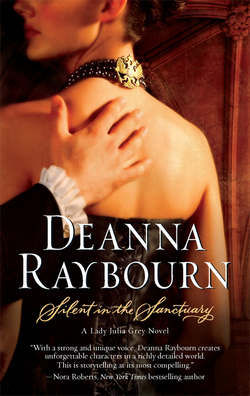

Читать книгу Silent in the Sanctuary - Deanna Raybourn, Deanna Raybourn - Страница 7

ОглавлениеTHE THIRD CHAPTER

How like a winter hath my absence been from thee. —SONNET 97

The journey to Blessingstoke was quickly accomplished. The tiny station was nearly deserted. As it was a Monday, and still nearly four weeks before Christmas, the village folk were about their business, although a peculiarly spicy smell hung in the air, the promise of holiday preparations already begun.

Father had sent a pair of carriages for our party, and a baggage wagon besides. There was a brief tussle over who should have custody of the hamper of food, but Portia prevailed, and I made certain to find a seat in her carriage. Somehow she managed to maneuver Alessandro into our small party, and Plum as well, leaving the newlyweds with the maids and the dogs. When Morag let her out of her basket, Florence perpetrated a small crime against Lysander’s shoe, and I made a mental note to ask Cook to find her a nice marrow bone when we arrived at the Abbey.

No sooner had we left the station than word spread we had arrived. It was possible to watch the news travel down the road, just ahead of the carriages, for as we bowled past, villagers emerged from their cottages to wave. The blacksmith raised a glowing red poker in greeting, and Uncle Fly—the vicar and a very great friend of Father’s—lifted his hat and bellowed his regards. There was a stranger with him, a handsome, well-groomed gentleman who eyed us with interest as we passed. He was soberly but beautifully dressed, and he swept off his hat, making us a pretty little courtesy. His eyes caught mine and I noticed a small smile, only slightly mocking, playing over his lips. His expression was merry, comfortably so, as if laughter was his habit.

“That is not a serious sort of person,” I observed as we rounded the bend in the road, leaving Uncle Fly and his jocular stranger.

Portia snorted. “That is Lucian Snow, Uncle Fly’s new curate. I made his acquaintance when Jane and I were down this summer.”

“Surely you jest. I would never have taken him for a churchman.”

“Father says Uncle Fly is having the devil’s own time with him. He is always haring off to one of the other villages to ‘minister to the flock’.”

“Oh, dear,” I murmured. “I do hope that is not the phrase he uses. How terribly earnest of him.”

“Indeed. I imagine Father will have him to dinner whilst we are in residence. He will certainly invite Uncle Fly, and he can hardly fail to include the curate. Plum, I know you are an atheist, dearest, but do mind your manners and try to be civil, won’t you?”

Plum, whose only interest in Italian churches had been the artworks they so often housed, gave a scornful look. “If Father is kind enough to supply me with game, it would be churlish of me not to join the hunt.”

“That is a terrible metaphor. Mark what I said and behave yourself. Oh, look there. I see the Gypsies are in residence, just in time for the holiday.”

Portia pointed to a cluster of brightly painted caravans in the distance. Tents had been pitched and cooking fires kindled, and at the edge of the encampment a bit of rope had been strung around to keep the horses penned. I imagined the men, sitting comfortably in their shirtsleeves in spite of the crisp air, mending harnesses or patching a bit of tin, while the women tended the children and the simmering pots. As a child I had joined them often, letting them plait flowers into my hair or read my fortune in the dregs of a teacup. But now the sight of the camp brought back other memories, bitter ones I wanted only to forget.

Deliberately, I turned from the window. “Alessandro, tell me how you like England thus far.”

The rest of the drive was spent pleasurably. We pointed out local landmarks to Alessandro, and he admired them enthusiastically. It is always pleasant to hear one’s home praised, but it is particularly gratifying from one whose own home is crowned with such delights as the Duomo, the Uffizi, and of course, David.

Our points of interest were somewhat more modest. We showed Alessandro the edge of the Downs, rolling away in the distance like a pillowy green coverlet coming gently to rest after being shaken by a giant’s hand. We guided his gaze to a bit of Roman road which he complimented effusively—a bit disingenuous on his part, considering that Florence was founded as a siege camp for Caesar’s army. We pointed out the woods—a royal hunting preserve for ten centuries—that stretched to the edge of the formal gardens of Bellmont Abbey.

