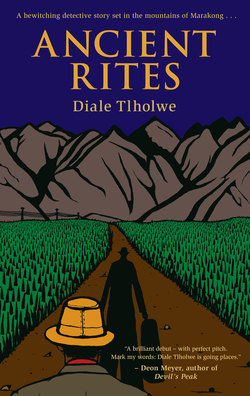

Читать книгу Ancient Rites - Diale Tlholwe - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 4

Chapter 4

There were two paths going to the school from the village above my cottage. The first came into the little valley and then rose again to the level ground on which the school stood. The second was much longer and skirted the hollow in a semicircle, approaching the school from the opposite direction after joining the road from Mafikeng.

Apparently the school children preferred the longer route. I had been up early, heated up old Ma Molefe’s food and made it my breakfast. I was sure that no one had passed my door, but they were all already in the school yard by the time I got there.

I had planned on arriving early, before eight, but the children had beaten me to it. And on a winter’s morning too. Incredible! My intention of poking around the school unsupervised was undone. I couldn’t do anything with so many little eyes recording my every step.

So I did what any new arrival would do. I headed for a familiar door. I had not even touched the Principal’s door knob when someone giggled behind me. I turned around to find a small boy standing there. A tiny shadow of a boy – and apparently also able to move just as silently as a shadow as well – he had the delicate features of the Khoisan.

He had a key in his hand and, extremely shyly, he gave it to me. He pointed at a door at the end of the row of prefabricated classrooms. I gave him a friendly pat on his head and what I hope was my best smile. He only thrust his finger at the door vigorously in reply and trotted towards it.

I followed him. “My name is . . .” I began as I reached him.

“You are Tichere Maje,” he said firmly, interrupting me.

This was not due to my all-conquering fame, or the boy’s supernatural powers. I should have known that by now everyone who had anything to do with the school would be in possession of my vital statistics. An invisible file had been opened on me. It would only be closed the day I left, and perhaps not even then if I did or said something amazingly novel during my stay.

“What’s your name?” I asked as he led me into the classroom.

“Jan-Jan Mothibi.”

As I watched him float away and join his friends in a scuffle about a ragged football, it came to me that he was possessed of that terrible fragility of a people staring into the abyss, with cold shadows gathering around their kind as their numbers diminished with every turning of the earth. I have seen that haunted, far-away look before and I was sure that I would see the same look again in the eyes of others before I left Marakong-a-Badimo. The look of a people who sensed that when humanity finally gathered around the last fire, they may be absent, their tongues long stilled and their last prayers unheard.

* * *

The classroom was very clean. In fact, I had never seen a cleaner classroom that was in regular use. The desks were arranged in precise rows. The best drilled soldiers could not have marched in a more orderly fashion. I sensed Mokoka’s influence.

A tall, athletic-looking girl of about twelve or thirteen entered while I stood, amazed, before the teacher’s cupboard. It was beyond my experience, this spinsterish neatness, in any classroom, especially one Mamorena had taught in. The reformation must have come after her disappearance. Unless . . . unless she herself had changed.

“Tichere Maje! The Principal wants you to come to the office,” the girl said in a clear Setswana voice.

Mokoka and his entourage had obviously arrived.

“Who looks after the classroom?” I asked, still slightly dazed.

“We all do, but I’m responsible.”

“And, you are . . .?”

“Pono Molefe. I am in your class, grade five.”

The Molefe’s were multiplying.

“The Principal . . .” she began, with an impatient shake of her tightly-braided hair.

“Yes, yes, the Principal.”

I followed her out of the classroom and turned towards Mokoka’s office.

He was with his two assistants, and the belated introductions were made with the briefest of ceremonies. One was Pitso Mogae. The other was Tankie Motaung.

Motaung looked hunted. He was about thirty-five – my sinful age – but his eyes were narrowed with old, atrophied grievances. His dark clothes were stiff and seemed too heavy even for the season.

Mogae was the direct opposite, almost as if on purpose. A large, multicoloured tie was the first thing that caught the eye. This was complemented with a faded pink shirt and a green suit. His mouth was always working too – cracking stale jokes and overflowing with good wishes and advice – while the silent Motaung’s face hung in the background like a misplaced planet.

