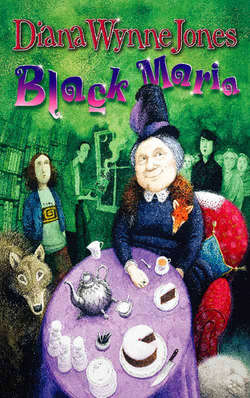

Читать книгу Black Maria - Diana Wynne Jones - Страница 10

CHAPTER THREE

ОглавлениеNow I feel as guilty as Mum. It got dark and Chris still hadn’t come back. Aunt Maria was really worried about him. “Suppose he’s gone down on the beach and slipped on a rock!” she kept saying. “If he’s broken his leg or twisted his ankle, nobody will know. I think you ought to ring the police, dear, and not bother about getting supper.”

Who wants the police, I thought, with Elaine after him? And Mum said, in the special high, cheerful voice she always uses to Aunt Maria, “Oh, he’ll be all right, Auntie. Boys will be boys.”

Aunt Maria refused to be comforted. She went on, low and direful, “And the pier is dangerous in the dark. Suppose the current took him. Thank goodness little Naomi is safe!”

“That makes me want to say I’m going out for a swim,” I said to Mum.

“You dare!” said Mum. “Chris is bad enough without you starting too.”

“Then shut her up,” I said.

“What’s that, dear?” said Aunt Maria. “Who’s shut up?”

It went on like that until the back door crashed open and Elaine marched Chris in, swinging her torch. She had hold of Chris by his shoulder, just as if she had arrested him. “Here he is,” she said to Mum. “I’ve given him a talking-to.”

“Really? How very helpful you are!” Mum said and took a quick anxious look at Chris’s face. He looked almost as if he was trying not to laugh, and I could see Mum was relieved.

By then Aunt Maria cottoned on. “Oh, Elaine!” she shouted. “I’ve been ill with worry! Have you brought him? Where did you find him? Is he all right?”

“In the street,” said Elaine. “He was on his way back here. He’s fine. Aren’t you, my lad?”

“Yes, apart from a squeezed shoulder,” Chris retorted.

Elaine let go of Chris and pretended to hit him with her torch. “Don’t let him do that again,” she said to Mum. “You know how she worries.”

“Stay with me, Elaine,” Aunt Maria bawled. “I’ve had such a shock!”

“Sorry!” Elaine bawled back. “I have to get Larry his supper.” And she went.

It was ages before I could ask Chris what Elaine had said to him. Aunt Maria made him sit down next to her and told him over and over again how worried she had been. She kept asking him where he had been and not giving him time to answer. Chris took it all in a humorous sort of way, so different from the way he had been before, that I thought Elaine must have hit him on the head with her torch or something.

“No, she just grabbed me,” Chris said. “And I said, ‘Do you arrest me in the name of the law?’ And she said, ‘You can be as rude as you like to me, my lad. I don’t mind. But I’m not having your aunt worried.’”

“What’s that?” said Aunt Maria. “Who’s worried?”

“Me,” said Chris. “Elaine worried me like a rabbit.”

“I expect Larry’s been out shooting,” said Aunt Maria. “He often brings home a rabbit. I wonder if he’s got one for us? I’m fond of rabbit stew.”

Chris looked at the ceiling and gave up. He’s playing his guitar at the moment and Aunt Maria is pretending not to hear that either. It looks as if All Is Forgiven. And that’s what makes me feel guilty. Mum and I have put Aunt Maria to bed and she’s sitting up on her pillows, all clean and rosy in her lacy white nightgown, with her hair in frizzy pigtails, listening to A Book at Bedtime on Mum’s radio. She looks like a teddy bear. Quite lovable. Mum asked her to say when she wants the electricity off, and she gave the sweetest smile and said, “Oh, when you’re ready. Let Naomi finish that story she’s writing so busily first.”

