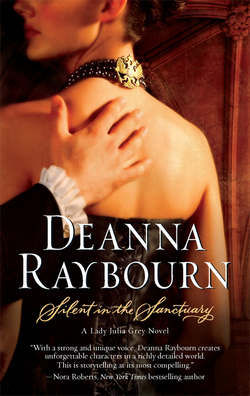

Читать книгу Silent in the Sanctuary - Deanna Raybourn, Deanna Raybourn - Страница 6

ОглавлениеTHE SECOND CHAPTER

Britain’s a world by itself.

—CYMBELINE

There are few undertakings more challenging than planning a journey for one’s family. It is a testimony to my good nature and sound common sense that I arranged our return to England without resorting to physical violence. Violante, who had raged and howled against not being taken to England to meet her new family, decided she had no wish to leave the land of her birth and commenced to weeping loudly over each meal, watering her uneaten food with her tears. Lysander, always the softest and most malleable of my brothers, persuaded by a sister’s single shimmering tear or outthrust lip, had grown a carapace of indifference and simply went about the business of eating, paying no more attention to Violante than he did the dozen cats who prowled about our loggia, purring for scraps.

Although Plum had joined enthusiastically into the scheme of Christmas at the Abbey, it suddenly occurred to him that he was leaving the fine northern Italian light indefinitely. He spent most of his time in the salon, painting feverishly and ignoring the summonses to meals, contenting himself with a handful of spicy meats tucked sloppily into a hunk of bread and a bottle of wine filched from the cellars. It was left to me to organise our departure with Alessandro’s help. He was invaluable, cheerfully dashing off to deliver a message or secure another cart for our baggage. No task was too menial for him. He wrapped books and tied parcels with as much good humour as he had shown introducing us to the delights of Florence. I sorely missed him when he left us the day before our departure, promising to meet us at the train station in Milan. He was secretive and a little quiet, I thought, but he smiled and kissed my hand, brushing his lips not over my fingers, but across the pulse at my wrist. Before I could reply, Morag managed to drop an expensive piece of porcelain that belonged to the owner of the villa, and by the time I had sorted out whether or not it could be repaired, Alessandro was gone.

The next day we rose early and made the trip into Milan, Plum resplendent in a garish tasselled red fez he had purchased on his travels. Violante sobbed quietly into her handkerchief, blowing her nose every minute or so, and Lysander was busily tapping his fingers on the window, beating out the measures of a new concerto. The morning was brilliant, the rich white-gold light of Lombardy rolling over the landscape, gilding the scene in the style of a Renaissance masterpiece. Even the smallest detail seemed touched with magic. The humblest peasant on the road was magnificent, a gift to commit to memory and treasure on a bleak grey day in England. I sighed, wishing Italy had seen fit to give us a kinder farewell. It would have been easier to leave her in a rainstorm.

Milan at least blunted the edge of my regret. The railway station was thronged with people speaking dozens of dialects in four languages, and I knew I would not miss the chaos of Italian cities. There was something to be said for the orderliness of English society, I reflected, looking for the fourth time to the station clock. Alessandro had scant minutes to find us, I realised. I scanned the crowd anxiously for his tall, elegant figure.

“Perhaps he’s been run over by a carriage,” Morag put in helpfully. I fished in my reticule and extracted her ticket.

“Board the train, Morag. Your seat is in third class. I will see you in Paris.”

She took the ticket, muttering in Gaelic under her breath. I pretended not to hear her and turned away, just in time to see Alessandro approaching. He was hurrying, as much as Alessandro ever hurried anywhere. His clothes were perfectly ordered, but his hair was slightly tumbled, and when he spoke his voice was faintly breathless.

“Ah! I have found you at last.” He greeted my brothers and Violante, who wailed louder and waved her handkerchief at him.

“Come along, Alessandro,” I told him. “We’ve only a moment or so to board.”