Just past the gatehouse, the drive turned flat and smooth and I explained to Alessandro that this was where, as children, we had raced pony carts.

“All of you? The Lord March must have owned a herd of ponies for so many children,” he teased.

“No, my dear signore,” Portia corrected, “you misunderstand. We were hitched to the pony carts. Father thought it a very great joke when we were behaving like savages to harness us up and have us race one another down the drive. It worked beautifully, you know. We always slept like babies afterwards.”

Alessandro blinked at her. “I believe you are making a joke to me, Lady Bettiscombe.” He looked at me doubtfully. I shook my head.

“No, I’m afraid she isn’t. Father actually did that. Not all the time, you understand. Only when we were very, very naughty. Ah, here is the Rookery. This dear little house was originally built in the eighteenth century as an hermitage. Unfortunately, the sitting earl at the time quarrelled with his hermit, and the house was left empty for ages. Eventually, it was made into a sort of dower house.”

“It is where we keep the old and decrepit members of the family,” Portia put in helpfully. “We send them there and after a while they die.”

“Portia,” I said, giving her a warning look. Alessandro was beginning to look a bit hunted. She took my meaning at once and hastened to reassure him.

“Oh, it is a very peaceful place. I cannot think of any place I would rather die.” She smiled broadly, baring her pretty, white teeth, and Alessandro returned the smile, still looking a trifle hesitant.

“There,” I said, nodding to a bit of grey stone soaring above the trees. “There is Bellmont Abbey.”

The drive curved then and the trees parted to give a magnificent view of the old place. Seven hundred years earlier, Cistercians had built it as a monument to their order. Austere and simple, it was an elegant complex of buildings, exquisitely framed by the landscape and bordered by a wide moat, carp ponds, and verdant fields beyond. The monks and lay brothers had laboured there for four hundred years, communing with God in peace and tranquillity. Then Henry VIII had come, stomping across England like a petulant child.

“King Henry VIII acquired the Abbey during the Dissolution,” I told Alessandro. “He gave it to the seventh Earl March, who mercifully altered the structure very little. You’ll notice some very fine stained glass in the great tracery windows. The Cistercians had only plain glass, but the earl wanted something a bit grander. And he ordered some interior walls put up to create smaller apartments inside the sanctuary.”

Alessandro, a devout Catholic, looked pained. “The church itself, it was unconsecrated?”

“Well, naturally. It was a very great space, after all. The Chapel of the Nine Altars was made into a sort of great hall. You will see it later. That is where the family gathers with guests before dinner. Many of the other rooms were left untouched, but I’m afraid the transepts and the chapels were all converted for family use.”

Alessandro said nothing, but his expression was still aggrieved. I patted his hand. “There is still much to see of the original structure. The nave was kept as a sort of hall. It runs the length of the Abbey and many of the rooms open off of it. And the original Galilee Tower on the west side is still intact. There is even a guest room just above. Perhaps we can arrange to have you lodged there.”

Alessandro smiled thinly and looked back at the towering arches, pointing the way to heaven.

“How wonderful it looks,” I breathed.

“That it does,” Plum echoed. He looked rather moved to be home again, and I remembered then it had been nearly five years since he had seen the place.

“È una casa molto impressionante,” Alessandro murmured.

The great gate was open, beckoning us into the outer ward. A long boundary wall ran around the perimeter. Original to the Abbey, it was dotted with watchtowers, some crumbling to ruin. Just across the bridge and through the outer ward was the second gate, this one offering access to the inner ward and the Abbey proper. The horses clattered over the bridge, rocking the carriage from side to side. Overhead, emblazoned on the great stone lintel was a banner struck with the March family motto, Quod habeo habeo, held aloft by a pair of enormous chiselled rabbits.

“‘What I have, I hold’,” translated Alessandro. “What do they signify, the great rabbits?”

“Our family badge,” Plum informed him. “There is a saying in England, a very old one, ‘mad as a March hare’. Some folk say it is because rabbits are sprightly and full of whimsy in the spring. Others maintain the saying was born from some poor soul who spent too much time in the company of our family.”

I clucked my tongue at my brother. “Stop it, Plum. You will frighten Alessandro so he will not dare stay with us.”

Alessandro flashed me a brilliant smile. “I do not frighten so easily as that, dear lady.”

