Читать книгу Power Play - Deaglán de Bréadún - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

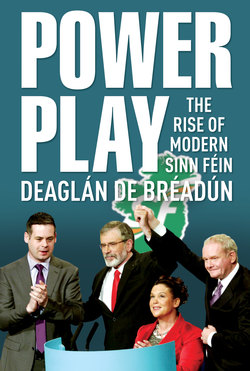

Оглавление1. WE NEED TO TALK ABOUT SINN FÉIN...

‘Something is happening here, but you don’t know what it is, do you, Mister Jones?’ (Bob Dylan)

THERE ARE MANY PEOPLE, including members of other political organisations, who don’t want to give Sinn Féin a mention, at least not in any way that might allow the party a competitive advantage. Some of them are adherents of Leon Trotsky, but even they would have to acknowledge the truth of their master’s dictum: ‘You may not be interested in war, but war is interested in you.’

Except, of course, that Sinn Féin is no longer at war. Or rather, it is no longer the propaganda voice of the ‘armed struggle’ carried out by the Provisional IRA. That campaign is over, according to the Independent Monitoring Commission (IMC), established by the British and Irish Governments as part of the peace process. When I asked the Commissioner of the Garda Síochána (‘Guardians of the Peace’), the Republic of Ireland’s police force, Nóirín O’Sullivan, on 24 April 2015, if the IMC assessment was still valid, she replied: ‘Absolutely. The report of the International Monitoring Commission, that still stands. They reported that the paramilitary structures of the IRA had been dismantled.’ Speaking in Dublin to the Association of European Journalists, Commissioner O’Sullivan added that individuals, ‘who would have previously had paramilitary connections’, were currently involved in criminal activity, especially along the border between the two parts of the island. The Commissioner was echoing the words of the IMC. It stated, in its 19th report, issued in September 2008: ‘Has PIRA abandoned its terrorist structures, preparations and capability? We believe that it has.’ Following two Belfast murders in the summer of 2015 the Commissioner was asked to review the situation for the Government (see also Epilogue).

While the IRA, or individual members, may still allegedly strike out on occasion, the ‘Long War’, as the Provisionals called it, is officially over. As a result, Sinn Féin has gone from being the Provos’ brass band, to becoming a key player in mainstream politics, north and south. Since 1999, with a gap of a few years, Sinn Féin ministers have been part of the power-sharing administration in Northern Ireland. For the last eight years, as the second-largest party in the Stormont Assembly, Sinn Féin has held the post of Deputy First Minister, in the person of former IRA leader Martin McGuinness.

South of the border it is, at time of writing, the second-largestparty in opposition, with 14 out of 166 members in Dáil Éireann, and three Senators from a total of 60 in the Upper House. This significant but still-modest representation is expected to increase considerably in the next general election, due to be held by 9 April 2016 at the latest. At least, this is what opinion polls have been suggesting for some time. In the last general election, held on 25 February 2011, the party secured 9.9 per cent of first preference votes, under the Irish system of proportional representation. But as it became clear in succeeding months that the new Fine Gael-Labour coalition was implementing similar austerity policies to its Fianna Fáil-led predecessor, elements of public opinion began to move towards the ‘Shinners’. The average for nine polls conducted by four different companies in the first four months of 2015, for example, was 21.5 per cent.(May to mid-September average is 19.1 per cent.)

This compares with 25 per cent over the same period for the main government party, Fine Gael; 18.3 per cent for the chief opposition party, Fianna Fáil; eight per cent for minority coalition partner, Labour; and 26 per cent for ‘Others’ – which includes independents and smaller parties. Indeed one poll, conducted by the Millward Brown company and published in the Sunday Independent in mid-February 2015, had Sinn Féin as the most popular party at 26 per cent, one point ahead of Fine Gael. An Ipsos MRBI poll in theIrish Times in late March had the two parties level, at 24 per cent. The average percentages for May-July were: Fine Gael at 26.25; Fianna Fáil at 20.25; Sinn Féin at 19.5; Labour at 7.75; Others at 26.25.

The biggest casualty has been the Labour Party, which scored 19.5 per cent in February 2011 after a feisty election campaign, based on pledges to resist the bail-out terms imposed by the ‘Troika’ of the European Union, International Monetary Fund and European Central Bank (ECB), following the collapse of the Irish banking system in 2008.

The Labour Party leader at the time, Eamon Gilmore, famously said, in relation to the strictures of the ECB on Ireland, that voters had a choice between ‘Frankfurt’s way or Labour’s way’. Labour even deployed the slogan ‘Gilmore for Taoiseach’ during the election, but ended up as the ‘mudguard’ of the next government – it was to be Frankfurt’s way after all. Two polls at the end of 2014 had Labour at a startling five per cent although the position of the party improved over the following four months.