“Then let us embark,” he said, bowing from the neck. He offered his arm, and I noticed his other was carefully holding a basket covered with a damask cloth. Luncheon, I thought happily.

We were seated quickly in a surprisingly comfortable compartment. Violante and Lysander had begun an argument and were quietly hissing at one another. Plum took out his sketchbook to record a face he had seen on the platform. Only Alessandro seemed excited by the journey, his dark eyes flashing as they met mine.

“I have brought you a gift, a souvenir of my country,” he said softly, placing the basket on my knees. I stared at it.

“I had thought it was luncheon, but as the basket has just moved on its own, I rather hope it isn’t,” I told him.

He laughed, a courteously modulated sound. Florentines, I had observed, loved to laugh but only modestly.

At his urging I lifted the damask cloth and peered into the basket.

“How very unexpected,” I murmured. “And how kind of you, Alessandro. I don’t suppose you would mind telling me what it is, exactly?”

This time he laughed fully, throwing back his head and revealing a delightful dimple in his cheek. “Ah, Lady Julia, always you enchant me. It is a dog, what you call in your country an Italian greyhound. Surely you recognise her. Her breed has been painted for centuries.”

I peered again at the trembling creature nestled against a cushion. She was black and white, large patches, with a wet black nose and eyes like two bits of polished Whitby jet. She lifted her nose out of the basket and sniffed me deeply, then sighed and laid her head back onto her paws.

“Of course. I see the resemblance now,” I told him, wondering how this frail, ratlike creature could possibly be related to the cosseted pets I had seen gracing the laps of principesse in gilded frames.

“È ammalata,” Alessandro said apologetically. “She is a little unwell. She does not like the travelling. I put her yesterday into her little basket, and she does not like to come out.”

“Oh, that is quite all right,” I said, hastily pulling the damask over her nose. “Perhaps she just needs a bit of rest. What is she called?”

“That is for you to decide.”

I did not hesitate. “Then I shall call her after my favorite place in all of Italy. I shall call her Florence.”

Alessandro smiled, a smile a nymph would envy, beautiful curved lips and even white teeth. “You pay the greatest honour to my city, my Firenze. I am glad that you like her. I wanted you to have some token of my appreciation for this kind invitation to your family’s home.”

Strictly speaking, the invitation had been Plum’s and I noticed that there was no shivering, pointy-faced puppy for him. And as I clutched the basket and looked out of the window, saying my silent farewells to this country I had grown to love so well, I wondered what significance this present carried with it. Alessandro had implied it was a sort of hospitality gift, a way of thanking one’s hosts for opening their home. Still, I could not help but think there was something more pointed in his intentions. And I was not entirely displeased.

Paris was grey and gloomy, sulking under lowering skies like a petulant schoolgirl. We had tarried a few days to shop and show Alessandro the sights, but none of us forgot for long we were being called home in disgrace. Lysander and Violante had made up their quarrel and spent most of their time cooing and making revoltingly sweet faces at one another. Plum, doubtless irritated at their good humour, sulked until I bought him the most outrageously ugly waistcoat I could find—violet taffeta splashed with orange poppies. He insisted upon wearing it with his fez, and wherever we went, Parisians simply stopped and stared. For his part, Alessandro was subdued. I had thought the glories of Paris would enchant him, but he merely regarded them and made notes in his guidebook. It was not until I found him murmuring Italian endearments to Florence that I realised the poor boy must be homesick. He had never left Italy before, and this trip had been a sudden, wrenching thing. There had been no pleasurable time of anticipation, no peaceful evenings by the fire with maps and guidebooks and lists at hand, no chance to dream of it. I think the reality of the cold grey monuments and the wet streets dampened his spirits as thoroughly as they dampened our hems. I promised myself that he would enjoy Bellmont Abbey and our proper English Christmas, even if it killed me. Of course, I had no way of knowing then that it would indeed kill someone else.

