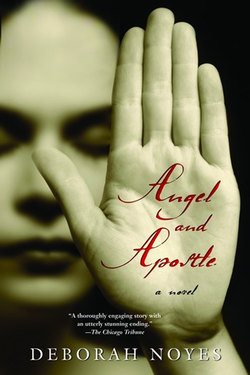

Читать книгу Angel and Apostle - Deborah Noyes - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

SIMON

ОглавлениеWhen I tell you that I honor my father, you will think me false. “The lies of an infant witch—” Simon once teased, “none but the prince of Hell has time for.”

Believe what I say, I shouted in jest, seething with disappointment. Whatever I say, or see me curdle your butter. It’s all sport to me.

Simon only laughed, as well he might. If it were true that I knew dark arts, I would have saved him while I could. I would have restored his sight and turned time back at the cellar door. Instead, at the inquest, I became invisible. When Nehemiah’s eyes looked for me there on the public floor, they found only my grief, puddled like his brother’s blood—a deeper color than ever Mother wore embroidered at her breast.

But before death there was a garden. There were children taunting, for I served as well as any Quaker the amusement of Boston’s godly youth.

It was the Lord’s Day, and we were idle—I with the sting of stones at my back, they shrieking like brats possessed. Because I knew that no pack of holy pygmies would brave the wood without master or mother, I ran and ran, willing myself be an otter and the shade be water. How cool it was and dark, my wilderness. How sweetly it repelled them. With their brat-threats dying in my ears I crashed through a thicket and found in a clearing, as stark as any miracle, a gabled house with a skinny lad in its kitchen plot.

How do I fashion him in your thoughts?

Let us say this boy was still, as still as marble, and riveting for it. What’s more, he was as stately in his solitude as the townsfolk I daily spied on (blasphemers and nose-pickers all) were shrunken in theirs. I would come again and find him on a little three-legged stool, milking his cow with deft hands, and again, when he would be whittling by the wall in the sun. But on this day he was sitting, just sitting on a house chair in the green-specked mud of the garden, with his strange, pale eyes shifting in their sockets. His hands were beautiful birds chained to his lap.

He must have heard me, but I stood and caught my breath, watching him. When it came my voice was still ragged from the chase. “Why have they planted you there in the shade like a mushroom?”

He looked not before him but straight up, as if my words came from beyond.

“Here,” I called. “Past the fence. By the beech tree.”

“I won’t find you there.”

“Why not?”

The boy I would come to know as Simon turned to my voice that Sabbath day, and I considered how much deeper his was than I might have imagined, a man’s voice, though he looked to be no more than a scrawny boy. Were I old enough to know better, I would have blushed. Instead I crept closer and scooped a handful of dry leaves from the ground. Leaning over the fence, I showered his boots with them. He did not look down.

“Have you no sight?”

“Who is it wants to know?” he demanded. “A girl pursued hither like a sow?”

“I do.” I caught my breath again. “Pearl.”

“And who is your father?”

“I have a mother.” I murmured her name, courting the barely perceptible nod, the gossip’s grin. It didn’t come. Then he was deaf, I mused, as well as dark. “And you,” I pronounced, arms crossed, “are a stranger here.”

“I’m new to this plot but not these shores. We come south from Cape Ann. My father’s at sea. My brother will be here yet.”

“And your mother?”

He tilted his head. The palms of his hands kneaded his knees. His every movement was slow and measured, nimble as a fox crossing a streambed. “Your voice travels,” he said. “First here.” One hand made a sweeping arc. “Now over there. Are you moving?”

“I am not.”

“Are you a pixie?”

I draped my arms over the fence rail, eyes narrow as a cat’s. “I am too old for games.”

“Are you a pity?”

“Indeed.”

He sniffed the air. “Come here, then. Let me smell you.”

I snorted, but this was grievously immodest, so I clapped a hand over my mouth. His answering smile was a miracle, and I giggled to hold it fast, though the giggling smacked of greed. Why he didn’t make haste to dismiss me then (we’re some of us overwilling and run our best chance ragged, trample it underfoot), I’ll never know.

