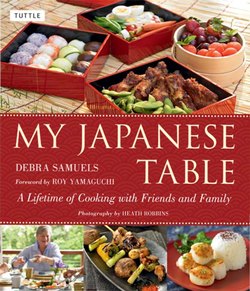

Читать книгу My Japanese Table - Debra Samuels - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThoughts About Japanese Cuisine

I do not have a Japanese mother or mother-in-law and I did not grow up with Japanese food, flavors, or cooking techniques. The only soy sauce I encountered had caramel food coloring and lots of salt. In fact, my dear mother, Rona Greenberg, did not react very well when I told her in 1977 that we would be going to Japan with her first grandchild. “But what will he eat?” she wailed. “Tofu,” I tossed out. This only made her cry harder. Who in suburban New York knew from tofu at that time—or much about Japanese food beyond the theater of knife twirling chefs in Japanese steak houses? Sure, the counter-culture set was dabbling in macrobiotic food with some Japanese roots, but we were still several years away from Japan’s emergence as a global economic power and from the Japanese culinary boom that followed. Thankfully, in the subsequent four decades I have had dozens and dozens of surrogate mothers, sisters, aunties, and certified teachers who took me under their collective wings. (Rona still won’t eat tofu, but she loves yakitori.)

My experience has distilled into a singular, powerful impression of how Japanese cooks—professionals and home cooks alike—respect the process, the product, and the details of a meal. They commit themselves to the highest quality of each and establish an aesthetic that appeals to every sense. Setting a perfect leaf just off center on a plate of sliced persimmon is for your eyes; pressing a hardboiled egg through the tight wire mesh of a ricer (uragoshi) produces a velvety texture for your tongue; twisting a yuzu peel for a burst of citrusy bouquet is for your nose. What may seem like small enhancements actually are the essence of the Japanese table. Each is second nature to the Japanese cook, and now, after decades, to me as well. Hopefully they will appeal to you too.

Like cooks everywhere, Japanese cooks have always been curious and innovative. Although tofu was introduced to Japan through China as early as 600 AD, it was the Buddhist monks and the aristocracy who mainly consumed it. It became part of the commoners’ diet in the 16th century. This was about the time when Portuguese merchants and clergy introduced deep fried pork (tonkatsu), deep fried fish and vegetables (tempura), and sweet pound cake (kasutera). French pastries became Japonaise after the Japanese themselves ventured out in the 19th and 20th centuries. And now, as the world eagerly embraces their cuisine, they are still absorbing new ingredients and adapting to a rapidly globalizing world food market. Take wafu (Japanese style) pasta for example. One version marries shredded seaweed with spaghetti and spicy pollack roe (mentaiko). This is actually a “two-fer”—the pasta is from Italy and the spicy roe is from Korea. The novelty of putting it all together is purely Japanese.

So, what are the elements that make food Japanese? In Italy, one encounters alio (garlic), olio (olive oil), and prezzemolo (parsley) in most dishes. Korean cuisine features pa (scallions), manul (garlic), and chamgirum (sesame oil). Japanese cuisine also has its own distinctive flavor profile found in its seasonings (chomiryo). Sa, shi, su, se, so () is a line of sounds in the Japanese hiragana syllabary that captures many of the essential elements and the order of the seasonings of a Japanese dish. Sato is sugar; Shio is salt; Su is vinegar; Seiyo is an old fashioned word for soy sauce; and Miso is fermented bean paste. But there are five more seasonings: mirin (sweet rice wine), sake (rice wine), kelp (kombu), dried shiitake mushrooms; and dried katsuo (bonito used to make fish stock), and you have a palette of Japanese flavors. Sugars and alcohol (mirin and sake) are added in the beginning to flavor and cook down the alcohol content, and strong seasonings like soy sauce and miso come later to maintain maximum flavor.

These days the word umami, commonly referred to as the savory fifth taste, is on everyone’s tongue. Umami was identified by a Japanese scientist a century ago and occurs naturally in kelp (kombu), mushrooms, and fermented foods like soy sauce, miso, and Dashi (Fish Stock). The chemical base of umami, glutamates, is synthesized in MSG through a fermentation process. Some people have sensitivity to MSG, but in moderate amounts this flavor enhancer has not proven to be harmful.