As a contrast to the dripping skies of Paris, London was lit with sunset when we arrived, the great gold light burnishing the dome of St. Paul’s and lending a kindly glow to the chimney pots and brick houses stacked against each other like so many books in a shop. Even the air smelled sweeter to me here, a sure sign of my besotted state, for London’s air has never been salubrious. I pointed out the important landmarks to Alessandro, promising him we would return after Christmas for a thorough tour. He sat forward in his seat, eagerly pressing his hands to the window, taking in the great city.

“It is so big,” he said softly. “I never thought to see a city so large.”

“Yes, it is. And filthy besides, but I love it dearly. Now, we will make our way to the Grand Hotel for the night, and tomorrow we will embark for Blessingstoke. The train journey is not long. Blessingstoke is in Sussex, and the Abbey is quite near to the village proper.”

Plum leaned across Alessandro to take in the view. “God’s teeth, it hasn’t changed a bit.”

“Plum, it may be Shakespearean, but it is still an oath. You know how Aunt Hermia feels about profanity.”

He waved me off with a charcoal-smudged hand. “Auntie Hermia will be so happy to see her prodigal boys, she won’t care if I come draped in rags and swearing like a sailor. I’ll wager the fatted calf is being roasted as we speak.”

On that point I was forced to agree. Our Aunt Hermia, Father’s youngest sister, had come to live at the Abbey when our mother died from exhaustion. Ten children in sixteen years had been too much for her slight, graceful shape. Aunt Hermia had done her best to instill proper manners and a sense of decorum, but seven hundred years of March eccentricity was too much, even for her iron will. We were civilized, but the veneer was a thin one. In her later years, Aunt Hermia had even come to embrace her own peculiarities, and it was true that her drawing room was the only room in England where ladies were invited to smoke after dinner. Needless to say, Marches were seldom invited to Court.

“Speaking of returning home,” Plum said, his expression a trifle pained, “I don’t suppose we could stay at March House instead of the Grand Hotel?”

I blinked at him. “Plum, the arrangements have already been made at the hotel. I hardly think it would be fair to disappoint their expectations. Besides, Father is in Sussex. The house would have been closed up months ago, and I am certainly not going to simply turn up and expect the staff to scurry around, yanking off dust sheets and preparing meals with no warning.”

“They are servants, Julia,” Plum pointed out with a touch of exasperation. “They will be perfectly content to do whatever is expected of them.”

I looked at him closely, scrutinising his garments. His coat buttons were loose, a sure sign he had been tugging at them in distraction. It was a nervous habit from boyhood. He dropped buttons in his wake as a May Queen dropped flowers. The maids had long since given up stitching them back on, and he usually went about with his coat flapping loosely around him. Yes, something was clearly troubling him, and I did not think that it was solely his irritation at Lysander’s marriage. I suspected his pockets were thin—Plum’s tastes were expensive, and even Father’s liberal allowances only stretched so far.

Still, even if Plum was flirting with insolvency, there were other considerations. “It is impolite, both to the staff of March House, and the hotel,” I told him. “Besides, I hardly think that it will help our cause with Father to have descended on March House with no warning and inconvenienced his staff and eaten his food. You know they will send the bills to him. Under other circumstances, I might well agree with you, but I think a little prudence on our part might go some distance toward smoothing matters for Ly,” I finished.

Plum darted a look to the other part of the compartment where Lysander and Violante were huddled together, heads nearly touching as they whispered endearments.

“And we must do whatever we can for Lysander,” Plum added, his handsome mouth curved into a mocking smile. He left as quickly as he had come, settling himself some distance away behind a newspaper. I turned with an apologetic glance to Alessandro, but he was staring out the window, his expression deeply troubled and far away. I did not interrupt him, and the rest of the journey into London was accomplished in silence.

