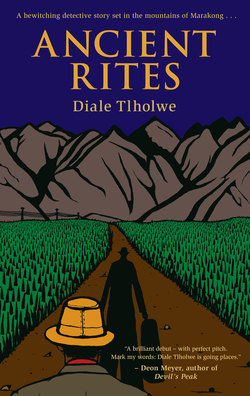

Читать книгу Ancient Rites - Diale Tlholwe - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 2

Chapter 2

“We are here,” the R. E. D. said.

We were there indeed. I took my first look at the place that was not shown on any of the maps I had consulted in my hurried preliminary research. A sad cluster of prefabricated sheds with badly-fitted windows made up the school.

“We are here,” R. E. D. Tiro said again. His voice had gone deep underground. He looked angry.

Two young men came out of different doors and stopped, looking at each other warily, as if uncertain which one of them would be the first to approach us.

“What are you standing there for?” R. E. D. Tiro asked fiercely, climbing out of the car. “I am the regional director! Come and meet your new colleague!”

He was very angry. I don’t know why. Perhaps he was not used to acting in an underhand manner and was embarrassed. He was, after all, putting his whole career on the line by subverting the rules of his own department. I suppose he was entitled to a little anger. But just a little, I thought, as I also climbed out of the car.

“Where is the acting Principal?” he shouted. Someone else might have left out the “acting” bit, but not J. B. M. Tiro

A short, stout, balding man emerged from the door of the only stand-alone structure and approached us with short, brisk steps, frowning disapprovingly until he recognised the R. E. D. He could have been the R. E. D.’s twin brother except that his spectacles were cloudy and his suit a wrinkled relic of a bygone age.

The R. E. D. glowered at him menacingly, and turned towards the three classrooms from which a most horrid howling could be heard.

The Principal bowed his head as if trying to identify individual voices within the uproar. “It is just the change of lessons,” he said as if trying to soothe the R. E. D. “You know . . . teachers going from one class to the next . . .”

The two teachers looked both defiant and abashed. Not an easy thing to achieve, so I gave them a bright smile. But the R. E. D. was now, suddenly, in a hurry, pushing all the little annoyances aside with a sweep of his short arm, and the two delinquents, sensing a storm building up from a different direction, scuttled off. The introductions were postponed.

“This is the temporary teacher I told you about. His name is Thabang Maje. Remember, he is only TEM-PO-RA-RY! Probably for less than three months until we can get you a PER-MA-NENT replacement. So there are no official forms to fill out. Everything has been done at head office.”

As he said this, I once again wondered about R. E. D. Tiro. What did the people who had brought us together have on him that was so damaging that he was prepared to break the rules with such suicidal abandon?

He was getting hot and angry again, his brow shiny with beads of sweat under the heatless winter sun. He looked at me scornfully, accusing me with his small eyes for the fabrications he was forced to utter.

The Principal coughed and glanced doubtfully at me. “Of course, sir. I hope he is qualified to . . .”

“Very qualified to teach anything you want him to,” Tiro said crushingly. “He is one of the all-rounders. He is sent to where there is a need. To fill the gaps as they arise. So make the most of him while you still have him here. He . . .” He stopped and barked out a short laugh. “Just listen to us,” he began again in a more conciliatory tone. “Just listen to us. We have not even exchanged names properly yet!” It was his show, but he was spreading the blame.

J. B. M. Tiro drew himself up and straightened his tie. We did the same. Three African men standing in the cold in a barren school yard on the edge of the new South Africa, trying to look dignified. Two short, stout, middle-aged men and a tall, slim, younger one, who could barely understand one another’s worlds. Three Batswana men alienated from one another by education, status, background, age, history and a language that was not their own.

The R. E. D. began to speak in his high diplomat voice. The voice I had found so soporific during the journey out to the school. He was listing the Principal’s virtues, interests and concerns in a bristling staccato: “Long career . . . dedicated service . . . the rural African woman and child . . . hard work . . . forgotten people . . . dying cultural values . . . UNESCO . . . no good land . . . Zimbabwe . . . restitution . . . AIDS . . . World Cup . . . hope and stability. Meet Mr T. B. Mokoka.”

The transition from smooth oration to exasperated introduction was so abrupt that neither I nor Mokoka moved or said anything for a few seconds. Personally, I had expected more – I had heard much more of the same on the drive out here – but J. B. M. Tiro had obviously reached and passed his daily quota of homilies.

The R. E. D. fixed his eyes on T. B. Mokoka’s anxious face, and I stumbled forward to shake his hand. He was, after all, the PRIN-CI-PAL of Marakong-a-Badimo Primary School, Molomo District, North-West Province, Republic of South Africa. Another grand old-timer who faced the world with only his initials as his spear and shield, I thought, as he shook my hand limply.