Poll ratings are not always reflected at the ballot-box. You need the organisational structure ‘on the ground’, and people who respond to pollsters don’t always bother to cast their votes, or may not even be registered to vote. Fianna Fáil got 25.3 per cent support in the 2014 local elections although its average opinion poll ratings had not improved to that extent on the 17.45 per cent that the party received at the ballot-box in 2011. Sinn Féin’s performance in the ‘locals’, in contrast, was below what the opinion surveys had indicated.The party nevertheless did well in the same day’s European Parliament elections, where grassroots organisation was somewhat less important.1

Sinn Féin is subject to an unrelenting stream – richly deserved, according to the party’s critics – of negative publicity and unfavourable media coverage, which is mainly related to the behaviour of some IRA members in the past, and how it was dealt with by the movement. But this didn’t seem to inflict any long-term damage: Sinn Féin kept bouncing back. Commenting on the phenomenon in the Sunday Business Post of 26 April 2015, Pat Leahy called Sinn Féin the undeniable ‘coming force in Irish politics’, as shown by the previous two years of polling research. In the same edition of that newspaper, Richard Colwell of the Red C polling company commented upon Sinn Féin’s ability to ‘swat away losses on the back of any controversy just a month later’. He referred to the 4 per cent loss endured by the party ‘on the back of a significant controversy surrounding its handling of alleged sex abusers within its ranks’. That was in the Red C poll published on 28 March but, just a month later, that support returned, leaving Sinn Féin with 22 per cent of the first preference vote. (However, a Red C poll in the 13 September Sunday Business Post had Sinn Féin at 16 per cent.)

Just as Labour did before the last general election, Sinn Féin takes an anti-austerity stance on the issues of the day. This has paid off in terms of support, and looks likely to win extra seats for the party at the next election. Unless there is a very dramatic change in public opinion, a one-party government next time can be ruled out. The Dáil is being reduced in size from 166 to 158 TDs, making the minimum number of Dáil seats required for a majority 79, since the Ceann Comhairle (Speaker) of the House traditionally supports the Government in the event of a stalemate. Fianna Fáil and Sinn Féin would be an unprecedented alliance, as would Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, although they all trace their historical roots back to the original Sinn Féin, founded in 1905. Some observers see Fianna Fáil-Fine Gael as the more likely combination, though this would cause problems among the grassroots membership of Fianna Fáil in particular.

In current discourse, Sinn Féin are, in many ways, the pariahs of Irish politics. That is partly due to genuine revulsion at deeds carried out by the IRA during the Troubles, such as the horrific 1972 abduction of widowed mother of ten Jean McConville from Belfast, whose body was found on a beach in County Louth in 2003. Despite these continuing controversies, the party retains a high standing in the polls, and there appears to be a disconnect between what Sinn Féin’s critics are saying and the mindset of a sizeable proportion of the electorate. This may be due to a perception that, apart from the occasional foray by dissident republicans, the Troubles in Northern Ireland are a thing of the past. It is hard to avoid the conclusion that Sinn Féin supporters share the view expressed by party president Gerry Adams on the McConville case: ‘That’s what happens in wars.’2

Critics of the party tend to forget that Sinn Fein’s IRA associates were part of a very long tradition of republican violence. The Irish Left Review carried a piece by Fergus O’Farrell who pointed out that some of the leaders of the War of Independence 1916-22 were responsible for actions which aroused a similar moral disgust:

More civilians were killed during Easter week than British soldiers or Irish rebels [...] On Bloody Sunday [21 November 1920], the IRA [including future taoiseach Seán Lemass, D. de B.] carried out an operation against what they believed to be a British spy ring in the city – they killed 14 men that morning. As careful historical research has made clear, not all of these men were spies, let alone combatants [...]When the innovative Minister for Finance Michael Collins rolled out the ‘Republican Loan’ to raise money for the establishment of an independent Irish state, the British sent a forensic accountant, Alan Bell, to Dublin to investigate the money trail. Concerned that Bell would scupper the revenue-raising scheme, Collins dispatched members of The Squad to deal with the inquisitive accountant. Bell was escorted off a city-centre tram and executed in the street in broad daylight.