The manager of the Grand Hotel, in an act of unprecedented kindness, assigned me a suite on a different floor from my family. There had been some difficulty with the arrangements, he said, fluttering his hands in apology, our letter had come so late, it was such a busy season with the holiday fast approaching. I reassured him and took the key, grateful for the distance from the rest of the party. Violante and Lysander had broken out in a quarrel again on the station platform, Plum was sulking openly, and Alessandro was by now visibly distressed. He only smiled when he noticed my trouble in coaxing Florence from her basket. She remained curled on her cushion, staring at me with the lofty disdain of a Russian czarina.

“Florence, come out at once. This is unacceptable,” I told her. Alessandro smiled at me, a smile that did not touch the sadness in his eyes.

“Ah, my dear lady. She does not understand you. She is an Italian dog, you must speak Italian to her.”

I stared at him, but there was no sign of jocularity in him. “You are not joking? I must speak Italian to her?”

“But of course, my lady. Do as I do.” He bent swiftly and pitched his voice low and seductive. “Dai, Firenze.”

The little dog leaped up at once and waited patiently at his heel. “You see? Very easy. She wants to please you.”

The dog and I regarded each other. I had my doubts that she wished to please me, but I thanked Alessandro just the same and turned to make my way into the hotel. Florence sat, staring down her long nose at me.

I sighed. “Andiamo, Firenze. Come along.” She trotted up and gave my skirt hem a deep sniff. Then she gave a deep, disappointed sigh.

“I know precisely how you feel.”

The next morning I made my way down to breakfast in the hotel’s elegant dining room, feeling buoyant with good cheer and a good night’s sleep. Something about being on English soil again had soothed me, and I had slept deeply and dreamlessly, waking only when Florence barked out an order to be taken for a walk. I handed her off to a grumbling Morag with a few simple words of Italian, although I had little doubt Morag would simply bark back at her in Gaelic. But even Morag’s sullenness was no match for my cheerful mood as I entered the dining room. I might have known that it would not last.

Resting against my plate was a hastily scrawled note from Lysander explaining that he and Violante had chosen to have a lie-in and would take the later conveyance instead of the morning train as we had planned. I wrinkled my nose at the note and crumpled it into my butter dish. A lie-in indeed. More like an attack of the cowardy-cowardy custards. Ly was nervous at the prospect of facing Father. The possibility of losing his considerable allowance, particularly with a wife to maintain, was a grim one. The notion of keeping Violante on the proceeds of his musical compositions was laughable, but also frighteningly real. Ly was simply playing for time, expecting the rest of us to journey down to Bellmont Abbey and smooth the way for him, soothing Father out of his black mood and making him amenable to meeting Lysander under happier terms.

It simply would not do. I applied myself to a hearty breakfast of eggs, bacon, porridge, toast, stewed fruit, and a very nice pot of tea. I enjoyed it thoroughly. The Italians, for all their vaunted cookery skills, cannot do a proper breakfast. A bit of bread and a cup of milky coffee is a parsimonious way to begin one’s day. When I was well fortified, I had a quick word with the waiter and made my way to Lysander and Violante’s rooms and tapped sharply on the door.

There was a sleepy mumble from within, but I simply rapped again, more loudly this time, and after a long moment, Lysander answered the door, wrapping a dressing gown around himself, his expression thunderous.

“Julia, what the devil do you want? Did you not get my note?”

I smiled at him sweetly. “I did, in fact. And I am afraid it will not serve, Lysander. We must be at the train station in a little more than an hour. I have ordered your breakfast to be sent up. I am afraid there will not be time for you to have more than rolls and coffee, but the hotel is packing a hamper for the train.”

He gaped at me. “Julia, really. I do not see why—”

Violante appeared then, clutching a lacy garment about her shoulders and yawning broadly, her black hair plaited in ribbons like a schoolgirl’s. She looked pale and tired, plum-purple crescents shadowing her eyes. I greeted her cordially.

“Good morning, Violante. I do hope you slept well. There has been a slight change in plans, my dear. We are all travelling down together this morning. Morag will help you dress. She is quite efficient, for all her sins, and the hotel maids are dreadfully slow.”

