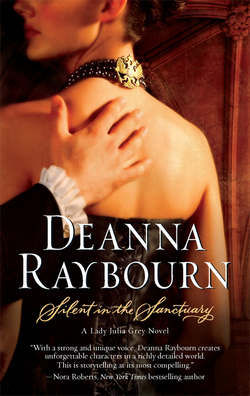

Читать книгу Silent in the Sanctuary - Deanna Raybourn, Deanna Raybourn - Страница 8

ОглавлениеTHE FOURTH CHAPTER

Mischief, thou art afoot, Take thou what course thou wilt. —JULIUS CAESAR

I stood motionless for a lifetime it seemed, although I know it cannot have been more than a few seconds. I summoned a deliberate smile and extended my hand, forcing my voice to lightness. Rather unexpectedly, both were steady.

“Brisbane, what a surprise to see you. Welcome to Bellmont Abbey.”

He shook my hand as briefly as courtesy would permit, bowing from the neck, his face coolly impassive as Plum’s beloved Carrara marble. He was exquisitely dressed in evening clothes even Ly would approve, all black-and-white elegance, down to the silken sling that held his left arm immobile just above his waist.

“My lady. Welcome home from your travels.”

My smile was polite, wintry, nothing more. Any observer might have thought us the most casual of acquaintances. But I was deeply conscious of Father and Portia watching us intently.

“Thank you. Did I understand Father correctly? Are congratulations in order?”

“The elevation is a very recent one. In fact the letters patent have not yet been read. His lordship is overhasty in his compliments,” he said mildly, but I knew him well enough to know this was no façade of modesty. Brisbane himself would not care about titles, and I could only imagine he would accept one because it ensured his entrée into the highest circles of society—a useful privilege for someone in his profession.

For my part, I was impressed in spite of myself. I was one of the few people who knew the truth of Brisbane’s parentage and upbringing. To rise from that to a viscountcy was little more than miraculous. It meant whilst I had been sunning myself in Italy, Brisbane had busied himself investigating something very delicate and probably very nasty for someone very highly placed.

“I did not realise you were staying at the Abbey, my lord. I confess I am surprised to see you here.”

Brisbane’s eyes flickered toward my father. “I might say the same of you, my lady. His lordship declined to mention you were expected to return home before next summer.”

Father’s eyes were open very wide, a sure sign he had been up to mischief. He was incapable of feigning innocence. I looked from him to Brisbane, fitting the pieces together swiftly. My appearance was as much of a surprise to Brisbane as his was to me. He was pale under the olive of his complexion, and I realised he was attempting to compose himself. Whatever he had expected of his visit to Bellmont Abbey, a reunion with me was no part of it.

I had just opened my mouth to tease him when he looked past me and beckoned sharply to a lady hesitating shyly on the edge of our circle. I had not noticed her before, but now I wondered how that was possible.

“My lady,” Brisbane said smoothly, “I should like to present to you my fiancée, Mrs. King. Charlotte, Lady Julia Grey.”

I know that I put out my hand, and that she took it, because I looked down to see my fingers grasped warmly in hers, but I felt nothing. I had gone quite numb as I took in the implication of what Brisbane had just said.

“Mrs. King,” I murmured. Recovering myself quickly, I fixed a smile on my lips and repeated the greeting I had given Brisbane. “Welcome to the Abbey.”

“And welcome back to England, my lady,” she said breathlessly.

She was a truly lovely creature, all chocolate-box sweetness with a round, dimpled face and luscious colouring. She had clouds of hair the same honeyed red-blond I had admired on a Titian Madonna. Her eyes were wide and almost indescribably blue. She had a plump, rosebud mouth and an adorably tiny nose unadorned by even a single freckle. Only the chin, small and pointed like a cat’s, belied the sweetness of her expression. There was firmness there, perhaps even stubbornness, although now she was smiling at me in mute invitation to befriend her. Unlike me, she wore widow’s weeds, although touches of purple indicated her loss was not a recent one. The black suited her though, highlighting a certain fragile delicacy of complexion no cosmetic could ever hope to simulate. She was a Fragonard milkmaid, a Botticelli nymph. I hated her instantly.

“I am so very pleased to make your acquaintance, my lady,” she was saying. “Lord Wargrave has told me simply everything about you. I know we are going to be very great friends.” She was earnest as a puppy, and I had little doubt most people found her charming.

