Читать книгу My Japanese Table - Debra Samuels - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

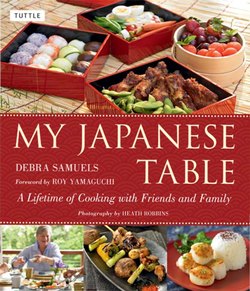

ОглавлениеA Lifetime of Cooking Japanese Food with Family and Friends

My taste buds and I came of age together in Japan. In the early 1970s, when I was twenty and just married, my husband, Dick and I arrived in Japan for a semester abroad. Although we had studied Japan and Japanese, we knew nothing of the cuisine. Just like love, there is a first time for everything, and so on our first visit to a Japanese home we were offered a traditional bath and sashimi (in that order)—neither of which we had ever experienced and neither of which we could possibly refuse. Still wet from the bath, we were directed to a low table with a kaleidoscopic platter of gleaming raw fish. Nothing had prepared me for this; I was horrified by the very idea of raw fish—but there was no polite way out. Our smiling hosts watched eagerly as I took my awkward first bite and, sure enough, I could barely swallow the slippery repast. I like to believe that somehow I managed not to embarrass myself or them.

After further language study, our next stop was a home-stay in the port town of Tsukumi, in rural Kyushu. We lived at the home of a physician, Dr. Chikanori Oishi (Oishi Sensei) and his 15-year-old son Shingo (Shingo’s brother, Seichiro, and sister, Eriko were away at university). As is common among Japanese doctors, the doctor’s home was also a small hospital, with beds for patients. Ordinarily, the doctor’s wife would run the home, but Shingo’s mother had died the year before, so a small staff of nurses and a housekeeper looked after the patients, the doctor, his son, and now us. Each day we awoke to the smell of miso soup, steamed rice, and roasted fish. I hung around the kitchen and helped the staff prepare the lunches. The aromas in that home remain imprinted on my senses today and are strongest when I prepare the basic Classic Miso Soup you will find on page 81.

After graduation, my husband began his graduate studies, and his field research brought us back to Japan in the late 1970s with our then 5-month-old son, Brad. For 2 1/2 years we lived in a tall gray concrete apartment complex in a working class Tokyo neighborhood. Our apartment was spare—two small tatami mat rooms with a kitchen/dining area. We slept on a futon, Japanese style—Brad in between us—which I folded up and stored away every morning. Our small washing machine was outdoors on our tiny cement terrace, and my kitchen was a six-foot counter with a 2-burner stove top and a toaster oven. The fridge was “dorm room” size, so like all my neighbors, I shopped daily. Dick, who is 6’4” (193 cm) felt cramped, but I was thrilled. He began a lifetime of banging his head against low doorways and ceilings, while at 5 feet tall, everything was in arm’s reach for me. In downtown Tokyo my taste buds were educated by my kind neighbors and, after a while, more formally when I enrolled in classes to learn Japanese homestyle (katei) cooking.

The famous Tsukiji fish market was just across the Sumida River, which ran next to our apartment building. Our neighbors there adopted us. No one spoke English and my Japanese was still tentative. I would not have survived but for the “kindness of these strangers.” I have never forgotten how they embraced our family, and I have spent the rest of my life trying to reciprocate by helping others who find themselves in similar situations. As I settled into the rhythms of Japanese life, I began looking forward to the sound of the tofu vendor’s horn on his bicycle, to the rhythmic call of the roasted sweet potato hawker in his rickety truck, and to the daily banter with the local shopkeepers. My love affair with Japanese food was well underway. Daily shopping made me appreciate serving the freshest food possible. Each new ingredient provided an opportunity for mini cooking lessons with my neighbors. They showed me how to put together a chicken hot pot (mizutaki) and lent me the clay pot (donabe) to do it. I learned how to rinse short grain rice until the freezing cold water ran clear or my reddened hands seized up.

Half way through our stay we moved from downtown Tokyo to the suburbs. Brad went to Japanese nursery school, I went to work, and Dick finished his dissertation. We returned to the States with a three-year-old and a baby on the way.

In the mid-1980s we returned to Japan when Dick began research for a new book. Now we had two boys in tow—Brad was 6 and Alex was 3. I marketed daily at the small shops in Hamadayama, a Tokyo suburb. My bicycle had a grocery basket in the front and a seat for Alex in the back. With him perched on his little throne, we would cruise up and down the high street, buying ingredients for dinner. Alex quickly became fluent in Japanese and soon knew that the locals found him different and cute (kawaii). He was quick enough to know that if he said “ oishii-sō ” (that looks so yummy!) while staring directly at a mountain of just-fried chicken, the granny behind the counter would offer him a crispy piece. Then he would bow and say “ domo ” (thanks), and out would come another one! The kid had his routine perfected, and by the time we were on the way home he was full.