“Si, Giulia. Grazie.” She nodded obediently, but Lysander stood his ground, squaring his shoulders.

“Now, see here, Julia. I will not be organised by you as though I were a child and you were my nanny. I am your brother, your elder brother, a fact I think you have rather forgotten. Now, my wife and I will travel down to Blessingstoke when it suits us, not when you command.”

I stared at him, eyebrows slightly raised, saying nothing. After a moment he groaned, his shoulders drooping in defeat.

“Why, why am I plagued by bossy women?”

I smiled at him to show that I bore no grudge. “I am sure I could not say, Lysander. I will see you shortly.”

I turned to Violante who had watched our exchange speculatively. “Remind me to have a little chat with you when we reach the Abbey, my dear.”

She opened her mouth to reply, but Lysander pulled her back into their room and banged the door closed. I shrugged and turned on my heel to find Plum lingering in his doorway, doing his best to smother a laugh. I fixed him with a warning look and he raised his hands.

“I am already dressed and the hotel’s valet is packing my portmanteau as we speak. I was just going downstairs for some breakfast.”

I gave him a cordial nod and proceeded to my suite, feeling rather pleased with myself. An hour later the feeling had faded. Despite my best efforts, it had taken every spare minute and quite a few members of the hotel staff to ensure the Marches were ready to depart. Alessandro was ready, neatly attired and waiting patiently at the appointed hour, but two valets, three maids, and Morag were required to pack the others’ trunks and train cases. A Wellington boot, Violante’s prayer book and Plum’s favourite coat—a revolting puce affair trimmed with coffee lace—had all gone missing and had to be located before we could leave. I had considered bribing the valet not to find Plum’s coat, but it seemed unkind, so I left well enough alone. In the end, four umbrellas, two travelling rugs, and a strap of books could not be stuffed into the cases. We made our way to the carriages trailing maids, sweet wrappers, and newspapers in our wake. I am not entirely certain, but I think I saw the hotel manager give a heartfelt sigh of relief when our party pulled away from the kerb.

Traffic, as is so often the case in London, was dreadful. We arrived at the station with mere minutes to spare. A fleet of porters navigated us swiftly to the platform, grumbling good-naturedly about the strain on their backs. I had just turned to answer the sauciest of them when I heard my name called above the din of the crowded platform.

“Julia Grey! What on earth do you mean loading down honest Englishmen like native bearers? Have you no shame?”

I swung round to see my favourite sister bearing down on me with a porter staggering behind her. He was gasping, his complexion very nearly the colour of Plum’s disgusting coat.

“Portia!” I embraced her, blinking hard against a sudden rush of emotion. “Whatever are you doing here?”

“I am travelling down to the Abbey, same as you. I had not planned to go down for another week or two, but Father is rather desperate. He has a houseful of guests already and no one to play hostess.”

“Christmas is almost a month away. Why does he have guests already? And what of Aunt Hermia? We had a letter from her.”

Portia shook her head. “Father is up to some mischief. There are surprises in store for us, that is all I have been told. As for Auntie Hermia, she is here in London. She came up to have a tooth pulled, and is still too uncomfortable to travel. Jane is looking after her until she feels well enough, then they will come down together. In the meantime, Father sent for me. You know the poor old dear is hopeless when it comes to place cards and menus.”

She cast a glance over my shoulder. “Ah, I see Ly is here after all. I wagered Jane five pounds he would hide out until someone else softened Father up for him. Hullo, Plum! I did not see you there, skulking behind Julia. Come and give me a kiss. I have rather missed you, you know.”

Plum came forward and kissed her affectionately. They had always been great friends and partners in terrible escapades, though they had not seen much of one another in recent years. Plum had travelled too much, and was faintly disapproving of Portia’s lifestyle. For her part, Portia had embraced a flamboyant widowhood. She habitually dressed in a single colour from head to toe, and her establishment included a lover—her late husband’s cousin as it were. His female cousin, much to the shock of society.