Portia coughed significantly, and I trod on her foot. We passed through the second gate then to find the inner ward ablaze with the reflected light of a hundred torchlit windows. “Ah, look! Aquinas is here.”

The carriage drew to a stop in the inner ward just as the great wooden doors swung back. Led by my butler, Aquinas, a pack of footmen and dogs swarmed out, all of them underfoot as we descended from the carriage. Aquinas had accompanied me to Italy but had returned to England as soon as he had delivered me safely into the care of my brothers. I had missed him sorely.

“My lady,” he said, bowing deeply. “Welcome home.”

“Thank you, Aquinas. How good it is to see you! But I am surprised. I thought Aunt Hermia wanted you to tend to the London house while they were in the country. I cannot imagine Hoots has been very welcoming.” The butler at Bellmont Abbey was a proprietary old soul. He knew every stick of furniture, every stone, every painting and tapestry, and cared for them all as if they were his children. He was jealous as a mistress of anyone’s interference in what he regarded as his domain.

“Hoots is incapacitated, my lady. The gout. His lordship has sent him to Cheltenham to take the waters.”

“Oh, well, very good. He wouldn’t be much use here, barking orders from his bed. I suppose you’ve everything well in hand?”

“Need your ladyship ask?” His tone was neutral, but I knew it for a reproach.

“I am sorry. Of course you do. Now tell us all where we are to be lodged. I am perished from thirst. A cup of tea and a hot bath would be just the thing.”

“Of course, my lady.”

The second carriage arrived then, followed hard by the baggage cart. There was a flurry of activity as I made the introductions. Plum and Lysander had met Aquinas in Rome, and Portia was a favourite of his of long-standing. But he seemed particularly pleased to meet his compatriots. He offered a gracious greeting to Alessandro and advised him that he had been assigned to the Maze Room, one of the best of the bachelor rooms.

“Oh,” I said, turning to Aquinas, pulling a face in disappointment. “I thought Count Fornacci might have the room in the Galilee Tower. Quite a treat for a guest, what with the bell just overhead.”

Alessandro shied and I gave him a soothing smile. “It never rings, I promise. It’s just an old relic from the days of the monks, and no one has bothered to take it down.”

Aquinas cut in smoothly. “I regret that one of his lordship’s guests is already in residence in the Tower Room, my lady. I believe Count Fornacci will be very comfortable in the Maze Room.”

I sighed. “Perhaps you are right. It’s warmer at least.”

Aquinas bowed to Alessandro. To Violante he was exquisitely courteous, and upon hearing his flawless Napolitana dialect, my sister-in-law embraced him, kissing him soundly on both cheeks.

“That will do, Violante,” Lysander said coldly. She ignored him, kissing Aquinas again and chattering with him in Italian. Aquinas replied, then bowed to her and addressed his remarks to Lysander.

“Mr. Lysander, I have put you and Mrs. Lysander in the Flanders Suite. I hope you will find everything to your satisfaction.”

Lysander gave him a sour look, collected his wife, and disappeared into the Abbey. Aquinas turned back to the assembled party. “Lady Bettiscombe, you are in the Rose Room, and Lady Julia is next door in the Red Room. Mr. Plum, you are in the Highland Room in the bachelors’ wing. Signore Fornacci, if you will follow me, I will make certain the Maze Room is in perfect readiness for guests.”

That was as close as Aquinas would ever come to admit to being unprepared. We had arrived with an unexpected guest, but Aquinas would forgo his own supper before he let it be known that all was not completely in order. We trooped into the hallway and Aquinas turned. “His lordship is in his study. He asked not to be disturbed and said he would see all of you at dinner. The dressing bell will sound in an hour and a half. I shall order tea and baths for your rooms. I hope that these arrangements are satisfactory.”

He bowed low and turned to unleash a torrent of orders upon the footmen. In a matter of minutes we were whisked upstairs, separated according to our gender and marital status. Portia and I were in the wing reserved for single ladies and widows. Formerly the monks’ dorter, it was now the great picture gallery, with our rooms opening off of it. Dozens of March ancestors gazed down at us from their gilded frames, punctuated by enormous, extravagant candelabra and a number of antiquities, some good, some of doubtful provenance. There were statues and urns, one or two amphorae, an appalling number of simpering nymphs, and even a harp of dubious origin. No weapons though. Those were reserved for the bachelors’ wing in the former lay brothers’ dormitory. Their paintings were all martial in subject, with the occasional seascape or Constable horse to provide a respite from the bloodshed. Between them hung arquebuses and crossbows, great swords and axes for cleaving, and in between perched suits of armour, some a bit rustier and more dented than others. I preferred the ladies’ wing, for all its silly nymphs.