O’Farrell goes on to point out that Fine Gael pays tribute to Collins every year at the place where he was assassinated and that FiannaFáil and Labour have, as their respective icons, Éamon de Valera and James Connolly, both of them part of the ‘tiny, unrepresentative armed group’, whose actions resulted in the deaths of so many civilians in Easter 1916.3

The author of the present book subscribes to the sentiments of the 19th-century nationalist leader Daniel O’Connell, who said that freedom should be ‘attained not by the effusion of human blood but by the constitutional combination of good and wise men’.4The only reservations I would have are in cases where the territory of the state is invaded by some foreign power and, of course, O’Connell’s failure to include women among the ‘good and wise’! Unfortunately, however, a vast quantity of blood has been spilled in pursuit of a 32-county independent Ireland. What makes Sinn Féin interesting these days is that it decided, as part of the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, to end its support for violence in favour of peaceful, democratic, consensual methods. Since I had reported in detail on those negotiations, it seemed worthwhile exploring the political aftermath, and the success or otherwise of what could be described as the biggest shift in the strategy and ideology of Irish republicanism for very many years. At time of writing, the Sinn Féin project seems to be meeting with some success, but this could, of course, change. As someone once said – possibly Mark Twain or perhaps Samuel Goldwyn – ‘Predictions are hard to make, especially about the future’. It is unclear, at present, whether the entire Sinn Féin venture will succeed or run into the sand, but there are valuable lessons to be learnt either way.

Sinn Féin’s rise has coincided with the emergence of Syriza in Greece and Podemos in Spain as major electoral forces. The pronouncements of all three against austerity are very similar and, with Syriza in power in Greece and Podemos knocking on the door in Spain, the prospect of Sinn Féin in government as part of an anti-austerity coalition cannot be ruled out. This may be an appalling vista to elements in the other parties, parts of the media and the middle and upperclasses, but the trade union movement has been taking a keen interest.

Giving an address at Glasnevin Cemetery on 31 January 2015, in memory of ‘Big Jim’ Larkin, leader of the 1913 Lockout in Dublin, the President of SIPTU (Services, Industrial, Professional and Technical Union), Jack O’Connor made what could turn out to be a significant intervention. Predicting that the year ahead would ‘turn a new chapter in the history of Ireland and of Europe’, O’Connor, who leads some 200,000 members, said that the trade union movement would be seeking to retrieve the ground lost during the economic crisis. Among the ‘difficult compromises’ which had been made, he included ‘the call on Labour to step into hell in the current coalition to head off the threat of a single-party Fine Gael government, or worse’. But now, ‘in the light of improving economic conditions’, he was recommending a new strategy. The SIPTU chief welcomed Syriza’s ‘dramatic’ election victory in Greece the previous Sunday, ‘which signals the beginning of the end of the nightmare of the one-sided austerity experiment’. He continued:

Dramatic possibilities are now opening up here in Ireland as we approach the centenary of the 1916 Rising. At this extraordinary juncture, history is presenting a ‘once in a century’ opportunity to reassert the egalitarian ideals of the 1916 Proclamation, which were suffocated in the counter-revolution which followed the foundation of the State. It is incumbent upon all of us Social Democrats, Left Republicans and Independent Socialists, who are inspired by the egalitarian ideals of Jim Larkin and James Connolly, to set aside sectarian divisions and develop a political project aimed at winning the next general election on a common platform – let’s call it ‘Charter 2016’.

Pointing out that this would be ‘the first left-of-centre government in the history of the State’, the SIPTU chief continued by calling upon parties and individuals on the Left to not simply ‘do well in the election’, but to display ‘a level of intellectual engagement around policy formation, free of the restrictions of sectarian party political interests’. The point was to secure a Dáil majority for the Left, which needed to set these differences aside and ‘seize the moment’.

There was no mention of Sinn Féin in the speech, and the only reference to the Labour Party was in the context of the previous general election. But an alliance of ‘Social Democrats, Left Republicans and Independent Socialists’ could only mean those two parties along with others from the ‘broad left’ among the Independent TDs, as well as their followers and co-thinkers.5The speech was welcomed in a statement later that day by Senator David Cullinane, Sinn Féin’s spokesman on trade union issues, who said that his party was ‘committed to forming broad alliances with parties and independents to maximise the potential for an Irish Government that is anti-austerity’.6

Next day, Justine McCarthy reported in the Irish edition of the Sunday Times that Sinn Féin had been in talks for more than two months with trade unions, left-wing groups and independent TDs to agree a platform for the general election, with the talks gaining impetus from Syriza’s election victory in Greece the previous weekend. Union officials and co-ordinators of the Right2Water campaign against the water charges, Brendan Ogle of the Unite trade union and Dave Gibney from Mandate,were named as two of the ‘key promoters’ of the talks. TD Richard Boyd Barrett, a member of the Socialist Workers’ Party, a Trotskyist group, was quoted as backing the talks. He added, though, that ‘Sinn Féin have to decide whether they’re building a specifically Left project or whether they just want to be in government.’