And I feel horrible. I’ve read through my notebook and it’s full of just beastly things about Aunt Maria and she thinks I’m writing a story. It’s worse than Chris, because I’m being secret in my nastiness. I wish I was charitable, like Mum. I admire Mum. She’s so pretty, as well as so cheerful. She has a neat little nose and a pretty forehead that comes out in a little bulge. Her eyes always look bright, even when she’s tired. Chris takes after Mum. They both have those eyes, with long curly eyelashes. I wish I did. What eyelashes I have are butterscotch-colour, like my hair, and they do nothing for plain brown eyes. My forehead is straight. I am not sweet at all and I wish Aunt Maria would not keep calling me her “sweet little Naomi”. I feel a real worm.

I felt so bad after that, that I just had to talk to Mum before we blew out the candle. We both sat up in bed. Mum smoked a cigarette and I cried, and we both expected Aunt Maria to wake up and shout that the house was on fire. But she didn’t. We could hear her snoring, while downstairs Chris defiantly twanged away at his guitar.

“My poor Mig!” said Mum. “I know just how you feel!”

“No, you don’t!” I snuffled. “You’re charitable. I’m worse than Chris even!”

“Charitable be damned!” said Mum. “I want to slay Auntie half the time, and I could strangle Elaine all the time! At first, I was as muddled as you are, because Auntie is very old and she can be very sweet, and I only got by because I do rather like nursing people. Then Chris did me a favour, behaving like that. He was admitting something I was pretending wasn’t there. People do have savage feelings, Mig.”

“But it’s not right to have savage feelings,” I gulped.

“No, but everyone does,” said Mum, lighting a second cigarette off the end of the first. “Auntie does. That’s what’s upsetting us all. She’s utterly selfish and a complete expert in making other people do what she wants. She uses people’s guilt about their savage feelings. Does that make you feel better?”

“Not really,” I said. “She has to make people do things for her, because she can’t do things for herself, can she?”

“As to that,” Mum said, puffing away, “I’m not convinced, Mig. I’ve been looking at her carefully and I don’t think there’s much wrong with her. I think she could do a lot more for herself if she wanted to. I think she’s just convinced herself she can’t. Tomorrow I’m going to have a go at making her do some things for herself.”

That made me feel better. I think it made Mum feel better too, but she hasn’t made much headway getting Aunt Maria to do things. She’s been trying half the morning. Aunt Maria will say, “I left my spectacles on the sideboard, but it doesn’t matter, dear.”

“Off you go and get them,” Mum says, in a cheerful loud voice.

There is a pause, then Aunt Maria utters in a reproachful gentle groan, “I’m getting old, dear.”

“You can try at least,” Mum says encouragingly.

“Suppose I fall,” suggests Aunt Maria.

“Yes, do,” says Chris. “Fall on your face and give us all a good laugh.” Mum glares at him and I go and find the spectacles. That’s the way it was until the grey cat suddenly put in an appearance, mewing through the window at us with its ugly flat face almost pressed against the glass. Aunt Maria jumped up with no trouble and practically ran to the window, slashing the air with both sticks and shouting at the cat to go away. It fled.

“What did you do that for?” Chris said.

“I’m not having him in my garden,” Aunt Maria said. “He eats birds.”

“Who does he belong to?” Mum asked. She likes cats as much as I do.

“How should I know?” said Aunt Maria. She was so annoyed with the cat that she took herself back to the sofa without remembering to use her sticks once. Mum raised her eyebrows and looked at me. See? Then we unwisely left Chris indoors and went out to look for the cat in the garden. We didn’t find it, but when we got back Chris was simmering. Aunt Maria was giving him a gentle talking-to.

“It doesn’t matter about me, dear, but my friends were so distressed. Promise me you’ll never speak like that again.”

Chris no doubt deserved it, but Mum said hastily, “Chris and Mig, I’m going to make you a packed lunch and you’re going to go out for some fresh air. You’re to stay out all afternoon.”

“All afternoon!” cried Aunt Maria. “But I have my Circle of Healing here this afternoon. It will do the children such a lot of good to come to the meeting.”

“Fresh air will do them more good,” said Mum. “Chris looks pale.” Which was true. Chris looked as if he hadn’t slept much. He was white and getting one or two spots again. Mum took no notice of Aunt Maria’s protests – it was windy, it was going to rain, we would get wet – and bullied us out of the house with warm clothes and a carrier bag of food. “Do me a favour and try and enjoy yourselves for a change,” she said.

