strasbourg parliament, Sinn Féin doubled its representation on the local authorities. The following month, it was announced that the new Sinn Féin MEPs would be part of the United European Left/Nordic Green Alliance (GUE/NGL). Sinn Féin had hosted a Belfast visit by the group the previous March. A high proportion of its members were communists or former communists. However, Bairbre de Brún said this would not affect Sinn Féin support in the US: ‘I think people in America will take a commonsense approach.’ At time of writing GUE/NGL also includes the Greek ruling party, Syriza, Spain’s Podemos and an Independent MEP for the Midlands-North-West constituency in Ireland, Luke ‘Ming’ Flanagan.49

There is no such thing as government and opposition in the European Parliament, so committee membership is vitally important. McDonald was appointed to the committee on Employment and Social Affairs, as well as becoming a substitute member of the committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs. After the election campaign, the new MEP was back in the eye of the storm when she was among those who carried the coffin of Joe Cahill, one of the founders of the Provisional IRA, who died on 23 July 2004. A letter-writer in the Irish Times said: ‘Pictures of Mary-Lou McDonald carrying the coffin of that monster Joe Cahill shocked me to the bone.’ The letter concluded: ‘I want my vote back!’ The episode surfaced again in a Sunday Independent article by Emer O’Kelly on 24 October 2004, under the headline: ‘We should start to see Mary Lou as the enemy’. Italy’s Rocco Buttiglione had been nominated as the EU’s Justice Commissioner but his conservative Catholic views on homosexuality and the role of women in society aroused opposition among MEPs. O’Kelly wrote:

One of those questioning (and indeed damning him) was that well-known defender of civil liberties, Ms Mary Lou McDonald, Sinn Féin MEP...She is a representative of the political wing of a subversive private army dedicated to the overthrow of the Irish State...When Joe Cahill, described as a ‘veteran republican’ died a few months ago, just weeks after Ms McDonald was elected to Europe, she helped carry his coffin to the grave. Cahill’s republicanism, veteran or otherwise, included a string of murders ar son na h-Éireann [Trans: on behalf of Ireland].

The Minister for Justice in the Fianna Fáil-Progressive Democrats government at the time, Michael McDowell, appeared on Today FM’s Sunday Supplement show with McDonald on 17 October 2004. When he said the IRA Army Council made all the key decisions for the republican movement and that senior figures in Sinn Féin were members of that body, McDonald challenged him to name them. McDowell replied: ‘If you really did want me to name them, you would then accuse me of trying to wreck the peace process.’ McDonald said: ‘I have no balaclava. Sinn Féin is a democratic party and we are part of the political mainstream. Sinn Féin is no safe haven for criminality.’50

Sinn Féin was caught up in a whole range of controversies throughout 2005. Possibly the most damaging, because of the horrific circumstances, was the murder of thirty-three-year-old father of two, Robert McCartney, from the mainly-nationalist Short Strand area, who was attacked outside a Belfast pub on the night of 30 January 2005. Republicans were blamed for the killing, and the dead man’s sisters launched an international campaign to achieve justice. The incident was condemned by Sinn Féin and there was a bizarre statement by the IRA that it was willing to shoot McCartney’s killers. Prior to the party’s ardfheis in March of that year, McDonald said: ‘Sinn Féin couldn’t have been more crystal clear in our condemnation of that murder and calls for people to come forward with information.’51

On 9 May 2005, McDonald and de Brún found themselves isolated at the European Parliament, when a motion condemned the McCartney murder and also criticised Sinn Féin for alleged failure to cooperate in the investigation. MEPs backed the resolution by 555-4, and there were 48 abstentions. Unionist MEPs joined with colleagues from an Irish nationalist background in supporting the proposal. McDonald and de Brún backed a separate motion that was less critical of the party and the IRA, but which supported the McCartney family’s efforts to bring those responsible to trial.52

The next Irish general election was very much on the party’s mind, and McDonald was being groomed for the Dublin Central constituency although another Sinn Féin candidate nearly took the seat on the previous occasion. In the previous general election in 2002, Councillor Nicky Kehoe, a former republican prisoner, only missed out by 57 votes. Normally, a candidate with such strong local support would be expected to run again, but it was clearly a Sinn Féin priority to get McDonald into the Dáil. Kehoe supporters were reported to be unhappy with the leadership decision.