Another Dáil deputy, from a different wing of the Trotskyist left, Joe Higgins of the Socialist Party (SP), said that his organisation was not involved in the talks, and wouldn’t be prepared to make an election pact with Sinn Féin which was not a party of the left and was ‘taking an anti-austerity position in the South while implementing austerity in the North’. 7The SP also has a different approach on the national question and its position was set out in greater detail in its newspaper, The Socialist:

Jack O’Connor, leader of the South’s biggest union SIPTU, has been openly courting Sinn Féin. SIPTU are affiliated to the Irish Labour Party, and its support has collapsed as it has been implementing massive austerity as part of the Southern coalition government. North and South the union leaders, rather than organising a real concerted struggle against the austerity being implemented by both governments, would rather back the likes of Sinn Féin in order to get a few crumbs from the table.8

Writing in An Phoblacht (The Republic), Sinn Féin’s chairman Declan Kearney, a key party strategist, said that the basis for going into government in the South should be the advancement of ‘republican objectives’, and not simply entering coalition for its own sake. He added that ‘formal political discussion should commence on how to forge consensus between Sinn Féin, progressive independents, the trade union movement, grassroots communities, and the non-sectarian Left’. These talks should focus ‘on the ideas and strategies which will ensure the future election of a Left coalition in the South dedicated to establishing a new national Republic’.9

Meanwhile, in the Sunday Business Post, Pat Leahy reported that ‘Sinn Féin is moving to formally rule out coalition as a minority partner with either Fianna Fáil or Fine Gael after the next election’. He said that a motion was expected to go before the party’s ardfheis (national conference) in early March, with backing from the ardchomhairle (national executive committee), mandating the leadership to this effect.10About two weeks after O’Connor’s Glasnevin speech, Sinn Féin sent out a press notice that Adams and Deputy Leader Mary Lou McDonald would be ‘available for media comment on key challenges facing people prior to the general election’. It was what we media folk call a ‘doorstep’, ahead of a Sinn Féin meeting at the Teachers’ Club in Dublin’s Parnell Square. Perhaps because it was held in the evening there were only two journalists present, myself and a colleague from one of the daily papers.

I asked Adams what kind of line-up Sinn Féin would be prepared to accept, in the event of a coalition being on the table, and assuming there could be agreement on a common programme before taking office. Replying that a Sinn Féin majority government would be the party’s first preference, he continued:

First of all, I see this very clearly in two phases, and the first phase is to get the biggest possible mandate for Sinn Féin. That will, of course, influence the other parties; that will perhaps, in some way, determine how the other parties get on as well. The second phase is to negotiate a programme for government. And clearly, given our politics, there’s an incompatibility between our position[and], say, for example, [that of] Fine Gael. Also, one of the big benefits of Labour being in government, for other political parties, is that you learn not to do what they have done, which is [for] a minority party to append itself to a senior partner, a conservative party. So we will not do that. And, actually, even though I understand the legitimacy of the question, I actually don’t think there’s much point, given that the people haven’t voted. We have to be humble; it’s the people’s day, they will decide who will form the government. So, mandate first, programme for government second. And we’ll decide on the basis of that.

He welcomed Jack O’Connor’s remarks, especially where the SIPTU leader said the type of government he was proposing wouldn’t be able to do everything at once, and would have to set priorities. He continued as follows: ‘If we were able to, in one sentence, say our preference, it has to be an anti-austerity government, which may be wider than the Left. Who knows who’s going to come out of, you know, the [general election]... Shane Ross is certainly anti-austerity. Who knows, among the Independents, who might come out of all of that. But again I’m making the mistake of speculating about all of that.’

Formerly a member of Fine Gael, Shane Ross was elected to the Dáil in 2011 as a non-party Independent TD, and took the lead in forming an alliance with other Independents, some of them on the Left, with a view to working out a deal with the next government, possibly in return for cabinet seats. In an issue published the day after Adams spoke to me, the Phoenix, a magazine which takes a close interest in the internal life of the republican movement, outlined a possible scenario whereby Sinn Féin could be the largest element in an anti-austerity group in coalition with Fianna Fáil:

