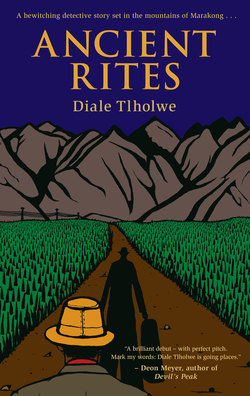

Читать книгу Ancient Rites - Diale Tlholwe - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 1

Chapter 1

A cold day, a cold journey and a cold voice in the vast emptiness between the mind and the place and the moment.

“The main thing is to separate the people you are going to be dealing with. Break the cliques.” He coughed and looked at me out of the corner of his left eye, his right eye remaining steady on the terrible untarred road we were on. He had been on this same subject since we had left Mafikeng two hours earlier. Not an invigorating, cobweb-clearing conversation for a cold Monday morning, especially when held in English – the language that Regional Education Director J. B. M. Tiro insisted on speaking.

R. E. D. Tiro wanted me to be prepared for the situation I was about to be faced with. He did not want me, he said, to arrive with preconceived ideas or to make any hasty judgements. He, on the other hand, was ready to make those judgements for me in a tiresomely oblique manner.

Strange the way some people get old before their time. Take the R. E. D. here. He was not yet fifty, but he talked and behaved like a falling tree that had long passed its point of equilibrium.

“Patience,” J. B. M. counselled. “Tact,” he urged.

“Yes, sir . . . Indeed, sir,” I replied at appropriate intervals as I idly wondered how many people knew what his initials stood for. Julius Brutus Maccabee. Ridiculous! The names some African parents burden their little angels with.

“Separate and watch them. There are those who will help you and there are those who will hinder you.” Another cough and sidelong glance. “They will be watching you too. That’s what they do in these places,” he cautioned. “Personally, I think you’re wasting everybody’s time, including your own. I am only doing this for the people who sent you here. People I respect. But I knew that woman was trouble the moment I . . .” He caught himself and stamped angrily on the brakes.

We had come to a long steep dip in the road that shook the car and Tiro stopped talking to concentrate on his driving. I took the opportunity to ponder the strange circumstances that had brought me to this remote place at the edge of South Africa.

* * *

Woman Educator Vanishes! the headline had screamed.

I read tabloids as my business is tabloidish anyway, but no matter how used you become to the lurid headlines it is always unsettling to have someone you know, or once knew, be the subject of them, however estranged you may have become. You wish that they had conducted their lives more responsibly. You are almost angry with them that they have not.

Mamorena Marumo had had many faces. I had known one, maybe two, or none at all. It is very difficult to love someone and never be sure if the feeling is mutual; to always be a stranger to the workings of their mind. And now, from out of the blue, there she was, demanding my attention again.

The newspaper reports had been vague, overblown and confusing. The media had gone howling into the dark corners of her life, but her parents, Mr and Mrs Marumo of KwaThema, Springs, had been killed in a car accident, and, seemingly, there was no one else to do the wailing in front of the cameras.

The police had made cautious public pleas for information and given guarded warnings to women in the area and the country in general, but, months later, the questions still remained. Questions and more questions. How does a city-bred teacher disappear without a trace in a rural village with a small, semiliterate population? And why had she taken up a teaching post there anyway? Did she have something to hide? And where was her car?

As the weeks had passed, anonymous female bodies had cropped up here and there in the district, but they had always turned out to be someone else. The general opinion was that the bodies were those of prostitutes who serviced the truck drivers who used the road to Botswana. They fuelled a delicious but short-lived panic about a serial killer, but then they had simply stopped appearing just as suddenly as they had first started being discovered.

Finally, the police chiefs and newspaper editors had retreated, turning to more tangible crimes and manageable controversies.

And it was then that the telephone call had come.

A telephone call to my home. A surprising start, as these days I conduct my business via a number linked to the office I share with two other disenchanted souls in Johannesburg. A call on my land line meant that someone had gone to the trouble of paging through old phone directories to find the number. But Mamorena Marumo was still missing and someone badly wanted me to find her. Someone who would not, or could not, let it go.

As a part-time hunter for absconding fathers, debt defaulters and summons dodgers, some hopeful souls obviously thought I might be able to do something. Anything. Especially since I had once known the supposed victim at the heart of the suspected crime. So I got the phone call and a large, cash-filled fast-mail envelope from nowhere in particular (it had been posted at the main Johannesburg post office). The voice on the phone had given me the name of a contact in Mafikeng, the provincial seat of the North West Province. It was the name of a high-ranking official in the province’s Department of Education. This contact was not to be involved except as a go-between, the voice on the phone had stressed. This was transparent nonsense of course. Sooner or later everybody gets involved, including not-so-innocent bystanders.

My partners, whose business flies under the radar as Ditoro and Thekiso: Security Consultants and Private Investigators, had nodded their bald heads gloomily as I had given them the bare bones of my new assignment earlier that morning.

I had been at high school with Thekiso before he left the country in the aftermath of the winter of 1976. He had been two years ahead of me, and in high school that meant we were a universe and a mile apart. He had not even remembered Mamorena when I sketched my new assignment for them, but had mumbled something about old flames being the warmest, whatever that meant.

I had promised to keep in touch and as usual they blessed me with the grim smiles they always produce at the beginning of every freelance job.

Four hours later I had arrived in Mafikeng in one of the Johannesburg-Mafikeng minibus taxis to be met by Tiro. It had been four hours of uproarious slander, scandal, sport, religion and, inevitably, politics as the ten other passengers battled it out between them, the driver acting as a stern referee. Tiro was no match for that revved-up, scrapping crowd in that busy green taxi, I thought, as I looked across at him, but nonetheless I was grateful that he had decided to hold his tongue for the time being.