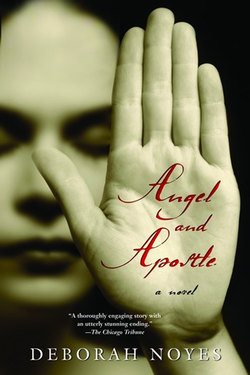

Читать книгу Angel and Apostle - Deborah Noyes - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ALL LIFE IS BARTER

ОглавлениеChance soon brought my mother and me to Simon’s father’s door. Or I should say Mistress Weary of this World brought us. As we walked along the forest path my restless gait more than once nearly knocked the basket from Mother’s arm. She moved as ever with a stiff grace, a certainty that had been my comfort over the years. I could always retreat into her colorless skirts or call her hand to my shock of hair when I needed such soothing, and I fought still and viciously to call that right my own.

The air was full of chatter. Cardinals sang, and pigeons thickened the trees. The dappled air rang with portent. I found an oriole’s feather on my walk and twirled it round and round my cheek, enjoying its silky scraping, then tucked it behind my ear. I hoped very much to have a glimpse of the dying woman, for Simon had assured me that a physician newly arrived from England, a Dr. Devlin—whom I had lately glimpsed from one hiding place or another on the Milton property, leaving with his physician’s bag, but whose name and aspect I had not hitherto encountered in my charitable travels with Mother—had already been and gone from her side with his herbs and potions. Now it was her loosening soul men would care for as best they could. Servants and neighbors, able volunteers like my mother, would tend the wasting frame and failed flesh.

Mother hesitated outside the door, intent as ever upon society and its hostilities, her milky hand raised to knock. She shooed me as always and bade me keep close to the house, but she didn’t close the door behind her; I saw not Simon or Liza or the father inside, but I heard a woman’s weak voice cry, “Enter,” and watched my mother, basket on arm, glide in like a gray mist and vanish.

Mother always left the door ajar, as if she might need its opening for a hasty retreat. The shadows called to me, and I found myself carried in past pegs with coats and cloaks hanging, on into the large hall, larger than our entire cottage, not lavish but unusual in that it was not entirely dedicated to implements of work and hard-won comforts. There was an explosion of color on the table, where a pristine rug with an exotic design had been draped, and a lovely carved desk on which rested a pewter tray with an inkwell and pounce pot and a hole full of quills. Above it hung a worn, ornate map penned with all manner of colored inks. I studied this at some length, noting serpents and other exotica in the far-flung seas.

There were many pewter plates, and there was more glassware than I had ever seen in one place. Even the light streaming through the leaden panes of the window casements held a silvery promise because there was more of it. The room where I lived with Mother was ever dark, even on the brightest spring day. Here was little dust to speak of, and no sooty film on everything. And on a shelf were books! Ten or twelve leathery volumes of different thicknesses, some with lettering of lovely engraved gold. One I knew, as the dame teacher used its dreary contents to help those of us who had outgrown the horn, but the others, like the great rug and the shimmer of glass and pewter, seemed to speak in a voice full of secrets.

I did not see his image until I had been staring a long while at the paintings on the wall at the back of the great hall. Even in the gloom I could make out the face closest to the hearth and appreciate its similarity to Simon’s angular mug (though I suspect it was, like the others, a sickly likeness). There was a drawn melancholy about this face, a darkness in the forthright stare that made it both fearful and fascinating to look at. The jaw was even harder than Simon’s, the nose sharper, and I wondered at this family’s greatness that its sons were objects of an artist’s brush. I couldn’t look away. Who had made this painting, and the others in the hall, and why waste them here on the dark rear wall?

Now and then I heard in the room beyond rustling or my mother’s soft voice, the voice reserved for the infirm.

Near the small feather bed in a corner where Simon must have slept so as not to disturb his mother in the room beyond, I found a flock of carved figures, crooked little beings from another world, neither animal nor human nor faery. I nearly made off with the smallest and finest—had it in my itching hand and would have slipped it into my stocking were I not afeared to find my fingers in the stocks. It seemed part dragonfly, part fox, and I wondered was the skewed shape of this and the other carvings because he couldn’t see his handiwork, or did his mind, like mine, leave this world when it could? I put the fox-fly back and touched gently every surface in his house. My two quick hands roved over the pottery and the trenchers he ate his meat and pudding from, the blankets that covered him at night, the hearth by which he warmed himself, even the pallet on which Liza surely slept. But I returned often to glimpse that fine visage on the far back wall of the hall. He had not Simon’s luminous, scarred beauty but the sun-browned strength and sternness of a man; he was older, perhaps sixteen, I guessed, to Simon’s twelve or thirteen years, and he was more sure, with eyes that beheld the world if not his place in it. I thought then that I would have liked to be the artist who painted him, who sat that long in righteous study.