“Has he indeed? How very kind you are,” I said, fingering the pendant at my throat. It had been an involuntary action, and I realised as soon as my fingers touched the cool silver it was a mistake. Mrs. King’s bright blue gaze fixed on the piece at once.

“What an unusual pendant. Did you acquire it on your travels?” she asked, peering closely at the coin.

“No. It was a gift,” I said, covering its face with a finger. I turned to Brisbane, who was watching our exchange closely. I nodded toward the sling. “I see you have managed to injure yourself, my lord. Nothing serious, I hope.”

He lifted a brow. “Not at all. A nasty spill from a horse a fortnight ago, nothing more. His lordship was kind enough to invite me to recuperate here away from the bustle of the city.”

“And you will be here for Christmas as well?” I asked, forcing my tone to brightness.

“As will my fiancée,” he replied coolly, locking those witch-black eyes onto mine.

I did not blink. “Excellent. I shall look forward to getting to know her intimately.” The words were blandly spoken, but Brisbane knew me well enough to hear the threat implicit within them.

His gaze wavered slightly, and I inclined my head. “I do hope you will excuse me. I must greet the other guests. Mrs. King, a pleasure,” I said, withdrawing from the group. Father caught my eye, his own eyes bright with mischief. I turned my head, not sur prised to find Portia at my elbow.

“Well done, dearest,” she whispered.

“Whiskey,” I hissed. “Now.”

In another of the little altar alcoves a sideboard had been arranged with spirits of every variety. We made our way to the whiskey decanter and stood with our backs to the room. Portia poured out a generous measure for both of us and we each took a healthy, choking sip. I swallowed hard and fixed her with an Inquisitor’s stare.

“I shall only ask you once. Did you know?”

She paled, then took another sip of her whiskey, colour flooding her cheeks instantly. “Of course not. I knew Father meant to invite him down for Christmas. I thought it might be a nice surprise for you. But I had no idea he was being elevated, nor that he had that…that creature with him. How could he?”

Portia shot Brisbane a dark look over her shoulder. “He kissed you. He gave you that pendant. I thought that meant something.”

“Then you are as daft as I. Drink up. We cannot hover over the spirits all evening. We must mingle with the other guests.”

She stared at me as though I had lost my senses. “But are you not—”

“Of course, dearest. I am entirely shattered. Now finish your whiskey. I see Aunt Dorcas mouldering in an armchair by the fire and I must say hello to her before she decays completely.”

Portia’s eyes narrowed. “You are not shattered. You are smiling. What are you about?”

“Nothing,” I told her firmly. “But I have my pride. And as you pointed out,” I said with a nod toward Alessandro, “I have alternatives.”

Alessandro smiled back at me, shyly, his colour rising a little.

Portia poked me. “What are you thinking?”

I put our glasses on the table and looped my arm through hers, pulling her toward Aunt Dorcas.

“I was simply thinking what a delight it will be to introduce Alessandro to Brisbane.”

Aunt Dorcas had established herself in the armchair nearest the fire, and it looked as though it would take all of the Queen’s army to roust her out of it. No one would call her plump, for plumpness implies something jolly or pleasant, and Aunt Dorcas was neither of those. She was solid, with a sense of permanence about her, as though she had always existed and meant to go on doing so forever. Disturbingly for a woman of her size and age, she had a penchant for girlish ruffles and bows. She was draped in endless layers of pink silk and wrapped in an assortment of lace shawls, with lace mitts on her hands and an enormous lace cap atop her thinning hair. She wore only pearls, yards of them, dripping from her décolletage and drawing the eye to her wrinkled skin. She had gone yellow with age, like vellum, and every bit of her was the colour of stained ivory—teeth, hair, skin, and the long nails that tapped out a tuneless melody on the arm of her chair. But her eyesight was sharp, and her hearing even better. She was talking to, or rather at, Hortense de Bellefleur, Father’s particular friend. Hortense was stitching placidly at a bit of luscious violet silk. She was dressed with a Frenchwoman’s natural elegance in a simple gown of biscuit silk, an excellent choice for a lady of her years. She looked up as we approached, smiling a welcome. Aunt Dorcas simply raised her cane to poke my stomach.

“Stop there. I don’t need you breathing all over me. Where have you been, Julia Grey? Gallivanting about Europe with all those filthy Continentals?”

Her voice carried, and I darted a quick glance at Hortense, but she seemed entirely unperturbed. Then again, very little ever perturbed Hortense.