Today she was dressed all in green, a luscious colour with her eyes, but her beloved Jane was not in evidence. Plum kissed her soundly on the cheek.

“That’s better,” she said, releasing Plum from a smothering embrace. “How do you like Lysander’s bride? She’s a pretty little thing, but I fancy she keeps him on his toes. She is a Latin, after all. And who is this?” she asked, fixing her gaze on Alessandro. He had been standing a small, tactful distance apart, but he obeyed Portia’s crooked finger, doffing his hat and sweeping her as elegant a bow as the crowded platform would permit.

“Alessandro Fornacci. Your servant, my lady.”

Portia regarded him with unmitigated delight, and I could see her mouth opening—to say something wildly inappropriate, I had no doubt. I hurried to divert her.

“Alessandro, this is our sister, Lady Bettiscombe. Portia, my darling, I think we must board now before the train departs without us. The station master looks very cross indeed.”

I looped my arm through hers and she permitted me to steer her onto the train. She said nothing, asked no questions, which made me nervous. A quiet Portia was a dangerous Portia, and it was not until we were comfortably seated and the train had eased out of the station that I permitted myself to relax a little. Alessandro and Plum had taken seats a little distance apart, and Lysander and Violante, after exchanging hasty greetings with Portia had moved even farther away. Lysander was still sulking over his enforced departure, and Violante was too indolent to care where they sat. A foul smell emanated from the basket at Portia’s feet, and I sighed, burying my nose in my handkerchief. If I sniffed very deeply, I could almost forget the odor.

“I cannot believe you brought that monstrosity,” I told her.

Portia gave me a severe look. “You are very cold toward Mr. Pugglesworth, Julia, and I cannot think why. Puggy loves you.”

“Puggy loves no one but you, besides which he is half decayed.”

“He is distinguished,” she corrected. “Besides, I note that you have a similar basket. Have you acquired a souvenir on your travels?”

“Yes. A creature almost as vile as Puggy. She is temperamental and hateful and she loathes me. Yesterday she gnawed the heel from my favorite boot simply because she could.” I nudged her basket with my toe and she snarled in response. “She only understands Italian, so I am trying to teach her English. Quiet, Florence. Tranquillamente.”

“What on earth possessed you to buy her if you hate her so much?” Portia demanded, peering through the wickets of the basket. “All I can see are two eyes that seem to be glowing red. I should be very frightened if I were you, Julia. Sleep with one eye open.”

“I did not buy her,” I told her softly. “She was a gift.”

Portia’s eyes flew to Alessandro’s dark, silken head, thrown back as he laughed at some remark of Plum’s. “Ah. From the enchanting young man. I understand. Tell me, how old is he?”

“Twenty-five.”

She nodded. “Perfect. I could not have chosen better for you myself.”

I set my mouth primly. “I do not know what you are talking about. Alessandro is a friend. The boys have known him for ages. He wanted to see England, and Lysander is too much of a custard to face Father without some distraction. That is all.”

“Indeed?” Portia tipped her head to the side, studying my face. “You know, dearest, even under that delicious veil, I can see your blushes. You have gone quite pink about the nose and ears, like a rabbit. I think that boy likes you. And what’s more, I think you like him, too.”

“Then you are a very silly woman and there is nothing else to say. It is overwarm in here. That is all.”

Portia smiled and patted my arm. “If you say so, my love. If you say so. Now, what news have you had of Brisbane? I saw him last month and I know he has been a frequent guest at Father’s Shakespearean society of late, but I haven’t any recent news of him.”

“You saw him last month?” I picked at the stitching on my glove, careful to keep my voice neutral. “Then you know more of him than I. How did he seem?”

“Very fond of the Oysters Daphne,” she said, her eyes bright with mischief. “He made me send along the receipt for his housekeeper. Julia, mind what you’re doing. You’ve jerked so hard at that thread, you’ve torn the fur right off the cuff.”