“But what about you?” I said.

“I’ll be fine. I shall do some gardening while she has her meeting,” Mum said.

We went out into the street. “She’s martyring herself,” I said. “I wish she wouldn’t.”

Chris said, “She needs to work off her guilt about Dad. Let her be, Mig.” He smiled in his normal understanding way. He seemed to go back to his old self as soon as we were in the street. “Shall I tell you something I noticed about this street yesterday? See that house opposite?”

He pointed and I said, “Yes,” and looked. And the lace curtains in the front window of the house twitched as somebody hastily got back from them. Otherwise it was a little cream-coloured house as gloomy as the rest of the street, with a large 12 on its front door.

“Number Twelve,” said Chris as we walked on up the street. “The only house in this street with a number, Mig, apart from Twenty-two down the other end on the same side. That means odd numbers on Aunt Maria’s side, doesn’t it? And that makes Aunt Maria’s house Number Thirteen whichever way you count the houses.”

Chris is always thinking about numbers normally. This proved he was back to normal. I said it would be Number Thirteen, and we laughed as we walked down to the sea front. It was very windy and quite deserted there, but very respectable somehow. Chris shouted that even the concrete sheds were tasteful. They were. We went past the kiddies’ bathing pool and the tame little place with swings, and along the front. The tide was in. Waves came spouting up against the sea wall, grey and violent, sending water bashing across the path. Our feet got wet and the noise was so huge that we talked in shouts and licked salt off our mouths afterwards. There was only one other person out that we saw, the whole length of the bay, and he was right at the beginning – an elderly gent huddled in a tweed coat, who tried to raise his tweed hat politely to us; but he only put a hand to it, in case it got blown away.

“Morning!” we shouted. He shouted, “Afternoon!” Very correct. It was after midday. Only I always think afternoon begins when you’ve had lunch, and we hadn’t yet.

When we were near the pier, I shouted to Chris, “The ghost in your room – is it a he or a she?” It was a bad place to ask important things. The sea was crashing and sucking round the iron girders, and the buildings on the pier kept cutting the wind off, so that we were in a nest of quiet one moment, all warm with our ears ringing, and then out again into icy noise.

“A man!” yelled Chris. “And it’s not Dad,” he said, as we went into a nest of quiet. “I saw you thinking it might be and it’s not. It’s ever such a strange-looking fellow, like a cross between a court jester and a parrot.”

The wind howled and I didn’t hear straight. “A pirate? ”I shouted.

“Parrot! ”Chris screamed. And I think what he shouted after that was “Pretty Polly! Long John Silver! I am the ghost of Able Mabel! Parrot cage on table!”

Shouting in the wind makes you shout silly things anyway, and I think Chris was shouting in order not to be scared. Anyway I got in a real muddle and I thought he was trying to tell me the ghost’s name. “Neighbour?” I yelled. “John?”

“What do you mean, Neighbour John?” howled Chris.

“The ghost’s name. Is it Neighbour John?” I screeched.

By the time we got into a pocket of quiet again and sorted out what we both thought we were saying, we were in fits of laughter and Neighbour John seemed a good name for the ghost. So we call him that now. I keep thinking of Chris seeing a large red pirate parrot, and then I remember he said “court jester” too, so I correct the red parrot into one of those white ones with a yellow crest that are really cockatoos. I think their crests look like jester’s caps, and ghosts should be white. But I just can’t imagine a man looking like that.

Chris told me more about the ghost at intervals all through the day. I think he was glad to have someone to tell. But I know there were things he didn’t tell, and I keep wondering why, and what they were.

He said he woke up suddenly the first night, thinking he’d forgotten to blow out the candle. But then he realised it was light coming in from a street light somewhere. He could see a man outlined against the window, bent over with his back to Chris. The man seemed to be hunting for something in one of the bookcases.

“So I called out to him,” said Chris.