My mother’s voice in the room beyond the stairwell washed over me, coaxing, gentle, punctuated by the occasional startling groan or angry but ineffectual outburst of Mistress Weary of this World. There was nothing like it—pain—to stoke a body’s rage. Some stayed pious and stern till the end, but most didn’t. Many an ill-mannered invalid lashed the well with ugly mutterings. It was a wonder women like my mother endured, but they did, washing and stretching the limbs that seized up in resignation, scraping furry tongues and peeling soiled linen from beneath bodies limp or spotted with sores. As I stood that afternoon, furtively measuring the shape and state of my new friend’s home life—and the face on the wall that would haunt my future as surely as the letter “A” had my past—I felt curiously calm. I hovered at the corner desk, pulling the wooden chair out as quietly as possible to sit like a lady intent on addressing a letter to her beloved lord, and though I dared not search out and soil a sheet of paper, I schemed to leave behind some trace.

Instead of writing, which I did poorly, I skulked round the room and, having little else, laid the prized oriole feather from behind my ear on Simon’s canvas mattress. The little carved sentinels seemed to watch me stooping there.

It was then the door slammed with a great flourish, and I flinched.

“And what hath the cat dragged in?”

Before I could retreat, I found Liza’s hot breath on me and was made to witness the black of her back teeth when she spoke. “I know you. I know all about you. What right have you here?”

I gestured weakly toward the rooms beyond. “My mother is there, ministering to the sick.”

“Your mother might have left her woe at the threshold.”

I felt defiance build in me like March wind, though I tried as best I could to contain it for Mother’s sake. “I’ll go, then.”

“You right will go, child. And don’t let me see you sniffing round Master Simon’s feet anymore. You think yourself a stealthy little mongrel?”

“No.”

“He is a good boy,” she said, her voice falling flat. “Let us keep it that way.” She looked as weary as her whining mistress in the room beyond sounded. But there was a growing delirium in the other woman’s voice that tugged like a cord at Liza’s attention. She shooed me and strode down the narrow hallway holding her skirts, past the stern young eyes of the painting, and her leather soles slapped on the wood. By the time I fled into the light, the lady of the house was shrieking to high Heaven, as if her very soul had been offended. Only my mother could rouse such passions in a body.

• • •

It was a relief to flee into streaky sunlight, but I was restless there and longed to hear the mistress’s voice. Faint though her presence now was, she had borne Simon, and I was grateful to her. But with gratitude forming a sick knot in my stomach, I wished her dead and gone too. I crept along to the rear of the house, crunching old snow. The lady’s own window was sealed fast and draped inside with cloth, but faraway voices came floating through the casements of the window facing out from the adjoining room. Perhaps there was an inner door open between them, for with little effort of concentration I heard Liza’s hoarse instructions, low and impatient. My mother’s voice was strained and haughty. The invalid spoke not at all. Perhaps she had drifted off to sleep. Liza grunted as if under a weight, and I understood that she was struggling to draw the bed linens out from under the sick woman. “You might make yourself useful. I’ve changed that basin already.”

Mother said, “Command me, then. I’ve not come to be idle.”

“No, misspence of time is not your crime, I’m told.”

There was no reply, but more heaving and grunting. I felt provoked on Mother’s behalf. It was usual for perfect strangers to take a knowing, nasal tone in our presence, to own us with their verdicts.

“I see you’ve made yourself at home among our local gossips. And your hands are ever clean?” Mother challenged. Though I could scarce hear her low voice, its familiar edge—normally reserved for me alone—unnerved me. “I’ve not met a servant with clean hands yet.”

“You could eat off my hands,” said Liza. “What part of you hasn’t the devil had his touch to?”

“That may be,” Mother said in a monotonous tone of affliction, and then, hotly, “But I’ve not come here to suffer your abuse. I neither seek nor offer apology. They’ve had their due. I’ve paid my debt with years.”

