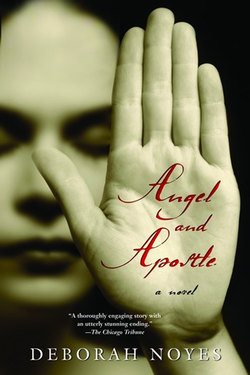

Читать книгу Angel and Apostle - Deborah Noyes - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ONE SOUL THAT KNOWS YOU

ОглавлениеI felt a hand on my shoulder and rolled awake in a blur of midnight black. Mother whispered, “Come, now. The governor is dying.”

I groaned and tried to roll back toward the wall, where a patch of wattle showed through the mud plaster.

“Pearl, wake now.”

“I don’t care for him,” I murmured. “He tried to keep you from me.”

“Forgive him now, Pearl. We must forgive if we are to be forgiven. And besides, the messenger said it is Governor Winthrop who strives tonight for Heaven, not Governor Bellingham.”

“No,” I pouted, and resisted her efforts to roll me back toward her.

“Up, naughty girl, or I will leave you here alone in the dark for the Indians.”

That got me, and I sat with a sigh and let her rattle me. My forehead against her warm neck, I went limp and breathed my mother’s familiar scent. I felt the relief of her slowing heart. Languid as a little girl, I let her pull a dress on over my shift, tug and crimp and impatiently adjust me as if I were a piece of her embroidery. Entertaining a drowsy memory of my latest sampler, I remembered my promise to complete it before the Sabbath.

As she brushed my hair and pinned it back, I marveled at how my eyes adjusted to utter darkness. There seemed no moon tonight whatever, yet when Mother bent to wipe my face with her handkerchief I saw before me the scarlet letter that was my own birthmark, and floating above it Mother’s pale moonlike face.

“Aren’t you afraid?” I asked.

“No, Pearl.”

“Will the witches be out flying? Will Mistress Tibbins in her headdress watch us from the trees?” Mother smiled a distant smile and took my hand. She lifted her small sewing basket and we set out into the night.

“Why do you bring the basket?”

“To take his measure for a robe.”

I roamed ahead, though not far. It was the blackest night I had ever seen, with clouds thick above and fog ahead of me. I felt a strange thrill at the way the weather held the world in a damp embrace. How easily, I thought, the familiar might bleed into that other, olden faery world. Mother took back my hand as we moved through the sleeping streets, perhaps to calm herself. Though it was hard to see beyond the nearest dwelling or fencepost, I made Mother pause as we passed the scaffold, but she only yanked me forward.

“Tell me again—”

“No,” she hissed, and we kept going. “No, Pearl. I am weary of sad stories. Ask me for a happy one.”

I thought and thought about her command as we passed the residence of Governor Bellingham, who was not dying. His gabled house was dark and still, like most others, though for a moment I thought I saw a flicker of light beyond the casements. We spoke not another word as we traveled through fog and silence to Governor Winthrop’s stately home, where a servant let us in and took our cloaks. Looking at me, she raised her forefinger to her lips and with stern gaze gestured to a high-backed chair by the door. Mother nodded and bowed her head, and I sat down.

Wide awake now, I could scarce keep still in the dark as they went upstairs with the lantern. I sat on that chair surrounded by the shadowy objects of a powerful magistrate. I sat on my hands, listening hard to myriad footfalls and murmuring above.

As it often did, my mind wandered to Simon, who would be asleep now under the gaze of his carved figures. I imagined those sentinels springing to life one by one, stretching their crooked little limbs and stooping to peer on his sleep. Movement on the creaking wooden stairs startled me out of my reverie, and the servant appeared again, guiding the venerable Reverend Mr. Wilson, who must have been watching with the others at the sick man’s bed. While the girl went for the minister’s cloak, he tipped his hat to me, a dim smile flickering on his grave old face with its white beard, which seemed to register too well my presence, and I struggled to keep my feet still under the chair. I hardly drew breath until the servant returned with the cloak and a second lighted lantern.

Then a terrible shriek cut the night, a strange half-human sound unlike any I had heard before, not wolf or even the din I imagined witches making deep in the forest where they danced for the prince’s pleasure. It was far distant, but all three in the room stiffened, wild-eyed a moment, and looked to each other for assurance.

“Is it the fiend?” I asked sincerely, and the reverend with pinched lips squeezed my shoulder to silence me.

“Pray not, child.” He ducked out the door, bowing his head, his monstrous shadow flickering with the moving lantern. The serving girl leaned full against the wood when he’d gone and met my eyes. We shared a nervous, fleeting smile, and then she disappeared into a far room.