Some time later, after I had enjoyed a hot bath and a pot of scalding sweet tea, I was sitting in front of a roaring fire, enjoying the solitude, too drowsy to rouse myself. Morag had gone to her room to whip the fur back onto my glove. I had bribed her with a plate of fruitcake to take Florence with her, and I was very near to dozing off when there was a scratch at the door. Portia entered, already dressed in a magnificent gown of heavy oyster satin trimmed in puffs of sable.

“Portia! You do look spectacular. You will put us all to shame as country mice. What is the occasion, pray tell?”

She flopped as far as her corset would permit into a velvet gilt armchair and pulled a face. “I am meant to be the hostess, remember? I have to look the part, and make certain I am the first one in the drawing room to welcome our guests.”

“Thank heaven for that. I thought I had dozed off and slept through the dressing bell.”

Portia waved a lazy hand. “You’ve ages yet. So, what do you think of our new sister-in-law? I think she is just what Lysander needed,” she said, a trifle smugly. Lysander had been rather brutal in his criticism of Portia’s marriage to Bettiscombe, a sweet hypochondriac nearly thirty years her senior. No doubt watching Lysander and Violante bicker from London down to Blessingstoke had been rather deliciously gratifying for Portia.

“Don’t be so cattiva,” I warned her. “We have all made mistakes.” We were silent a moment—both of us, I imagine, thinking of our marital woes.

“I am rather surprised Father wasn’t present to greet us,” I put in finally, breaking the somber mood that had befallen us.

Portia shrugged. “You heard Aquinas. He is doubtless up to some mischief. I had a guest list from him in my room, so at least I know the names. Aquinas, bless him, had already ordered the meal and prepared the seating arrangements, so there was nothing for me to do but approve them.”

“And with whom shall we be dining?” I asked, yawning broadly.

“Heavens, I do not know half of them. Uncle Fly, of course, and Snow, the curate. Oh, and Father has apparently decided to begin his Christmas charity early—Emma and Lucy Phipps are here.”

“You are in a foul mood, dearest. Perhaps you’d better have some whiskey before you go down.”

She tossed a cushion at me and I caught it neatly, tucking it behind my head. “Besides, I always liked Emma and Lucy. They were nice-enough girls.”

“But so desperately poor, Julia. Did it never trouble you, the way they would simply stare into our wardrobes and fondle our clothes? And Emma always read my books without asking leave. It was rude.”

“She is our cousin! And she was our guest, in case you have forgotten.”

Portia gave a little snort. “I was never permitted to. Every Easter for a fortnight. The dreadful orphans come to gape at the earl’s children like monkeys in the zoo.”

“You are a dreadful snob. Their lives were appalling. Can you imagine what it must have been like to live with those terrible old hags?”

She shivered, and we fell silent again. Emma and Lucy’s history was not a happy one. Father’s youngest aunt, Rosalind, had been a great beauty, the toast of Regency London, showered with a hundred proposals of marriage during her season. But she had scorned them all, eloping in the dead of night with a footman. Proud as a Roman empress, she took nothing from her family, and suffered as a result. They were desperately poor, and a series of miscarriages left Rosalind in poor health, her body ailing and her beauty wrecked on the shoals of her pride. At last she had a healthy child, but poor Rosalind did not live to see it draw breath. Her three sisters swooped in and took the infant from its father, or to be entirely accurate, bought the child, for ten pounds and a good horse. They called her Silvia and raised her in seclusion, as they believed befitted the issue of such a scandalous marriage, and it was no great surprise to anyone when Silvia went the way of her mother. She married a poor man without the blessing of her family, and lived to regret it. Silvia, too, bore half a dozen dead children, with only Emma to show for it. Ten years later, Lucy was born, and Silvia was buried by her aunts who clucked sorrowfully and gathered up the motherless girls and took them home. Their father vanished from the story, although Emma, an inveterate teller of tales, claimed he was a pirate prince, sailing the seas until he had amassed enough treasure to bring his daughters home. I never had the heart to scorn her for the lie. The aunts took the girls in their turn, sending them to the Abbey every Easter, for what they called “their respite”. I had had some idea that they had been educated for governessing or work as ladies’ companions. I had not seen either of them in years, and I was curious as to what had become of them.