Japanese cuisine has five important elements: seasonality, presentation, quality, portion size, and balance. Flavors peak and different local foods are available at different times of the year, so the season often dictates restaurant and recipe choices. The first bamboo shoots of the spring are eagerly anticipated for adding to rice (takenoko gohan). Eel (unagi) is fresh and abundant in the summer, when its rejuvenating powers are especially appreciated. This is also the season for cold noodles in refreshing light vinaigrettes. In the autumn, the long, silver-bodied Pacific saury (sanma) are grilled simply with salt (shioyaki) and meals are finished with giant, thick-skinned, purple-blue grapes. Daikon radishes are sweetest in the winter, when hot pots with bubbling stocks are favorite communal dishes. The season not only influences the choice of food, but also the tableware. Earthy fall and winter pottery often give way to decorative porcelain and glass in the spring and summer.

This relationship of vessel and food is captured by the Japanese expression that one eats with one’s eyes (me de taberu). This aesthetic is not reserved just for gift food, like handsomely wrapped Japanese sweets (wagashi) or high-end formal meals, with their multiple, gorgeously arranged dishes. It is also incorporated into the most routine fare: takeout from a convenience store so thoughtfully constructed that you'll forget it was mass produced; bento box lunches that entice you to eat every last bite; even the garnish of contrasting colors on the home dinner plate. The Japanese culinary aesthetic is spare. Odd numbers of dishes are often arranged in asymmetric patterns. A thin green chive blade will set off the flesh of a single plump and perfect scallop. A square of grilled tofu is topped by thinly spread miso with a sprinkling of poppy seeds. Not all Japanese meals are elegant and minimalist, but most are appetizing. Brimming bowls of hot ramen and spicy curry rice—two of the most modest and popular meals—and feathery mounds of bonito flakes atop a Stuffed Savory Pancake (Okonomiyaki) are always presented in an appealing way.

Food is expensive in Japan, and Japanese consumers do not shy away from spending a large potion of their budget for high quality ingredients. Everyone has heard of the pampered cows that produce the famous, highly marbled Kobe beef (wagyū), and of the meticulously tended vines that produce intensely sweet (and expensive) melons. This insistence on high quality, labor-intensive production extends to prepared foods as well. All major department stores have food emporia, usually in their basement, where shoppers can see their food prepared, cooked, and packaged. The tofu makers on the premises use clear running water and the pleated dumpling crafters scoop freshly prepared fillings into thin, hand cut wrappers. A great deal of labor goes into Japan’s love for high quality food, and they have little tolerance for sloppiness. One way to maintain access to high quality food within a household budget is to reduce the volume, a tactic that fits naturally with the emphasis on smaller portion sizes.

Portion sizes for most meals served in Japan are small to moderate by western standards. It is rare that one plate will hold an entire Japanese-style meal. Portions are dictated by the size of the plates on which they are individually served, and most meals feature multiple small plates, none of which is intended to overwhelm the others. Side dishes (okazu) each make a distinctive contribution to the meal and these vegetables, soups, and pickles are not mixed together. The main protein, such as a piece of grilled fish, is typically less than 4 ounces (100 g). Formal presentation of a meal is usually done on a lacquer tray. Even this relatively austere practice incorporates each of the central elements of a Japanese meal, including balance.

Japanese meals are balanced in many ways, from cosmology to cooking techniques. The oldest balancing act comes through Chinese beliefs about interaction among five components: wood, fire, earth, metal and water; their corresponding colors: green, red, yellow, white, and black—each of which corresponds to organs in the body; and their corresponding tastes: bitter, salty, sour, sweet and savory. Whether consciously or not, most Japanese cooks use these concepts to guide their menus and enhance well being. A formal meal also balances cooking methods, and will include items that are stir-fried (yaitamono), simmered (nimono), deep-fried (agemono), grilled (yakimono), and steamed (mushimono). The Japanese diet is also balanced by a rich variety of fermented foods that are eaten daily in some form. Miso, soy sauce, fermented soy beans (natto), and pickles (tsukemono) all have distinct health benefits, work as appetite enhancers, aid in digestion, are nutrient rich, and help balance the body’s chemistry.