And did not return. Nor did Mother, though I heard from time to time the grating of chair legs on the floor upstairs. At length I slid off my own chair and paced the hearth room. I paced and let fear tempt me to the door. I went through it, out into the cool mist, easing the door softly shut behind, padding off with pounding heart in the direction whence the noise had issued, not because I wasn’t afraid but because I was and would know to whom the devil beckoned. I would see them sign his book, glimpse the bloody bread he would lay on tongues as black and bloated as eels. I would know who they were, which goodmen and women all of whom reviled me would answer his call, coming to him through the night, leaving behind their beds and Bibles.

Compelled onward by the horror of my thoughts, I became gradually conscious of the strange sensation of blindness. I even closed my eyes to block out the dim red-gray glow of the sky and to feel completely what Simon felt always. I let my ears guide me, fascinated by the story they and my other senses told me. My own heartbeat was louder than all else. I’d never pitied Simon and didn’t now, but I knew perhaps for the first time why the pace of his world must be slower than my own.

As I neared the scaffold—I knew the sharp slant downhill into the clearing beyond Governor Bellingham’s house—I heard the eerie, muffled sound of male laughter. It was furtive and cold and cut me out of my shallow blindness. I opened my eyes to a shock of red sky, to what I would later learn was the glow of a meteor. Freezing on my feet, I saw in the faint light a figure looming on the scaffold. It babbled and lurched, and soundless though I was, it turned and looked right at me.

“Pearl,” it said in rapt surprise, “did you hear me calling in your thoughts?”

I neither spoke nor nodded but stared. Had I heard him in my thoughts? And what could such a summons mean? Shame fogged my vision.

How quick he was. Before I could commence blubbering, he was at my side and kneeling; his arm, the one that didn’t have a bottle affixed to its end, had braced my slight shoulders. He smelled of spirits and tobacco and leathery male sweat, but also, faintly, lemon verbena or some other sweet herb. He hauled me close so I was smothered in his shirt, the same white linen, now soiled, he had worn on the day he gifted me with a feather in the field. “There, there, pip. Don’t squeak so. You’ll wake the town, and I’ll be slapped in the stocks come Sabbath day with every unruly servant, wife beater, blasphemer, ballad singer, and hedge tearer from here to Salem Town.”

“Sir,” I gasped, “you’re squeezing me.”

He pushed me lightly away with his free palm and took a drink that dribbled down his collar. “What business have you here in the black of night—” He tipped gamely toward me but righted himself—“with the devil for company?”

My feet would back away, but I forbade them. “Are you the devil—truly?”

“I am one soul in the world that knows you.”

“Are you the prince of Hell?” Persisting was a thing I did exceedingly well.

“Would that I knew the truth, Pearl, so that I could lie to you. No, not a prince—just a man.”

“A drunkard?”

Little impressed with youthful insight, Dr. Devlin took another swig, and the lines deepened round his eyes. “Is your mother there, Pearl?” His black brow peaked. “Hidden in your palm or under your bonnet? Is she there?” He caught me again and tried to steal a look under my cap, but when I flinched and brushed his hand away, real concern dawned in his eyes. “Settle down. I don’t bite. Why are you not in your bed, girl? What brings you out—here of all places?”

His doleful expression charmed a bit of charity from me. I smiled, and the smiling made me bold. “What brings you here?”

“Do you always favor a question with a question? I confess you bring me. She does. And the night air—and this scaffold. I’ve been studying the nail heads in the wood, Pearl. Know you that once, when herbs and bloodletting failed a patient of mine, one dear to me, I found my head empty of all wisdom imbibed at the Royal College.” His words came racing now, and I could scarce keep up with them. “An old method for curing ague says to situate yourself at a crossroads at midnight, and that is precisely where I found myself. Turn three times—so the wisdom goes—whilst driving a fair-sized nail into the ground up to the head. Then walk backward from it before the clock completes the twelfth stroke, and voila, the fever is expelled, moving instead to whosoever next steps on the nail. And what of the hapless soul who earns the ague, you ask?” He caught his breath in a sigh. “What can it matter but that somebody does? All bindings are commodities, Pearl. All life is barter. This sturdy scaffold: you have stood upon it—you know it? Or rather, your mother has—with you in tow.”

“For three long hours,” I put in, perhaps too willingly. “Her arms quaked holding me. The governor and his men frowned down on us from the meeting-house gallery.”