“Xenophobic as ever, I see, Aunt Dorcas,” I said brightly.

“Eh? Well, never mind. You’ve put on a bit of weight you have, and lost that scrawny look. You were a most unpromising child, but you have turned out better than I would have thought.”

The praise was grudging, but extremely complimentary coming from Aunt Dorcas. She turned to Hortense.

“Julia was always plain, not like Portia there. Portia has always been the one to turn men’s heads, haven’t you, poppet?”

“And some ladies’,” I murmured. Portia smothered a cough, her shoulders shaking with laughter.

“Yes, Aunt Dorcas, but you must agree Julia is quite the beauty now,” my sister put in loyally.

“She will do,” Aunt Dorcas said, a trifle unwillingly, I thought.

I bent swiftly to kiss Hortense’s cheek. “Welcome home, chérie,” she whispered. “It is good to see you.”

Simple words, but they had the whole world in them, and I squeezed her shoulder affectionately. “And you.”

“Come to my boudoir tomorrow. We will have a pot of chocolate and you will tell me everything,” she said softly, with a knowing wink toward Alessandro.

Before I could reply, Aunt Dorcas poked me again with her cane. “You are too close.”

I obeyed, moving to stand near Portia. “Portia tells me you have been staying here. I hope you find it comfortable.”

Aunt Dorcas puffed out her lips in a gesture of disgust. “This old barn? It is draughty, and I suspect haunted besides. All the same, I think it very mean of Hector not to invite me more often. I am family after all.”

I thought of poor Father, forced to face the old horror for months on end, and I hurried to dissuade her. “You would be terribly bored here. Father spends all his time in his study, working on papers for the Shakespearean Society.”

“The Abbey is indeed draughty,” Portia put in quickly. “And we do have ghosts. At least seven. Most of them monks, you know. I shouldn’t be surprised if one walked abroad tonight, what with all of the excitement of the house party. They get very agitated with new people about. Do let us know if you see a holy brother robed in white.”

Portia’s expression was deadly earnest and it was all I could do not to burst out laughing. But Aunt Dorcas was perfectly serious.

“Then we must have a séance. I shall organise one myself. I have some experience as a medium, you know. I have most considerable gifts of a psychic nature.”

“I have no doubt,” I told her, shooting Portia a meaningful look.

Portia put an arm about my waist. “Aunt Dorcas, it has been lovely seeing you, but I simply must tear Julia away. She hasn’t spoken to half the room yet, and I am worried she might give offense.”

Aunt Dorcas waved one of her lace scarves at us, shooing us away, and I threw Hortense an apologetic glance over my shoulder.

“I do feel sorry for dear Hortense. However did she get landed with the old monstrosity?”

Portia shrugged. “We have suffered with Aunt Dorcas for the whole of our lives. Hortense is fresh blood. Let her have a turn. Ah, here is someone who is anxious to see you.”

She directed me toward a small knot of guests gathered around a globe, two ladies and two gentlemen. As we drew near, one of the ladies spun round and shrieked.

“Julia!” She threw her arms about me, embracing me soundly.

I patted her shoulder awkwardly. “Hello, Lucy. How lovely to see you.” She drew back, but kept my hands firmly in her own.

“Oh, I am so pleased you have arrived. I’ve been fairly bursting to tell you my news!”

“Dear me, for the carpet’s sake, I hope not. What news, my dear?”

She tittered at the joke and gave me a playful slap.

“Oh, you always were so silly! I am to be married. Here, at the Abbey. In less than a week. What do you make of that?”

She was fairly vibrating with excitement, and I realised I was actually rather pleased to see her. Lucy was one of the most conventional of my relations, a welcome breath of normality in a family notorious for its eccentricity. To my knowledge, Lucy was one of the few members of our family never to have been written up in the newspapers for some scandal or other. We exchanged occasional holiday letters, nothing more. I had not seen her in years, but I was astonished at how little she had changed. Her hair was still the same rich red, the colour of winter apples, and springing with life. And her expression, one of perpetual good humour, was unaltered.

“My heartiest good wishes,” I told her. I glanced behind her to where the other lady stood, a quiet figure, her poise all the more noticeable against Lucy’s ebullience.

“Emma!” I said, moving forward to embrace her. “I am happy to see you.”