Brad was a first grader at the local elementary school, so I learned to prepare Japanese-style boxed lunch (bento) for him. These box lunches were culinary masterpieces—at least when in the ways the other moms prepared them. Brad made it clear that American-style peanut butter and jelly sandwiches in a brown paper bag just wouldn’t do! Far from thinking these moms were mad to be spending an hour preparing cute lunches for their kids, I embraced the idea. I bought myself a Japanese book called 100 Obento Ideas and a little blue plastic bento box in the shape of a car for Brad. For the rest of the school year I made my way through that book, letting him pick his lunches by looking at the pictures. Maybe I was mad too, but he always finished his lunches.

This was also when I started taking Japanese cooking classes at the home of Michiko Odagiri, an elegant and well-known cooking teacher who, like Julia Child, taught cooking on Japan’s public television network, NHK. Her class was aimed at Japanese women, and I was the only foreigner in attendance. I could understand her oral instructions, but her recipes were written in Japanese, which I had not fully mastered. Fortunately, my fellow students read the recipes to me after each class, and I translated and transcribed them into my notebook. These recipes formed the base of my practical training, and many appear in some form in this cookbook with the kind permission of Odagiri Sensei’s daughter Shigeko.

Here is where I learned to make Dashi (Fish Stock) (p. 35), my first sushi roll, and the delicate sanbaizu vinegar dressing. The first class I spent on knife skills cutting paper-thin slices of ginger. Another was spent separating the whites and yolks from hard-boiled eggs and then pressing them through a wire mesh tool that acted as a ricer, to create a decorative flower garnish. The attention to detail was paramount. How would I ever keep this up?

About that same time, I bought The Simple Art of Japanese Cooking by Shizuo Tsuji, first published in 1983 by Kodansha International. It was, and in my opinion still is, the go to reference on standard Japanese cuisine. It just was revised and re-issued in 2008.

We left Japan after another year. By now I had a solid technical base in Japanese cuisine. I began teaching and doing workshops upon my return to Boston.

We returned again in the 90’s for another of Dick’s book projects and this time I spent a year learning the food of everyday meals: Chicken and Egg Rice Bowl (Oyako Donburi), our favorite Stuffed Savory Pancake (Okonomiyaki), Chunky Miso Chowder (Tonjiru). Brad and Alex were now middle and high school students.

By the time Dick and I celebrated our 30th wedding anniversary, we had lived in Japan on and off for nearly a decade. We marked the occasion at a hot spring onsen in the mountains of Nagano known for its healing waters, its elegant pottery, and its amazing food. Each meal was designed to mirror nature in miniature—each morsel was a delight and each dish was exquisite. One memorable dish was a small roasted trout, set upon a dish resembling a river and looking as though it had paused midstream. We reflected on the arc of our life in Japan together. Our sons had been in nursery, elementary, and high school in Japan, and we had lived all over the Tokyo metropolitan area, as well as in Kyoto and Kyushu. Japan had long since become our second home. With each decade that passed I had a new persona in Japan. In the early 1970s, the neighborhood kids called me oneesan (elder sister); a decade later I had become “ Buraado-kun to Arekisu-kun no okaasan (Brad and Alex’s mom); by the 1990s I was Debi obasan (Auntie Debbie). These days my friends in Japan all ask if I am an obaachan (grandmother) yet.

All that reminiscing brought us back to the ways in which Japanese foods and aesthetics are not solely the domain of elegant and isolated retreats. It is often said that in Japan “one eats with one’s eyes,” and that every customer is an “honored guest” (okyakusama). Quality and presentation of the food are important, even in prepared foods in supermarkets and urban convenience stores. Slices of tuna atop a bed of shredded white daikon radish with a perfect pinch of grated ginger—placed just-off-center—are thoughtfully designed for take out at even the most unassuming market.

Nor is Japanese food just a matter of daily consumption; it is also about gift giving. Most department store basements (depachika) have two levels, one entirely devoted to food for gift giving. Railway stations across the country offer themed, regional specialties in the form of “station box lunches” (eki-ben). Some are consumed on the trip and others are brought along as gifts for fortunate friends and relatives. But their passions embrace more than just their native cuisine.

Japan has been adapting foreign cuisines to local tastes and sensibilities for centuries. Many dishes that originated abroad are now part of the repertoire of both home cooks and restaurants alike: Curry rice, originally from South Asia; ramen, gyoza, shumai, noodles and dumplings from China; yakiniku barbecue beef and spicy pol-lock roe mentaiko from Korea; deep fried tonkatsu cutlets and tempura from Portugal; and pasta from Italy are all now thoroughly standard Japanese meals in homes across the archipelago.