He said: “A pretty pity too, I wager. With a pretty laugh.”

The hand at my mouth was raw with cold and streaked with blood from my stumbling flight through the woods. I licked a knuckle clean and pulled my cloak tight, backing away from the fence. Moving a few steps through crackling twigs (how thunderous the world became, listening with Simon), I hugged the smooth beech for balance and peered at him from behind it. The moment seemed suspended, and when his empty gaze did not release me I gave what payment I could: “You wondered how I smell?”

Well, then, mused the upraised chin. Tell.

“Mother says like rain.”

Still on his chair, the blind boy with the man’s voice nodded gravely, sweetly, and my legs felt free again.

My earliest memory is of Mother’s strong hands holding me under water. It’s no proper memory, I know, but my young life’s unrest contained, at last, by her confession.

Embattled, my mother came like a sleepwalker (she revealed on a night when I was bedeviled by dreams—a night years after the fact and one year or so before this story begins) to the water’s edge with the same infinite pragmatism that once prompted her mother’s kitchen servant to drown kittens or wring the necks of hens. Killing her bastard would mean sure and swift punishment. A noose round the neck, God willing.

“Didn’t you love me even a little?” I asked, shocked but not shocked enough, apparently, to leave it be though I was in my seventh or eighth year at the time (I don’t know my count exactly) and content, as children are, with the here and now. Mother nestled closer under the bedcovers. She stroked my sweaty hair, kissed my brow, and wished all watery nightmares gone. What she did not do was answer my question.

In the coming days her silence lingered, and my dread grew. Did not every mother love her babe? Though my own failed to reply, she filled my hands and hours with dainty shells, with stones made smooth by the sea, with salty crab claws and the strange, spiny remains of fish. She held my fingers as the waves sighed their ceaseless sigh at our feet, beckoning, and in time as we gazed forth together without fear into the emptiness, I felt safe again.

This earliest of memories, then, is a figment. But in this memory (let us call it that) my mother’s hands, like her face with its startled look, are prison-bleached and jaundiced. She cannot hold them steady. Kneeling, she lays the infant me on wet sand, her body quaking uncontrollably with the urgings of the waves and the vast glare of life outside prison walls. She believes (Heaven and Hell were snuffed like candles in that dank jail) that peace will come with a shroud.

Froth tickles, folds soaking over me, and though the cold shock of the surf little resembles the womb, its mild rocking does. So my infant brain has scant cause for alarm until I feel the crush of her cheek against my chest. Rigid with despair, Mother is counting my heartbeats, one two three four five six . . . and then she is a fog moving away with hopes the tide will have me. When the tide won’t or won’t hurry, she reaches out, and in her thoughts, her mother’s onetime kitchen maid is singing.

It is only when I cease to hear my mother’s mad humming, when my ears and lungs fill with airless, fractured light, that I make out another voice. This voice is muffled and aggrieved, reproachful but tender (as Mother’s shaking-strong hands had been, holding me under). And I am plucked like a coin from beneath the tongue of the sea.

It was days before Mother finally answered my question: “Did I love you then? I loved no one, Pearl. No soul on earth.” Though she said no more, her dark eyes spoke for her. Had she courage, I understood, she would have walked into the water with me that day—long before our Puritan minister wandered into that remote bay from some faery realm, striding to my rescue and into his life’s mission to right the wrong of my existence.

My father (though I knew him not then) has in his notebooks over the years made fanciful much of Mother’s courage, though he never named her in those pages as he did me. Had she the courage he claims for her, both Mother and I would have perished in the surf. Instead we retreated to our little cottage by the bay near Boston, there to endure a thousand petty persecutions, outlast our wary love, and bide our time until he could return to claim what was and wasn’t his. Even now, as a woman grown and with the mystery of my father solved, I cannot unpuzzle my mother. But in those days it was my heart and history that consumed me.

“What was it like up there?” I would demand, brushing Mother’s dark hair, which with its wave and furtive gloss seemed to me a living thing. “On the scaffold?”