* * *

An hour later I found myself in the Principal’s office. I had expected a messy, gloomy cave, but it was a model of organisation and order. Even my two battered suitcases had been neatly placed beside one of the steel cabinets stationed against the right-hand wall. The wall opposite them was used as a bulletin board, and for maps, scientific data, mathematical formulae and stern Biblical exhortations. Two tables had been pushed against the lower half of the map wall and these had a neat row of children’s exercise books on top of them.

I was seated in a plastic chair facing the Principal’s polished desk and its neat piles of papers. Behind the desk a large window overlooked a scraggly vegetable patch. There was a tired, muddy stream a few hundred metres beyond that, and still further away I could see what could only be the outskirts of the village of Marakong-a-Badimo.

Sometime after the RED’s departure we had begun speaking in a hybrid of Setswana and English. This had seemed to lift Mokoka’s spirits somewhat. He had asked me about all the Maje’s he had ever known or heard of, looking for links and connections. Some I had heard of, but most were just names written in the wind, unknown and probably forever unknowable to me. Yet it was strangely comforting to know that they were out there, these Maje’s, whoever they might be, entangled in their own complexities and bafflements.

Now, T. B. Mokoka turned to the matter in hand. “You shall take over Miss Marumo’s class,” he began.

“Yes, sir.”

“Those are the grade fives.”

“I am ready, sir.”

T. B. Mokoka went on to tell me about my duties and his relief at my arrival. He told me everything twice over, wringing his hands distractedly as he alluded to problems of discipline and parental interference. “They are sometimes difficult,” he confided, “but they are very good children under the circumstances.”

Poor T. B., he didn’t know that before my premature retirement I had taught in a township high school for several years and had lived to tell my war stories to disbelieving novices. I didn’t see how these children’s circumstances could be that different to those of thousands of other children throughout the country.

Retirement. I turned the word over in my mind as Mokoka worried out loud over whether his problems were caused by too rigid a disciplinary regime or too little parental involvement.

At the time of my retirement I was only thirty, but I was burnt out. The educational field had become too complex. Old certainties had been overturned and washed away. New truths had been proclaimed. But when we had prophesied a new type of education, like countless others in all revolutions the world has ever seen, we had failed to foresee our own demise, our inevitable irrelevance in the new order.

Counselling had been recommended by the progressive management in the newly reorganised Department of Education, after what they called my “stressful experiences” at a rural school.

I had peaked too early, tried to do too much, Doctors Padayachee and Littlewater had pronounced in their separate turns. One had prodded my bones while the other had puzzled over my psyche. It was depressing for all three of us. Intensive medication and therapy was prescribed for me and high fees for them. I had vetoed both. They had sneered politely and consigned my depression to the back of their files while assuring me of their respect of my right to choose

After that it was only a short step to handing in my resignation.

However, all Mokoka was supposed to know was that I was a substitute teacher. Even my CV was to remain closed to him. As far as he was concerned I was just one of the rootless nomads of the teaching world, either one of the tramps, who shirk long-term commitment, or one of the pirates, who arrive, astound and then abdicate, thus earning the just wrath and unworthy envy of the more responsible members of the profession who have to remain behind and try to put Humpty Dumpty back together again.

So I smiled at him and asked him about the thing that really concerned me at this time.

“Sir, where am I going to rest my bones tonight?” I nodded at the sinking sun.

The school had long been dismissed and a brooding silence had fallen over the empty yard and classrooms.

“Ah, the matter of your accommodation. I think you will use the teacher’s cottage. Miss Marumo used it and Mr Tiro was insistent that you also use it. Something to do with saving money. Yours . . . or maybe the department’s . . . I am not too clear. It has been cleaned of course.” He added the last hurriedly. “But if you want alternative lodgings I can –”

“No, don’t bother,” I said, interrupting him. “The cottage will be fine.”

“Nothing of hers is still there. The police took it all. For their investigation. I have not heard from them since. But if you find anything. Anything. Please bring it to me. The police . . . I am sure you understand.”

“Do the other teachers live in the village?” I asked.

“No! No! No!” he cried, flapping his hand as if swatting at an obscenity uttered by a child. “They live in another village eight or nine miles from here. I pick them up in the morning and drop them off in the afternoon.” He coughed, looked away and flapped his hand again. “I myself live in Bullsdrift,” he continued with restrained pride.

A vague recollection of a dot on the map came hazily back to me and I tried to look impressed. At least the world knew that the town existed. Mokoka, like the rest of us, was not immune to some vanity. He had graduated from the dusty villages to a town, probably to the formerly whites-only part of it too. It was his due and he had earned it. Of what good was a long career, dedicated service, liberation and so on if Mokoka could not enjoy some of the rewards? If that is what he really equated freedom with.

“So I am alone in the cottage?” I asked.

“If you want alternative acco–” he tried once more, but I got in before he could finish.

“In fact, I don’t mind at all. I will enjoy the peace and quiet.”

“Peace and quiet,” he whispered to himself. “Yes . . . peace in our time.” He turned to me and shared his great revelation. “We always forget that.”