Emma was wearing a particularly trying shade of green that did nothing for her soft, doe-brown eyes, her one good feature. Her hair was unfashionably red, like Lucy’s, but where Lucy’s was curly and vibrant with colour, Emma’s was straight and so dull as to be almost brown. She wore it in a severe plait that she wound about her head, pinned tightly. Her face was unremarkable; her features would have suited the muslin wimple of a cloistered sister. But she smiled at me, a warm, genuine smile, and for a moment I forgot her plainness.

“Julia, you must tell us all about your travels. We have just been discussing Lucy’s wedding trip,” she told me, motioning with one small, lily-white hand toward the globe. Flanking it were the two gentlemen, one the elder by some two decades, and clearly the other’s superior in rank and wealth. His evening clothes were expensively made and the jewel in his cravat was an impressive sapphire. Lucy went to him and put her arm shyly in his.

“Julia, I should like to present my fiancé, Sir Cedric Eastley.”

If I was startled, I endeavoured not to show it. Had I been asked to choose, I would have picked the younger man for Lucy’s betrothed. He looked only a handful of years her elder, while Sir Cedric might well have been her father.

“Cedric, this is my cousin, Lady Julia Grey.”

He took the hand I offered, his manners carefully correct, although not from the schoolroom, I fancied. There was the slightest hesitation in his gestures, as though he were taking a fleeting second to remember a lesson he had only recently been taught. He performed flawlessly, but not naturally, and it occurred to me this was a man who had brought himself up in the world, by his own efforts, and his baronetcy had been his reward.

Lucy gestured toward the younger man, a tall, slightly built fellow with a pleasant expression and quite beautiful eyes.

“And this is Sir Cedric’s cousin and secretary, Henry Ludlow.”

Unlike Sir Cedric’s very new, very costly clothing, Ludlow’s attire spoke of genteel poverty, but excellent make. Clearly he had come down in the world to accept a post in his cousin’s employ, and I wondered at the vagaries of fate that had clearly elevated the one while casting the other down. I thought they should prove interesting guests and I turned to Lucy to inquire how long they would be with us at the Abbey.

“Until the new year,” she announced. “Cedric and I will be married here in the Abbey on Saturday by the vicar. Then we mean to stay through Christmas. It will be like the old times again, with all of the Marches together,” she said, her eyes glowing with excitement. It seemed needlessly cruel to point out that her surname was not March and that she had in fact never spent a Christmas at the Abbey. I suspected she and Emma had yearned to belong to our family in a way that an Easter fortnight each year could simply not accomplish. Perhaps being married among us and spending her first Christmas in our midst would assuage some of that childhood hunger.

“Emma mentioned a wedding trip,” I said, gesturing toward the globe. It was a sad affair, much mauled by us as children and by Crab, Father’s beloved mastiff. She had taken to carrying it around with her as a pup, and by the time Father had trained her not to do so, the globe was beyond salvation.

Sir Cedric pointed to Italy. “We were thinking of Florence. And perhaps Venice as well, with a bit of time spent by the Tyrrhenian Sea in the summer. I know the loveliest spot, just here, below this fang mark.”

I nodded. “Italy is a perfect choice. I understand the winters are not too brutal, and the scenery is quite breathtaking.” I said nothing of the people, but I made the mistake of catching Portia’s eye just as she was raising an eyebrow meaningfully toward Alessandro. I straightened at once.

Portia commandeered me again, excusing us from the little group and guiding me to where Violante and Lysander were standing with Alessandro. Violante was resplendent in a flame-coloured gown, her expression sedate. Father had given her a noticeably wide berth, and I wondered if he had spoken to her at all. I imagined he had given her a cursory welcome and then excused himself to speak with anyone else. To make up for his neglect, I addressed her with deliberate warmth.

“Violante, how lovely you look. That gown suits you. You look like sunset over the Mediterranean.”

She smiled, her slow, lazy smile. “Grazie, Giulia.” She waved her glass at me. “What am I drinking? It is very good.”

I looked at her glass and grimaced. “That is Aunt Dorcas’ frightful elderberry cordial. I am surprised at Aquinas pouring it for you before dinner.”

“Plum, he brought it. I tell him I want something English to drink. Lysander, he has the whiskey, but I am given this. It is very nice.”

Well, Plum might have found her something more suitable, but I was pleased he was making an effort to get on with Violante at all. “Mind you don’t drink too much of it,” I warned her. “It is an excellent cure for insomnia or incipient cold, but more than a tiny glass will bring on the sweats.”