If she considered her answer, her face concealed it. “I felt as a friend to the breeze.”

Even I, at best indifferent to society’s rules, being fatherless and scorned by all but her, could not forgive this woman—who wore by law the letter “A” on her dresses for my sake, she was not above reminding me—her upright carriage, her terrible calm. It was an affront. “This fine noon,” I countered, letting my voice grow mighty like the minister’s, “I was nearly stoned to death by cretins.” Words hot and relentless as the noon sun must have been that June day years before, scorching her prison-pale cheeks. I thrilled always (and this shamed as punishment never could) to imagine it: Mother exposed on the weathered platform of the pillory while the governor in finery, flanked by sergeants and ministers, scolded from the meeting-house gallery. Was it weeks or months afterward that she thrust me on the sea? Days?

I’d attended my share of public stripings and shamings—idle bond servants, Antinomians, vagrant Indians turned lewd by the white man’s spirits—and could well picture the greedy masses milling at her feet, snickering over apples and gnawed cheese rinds. What I couldn’t see was my own small self wailing in her arms with no history, no memory. Her shoulders had cried out from holding me that long three hours, she had confessed once in a rare show of self-pity. “My arms quaked like rushes in the breeze.”

This night she waited till I’d had my fill of brushing and then stood, shaking her mane and padding barefoot in her nightdress to her stool at the spinning wheel. The heavy thump and whir began, a savage rhythm I despised. Mother’s hands were never at home at the wheel as they were with needle and silk threads. In the light of the fire she looked at peace, but what mother would see her child stoned? The world would have me sewn up in my burial cloth, Mother oft accused, before I learned to master my tongue.

An owl called from the meadow west of our cottage, and I felt my blood tug toward the flames. I went and sat at her feet by the hearth, contrite, and rested my cheek against the warmth of her leg. I thought of tiny mice scattering for their nests as white wings beat the grass to a froth. And then my mind fixed on the boy Simon, imagining him at his table in useless candlelight or, like me, propped beside the popping flames, content to stare at nothing.

I roamed west to spy on my quarry the very next day, and the next, and another. On the third day, the house servant—a red-faced woman Simon called Liza—was balanced high on the roof cleaning the chimney. Her stout frame struggled with a rope that held fast what sounded to be a goose. As she lowered the great bird, she called out to Simon on his chair in the yard to aid her. He didn’t mind her overmuch as a rule, I soon noticed, though there was nothing imperious in his bearing until she started to scold. Now, as before, he kept his hands imprisoned on his lap, as if they might fly away. Once he even sat on them, but he seemed to know it was no proper posture and set the hands free in his lap again.

The March day was grayer than those previous, and more raw. Liza struggled, and the goose echoed in the chimney, honking and flapping inside the brick well. Liza both cooed to it and cursed it (though once I saw her look up and round with stealthy eye). Enjoying the sun on his face, Simon seemed not to know he was being watched.

Liza let go the dancing rope, and as she wiped her hands on her apron, there was a muffled thud and a great squawking from inside. “There, old girl, keep your head about you. Simon, run, open the door and let this infernal mother loose—”

Simon stood and walked with a hand brushing the wood and casements at the rear of the house. He was bony but sure, and I knew he would run and leap in the meadows if only his eyes would let him. I wished he might be my companion. I wished for him.

“Simon! I hear the just arse in there flapping soot all over!”

An instant later, he pulled open the door and out waddled the disoriented animal, black and indignant, trailing a soiled rope from its ankle. I could see the bird had once been white. Up on the roof, Liza clucked and brushed her hands together. She looked as if she might leap in one stout, easy motion through the air, but instead she disappeared from my sight huffing and sweating to where a ladder must have been propped on the other side of the house.