Liza, like a horse, blew a great blast of air through her nose. “Your debt. In England—here too, for that matter—they might hang you for like offense.”

“They might do me a service.”

“Mind that tongue.” Liza’s lilting voice had snagged on disbelief and something else, pity perhaps; whether it was for Mother or the sick mistress she manhandled I know not. She huffed and murmured, “And you still a young woman. I hope the child won’t take your view. Damp this cloth,” she said. “What sinner won’t thank God for the life she’s given? Wring it, please. We want to cool her, not drown her.”

I waited for Liza to speak again but heard instead the drops of water in the basin as Mother squeezed the rag. I heard the buzzing of a fat bumblebee by my thumb and watched my breath come in foggy blasts against the boards. My cold hands were flat against them now, and my neck was cramped. After a grudging pause, during which Liza no doubt roughly shifted Mistress Weary’s ruined body on the mattress, her muffled voice told me that she and my mother had exchanged something in their silence—a look, an understanding. “Rest easy, miss. My hands are not so clean,” she said, “as to wave back mercy.”

“I know not,” Mother said as I begged to be told what had made the lady shout. “Death throes. She is far gone.”

“Did you kiss her hand? Did you damp her brow?”

“Yes, yes. I always do.”

“Did the house servant come screeching?”

“Yes,” Mother sighed, “like a harpy. But she helped me ease the good woman to her afternoon’s rest.”

“But why—”

“I know not, Pearl. Now go.” She rubbed her temples and slipped into our cottage. “Let me rest.” Mother closed the door lightly. I kicked it.

I kicked the door again and again, feeling wrath shoot through me. When she did not reopen the door, I pitched sticks and broken shells from the garden rim at the walls. Still she did not return to me. She wouldn’t, I knew. She would only when others were about and to placate me was to protect us both. Otherwise she let me rail. Often she threatened after these episodes to place me in service with a stern and godly family—the custom for older girls—but I think she knew not whom to ask. Though she and her infamous “A” were no longer so reviled, she would sooner do a favor than ask one.

I felt foolish in my violence and huffed and stomped down to the water beyond our cottage. I knelt on the ground and scowled at the rushes and clumps of scrubby trees that did little to conceal our humble cottage—though we were far enough from the nearest homestead not to want concealing—and rubbed cool sand on the tender flesh above my wrist until a red slash appeared. Then I fell into a heap on the little beach, curled like a restless infant to watch a distant sloop chase the sliver of pale moon. The sun was low behind the forest-covered hills of the mainland across the basin. The water shimmered. I shivered and sucked my sandy middle and forefingers and watched that boat, as if it carried my life and might soon crash against the rocks. Then I turned away from the tedious sea and surveyed the clearing beyond.

I may have sensed him before I saw him, but my eye soon fixed on a man stooped in a meadow west of our inlet. He had been collecting new herbs and now brought himself tall, regarding me. The basket swung at his elbow as he strode near with alarming purpose. The wind-blown grass made his lower half appear fogged, as if he did not walk so much as float forward.

As one forced by standing to loathe most everyone I knew, I was more than usually enamored of strangers, not cowed as one my age and size ought to have been. In fact, the striding figure was none other than Dr. Devlin.

The learned physician had come too late to ease Mistress Weary’s struggle, but Simon often parroted his older brother’s sentiment that Devlin was a thoroughly modern man of science. The community would do well to value him above the barber-surgeons, as he might effect a cure with his store of herbs and the treatments stored in the pages in his mind . . . before he bled you silly. Just now he looked quite mad, and the closer he came lurching, the madder he looked. His skin was sun-brown against the blackest hair I’d ever seen, blacker even than Simon’s, but just as unkempt and far too long for Puritan Boston. Surely some worthy would hunt him down with scissor and razor. The doctor had deep squint lines around the eyes that would have given him a perpetually merry look had the eyes themselves—strange hazel flecked with gold—not been so violently sad. These mournful eyes were older than he by far and seemed, at close range, awed at the mere sight of me. I frowned and pushed blown hair behind my ears. Like a bear lumbering stay back don’t step more or I’ll scream murder.

His pace did not change, though I brushed the sand from my skirts and rose, haughty before the ocean. The water now seemed distant and drowsy in the late light, calmly sparkling, but it was the one calm thing in this windy world, and I was poised and ready don’t come closer.