Behind the scenes, Sinn Féin activists, including the leadership, are planning a coalition proposal that could get round the problem of being a minority party in government. The strategy – based on the acceptance that Fianna Fáil would have more seats than Sinn Féin – is to create a post-election alliance of Sinn Féin with Left Independents and even Labour. On a rough calculation that sees Fianna Fáil with 35 seats; Sinn Féin 30; Left Independents 10 and Labour perhaps 10, such a coalition would have a majority of 80-plus seats out of 158 in the next Dáil. But it would also see such an alliance having more than Fianna Fáil. This would allow Sinn Féin[…] to argue that the Left Alliance was the largest part of such a coalition with a mandate for a left programme in government.11

In the Sunday Times, Justine McCarthy reported that union leaders Brendan Ogle and Dave Gibney had met at Leinster House with a Sinn Féin group, headed by deputy leader Mary Lou McDonald, to discuss a left-wing, pre-election alliance:

The meeting opened on a confrontational note. The previous Sunday, addressing a party meeting in Mullingar, Sinn Féin president Gerry Adams had welcomed a call by the SIPTU president Jack O’Connor, for the Irish left to unite on ‘a common platform’. There is a sharp divergence of both style and strategy between SIPTU, which has about 200,000 members and is officially affiliated to the Labour Party, and other unions such as Mandate and Unite, which are commonly branded ‘militant’. In his Mullingar speech, Adams said that elements of the trade union movement must end their ‘unrequited support’ for Labour. Ogle and Gibney regard Labour as toxic and having scant hope of being in the next government. To them, SIPTU is backing a loser. SIPTU and Labour are joined at the hip, they warned Sinn Féin[…]The most immediate bone of contention between SIPTU and the Right2Water unions is water charges. SIPTU, which counts water utility workers among its members, believes there is a need for water charges and an administrative structure. The others are campaigning for the abolition of charges and for water to be funded by progressive taxation.12

The following day, the Right2Water unions announced a two-day conference for the start of May. This was later changed to ‘an international May Day event’, followed by a policy conference nearly two weeks later, on 13 June. Both occasions would be by invitation only, due to space restrictions. The May-Day event would feature speakers from the European Water Movement, as well as from ‘progressive grassroots movements’ such as Podemos and Syriza. The policy conference would ‘discuss a set of core principles which will underpin a “Platform for Renewal”in advance of the next General Election. These core principles will be the minimum standards a progressive government will be expected to deliver in the next Dáil’.13Adams issued a statement welcoming the initiative: ‘It mirrors my own suggestion of a Citizens’ Charter, encapsulating the fundamental principles that could take us towards a citizen-centred, rights-based society.’ In his Glasnevin speech, O’Connor had suggested something similar, with the title of ‘Charter 2016’. The terms set out by Adams had a flavour of Syriza and Podemos about them: ‘Such a charter could be endorsed by various progressive political parties and independents, community groups and trade unions in advance of the next election. This would not compromise any political group, and does not imply any electoral pact. I believe that a Citizens’ Charter could form the basis for a new departure in Irish politics.’

The Labour Party’s annual conference took place in Killarney on the last weekend in February, and a number of Labour ministers, as well as Jack O’Connor, were on the panel for the Saturday with Claire Byrne show on RTÉ Radio 1. When asked about the SIPTU leader’s proposal, Environment Minister Alan Kelly said: ‘Sinn Féin aren’t a left-wing party. They’re a populist movement with a Northern command.’ Expressing security concerns, he said he didn’t believe, as deputy party leader, that Labour would be negotiating a partnership in government with Sinn Féin: ‘How can you do that credibly when the first thing on the agenda of whoever is doing so would be the fact that the Department of Justice, Defence and probably Foreign Affairs would be vetoed away from them?’

The SIPTU leader responded: ‘In my engagement, since I became president of our union in 2003, with the leaders of Sinn Féin, I believe them to be very good and well-intended people. I believe that Sinn Féin has many socialists in it. I believe that we could work with them.’ But O’Connor said he did not foresee any break in the formal link between his union and the Labour Party. (In the May 2014 local and European elections, for example, Labour candidates received a total of €20,040 from the union as well as paying an annual affiliation fee of €2,500.14) At a news conference a few days later, when I asked Mary Lou McDonald for her response to Minister Kelly’s claim that Sinn Féin was run by a ‘Northern command’, she replied: ‘We don’t operate to a command structure. We are thoughtful, free-thinking individuals who, each in our own way and in our own time, has chosen freely and voluntarily to be part of this great political party and this great political project […] There are no sheep, and there is nobody who takes commandments from on high.’