“Now, that’s the sort of morsel I crave, Pearl, as I patiently haunt my side of the line. We had a bargain, after all, but you’ve not returned to honor it. Have you another morsel for me? I would know you, Pearl. I would watch your mother walk these muddy roadways year after vanished year. How has she suffered? Where might she pause at market? Who will ease her day’s burden with a smile?”

“Spit on her hem, more like,” I murmured, cross that his talk had turned from me to my parent, who had, in my opinion, earned no such trifle.

He settled on a creaking step of the scaffold to urge me on, oblivious. “I hear, for instance, that you own the prettiest dresses in Boston. And that your mother flits to the dying like a moth to flame.”

“She tends the sick.”

He nodded agreeably. “She has a healer’s hands, but without hope to guide them.”

“Tonight she watches at the governor’s bedside. She’ll help the servants and have his measure for a robe.”

He looked up. “And how are you here by yourself? You should go at once before you’re missed.”

“You haven’t paid me yet.”

He surveyed me dully.

“All life is barter,” I reminded him.

The doctor felt in his pockets, sighing as he searched, and his bottle made a soft thunk in the grass. Because he came up empty-handed time and again, and because it seemed to pain him, I saw fit to give him more chatter. I told in a soft voice of my mother’s watch at the governor’s deathbed, of how tonight I’d crept up the stairs (but once) and heard her speaking to the doomed worthy almost as she spoke to me, in a mother’s voice. (Had the presence of Death made him a puling baby, then?) I told of my unfinished sampler and her matchless embroidery (she would not make pretty that savage emblem at her breast, though I begged her to decorate it and spite them all), of Eden and the coiled serpent, of brushing Mother’s long hair in the coppery twilight. I told of her lilting voice and the ever-fresh supply of impromptu lullabies that came like salmon from the rivers, slippery gifts from another world. I withheld her early effort to drown and be quit of me (this lives like a sore under my tongue, and I never air it), but I did describe her sporadic witless days and nights. I told how her strength seeped away and her neck seemed broken and how, at such times, I had to rouse and dress her, though her glazed eyes were Hell’s windows. I told of things lately on my mind, mine alone, of Simon and his princely brother, of stones hailing as I outran the resident holy pygmies, of the lure of the forest.

At last, slowly, he drew his pockets out and left them hanging linty for me. He pressed three warm fingertips to my runaway mouth and bade me stop, for he swore his heart was breaking, and it vexed him. “I have only a bitter, small specimen, Pearl, but you will have it in pieces. Let me repay you now, and we’ll resume our game in a more fitting time and place.” He paused to consider. “I have neither feather nor coin to offer, but you’ve heard of the great city of London?”

I nodded. Of course I had. What mooncalf hadn’t?

“You know it’s a vast stage, then, with all and sundry calling ‘Show!’ night and day, even under the offended nose of Cromwell. This you may know, but have your deprived ears heard of Bartholomew’s Fair at Smithfield?”

I sank to the night-moist grass in a willing heap, parked elbows on my knees, and gazed up at him. He paced the scaffold as if it were a wooden balcony from which a painted sign emblazoned with the words “Show! Show! Show!” hung. “A fair, sir? I have heard of them. We have none in Boston, though Election Day is nearly—”

“Of course you don’t, which is why I propose this as your due. Imagine a full fortnight of puppet-plays and hobbyhorses. Can you do that, Pearl?”

I nodded eagerly. He leaned close and I smelled the bottle on him, a heavy sweetness.

“As you step upon the grounds, you hear first the criers: ‘What do you lack?’ and ‘What is it you buy?’ And it unfurls at you like a great banner of brilliant color and sound and motion: wooden stalls adorned with gingerbread and mousetraps, theatrical booths and toy shops, pantomime operas and masquerading beggars, street performers, human freaks—”

“Freaks, sir?”

“Such as the girl of sixteen years, born in Cheshire, no more than eighteen inches high though she can whistle like a seven-foot sailor. Or the Giant Man, or the man with one head and two bodies, or the Little Faery Woman. Or, best of all, the man who can put any bone or vertebrae in his body out of joint and back again. And the animals, Pearl! As freaks go, witness the famed Horse and no Horse, whose tail stands where his head should do. Find puppies and ponies and whistling birds for sale, and join the swarming children who scour the ground for apple cores to feed the bears. For these bears dance, Pearl. What’s more there are performing dogs, peep shows, acrobats, dwarves, conjurers, and waxworks. There are pickpockets to spare, and mountebanks hawking rare and curious potions. There are canvas tents to dance and drink in, eating houses where you’ll find the most succulent roast pork imaginable. There is a symphony of ballad cries, drums, rattles, and bagpipes, and not least a rope walker who dares the journey with a duck on his head and a wheelbarrow before him containing two droop-eyed children and an Irish wolfhound. In short, there is spectacle, Pearl, living and breathing—and apprentice, lord, and milkmaid enjoy it together. Now,” he said wearily, for his bottle was drained, and with the dream of the fair receding he seemed as bereft as I knew I would be when he sent me away, which he promptly did, “go back where your mother set you down. Or rather,” he added abruptly, “first—come up here a moment.”