“Weren’t you scared?” I said. My heart seemed to be beating in my throat at just the idea. “Yes, but I thought he was a burglar then,” Chris said. “I sat up and thought about people getting killed for surprising burglars and decided I’d pretend I was sleeping with a gun under my pillow. So I said, ‘Put your hands up and turn round.’ And he whirled round and stared at me. He looked absolutely astonished – as if he hadn’t realised there was anyone else there – and we sort of stared at one another for a while. By that time I knew he wasn’t a burglar, somehow. He had the wrong look on his face. I mean, I know he was odd-looking, but it wasn’t a burglar-look. I even almost knew he had lost something that belonged to him and he was looking for it because it was in that room. So I said, ‘What have you lost?’ and he didn’t answer. There was a look on his face as if he was going to speak, but he didn’t.”

Chris said he still didn’t realise the man was a ghost, even then. At first he said he only realised next morning when he snapped at me there was a ghost in his room. Then he said, no, he must have known the moment the man turned round. The room was full of an odd feeling, he said. Then he corrected himself again. I think ghosts must be muddling things to meet. He said he began to be puzzled when he noticed the man was wearing a peculiar dark green robe, all torn and covered with mud.

By the time Chris had told me that far, we had got right along the sea front, past all the little boats pulled up on a concrete slope, almost to Cranbury Head. We looked up the great tall pinkish cliff. It looked almost like a house, because creepers grow up it. We could just see the gap in the creepers and a glimpse of the new fence. And we both went very matter-of-fact, somehow.

Chris said, “You can see some of the rocks at the bottom, even with the tide in.”

“Yes, but it was at night,” I said. “They didn’t see the car till morning.”

Then Chris wondered how they got the car cleared away. He thought they winched it up the cliffs. I said it was easier to put it on a raft and float it to the concrete slope. “Or drag it round the sands at low tide,” Chris agreed. “Poor old car.”

We turned and went back through the town then. I kept thinking of the car. I know it so well. It was our family car until six months ago, when Dad took a lady called Verena Bland to France in it and phoned to say he wasn’t coming back. I wondered if the car still had the messy place on the back seat where I knelt on an egg while I was fighting with Chris. Does sea water wash out egg? And I remembered again that I’d left the story I was writing in that hiding-hole under the dashboard. All washed out with the sea water. I hated to think of that car smelling of sea and rust. It used to have a smell of its own. Dad once got into the wrong car by accident and knew it was wrong by the smell. Chris didn’t get on with Dad. I did, a lot of the time, unless Dad was in a really foul mood.

“When did you know it was a ghost then?” I said.

“Right at the end, I suppose,” Chris said. “He didn’t speak, but he gave a great mischievous sort of smile. And while I was wondering what was so funny, I realised I could see books on the shelf through him and he was sort of fading out.”

That makes four different versions, I thought. “Weren’t you frightened?”

“Not so much as I expected,” Chris said. “I quite liked him.”

“And has he come every night?” I asked.

“Yes,” said Chris. “I keep asking him what he wants, and he always seems to be just going to tell me, but he never does.”

It was windy among the houses too, cream houses, pink houses, tall grey houses with boards saying Bed and Breakfast, creaking in the wind, and sand racing across the roads like running water.

The place had been deserted up to then, but after that we kept meeting Mrs Urs. We saw Benita Wallins first, puffily shaking a rug out of the front door of a Bed and Breakfast house. She shouted, “Hello, dears.” Then there was Corinne West, coming round a corner with a shopping basket, Selma Tidmarsh in the next street with a scarf over her head, and Ann Haversham walking a dog round the corner from that. It was “Hello, how are you? Is your aunt well?” each time.

“Aunt Maria will be able to plot our course exactly at this rate,” I said. “Or Elaine will. How many more of them?”

“Nine,” said Chris. “She talks about thirteen Mrs Urs. I read a book and counted while she was talking yesterday.”

“Only if you count Miss Phelps and Lavinia too,” I said. “What did Miss Phelps say to upset her? Did she tell you?”

“No. Unless it was ‘Stop that boring yakking,’” Chris said. “Let’s get on a bus and get out of this place.”