In the March edition of An Phoblacht, columnist and aspiringSinn Féin TD, Councillor Eoin Ó Broin, noted O’Connor’s call for Left unity and the separate initiative of the Right2Water unions in hosting a conference to shape a common political platform. He asked:

Can we really build that ever-elusive Left unity? Divisions between the anti-austerity unions and those supportive of the Government run deep. Will SIPTU be invited to attend the May Day ‘Platform for Renewal’ dialogue? […] And is it possible to have an anti-austerity government without the involvement of the Labour Party and the socially-liberal constituency they represent? […] It is time for the Irish Left to build common ground. We have a very rare chance to build a real alternative to the status quo, to be part of a new politics, a new political economy, a new Republic. Let’s not waste that chance.

Delegates at the Sinn Féin ardfheis, held in Derry between 6 and 7 March, unanimously backed a motion that the party would not enter into a coalition government led by either Fine Gael or Fianna Fáil. It was jointly proposed by branches ranging from Donegal to Corkand Roscommon to Dublin. Ó Broin told delegates:

We can start to build an Ireland of equals, a united Ireland, a better, fairer Ireland. But this can only happen if Sinn Féin makes a clear and unambiguous statement that we will not under any circumstances support a government led by Fianna Fáil or Fine Gael... If Sinn Féin can lead a government that invests in a fair recovery, in secure and well-paid jobs, in universal public services, in strong and vibrant communities, in a real republic that is committed to ending poverty and inequality – then and only then should our party be willing to take up residence in Government Buildings.15

It could well be that a coalition is negotiated in which Sinn Féin would numerically be the largest party. That would fulfil the terms of Motion 52 at the ardfheis. But the alternative scenario, cited earlier in this chapter, whereby Sinn Féin might not be the biggest party overall but would be the largest element in an anti-austerity majority, would arguably still be a permissible option. Much would of course depend on who held the office of taoiseach (prime minister). In the past, there had been talk of a ‘rotating taoiseach’ between Labour and its coalition partner. Motion 52 committed Sinn Féin ‘to maximise the potential for an anti-austerity government in the 26 Counties’. A profile of Adams in the Phoenix had reported north-south tensions within Sinn Féin on the coalition issue. The article, published on 13 December 2013, stated:

Adams and his closest comrades are more susceptible to coalition government with, say, F[ianna]F[ail] than those southern Sinn Féin activists who have little obvious IRA baggage […] The party organisation is still dominated by northern members whose position on party policy can differ from the southerners and certainly will, when the question of coalition in the Republic comes to the fore. The fear among some southern Sinn Féin activists is that the price Sinn Féin leaders would pay in any coalition negotiations for a Sinn Féin-led hands-on government approach to the North would be concessions on the economy and taxation.

The manner in which Sinn Féin surpassed Fianna Fáil on many occasions in the opinion polls and in the number of seats won in the May 2014 European elections was, of course, galling for a party which had been the sole or majority holder of government office for a total of sixty-one years since 1932. Small wonder, then, that Micheál Martin’s position as Fianna Fáil leader was being questioned.

Never slow to highlight Sinn Féin’s deficiencies as he saw them, Martin launched a multi-pronged assault on the rival party in mid-April 2015. He hit out at Sinn Féin on RTÉ’s Late Late Show, then in the course of a massive double-page interview with the Sunday Business Post and, later the same day, in his annual leader’s speech at the Fianna Fáil commemoration in Arbour Hill – the Dublin cemetery where the 1916 leaders are buried – and finally in a radio debate with Adams.He told Late Late Show presenter Ryan Tubridy that Fianna Fáil would not be going into coalition with Sinn Féin ‘in any shape or form’. Martin added that Sinn Féin was ‘a cult-like group in many respects, and you don’t get diversity of opinion’. He also ruled out government with Fine Gael because that party ‘have gone too right-wing for us’. In his Sunday Business Post interview, he said Sinn Féin was seeking to ‘undermine the very institutions of the state’.16

The Fianna Fáil leader’s speech to the party faithful at Arbour Hill was exactly 3,000 words long, but almost half of these were devoted to a critique of Sinn Féin (there was no mention of Fine Gael or Labour). He claimed that Sinn Féin was making ‘a deeply sinister attempt to misuse the respect which the Irish people have for 1916’. Martin said it was a ‘false claim that they have some connection to 1916 and to the volunteers who fought then’. This was part of a Provo agenda to ‘claim legitimacy for the sectarian campaign of murder and intimidation which they carried out for 30 years’. He continued: ‘This goes to the heart of why Sinn Féin remains unfit for participation in a democratic republican government.’ The Provos had killed ‘servants of this republic’ (members of the Irish security forces) and Sinn Féin was selling T-shirts with the slogan ‘IRA – Undefeated Army’.17