I’d had little sign of the man of the house, nor anyone but Liza pegging her old gray shift to the line or stooped over a kettle in the backyard brewing soap and Simon whistling among the hens, whittling (how I feared for him, but his hands knew the knife, it seemed, as they knew the worn knees of his breeches or the downy stubble on his chin) and trying, when his hands were empty, to tame them. Often he cocked his head to the side, as if listening to music only he could hear. I well understood this posture, this stillness. There was endless conversation in the spring air, but for Simon, I realized, sound must by all rights be like streaks of paint on his world’s canvas. Where was his mother? Where was the brother he had spoken of? He seemed so alone, yet content to be.

I couldn’t resist. I took an acorn husk and flung it. It landed at Simon’s feet and he started. With my hiss, a vague smile spread across his face. “It’s you,” he said.

“That was a goodly dance you did with that goose, Master Simon.”

“Now you have my given name. What’s yours, pixie? I won’t give you the advantage.”

“I told you, I’m Pearl.”

“I shan’t forget again.”

“You best not do.”

“And how long have you been hidden, Mistress Pearl?”

“I’ve been here three days or so. How long have you been without sight?”

“I’ve lost count—seven or eight year, I guess.” He toyed with a weed he’d plucked by his chair. “I still see shadows. Sometimes. Come, stand closer. Clear the fence.”

“No, I won’t. Your mother’s servant will skin me.”

“She’s harmless enough. Unless you’re a goose.”

We both laughed, and I moved out from behind the beech tree to the edge of the fence. I hung on it and studied him. “Why did a shadow pass your face just now when I spoke your mother’s name?”

“You didn’t speak it.” He was silent a moment before revealing, with weary candor, “She is Mistress Weary of this World.”

I said no more but tugged at the brush by the fence, weaving leaves into a length of vine I’d pried from the bramble. I fit them into a crown, my fingers moving fast, knowing the work well. But I felt Simon’s empty gaze and the shadow of the house like a specter in the corner of my eye.

“I’m weaving you a crown. Your dwelling is very fine. Is your father a great man?”

He considered a moment. “Maybe,” he said at length in a level, nearly cheerful voice. “He’s of the middling sort, a merchant. But his travels serve him well. And where is your father?”

Had he seen me, Simon would have kept mum, but he couldn’t know. He couldn’t see. “Mother says I have only a heavenly father,” I relented in a voice neither kind nor cheerful.

“My mistress will be gone before the Indian corn is ripe.” Simon settled back on his chair and cleared his throat like one ending a grim sermon.

“Well, then,” I rallied. “Now that’s done, I’ll tell you my story.”

“What story is that?”

“Of the sinner’s brand at Mother’s breast. She wears a red letter on her dress.” I lowered my voice for effect. “I would tell of her walk through the prison gates with a babe in arms.”

“What is all that to me?” he asked, but I could see that I had grown in stature in his estimation.

“Don’t you know they call me the devil’s spawn?”

He grimaced and leaned forward, speaking very low. “Then is my mortal soul in danger?”

“Oh, yes.”

“I don’t believe you.” Simon tilted his head to one side as if to listen for a change in me.

I looked left, right, and then climbed deftly between the shorn logs of the fence, my heavy dress trailing behind like the great tail of the peacock from the horn alphabet. I crept toward him and felt the drama of play fill my lungs. I had less play even than other Puritan brats in my early life and craved it exceedingly, even in that late hour of childhood. I wanted to fling my arms full round his thin neck and bury my face there. His icy eyes stared past me, his head still tilted like a fishing crane’s.

“Believe it,” I whispered and with great clumsy ceremony settled the crown on his tousled head. His nose twitched like a rabbit’s and his face looked pained, but I was off at a trot before he could speak. Every grateful part of me, every nervous inch of skin and blood-beat of my small heart, knew this strange boy for a promise. Life, at last, had made me a promise—how to account for it!—and I could not bask in him more that day for fear of being scorched by my own bliss.

As I whirled under the blurred canopy, I saw Master Simon in my mind’s eye. He would remove the crown cautiously, having never seen one. But he was not half afraid of me, like the others, and he would know this talisman of mine. He would touch every part of it, leaf and bark. He would hold it to his freckled nose, perhaps his tongue, as I would see him do with many objects in days to come. He would know every edge that my hands, or Other hands, had made.