“There,” he barked cheerfully. “That will be our line.” He pointed with his staff to a half-visible nest in the tangle of last year’s shore grasses. “I won’t cross it if you in turn won’t scamper off like a rabbit.”

“Well, sir,” I braved with raised brow, “rabbits do not scamper. I believe they bound or spring.”

He sucked in gaunt cheeks, set down basket and staff, and settled hands behind his back. I trusted this humble posture not at all. “I see words matter to you, Pearl. I confess this pleases me.”

I did not ask why it should. Grown people were forever saying such things, and were like to mean almost nothing they said. “Goodman Baker would not wish to see you collecting his weeds,” I scolded. There were few on this earth I had license to scold, few who would not peer down at me with a rage of flared nostrils or produce a hazel switch, and I expect I recognized and loved those few instantly. “He does not like me on his beach or in his meadows. He spits his juice on my Sabbath shoes and calls me idle. He does not like even old Belle, the Prices’ mule, to tread over his lines—”

“Nor the birds to sing, I wager. But you are a famously idle girl, aren’t you, Pearl.” It wasn’t a question. It was his second challenge. He wanted a question from me, and I would not grant it how do you know my name how do you know me pearl pearl it is my name. Elders often knew things, took things I had not offered. His familiarity was of no concern to me. His uncanny stare and restless gait, though, were. He did not cross the bird’s-nest marker but seemed to hover at its border as a horse will before moving water. “Do you wonder what I want, Pearl?”

“Do you wish me to?”

He laughed through his nose. “You’re a clever child, but do you know that many fine feelings will desert you if you’re ruled by cleverness?” He took one step, not over but onto the line, where the nest should be. I backed away, imagining the eggs smashed and working up a fury for it when he squinted through the fingers of one hand raised against the glare. The lines radiating from his eyes bunched together and darkened like storm clouds, and his formerly playful voice now better matched the expression in those eyes—high-sorrowful and cloying. I can’t say the change suited me.

“Is that your mother’s cottage there, round the bay? Why does she live no more in her father’s big house in town, Spring Street I think it was? I’ve been gone some years, Pearl. I’ve only lately returned to these lands.”

“Spring Street?” The words were bland in my mouth. “No, she doesn’t live here or there. I have no mother.”

He smiled and looked bemused. “You must have a father, then?”

“Not in this world.”

What a hearty laugh, his. I did covet that laugh—the eyes were truly merry then—and it made me forgive him the despair that had come straying, stamping over our discourse as his heel had doubtless trodden the bird’s nest.

“Can you keep a secret, Pearl?”

“Not very well,” I said, “but I’ll rally for love of one.”

He dropped to one knee near his edge of our invisible line. “I know him—your father.”

My narrowed eyes cupped the sun and watered. I did not, would not, gnaw on my lower lip as blind Simon claimed of late to know I was doing whenever Liza happened near and frayed my nerves. How he knew, I can’t say.

“He sent me to you,” the doctor persisted.

Don’t invoke him. “You crushed them,” I cried, and my hand, eager for diversion, shot out toward the nest hidden in the grass.

He stood and plucked something from behind his ear, where nothing had been before. It was a single splendid oriole’s feather. He held it aloft on his palm.

“Are you a sorcerer?” I demanded, thrilled to my core, for it looked to be the very feather I had left behind for Simon.

“Take it.”

I did, nodding with slow delight and not a little irritation that Simon was now deprived of my offering.

“And come again at this time tomorrow with one morsel of life as it has been with you,” he paused, bringing a finger to whispering lips, “and your mother. Come here to our line, and we shall barter. But do not bring me untruths. In time you’ll have more than you can measure, a new bauble each day if you like—”

I did not ask what manner of morsel he meant but only skipped away, happily bewildered, and slipped the feather up my sleeve.

Inside I found Mother refreshed. I don’t know why I held my tongue about the doctor, but I did. It seemed no more proper or necessary that I sacrifice him to public scrutiny than if I’d glimpsed a doe in the wood with her fawn, or a nymph from my fancies stepping back through the bark of an oak (after which I would press my ear to its trunk to hear her heartbeat). These fleeting favors I would not share, even with Mother; they were mine, and too precious to part with, and now again some gracious instinct commanded me; I felt a proud discretion.