She blinked at me. “Che cosa?”

I searched for the word, but Alessandro stepped in smoothly. “La suda,” he said softly. She looked at him a moment, then shrugged.

Portia elbowed me gently aside. “Alessandro, have you met my father yet?”

Alessandro shook his head. “I regret, no, my lady. His lordship has been very busy with his other guests.”

Even before she spoke the words aloud, I knew what she was about. “In that case, Julia, you must perform the introductions. I know Father must be simply perishing to meet your friend.”

I glanced over to where Father stood, still in conversation with Brisbane, then back to Portia. Her eyes were alight with mischief. Alessandro was regarding me with his customary Florentine dignity. “Ah, yes. I would very much like to pay my respects to his lordship, and thank him for his hospitality.”

“Of course,” I said faintly. “Portia, are you coming, dearest?”

“Oh, I thought I would get to know our delightful new sister-in-law,” she said, delivering the coup de grâce. “But do not let me keep you.”

“Come along, Alessandro,” I said through gritted teeth. He cupped my elbow in his hand, guiding me gently—a wholly pleasant sensation, but I was still annoyed. I should not have been the one to make the introductions. He had been Plum’s friend, and Ly’s as well, before he had been mine. It had been their inspiration to bring him to England, but now that Father had to be dealt with, they were perfectly content to let me brave the lion’s den on my own. Plum had made the acquaintance of Mrs. King and was busy giving her a tour of the room’s beauties, and Lysander was too consumed with his bride to have a thought for anyone else.

And Portia was determined to stir the pot with Brisbane. I noticed his eyes sharpening as we approached, nothing more. There was no raising of his expressive brows, no naked curiosity, only the intense watchfulness of a lion lazing in the shade by a pond where the gazelle will drink.

“Father,” I said, my voice a trifle thin, “I should like you to meet our friend, Alessandro. He came with us from Italy. Count Alessandro Fornacci. Alessandro, my father, Lord March.”

Father turned to greet Alessandro, welcoming him with more warmth than I would have imagined. Alessandro accepted his welcome with exquisite courtesy, expressing his rapture at being in England and his extreme pleasure in sharing this most English of holidays.

“Hmm, yes,” Father said, his eyes moving swiftly between us. Alessandro’s hand had lingered a moment too long at my elbow, and Father had not missed it. “Your room is satisfactory?”

I suppressed a sigh. Father would not have cared if Alessandro had been lodged in the dovecote with only a blanket to cover him and a stray cat for conversation. He meant to detain him, to take the measure of him, and perhaps to let Brisbane do so, as well.

“My room is very nice. It overlooks a maze, very lovely.”

“Excellent. You will want to see the maze up close, I’m sure. Mind you take a guide. Devilish tricky to get out of,” Father said, laughing heartily. I stared at him. Father was never jolly. He was putting on dreadfully for Alessandro, and I was just about to send manners to the devil and lead Alessandro away when Brisbane put out his hand.

“Nicholas Brisbane.”

Alessandro clasped his hand and bowed formally. “Mr. Brisbane.” Father gave a guffaw. “Not just Brisbane anymore. He’s a viscount any day now, my lad. Lord Wargrave.”

“Milord,” Alessandro amended.

Brisbane waved a careless hand. “No need to stand on ceremony. We are among friends here. Very good friends, I should think,” he finished with a flick of his gaze toward me.

“Quite,” I said sharply. “Ah, I see Uncle Fly and his curate have finally arrived. Come along, Alessandro. I should like to introduce you to my godfather.”

Before I could manage our escape, Father caught sight of Uncle Fly and bellowed out, “What kept you, Fly? Damned inconsiderate to make me wait for my dinner.”

Uncle Fly laughed and clapped a hand to Lucian Snow’s shoulder. “Blame the lad. He was an hour tying his cravat. Doubtless to impress the ladies.”

Father and Uncle Fly chuckled like schoolboys, and Lucian Snow smiled good-naturedly. “Well, with such lovely company a gentleman must trouble himself to look his best,” he said, sweeping the room with a gallant nod. A few ladies tittered, but I realised Portia was not among them. She had taken herself off, and I cursed her for a traitor that she had dropped me in it so neatly and then fled.