“What have they been doing these last years? I have not had news of them.”

Portia shrugged. “Emma took a post some years ago as a governess. She has been with a family in Northumberland.”

“Good gracious,” I murmured. “One must pity her that.”

“Indeed. And Lucy has been in Norfolk, looking after Aunt Dorcas.”

I pulled a face. Aunt Dorcas was, in fact, Father’s aunt, which made her only slightly younger than God Himself. She was one of the trio of frightening old aunts Father called the Weird Sisters. These were the aunts that had had the raising of Emma and Lucy, and apparently Lucy had not yet managed to effect her escape.

“Poor child. Not much of a life for either of them, is it? Emma bossing other people’s children about, and Lucy tending to that horrid old woman. I can’t imagine which of them has the worst of it.”

Portia arched a brow at me. “There but for the grace of God, dearest.”

I nodded. “We are indeed the lucky ones. Now who else has been invited?” I asked Portia, stretching out my foot toward the fire.

“A pack of gentlemen I do not know, including Sir Cedric Eastley—I believe I have heard Father mention him, though I cannot recollect why—and a Viscount Wargrave, whoever he may be. Doubtless he will be a thousand years old and spend all of dinner leering down my décolletage. Then there is a fellow called Ludlow, and a Mrs. King, some relic of Aunt Hermia’s, I’m sure. And of course, Aunt Dorcas.”

I blinked at her. “You are joking. She must be nearly ninety.”

“Nearer eighty,” Portia corrected, “and with a host of indelicate habits, the likes of which I shall not alarm you with.” She paused and her expression turned thoughtful. “Hortense is here.”

“Is she? How lovely! She wrote the most delightful letters when I was abroad. I shall be exceedingly pleased to see her.”

Portia’s eyes narrowed. “You are a singular woman, Julia. I would have thought, given her notoriety, you might have found it a bit much that Father invited her.”

“It seems a curious sort of hypocrisy to object to Hortense on the grounds that she was once a courtesan. Aunt Hermia has been rescuing prostitutes for years and forcing them on us as maids. Consider Morag,” I reminded her. Morag had been one of Aunt Hermia’s most doubtful successes. She was skilled enough, but entirely incapable of keeping a position with anyone who expected a conventional maid.

“Yes, but Father. He seems quite smitten with her. What if he marries her?”

“Then I shall give them a nice present and ask if I may be a bridesmaid.”

“Ass. You are not taking this at all seriously.”

“Because it is ridiculous. Father is nearly seventy, Hortense will not see sixty again. And she is delightful besides. Who are we to thwart their happiness?”

Portia nodded slowly. “I suppose you are right. Still, I would have thought you would have minded about her. Because of Brisbane.”

She was watching me closely, and with some effort, I forced my voice to casualness. “The fact that she was Brisbane’s mistress twenty years ago is no concern of mine. Their liaison ended decades ago. Besides, his affairs are his own business. I told you that on the train.”

“I know what you said, Julia, but that is not necessarily what you believe. You are a faithful creature. I would be quite surprised if you were not still harbouring a tendresse for him.”

“I thought you were the one encouraging me to molest our young houseguest with unwelcome attentions.”

She snorted. “If you believe your attentions would be unwelcome, you are dafter than I thought. Do not think I failed to notice, dearest, you did not deny you still have feelings for Brisbane.”

“Then let me do so now. Nicholas Brisbane is a person I will always think of with affection, for more reasons than I can enumerate. But as for any sort of future with him—”

The dressing bell sounded before I could finish, for which I was rather grateful.

Morag appeared then, and Portia tarried a few moments longer, bullying Morag into piling my hair onto my head. I had cropped it some months before, but had let it grow during my travels, and with a bit of artful pinning it looked quite becoming. Portia left as Morag was buttoning me into a severe crimson satin gown. There was not a ruffle or furbelow to be found on it, not the merest scrap of lace or tiniest frill. The simplicity was startling. I powdered my nose lightly and daubed a bit of rouge onto my cheeks, touching my lips with a rosy salve I had purchased in Paris. Morag grumbled about whorishness—a bit of duplicity, I thought, given her own past—but I ignored her and motioned for her to fix my earrings to my lobes. They were delicate things of twisted wires set with tiny seed pearls and bits of garnet. They were not costly, but they were very pretty and whenever I moved my head they glittered in the candlelight. I rose and instructed Morag to keep the fire hot to make plenty of coals for the bedwarmers. She trudged out, grumbling again, and again I ignored her.