The Fianna Fáil leader won plaudits from Sunday Independent columnist Eoghan Harris, who wrote: ‘Martin’s polemic against the Provos came from deep in his personal moral core. It called to mind Jonathan Swift’s saeva indignatio, the savage indignation of which W.B. Yeats wrote so movingly.’18Given the tone and length of Martin’s Arbour Hill condemnation, it was inevitable that Adams would feel it necessary to respond in a formal way and in some detail. Normally, the media are informed by email, or at least by text message, in advance of Sinn Féin events that are open to them. But this one was clearly arranged in some haste for the following Wednesday. I was talking to some Sinn Féin staff and politicians in Leinster House when they mentioned ‘Gerry’s keynote speech’ which would be given in a place with the not-very-republican title of Royal College of Physicians of Ireland, a handsome building close to Leinster House.

When I worked as a reporter in Northern Ireland, the Republicans habitually arrived late for press and other public events, and the journalists consoled themselves for the long wait with the wry observation: ‘We’re on Sinn Féin time.’ This is not the case any more, in my experience, and the hall was full at 7pm, when the meeting was due to start. Members of the Sinn Féin parliamentary party were there in strength and sitting at the front. All the leading figures from the Dublin area appeared to be present, including some holding prison records for IRA activities. Adams began his speech with the usual digs at Fianna Fáil’s record in government, where Martin was a cabinet minister for 14 years, and then got to the nub of the matter:

Micheál Martin also raises the hoary old myth of there being a good Old IRA in 1916 and in the Tan War, and a bad IRA in the 1970s, the 1980s and the nineties. Of course, he ignores the reality that Volunteers in 1916 were responsible for killing women and children here in the streets of Dublin and that, through the Tan War, the IRA was responsible for abducting, for executing and secretly burying suspected informers. But he tries to sanitise one phase of war and demonise and criminalise another one. So let there be no doubt about it, war is terrible. All war. War is desperate. And those of us who have lived through the recent conflict are the ones who have worked to ensure that the conflict is ended for good, and that we never – none of us, ever – go back there again. And that’s why Sinn Féin is and was pivotal to the peace process. So those of us – and people died in this city also –but those of us who have come from communities that were ravaged by conflict, those of us whose neighbours were killed, those of us who buried our friends and our family members, who carry injuries to this day, those of us in this state and in the Northern State and in Britain and elsewhere who endured the prisons: we don’t need lectures from Micheál Martin or anyone else about conflict. We have been there [prolonged applause, whistling and cheering]. Let me say this: Republicans did not go to war: the war came to us. So there is an obligation on political leaders to work to resolve conflict, to build reconciliation, not to fight a false war, not to refight a false and scammy-type rhetorical approach at looking at the past in a totally skewed way. Micheál Martin needs to wake up and realise that the war is over. It’s now time to build the peace [applause]. But there has to be a dividend, an economic and social dividend in the peace for everyone, not just in the North but here in this state also. So his selective lookbacks on Irish history convince no one [pause]. We at least are consistent. We are as proud of Bobby Sands and Mairéad Farrell as we are of the Volunteers of 1916, and those who fought the Black and Tans [applause].

The meeting ended after the speech, which lasted twenty minutes. Outside in the corridor, a glass case held mementos of Napoleon Bonaparte, who also knew a thing or two about conflict, albeit on a wider scale. Sinn Féin people said they had been anxious to rebut Martin’s attack on them, but without alienating the Fianna Fáil grassroots. Indeed, Adams said in his speech that he had spoken to long time Fianna Fáil activists, who were ‘disappointed’ and ‘disillusioned’ because the leadership had ‘strayed from its original republican origins’. A Sinn Féin TD told me that Fianna Fáilers in his constituency were unhappy with their party leader’s remarks, as they were hoping to get Sinn Féin transfers in the next election.

All’s fair in love and war and, arguably, Martin needed to have a few swipes at Sinn Féin, not only to express strongly-held convictions, but to shore up his leadership and stop ‘Adams and Co’ from nibbling away at Fianna Fáil’s support. Martin’s position in the party had been under some pressure, due to poor poll showings. His Arbour Hill oration came a week ahead of the annual Fianna Fáil ardfheis (national conference) and a month before a by-election in the Carlow-Kilkenny constituency, where it was considered critical for Martin’s future that Fianna Fáil should take the seat – as it did by a comfortable margin.