Above all, the Japanese meal is balanced around rice. One of the many Japanese words for a meal is gohan, which also refers to cooked rice; indicating just how central rice is to the Japanese diet. Japanese rice is the short grain and medium grain japonica variety. Often called “sticky rice” outside Japan, it is different from the glutinous rice (mochigome) that the Japanese and other Asians refer to as sticky rice. Japanese rice farming has been heavily subsidized by the government and is one of the few foods that Japanese farmers produce in self-sustaining volume.

And, of course, Japan is an island nation that depends upon the ocean for much of its protein. Seafood is consumed in many forms: raw, dried, cooked, ground, and whole. Low in fat, high in omega fatty acids and calcium, fish is eaten in greater volume in Japan than beef, pork, and chicken combined. The sea is also a source of one of Japan’s most popular and nutritious vegetables: seaweed, which comes in staggering number of varieties. Used to make stocks, in salads, and to wrap around rice, seaweed is high in vitamins B and C and is a natural source of glutamates.

Japanese cuisine is far broader than rice and the ocean’s bounty. Noodles have their own food culture and are often a meal of their own. Buckwheat noodles (soba) are nutritious, chewy, and simple to prepare. Their thicker, white wheat-based cousin, udon, is popular in soups and hot pots. Ramen retains its Chinese influence and has reached cult-like status, while the thin angel hair threads of sōmen are served cold and minimally adorned. Noodle stocks can range from a Fish Stock-soy based broth, to the rich ramen soup made from a mixture of pork and beef bones, often with a chicken carcass thrown in for good measure.

Beef, pork and chicken are also used in main dishes, though in lesser quantities than in Western meals. Beef is often simmered in a sweet soy stock (sukiyaki), while pork is stir-fried with ginger (shogayaki) or enjoyed as deep-fried cutlets (tonkatsu). Chicken pieces are grilled on skewers (yakitori), deep fried (kara age), and simmered to make a topping for a rice bowl (oyako donburi). Tofu and tofu products are a prominent source of non-animal protein in soups, hot pots, salads, and dressings.

Every region and, it seems, every village, town, and city is justifiably proud of its specialty dishes (meibutsu). Fukuoka and Nagasaki are famous for their Chinese influenced noodles (chanpon), while Hokkaido, to the north, is known for its salmon hot pots. My friends from the Kansai region (Osaka and Kyoto) insist that their sukiyaki is special—they add the seasonings one-by-one instead of making a sauce and adding it all at once, as Tokyoites do. A stay in the mountains of Nagano yields trout (ayu) as well as dishes rich in wild vegetables and herbs (sansai), such as bracken (warabi) and fiddlehead ferns (zenmai). And the wild boar served in other mountain regions as a hot pot meal (botan nabe), is exquisitely arranged on a platter in the shape of a peony. Can you see that preparing and serving Japanese cuisine is a thoughtful endeavor? To me this is the essence of this cuisine. The details, the flavor combinations, the concentration on eating foods for well-being, and, above all, the consideration of presentation together make it special.

Putting together your own Japanese table will be easier than you might think. Most of the tableware photographed for this book is part of my own collection, and when I serve a full Japanese meal or teach a class, I always incorporate western dishware as well. In addition to embracing the idea that everything does not have to match, you also should downsize. The western dinner plate becomes a serving platter or tray, the salads plate for the main dish, and saucers and dessert plates are perfect for side dishes. I accent the table with Japanese bowls and condiment dishes, and I follow Japanese etiquette by placing chopsticks parallel to the front of the diner’s plate or bowl, with the tips pointing to the left, set on a chopstick rest. These functional rests also add decorative elegance to the table. Although napkins are not part of a Japanese place setting, I set rolled white organdy napkins with blue embroidered flowers from my Nana’s wedding trousseau just above the chopsticks. It’s these touches that make this my Japanese table, and now, using this book, I hope you will enjoy creating your own.