I started from the room, then as an afterthought, Portia’s words ringing in my ears, I hurried to my writing table instead. My morocco portfolio lay atop it, still clasped since I had last seen it in Italy. I snapped it open and scooped up the pendant Brisbane had given me. It took but a moment to secure it at the base of my throat. I paused to look at my reflection, surprised to see my colour was high. I must have over-rouged, I thought, wiping at my face with a handkerchief. I told myself I needed the pendant because the neckline of my gown was too revealing for a family dinner, but the truth was I had a dozen pendants more suitable, and scores of fichus and scarves that would have served just as well. If I had stopped to consider the matter, I might have realised I had put it on because now I was back in England what I longed for most was to see Brisbane again.

But I did not consider. I wore it as a curiosity instead, a piece of interest I might have bought in Italy. I could wear it among my family and no one save Portia would know it had been given to me by a man who had caused me more disappointment and more elation than any other I had ever known.

The dinner bell sounded as I left the room, and I hastened down the gallery. For all his eccentricities, Father disapproved of tardiness. I fairly flew down the staircase and along the corridor to the nave. From there it was some distance to the hall, but I could see the great wooden doors, fifteen feet high and propped open, light spilling over the great stones of the floor. Just outside the doors, in what had been one of the tiniest chapels, stood Maurice, the enormous stuffed bear one of our great-uncles had brought home as a trophy from a hunting expedition to Canada. He was a frightful old thing, with huge, sharp yellow teeth and claws that had terrified me as a child, and the bear bore him a striking resemblance. But now the bear was moth-eaten, and looked slightly embarrassed at the bald patches where we children had rubbed off his fur from too many games of sardines. I lurked behind him for a moment to catch my breath. The nave was deserted, the long shadows stretching empty up to the webbed hammerbeams of the ceiling. It appeared everyone else had already arrived. I took a slow, calming breath, then slipped through the doors.

As the Chapel of the Nine Altars, the hall had been built on mammoth proportions, and it had not been altered much over the years. A massive space, its walls were punctuated with nine curved bays that had once housed the altars of the most sacred place of the Abbey. The original stone had not been panelled, and the effect was impressively medieval. Tapestries warmed the stones instead—great, heavy things that told the story of a boar hunt in exquisite detail and rich colours that had grown gently muted over the centuries. Two of the bays had been converted to monolithic fireplaces, and in front of them wide Turkey carpets had been laid, although their silken pile did little to drive out the chill of the floors. Sofas and chairs were huddled near the hearths where fires blasted up the chimneys. In summer, lit with sunlight from the enormous tracery windows, the room was beautiful. On a cold winter’s night, it was just this side of miserable. The other guests had already assembled, gentlemen doubtless grateful for their elegant coats of superfine, while the ladies shivered with bare shoulders. They were gathered near the hearths like wintering animals, and I saw Alessandro in particular looking rather pinched about the face. I noticed that Aquinas was moving about, pouring hearty measures of whiskey to ward off the cold. Portia’s doing, no doubt.

She came toward me, her colour high and her eyes bright. “Dearest, where have you been? You’ve been an age. I was just about to go and look for you.”

“The bell just rang,” I began, but she was already towing me across the room to where Father stood in conversation with another gentleman whose back, in beautifully tailored black, was facing me.

“Julia!” my father boomed, in delight, I think. I kissed him, breathing him in as I did so. Father always smelled of books and sweet tobacco, a receipt for comfort.

“Good evening, Father. I was terribly slighted that you were not available to welcome me, you know,” I teased him, smoothing his wayward white hair. “I might think you had forgotten I am your favourite.” It was a joke of long-standing among us children to make him admit he loved one of us best. None of us had ever caught him out yet.

Father smiled, but I sensed somehow it was not at my little jest. There was something more there, some greater mischief, and I knew, even before the gentleman turned to face me, that I was the hare in the snare.

“Julia, my dear, I believe you already know Lord Wargrave.”

And there in front of me stood Nicholas Brisbane.