But I had no time to consider her whereabouts. Uncle Fly had made a beeline for me, Snow following in his wake. My godfather smothered me in an embrace that smelled of cherry brandy and something more—earth, no doubt. Uncle Fly was an inveterate gardener and spent most of his time puttering in his gardens and conservatory. No matter how often he scrubbed them, his hands were always marked with tiny lines dark with soil, like rivers on an ancient map. His fingertips were stained green, his lapels dusted with velvety yellow pollen. And his hair, tufts of fluffy white cotton that stood out about his head where he had tugged at it in distraction, was usually ornamented with a leaf or petal, and on one memorable occasion, a grasshopper.

His curate could not have cut a more opposite figure. He was taller than the diminutive Fly by half a foot, and more slender, although one would never think him slight. His posture was impeccable; he was straight as a lance, with a slight lift of the chin that made it seem as if he were gazing at some distant horizon. But when the introductions were made and he bowed over my hand, his eyes were fixed firmly on mine. They were warm, melting brown, like a spaniel’s, and they were merry. He twinkled at me like a practised rogue, and I found myself wondering how a man like him had come to hold the post of curate in an obscure country village. I introduced him to Alessandro, and Snow gamely attempted to greet him in Italian. It was laboured and wildly ungrammatical, but he laughed at his own mistakes, and Alessandro tactfully pretended not to notice.

Just then I saw Portia slip in, her expression smug. Before I could accost her, Aquinas entered and announced dinner. There was a bit of a scramble for partners, but since we were an odd number with more gentlemen than ladies, Portia insisted we dispense with etiquette and instructed each gentleman to choose the lady he wished to lead in.

To my surprise, Lucian Snow offered me his arm. “My lady, I hope you will do me the honour?”

I hesitated. Alessandro was hovering near, too polite to dispute with Snow, but a little dejected, I think. Just then Portia glided over, and slid her arm through Alessandro’s.

“I do hope you will escort me, Alessandro. I simply couldn’t bear to walk in on the arm of one of my brothers.”

That was a bit thick, I thought. Lysander was already steering Violante to the door, and Plum was busy trying to lever Aunt Dorcas out of her chair. But Alessandro was too well bred to point this out. He merely bowed and smiled graciously at her.

“It would be my honour, Lady Bettiscombe.”

I turned to Lucian Snow with a smile. “Certainly.”

I took his arm, and he favoured me with a smile in return, a charming, dimpled smile that doubtless made him a great pet of the ladies. His features were so regular, so beautifully proportioned, he might have been an artist’s model. One could easily fancy him posed in a suit of polished armour, light burnishing his golden hair, his spear poised over a rampant dragon. St. George, captured in oils at his moment of triumph.

“I must tell you, Lady Julia, I was not at all pleased at being invited here tonight,” he said as we passed through the great double doors. Those warm spaniel eyes were twinkling again.

“Oh? And why not? Are we as fearsome as all that?”

“Not at all. But his lordship has been gracious enough to invite me to dine at least once a fortnight since I came to Blessingstoke, and I have gained half a stone. Another few weeks and I shall not be able to fit through that door,” he said, his expression one of mock horror.

My gaze skimmed his athletic figure. “Mr. Snow, you are baiting me to admire your physique. It will not serve. I am an honest widow, and you, sir, I suspect are an outrageous flirt.”

He laughed and gave my arm a friendly squeeze. “I know it is entirely presumptuous of me, Lady Julia, but I think we are going to be very great friends.”

I raised a brow at him. Curates in country villages were not often befriended by the daughters of earls. But our village was a small one, and Father rarely stood on his dignity. He preferred the company of interesting people, and would happily speak with a footman over a bishop if the footman had better conversation. He must have made something of Snow for the curate to have been invited to dinner so often, and Snow seemed to be preening a bit under his favour.

The curate leaned closer, his expression mockingly serious. “I have offended you by my plain speaking. I am struck to the heart with contrition.” He rolled his eyes heavenward, and thumped his chest with a closed fist.

“Gracious, Mr. Snow, are you ever serious?”

He rolled his eyes down to look at me. “On a very few subjects, on a very few occasions. I shall leave it to you to find them out, my lady.”

He was an ass, but an amusing one. I primmed my mouth against the smile that twitched there.

“I shall look forward to the discovery,” I said solemnly. We exchanged a smile, and I thought then that this might very well be the most interesting house party that Bellmont Abbey had seen since Shakespeare had spent a fortnight here, confined to bed with a spring cold. Of course, I was entirely correct about that, but for reasons I could never have imagined.