An unsigned profile of McDonald published in Phoenix magazine on 12 August 2005 stated: ‘Cllr Nicky Kehoe had looked to be a shoo-in for Dublin Central following a near-miss in 2002 and a huge vote in the locals (3,609 first preference votes in Cabra-Glasnevin)... McDonald had at one stage been suggested as a candidate for Dublin West, her former base when she was a member of Fianna Fáil, but it now looks as if she will be proposed for Dublin Central.’

Sinn Féin opted to run her in that constituency and the party’s hopes were high that she would win a Dáil seat, as part of a significant increase in Sinn Féin representation at Leinster House. Niamh Connolly wrote in the Sunday Business Post: ‘There is serious tension with supporters of local election poll topper Nicky Kehoe, after McDonald was chosen to run in Dublin Central ahead of him.’53 Accompanying McDonald as she carried out an election canvass, journalist Tom Humphries observed: ‘There is a strange dissonance between the knee-jerk media response to Sinn Féin’s engagement in southern politics and the response Mary Lou gets on the doorsteps.’54 A further Phoenix profile, published on 18 May 2007, six days before the general election, said:

Can Mary Lou win a seat in the Taoiseach’s constituency?... Last October a poll commissioned by the Irish Mail on Sunday seriously unnerved Dublin Sinn Féin activists, showing her on just 6 per cent, behind the Green Party’s Patricia McKenna (7 per cent), Labour’s Joe Costello TD (11 per cent) and Fine Gael’s Cllr Paschal Donohoe (12 per cent). Other polls indicated that this was not a rogue poll and it appeared that while doughnutting with Adams at meetings in Downing Street, Stormont and elsewhere was good for the image, it was no substitute for hard graft in Ballybough and Summerhill... Since October it has been a six-and-a-half day week in Dublin Central for McDonald...

The general election took place on 24 May and, as the votes were being counted, it became clear that Sinn Féin candidates were doing quite poorly. There was a strong expectation, for example, that McDonald herself would succeed, but that was to underestimate the Taoiseach of the day and master of the electoral arts, Bertie Ahern, whose transfers in Dublin Central were critical in getting party colleague Cyprian Brady over the line, although the latter had only received 939 first preferences. McDonald got almost 1,800 fewer first preference votes than Nicky Kehoe had secured in 2002 on a slightly lower overall turnout. It was a serious blow in personal terms, and she told Banotti later: ‘When the fateful day arrives and the result is disappointing, it is gutting, it is very difficult personally.’ She went on a family holiday to Spain to get over it, but said in the same interview that, whether winning in 2004 or losing in 2007, ‘I found it an incredibly long process afterwards to try and get my head back together again’.

McDonald’s next electoral outing was in the European elections of 2009. A by-election was scheduled for the same date in Dublin Central to fill the vacancy left by the untimely death from cancer of the radical Independent TD Tony Gregory. Sinn Féin opted to run McDonald again for Europe, despite the fact that the Dublin Euroconstituency could now only elect three MEPs instead of the previous four. As its Dáil candidate the party ran Christy Burke, a long-time member of Dublin City Council and former republican prisoner.

Having won the last of four seats in the Dublin Euro-constituency in 2004, it was always going to be a challenge for her to get re-elected five years later, when the number of MEPs was reduced. McDonald did not retain her seat, and Burke likewise failed to get elected to the Dáil. But the local elections were held the same day and Burke kept his Council seat, then quit Sinn Féin three days later. In a piece on 3 December 2010, Phoenix magazine commented: ‘What galls many party members is that she could have won a Dáil seat in the last election if the right decisions were taken... McDonald failed to win a seat that Kehoe would have won in Dublin Central and Sinn Féin’s Joanna Spain lost in [Dublin] Mid-West where McDonald would also have won had she been a candidate.’

But she ran again for the Dáil in Dublin Central, in the 2011 general election. Fianna Fáil were at a low ebb, and Ahern wasn’t running this time. When the votes were counted, McDonald was the last of four TDs to be elected. Christy Burke, running as an Independent, didn’t help – he got 1,315 first preferences.55 In 2012 on the TV3 political talk show, Tonight with Vincent Browne, Deputy McDonald was chosen by a panel of assessors as ‘Opposition Politician of the Year’. Mary Lou’s career was back on track. But although the speculation continued, there was no sign of Gerry Adams moving aside for the republican from Rathgar.