My parent—not the only one, it would seem, if the doctor were to be believed—had lit the reed lamp and was chopping turnips for stew. I put my head on my arms on the table to watch the blur of her knife. Her hands were able, like Simon’s, like my own, yet I never shed tears at my work.

“What hurts?” I asked, and she smiled dimly and shook her head.

“I shall kiss it,” I announced. She stopped her chopping and held out her knuckles. I traced them, the peaks and valleys, with my little finger and settled on one. “This one?”

Mother nodded, and I stooped with great ceremony to kiss the imaginary wound.

“Thank you, Pearl.” She was a clever player, for my sake. She smiled as if by all rights she was happy, and I took up another knife and quartered the onion. When my eyes teared, I made a great show of it, and even ceased chopping to give Mother time to repay a sweetness. But she did not. Instead she brushed the turnip chunks onto a trencher and carried them over to the kettle. She knelt by the fire. I fingered the feather in my sleeve, and my play pain burned on like a lonely candle.

That night and all the next day it rained and rained, and the ocean roared. Mother made me stay indoors and spin, but by supper I was half mad with captivity. When she nodded off over her embroidery by the fire I escaped west toward the woods and there reveled in the violence, the water streaming into every rivulet, branches bending under the weight, spring rain sliding from bowed and swaying leaves. My dress was wet through before I noticed, my cloak like a heavy shroud, but I kept going until I reached the now familiar fence. I stood behind the great beech and studied the rear of Simon’s house. I wasn’t there long, shivering and feeling every bit the fool I was, when a muddy carriage drew up out front. I didn’t see who got out, as the house blocked my view, and in minutes the transport drew away again, the horses sputtering and shaking their manes in complaint.

I crept forward, holding my hood closed. It was hard to hear a thing, even with my desperate ear pressed close to the house. The window was shut tight and the rain pounded out its rhythm, but I knew the weather had changed inside the house. The muffled voices were not merry exactly, but there was something new in the current of them.

I pleaded in my mind for Simon to come out to the privy, but instead, after a time, Liza came and caught me by surprise, hissing and shooing at me with a stick, calling me a wretched little dog. She shook her head in utter disdain at the sight of me—dripping, my hood plastered against my cheeks. “You must be quite mad, child! Look at you, drowned!”

My voice died in my throat. I stuttered something incomprehensible and heard a man shout through the rain behind us, “Who’s there?”

“It’s that little dog I spoke of come sniffing again about my master’s door. I do think she’s smitten with your brother, sir.” She let go an undignified snort.

“Liza, your comportment lacks charity.”

In nary an instant his hair had been pasted to his angular face by the rain, his damp shirt molded to his chest. Oh, but he was beautiful, even wet; like a prince. My every limb felt locked. I wouldn’t have known how to differ when Liza chimed, “Be it so, young master, but this one has no business among christened infants. Her own mum bears the mark of the fiend at her breast.”

“The Good Father would not wish to hear you speak so, and pray you remember, Liza, your eyes are not His own. We are all born to sin.”

The servant blinked at his pious words and fixed her misty gaze on me. She bowed with mock gravity, a fuzz of gray hair dangling from her drenched cap. “Christ’s sake, there’s dye running in my eyes. Good sir and lady, I take my leave.”

Astonished—whether by the whole muddle, or her blasphemy, or the young man’s indifference to it, I know not—I found I was sucking on my fingers as I had as a babe and sometimes did still. I willed my rigid knees to unlock, but because of my twisted stance it was to the forest I curtsied, his presence a weight at my back. I fled to the safety of the trees, snagging my soaking cloak on the fence as I squirmed through. He called after me, and I looked back. Holding a hand above his eyes to shield them from the torrent, he urged me to come inside and get dry, but I kept running.

Raw to the bone, I tripped and splashed and stumbled all the way home, where Mother undressed me by the fire and rubbed me dry and wrung out my clothes and hung them. She begged me to be civil just once and let her soothe me, but instead I raged. I’d flourished on a diet of scorn all my young life, but this, a stranger’s sympathy, had caught like a bone in my unworthy throat. “Will they come and take me away and lock me in the prison for spying?” I sobbed, repelling her caresses. “Will they put me on the scaffold alone?”

But Mother, who had seen storms worse than this one, shook her head. She caught me close and sang into my hair, and we rocked by the fire. She blamed herself for my ways but without conviction, and I knew on that rainy night that my life was my own. It was the second priceless gift she gave me.