Conversely, the rest of the world has discovered and embraced Japanese food. Sushi and ramen are staples in supermarkets in North America and Western Europe; tofu no longer terrifies Western consumers; and words like edamame, teriyaki, and wasabi no longer need translation or italics.

I saw the embrace of Japanese cuisine in my own family. As soon as they could express their preferences, my sons asked for octopus (tako) and seaweed (nori) instead of steak and mashed potatoes. They may have had a head start, but they certainly are not alone. Today, American kids do not need to wait an entire lifetime to educate their palates. Instead of a pizza on a Friday night, ten-year-old kids ask for California rolls, a thoroughly American invention that has made its way back over the Pacific. Many opt to snack on edamame in instead of potato chips. I have been teaching my nephew, Brandon, how to make sushi rolls since he was eight, and every time I visit we make something new. He is now nearly twenty and has never been to Japan, but he recently begged me to teach him how to make “inside-out” rolls. Although not considered pure sushi by some, these American concoctions are as popular in Japan as “American” bagels are in Israel.

There are many sources for the recipes in this book. In addition to cooking and eating in my friends’ homes, I have been inspired by imaginative meals at Japanese pubs called izakaya. Here chefs offer small plates, like Spanish tapas, that match creatively styled fish, meat, and vegetables with beer, grape wines, rice-based sake, and (mostly) potato-based shochu. Other recipes come from festivals (matsuri) at Japan’s shrines and temples. Whether celebrating the harvest, the coming of the rains, school entrance examinations, or the appearance of spring blossoms, these festivals are celebrated with street food from itinerant vendors’ stalls featuring the savory and sweet snacks that form the core of millions of Japanese childhood memories.

And, given my sons’ experiences, how could I not include a chapter on box lunch bento? But bento is not just for kids. They have already caught on in the United States, and there are many instructional websites in English. You can purchase bento boxes on-line or seek out alternatives, as I will show you. These attractive, appropriately portioned, and nutritionally balanced boxed meals will be a boon to you and your family’s health.

In writing this book I have called upon a lifetime of experiences and upon a great many Japanese friends who have influenced my work (and play) in the kitchen. I hope it will appeal to experienced readers who already have an interest and knowledge about Japanese cuisine, as well as to beginners poised to discover all it has to offer. Many of the recipes are from classes I teach on Japanese home style cooking designed for students to achieve success on their own. My philosophy is that we should leave the fancy stuff to the pros (sushi chefs train for years for a reason). But you can still enjoy sushi and sashimi, served home style. Join me in the kitchen to discover some of my favorite Japanese recipes and it won’t take you a lifetime to learn them.

Teaching

Despite my degree in elementary education, I have been teaching everywhere but in a conventional classroom. My first job, as 4-H agricultural agent, took me right to the farm and exposed me to the fundamentals of canning, baking, and pickling.

But teaching about food started as an informal exchange with a group of four Japanese women whose husbands, like mine, were studying at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the mid-1970s. Masayo, from rural Shikoku, was the mom of a middle schooler; Emi was a Tokyo social worker; Harumi, from Yokohama, was interested in the Japanese arts of tea and kimono, and Yoshiko was a Tokyo office worker. We each started with the basics of our cuisines: I taught them how to bake bread and can jams, and they taught me how to make Japanese rice and rolled sushi. And so it was that when Dick and I returned to Tokyo to live for three years, I could navigate a market, recognize food labels, and guess what to do with the product.

My transition to formal teaching was gradual. It started with an English lesson in a supermarket for a Japanese mom with two kids back in Boston in the early 1980s. Supermarket English lessons evolved into tutorials on American food ingredients and eventually into American cooking lessons for groups of Japanese women. Along the way I was asked to teach classes on Japanese food and culture to American college students interested in Japan.

One thing always leads to another in life, and so it was with teaching and me. Between five subsequent yearlong stays in Japan that enabled my continuing education in Japanese cuisine (including formal classes in Japanese cooking), I started a catering business that I called “Eats Meets West” (pun intended) because there was now so much of Asia in my repertoire. Meanwhile, there was increasing demand for cooking classes on both Western and Japanese cuisine. In the early 1990s I began working in the Japan Program at the Boston Children’s Museum and offered teacher workshops about Japanese food and culture, often focusing on kids’ bento lunch boxes;

I have subsequently done similar programs in Boston, New York, Washington D.C., and Tokyo. While at the museum, I developed the “Kids Are Cooking” program, which focused on introducing children to a world of cuisines, cooking fundamentals, and nutrition. Writing about food and culture for The Boston Globe was a natural next step in my rather unconventional journey.

Debra Samuels