I stood my ground.

“You’ve been before,” he explained solemnly, “you and your mother both, but your father was not with you. Come, and I will stand on his behalf, and we will step forth in spirit, all three together.”

Daniel Devlin staggered up the scaffold steps. I felt, in the face of his evident lunacy, a throbbing in my chest and ears, and at length I understood that it was not lunacy but some bitter truth that plagued him. His face seemed distorted, and his eyes shone as he backtracked, fumbling for my free hand.

A voice that came from me but seemed not mine whispered, “Sir?”

He looked straight through me, and I shuddered. “Come, Pearl. I have tarried long with ghosts. Take my hand.”

“Will you bring him? Will he stand with Mother and me tomorrow noontide?” I was riveted by the sight of a shadowy figure across the way that for a moment I mistook for the very fiend whose name was bandied about Boston like hayseed (he must be out here somewhere, my father), come to witness our vigil. But it was only the minister, out from the parsonage in his nightshirt, as pale and wasted in appearance as I’d seen him. “Pearl,” he barked, “step down from there at once. Away from that man—”

“Why confound her more, Arthur?” came the doctor’s slurred demand.

I might have guessed that the minister would brim with pity, and I tried to shut out his whispered rhetoric by focusing on the quiet of the surrounding night. Unlike the last time we three had stood together—near Mistress Weary’s grave—it was the minister’s tone that seethed with a malice of consolation. But I soon succeeded in not hearing him at all. I smiled outright at the astonishing pair the doctor and I made on the scaffold, in full view of the good but useless minister in his nightshirt. At length I began to giggle uncontrollably, even as the poor appalled man of God came stamping up the steps to clasp my wayward arm—and Daniel Devlin transcended his tippling to leap from the platform like a cougar, to vanish into the gracious dark, laughing also, like the terrible villain I would one day discover he was.

I wonder now, years later, what else he might have done, which action—relent confess apologize grovel demur—would not have seemed preposterous, or pointless, or false. Leaving is as close to grace as some of us will come.

It was not many days later that Mother and I happened upon our minister on a secluded stretch of beach. So many strange things had happened, were happening, that I thought little of it when Mother shooed me (and due modesty) away and rushed to speak with him.

The night I stood with Dr. Devlin on the scaffold, the minister had at first remained a long, strange while across the way, as if we two were in fact players on a stage in the fog and not people he knew. At last he crossed to us, and his words, sharp at first, gradually soothed the doctor’s ravings. He spoke of the dangers of a life of the mind, of a life lived in books, of a reality blurred with dreaming by day and tippling by night. He seemed to know well the doctor’s plight. As the man of God paused for thought, the physician began to look cornered. The devil came into his eyes, and he leapt.

I had slept poorly many days since, with the doctor leaping and leaping through my thoughts: wicked and foolish he seemed, pitiable and dangerous. On this afternoon when Mother and I met the minister out walking at the shore, I wandered drowsily in the tide, digging a stick in the sandy pools and chattering to my reflection. I dragged my bare feet along the packed sand and amused myself by scrawling Simon’s name in giant letters for the gulls to read. I had gone to him the day after the infamy on the scaffold but found only the empty garden. I had leaned against the beech and watched the new kitchen greens wave in a gentle breeze, feeling as bleak and hollow as I ever would.

Despite my efforts to conjure Simon now and hold him in view, it was the doctor’s face that stayed as my mind churned over and over his strange words on the scaffold: Did you hear me calling in your thoughts? I am one soul in the world that knows you.

I watched with grim resignation as the tide washed my handiwork away. S-I-M-O-N. I chanted the letters over and over, watching from the corner of my eye Mother’s agitated stance. It was, of course, the physician they spoke of. The minister’s earnest voice came like waves: My finger, pointed at this man, would have hurled him into a dungeon once . . . . I thought to let him lodge with me that I might coax him toward a public confession . . . such splendor in a man lost . . . . His words scattered like gulls on the wind. I have offered and offer still to assist you . . . . though it be too late to invoke the law it is not too late to clear your name . . . . Away on the wind. Wind and tide, stink of fish . . . magistrates . . . He would have you accuse him! He taunts me, knowing you will not . . . . Does he pity those who loved him once?