Tankie Motaung was the grade one and two master, while Pitso Mogae held sway over the grade threes and fours. My dominion was grade five, but we were supposed to be able to teach those subjects we were good at any level (Mokoka himself took care of geography, history and religion across all grades). As the one at the end of the production line, I was supposed to iron out all the remaining kinks before sending the scrubbed and polished children to the schools in the nearest town.

“Let’s introduce you to the children,” Mokoka said as soon as the formalities were complete.

We went out to where sixty or so children – some of them wearing thin-looking clothes and shoes that were falling apart – were gathered in close, regular lines. They stood ranged before us – the shortest in front, the tallest at the back – their faces drifting from the unmistakably Khoisan to the decidedly Tswana without any marked break or transition, just as the arid Kgalagadi imperceptibly merges with the pastures of Lehurutse. Nothing was uniform about them, and, as in many rural schools, I expected to find a seven-year-old happily sharing a desk with a fourteen-year-old. This was against all progressive notions of education, yet it happens every day away from the beady eyes of the officials. The rural folk have a charming way of breaking the rules with such a disarming lack of consciousness of any wrongdoing that it is often very difficult to challenge them. So, the awkward, untidy adolescent sits next to a scrubbed, gap-toothed child wrapped in a patched shawl.

“It is sad that most of the giraffes at the back will never achieve much once they lose interest in book-learning,” Mokoka told me in low voice while Motaung berated the children for some vague misdeed. “They don’t appear on the official class lists, but we try to give them something while they are still here. Age is their problem, and a fast-changing world that seems to be leaving them behind. The old inspectors turned a blind eye, and some even encouraged them to stay as long as possible in the school system, but one never knows with these new ideas people.” He shrugged. “I always wonder how they turn out after they go to the big cities. Especially the poor girls. One always hears such terrible stories . . .” He shuddered. “But we can’t keep them here. There is nothing for them here anymore.”

This was when I began to warm to T. B. Mokoka. His concern was so genuine that I wanted to pat him on his back and assure him that none of it was his fault. I wished that he was at another school far away, preferably in a different province, in a saner, purer age.

The children sang and we sang with them. We chanted the Lord’s Prayer, whose noble sentiments have long lost their power through years of mindless repetition, before I was introduced to the children by a beaming Mogae.

* * *

During the lunch break I took a tour of the school. I found Mokoka eating something out of a small brown-paper bag in his office. He grimaced at me before returning to his lunch. Mogae, in turn, was in his classroom, chomping energetically. He also wrinkled the corners of his eyes in a simulated smile. Motaung was the only one not eating. Instead, he was marking books. As I had nothing to eat, I decided to join him. He looked up expressionlessly as I wandered in and sat down at the desk nearest to the door.

“It’s cold in here don’t you think?” I said, trying to make small talk. “Why don’t you sit outside in the sun?”

“The lunch break is too short for taking desks in and out of the classrooms,” he replied, and then, before I could object, he asked, “Have you been doing this for long?”

“Doing what?”

“Being a substitute teacher.”

“On and off . . . Maybe two, three years.”

“What type of schools? Urban or rural?”

For no reason at all, at that moment, Tankie Motaung struck me as having that indefinable quality of a sneak. To turn him away from asking about my life I replied to his last question with one of my own. “Where is Bullsdrift?” I asked.

“It’s our nearest town. You wouldn’t have seen it when you arrived. It’s on the other side of the turn-off.”

“I see,” I said and looked out through the window. “This lady teacher, the one who disappeared, how long had she been teaching here?” I continued, quickly moving in another direction to keep him off balance even as I studied his reflection in the windowpane.

“As long as the school has been here,” he said. I sensed a hesitation, a tightening of screws inside his head before answering, but he recovered himself quickly.

“And how long is that?”

“Four, five years.”

“And before all this,” I waved an arm. “Where did the Marakong children attend school?”

“At Majaneng,” he said. “The village that Mogae and I stay in.”

Motaung rose, seeming suddenly much older. “The lunch break is almost over. I have to prepare for the next lesson,” he said woodenly and with that I was dismissed.

After that the first day passed like any first day in a new environment: trying to memorise names and faces, the location of this and that, finding out who was responsible for what. On the whole it was pleasantly unthreatening in its banality.