I swore under my breath and tucked the ragged edge of the fur into my glove. “You mean you had him to dinner? At your house?”

“Where else would I entertain a friend? Honestly, Julia.”

“Did you dine alone?”

Portia rolled her eyes. “Don’t be feeble. Of course not. Jane was there, and Valerius as well,” she said. I relaxed a little. Valerius was our youngest brother and a passionate student of medicine. His favourite pastime was telling gruesome tales at the dinner table, not exactly an inducement to romance.

Portia poked me suddenly. “You little green-eyed monster,” she whispered. “You’re jealous!”

“Well, of course I am,” I said, sliding my gaze away from hers. “I adore your cook’s Oysters Daphne. I am sorry to have missed them.”

She snorted. “Oh, this has less to do with oysters than with the haunch of a handsome man.” She started laughing then, great cackling peals of laughter. I reached out and twisted a lock of her hair around my finger and jerked sharply.

“Leave it be, Portia.”

She yanked her hair out of my grip and edged aside, a wicked smile still playing about her mouth. “You daft girl, you cannot possibly imagine I want him for myself.”

I shrugged and said nothing.

“Or that he wants me,” she persisted. Still I said nothing. “Oh, I give up. Very well, think what you like. Go on and torture yourself since you seem to enjoy it so. But tell me this, have you had a letter from him since you went away?”

I looked out of the window, staring at the houses whose back gardens ran down to the rail line. “How curious. Someone has pegged out their washing. See the petticoats there? She ought to have hung them inside by the fire. They’ll never dry in this weather.”

Portia pinched my arm. “Avoidance is a coward’s tactic. Tell me all.”

I turned back to her and lifted the veil of my travelling costume, tucking it atop my hat. “Nothing. I know nothing because he has not written. Not a word in five months.”

My sister pursed her lips. “Not a word? Even after he kissed you? That is a shabby way to use a person.”

I waved a hand. “It is all water down the stream now. I have done with him. I doubt I shall meet him again in any case. Our paths are not likely to cross. We have no need of an inquiry agent, and the only relation of his who moves in society is the Duke of Aberdour. And Brisbane has little enough liking for his great-uncle’s company.”

“True enough, I suppose.”

I looked at her closely. “Do not think on it, Portia. It was foolish of me to imagine there was something there. I want only to put it behind me now.”

Portia smiled, a smile that did not touch her eyes. She was speculating. “Of course, my love,” she said finally. “Now I am more convinced than ever that you did a very wise thing.”

“When?”

Portia nodded toward Alessandro. “When you decided to bring home that most delightful souvenir.”

I slapped lightly at her arm. “Stop that at once. He will hear you.”

She shrugged. “And what if he does? I told you before, a lover is precisely the tonic you need. Julia, I was gravely worried about you when you left England. You were ailing after the fire, and I believed very strongly that it was possible you might not ever recover—not physically, but from the trauma your spirit had suffered. You learned some awful truths during that investigation, truths no woman should ever have to learn.” She paused and put a hand over mine. “But you did recover. You are blooming again. You were a sack of bones when you left and pale as new milk. But now—” she ran her eyes over my figure “—now you are buxom and bonny, as the lads like to say. You have your colour back, and your spirit. So, I say, complete the cure, and make that luscious young man your lover.”

I laughed in spite of myself. “I am five years his elder.”

“And very nearly a virgin in spite of your marriage,” she retorted. I poked a finger hard into her ribs and she collapsed again into peals of merry laughter.

“Good God, what are the two of you on about?” Plum demanded from across the compartment.

Portia sobered slightly. “We were wondering what Father has bought us for Christmas.”

Plum regarded her gloomily. “Stockings of coal and switches, I’ll warrant.”

Portia shot me an impish look. “Well, perhaps there will be other goodies to open instead.”

This time I did not bother to pinch her. I merely opened my book and pretended to read.