Mother’s proud hands gestured at the air, and they were two bodies drawn together in the ocean’s roar, their words churned and muted. It was a strange, unsettling dance, for it reminded me again of how little I knew and how much the world kept from me. Mother held her back very straight. She blazed with purpose, and the beloved face, the lips that kissed me each night but now spoke coldly to our only friend and counsel—dull and ineffectual though he sometimes was—looked not familiar. He has seen Pearl, you know. Do you know? Look at me, please. Hear me . . . he speaks of her . . . to her as to a familiar . . . he harps on your brand. The minister cast down his eyes at mention of the careworn “A” at my mother’s breast.

Mother glared out to sea, as if the sea itself had failed her.

Furtive as a cat but I think he does wish at last to wear the stain that is his alone to bear . . . and I can in conscience only give him leave to speak it if I might act on behalf of right . . . cannot it seems find courage to set right his soul nor forsake earthly fear. You can be just and publicly accuse him . . . for the child’s sake if not your own . . . .

What will she gain, Mother countered, seeing the old sore ripped open? I tore across the beach holding my skirts high. The child. The child. A sickening word, really—child—helpless as a snail, but it set me spinning and whirling in the sun. I kicked at the water’s white foam to send it flying. I played a lunatic in hopes of distracting them from their passionate debate, but they never once looked at me. Is pity easier to bear than scorn, minister? I think not—for my child. Mother shook her head. Her stern air dissolved in tears.

The child turned to other live creatures to assure herself that she was there at all. She poked at a horseshoe crab, collected starfish in a line, and even laid out a jellyfish to melt in the sun. He will not go until he has what he came for. We must ask what that thing is . . . the simple if lamentable alternative is to go. Travel as you’ve dreamed to your mother’s people in Leiden.

At length, frustration throbbing in my ears, I gathered pebbles into my apron and took to pelting the rigid, hopping sandpipers, outside myself. I wasn’t really trying to hit them, but I injured the wing of one little bird and felt a sinking dread as it bounded away. I spilled my stash of pebbles to the ground and stared at my hands but could not recognize them.

Watching Mother from this distance, I saw the dull letter at her breast. The sun made a mockery of it, and I was inspired to craft a lovelier version from eelgrass, and to plaster it on my own budding chest. I twirled and preened and vaguely heard Mother, closer now, calling me. I looked up in time to see the minister stride away, but I was too consumed by the artful “A” on my dress to pay him much mind. At length Mother came and exclaimed at my damp garb, and made as if to brush away my weedy costume. I darted out of her reach.

“Pearl,” she said, almost gently, “that sign is not yours to bear.”

I pursed my lips and let the words slip free. “‘A’ is for apple.” I watched carefully to see what reception this pronouncement—this challenge—might find.

Her eyes for an instant’s glimmer seemed to consider me in a new and more serious light, despite my sodden dress, but quickly grew distant again.

“‘A’ is for almond,” I went on in the dull, unquestioning tone usually reserved for Dame Ashley. “Angel, alabaster, able—”

“Adultery,” Mother sighed heavily. “As well you know. And to do with no heart save mine.”

No heart, indeed. I wanted to lunge at her and knock her down. I wanted to weep and be comforted, to shriek and claw at her, but instead I stood barefoot in the sand, soothed by the vastness of the sea. Our lives could be small there, and I could take comfort in the whispering tide. I ripped the seaweed from my dress and wrung it like a cloth, watching what little water remained drizzle over my narrow wrists.

Brushing away tears she had been too rigid to touch, Mother turned and set off without a word. I followed with one last pensive look at the sea. Mastered by some dim need to torment her, I trailed and taunted all that evening as we walked, supped, and readied ourselves for sleep. No heart save mine, no heart save mine, no heart save mine. “A” is for arse and ale and alchemy and anarchy and ashes to ashes and atheist and Anabaptist . . . . What, pray, is the name of my father? To this last, she answered as she always did but with barely contained rage and anguish: “You share the same Father we all do.”

By bedtime, she had threatened to shut me and my treacherous blasphemies in the closet.

Even after she had tucked me in and kissed my brow, thinking me asleep, I felt mischief surging and let my eyes spring open. My voice rose from my startled throat, and Mother fairly leapt out of her skin. “‘A’ is for absent—”

She placed her cool hand over my mouth, sternly, and shook her head. “Sleep now, Pearl.”