There is polling evidence that, between them, Sinn Féin, Fianna Fáil and Labour could end up with a majority in the Dáil. However, as Martin pointed out on the Late Late Show, Sinn Féin’s performance in the 2014 local elections was significantly lower than the opinion surveys suggested, whereas Fianna Fáil did better than the polls had indicated beforehand. In any case, given Martin’s constant denunciations of Sinn Féin and what he calls ‘the Provisional movement’, it would be quite a turnaround if he somehow ended up in government with them. In the past, however, the Progressive Democrats and the Labour Party slated Fianna Fáil without mercy, but then decided that their best course of action was to join them at the cabinet table.

At a press conference during the Fianna Fáil ardfheis in the Royal Dublin Society (foreign observers must wonder at the number of places in this Republic with the word ‘royal’ in their titles) on the last weekend of April 2015, I asked Martin what his approach would be in the next Dáil, given that he had ruled out coalition with Fine Gael and Sinn Féin. He replied:

We’re going to fight the election first, Deaglán, and we’re going to fight the election on the issues, which I think is a legitimate position to have. And I have said this to a number of journalists who have been interviewing me in recent times. The debate moves very quickly on to a post-election scenario, as if it’s already happened. It hasn’t happened: we haven’t had the general election. We have to fight the election on the issues and that’s what we’re doing, in terms of the policy issues … and we’re going out there to maximise our vote and our seats so that we can influence, in whatever way that may turn out, the implementation of those policies.

One of Martin’s colleagues later told me that Fianna Fáil had worked out, in fairly precise terms, that Fine Gael stood to lose 22 out of its 69 Dáil seats, and Labour would go down by 16 seats from 34 to 18. (Most observers would find the Labour prediction rather optimistic.) The priority was to ensure that as many of these lost seats as possible went to Fianna Fáil. The attacks on Sinn Féin were motivated by the perception that a good deal of Sinn Féin’s support was ‘soft’, and could be swayed in Fianna Fáil’s direction. Speaking on condition of anonymity, this member of the parliamentary party said there was a strong possibility the next election would result in a minority government which would not last long and that the Dáil would be dissolved again fairly quickly. He ruled out coalition with Fine Gael, but felt that an agreement between Fianna Fáil and an anti-austerity grouping led by Sinn Féin was a real possibility, despite what his party leader was saying. Other parties in the past had denounced their opponents and then gone into government with them: that’s the way the game was played.

Another prominent party figure from a rural area said the attacks on Sinn Féin had been a good idea, but that it was nevertheless likely there would be a Fianna Fáil-Sinn Féin coalition in the end, although he pointed out that any coalition proposal would be subject to approval by a special Fianna Fáil ardfheis. Meanwhile, a prominent Fianna Fáil stalwart based in a Dublin constituency said the party should remain in opposition, as a tie-up with Fine Gael would mean that about one-third of the membership would drop out, and another third would start looking to Sinn Féin. He said that, apart from some office-hungry TDs, there was little appetite for coalition with Sinn Féin either.

The prospect of a coalition involving Fine Gael and Sinn Féin would appear, on the surface at least, to be even more remote. The idea was floated in the past by a senior Fine Gael advisor at the time, Frank Flannery, but this was before the change of mood, symbolised by Syriza, came about in European politics. In the aftermath of the 2007 general election, when no party had a clear majority, Sinn Féin publicly urged Enda Kenny to contact the party for discussions.Cavan-Monaghan TD Caoimghín Ó Caoláin told interviewer RóisínDuffy on RTÉ radio’s This Week programme, on 10 June 2007, that Sinn Féin was ‘very open-minded’ as to who should become taoiseach, because the real issue was the programme for government.

That would be quite a turn-up for the books and might well cause problems with some of the unions, but past experience shows that anything can happen when political power is at stake.19

When the election does take place, one of Sinn Féin’s greatest challenges will be to win transfers from voters whose first loyalty is to other parties. The Irish system of proportional representation means that the electorate can vote for candidates in order of preference. When the first choice from the ballot paper is either elected with a surplus of votes over the quota or else eliminated, the vote may be transferred to the second choice. If the second choice is elected or eliminated, the vote may be transferred to the third choice, and so on. Given the continuous attacks on Sinn Féin in the Dáil and the media on issues ranging from the abduction of Jean McConville to the manner in which the republican movement is said to have dealt with allegations of sexual abuse by IRA members, Sinn Féin may well find it difficult to get transfers in the general election. However, the party looks set to be a much stronger presence in the next Dáil. There is no evidence at this stage to suggest it will be a bigger party than Fine Gael, but some of the poll evidence suggests that it could give Fianna Fáil a run for its money. Whether it will have a prospect of entering government on satisfactory terms is very much up in the air. It seems safe to say that, once the results are in, Sinn Féin will have moved further from the margins, and closer to the mainstream, in Irish political life.