But the buses don’t start until next month. We went to the railway station and asked. A porter in big rubber boots told us it was out of season, but we could get a train to Aytham Junction, and it turned out that we hadn’t got enough money for that. So we walked out along the path that started by the station car park, through brown ploughed fields to the woods.

“I think it was the day after that I noticed mud on his robes,” Chris said, looking at the ploughed earth. He kept talking about the ghost like that, in snatches. “And the light seems to come with him. I experimented. I went to bed without a candle last night and I could hardly see to find the bed.”

“Do you wake up each time?” I said.

“The first two nights. Last night I stayed awake to see if I could catch him appearing.” Chris yawned. “I heard the clock strike three and then I must have dropped off. He was just there suddenly, and I heard four strike around the time he faded out.”

We had lunch in the woods. They were good, lots of little trees all bent the same way by the sea wind. Their trunks grow in twists from all the bending they get. It gives the wood a goblin sort of look, but as soon as you are among the goblin trees you can’t see any open land outside. We nearly got lost later because of that.

“But what’s the ghost looking for?” I said. I know that was during lunch because I could hear the twisted trees creaking while I said it, and I remember dead leaves under my knees, clean and cold as an animal’s nose.

“I’d love to know,” Chris said. “I’ve looked all along the books in that wall. I took them out and looked behind them, in case the ghost hadn’t the strength to move them, but it’s just wall behind them.”

“Perhaps it’s a book?” I suggested. “Are any of them A History of Hauntings, or maybe Dead Men of Cranbury, to give you a clue who he is?”

“No way!” said Chris. “The Works of Balzac, The Works of Scott, Ruskin’s Writings and Collected Works of Joseph Conrad.” He thought a bit and the trees creaked a bit, and then he said, “I think the ghost brings rather awful dreams, but I can’t remember what they are.”

“How can you like him then?” I cried out, shuddering.

“Because the dreams are not his fault,” Chris said. “You’d know if you saw him. You’d be sorry for him. You’re the soft-hearted one, not me.”

I do feel quite sorry for the ghost anyway, not being able to lie quiet because he’d lost something, and having to get up out of his grave every night to hunt for it. I wondered how long he’d been doing it. I asked Chris if he could tell from the ghost’s clothes how long ago he died, but Chris said he never saw them clearly enough.

The creaking of the trees was making me shudder by then. I couldn’t finish my lunch – Mum always gives you far too much anyway. Chris said he was blowed if he was going to cart a bag full of half-eaten pork pie about and I hate carrying carrier bags. So Chris put some of the cake in his pocket for later and we pushed the bag under the twisted roots of the nearest tree. Litter fiends, we are. The wood was wonderfully clear and airy, with a fresh mossy smell to it. It made it seem cleaner still that there were no leaves on the bent branches – barely even buds. We both felt ashamed of leaving the bag and made jokes about it. Chris said a passing badger would be grateful for the pork pie.

It was after that that we got lost. The wood went steeply up and steeply down. We never saw the fields, or even the sea, and we didn’t know where we were until I realised that the wind always came in from the sea. So in order to find Cranbury again we had to face into the wind. We might have been wandering all night if we hadn’t done that. I said it was a witch-wood trying to keep us for ever. Chris said, “Don’t be silly!” But I think he was quite scared too: it was all so empty and twisted.

Anyway, I think what we must have done was to go right up the valley behind Cranbury and then along the hill on the other side. When we finally came steeply down and saw Cranbury below us, we were right on the opposite hill from Cranbury Head, and Cranbury was looking like half-circles of doll’s houses arranged round a grey misty nothing that was the sea.

I thought it looked quite pretty from there. Chris said, “How on earth did we cross the railway? It comes right through the valley.”

I don’t know how we did, but we had. We could see the railway below us too. The last big house in Cranbury was half-hidden by the hill we were on, quite near the railway. We took it as a landmark and went down straight towards it. By this time it was just beginning to be evening, not dark yet, but sort of quietly dimming so that everything was pale and chilly. I kept telling myself this was why everything felt so strange. There was a steep field first of very wet grass. The wind had dropped. The big house was all among trees, but we thought there must be a road beyond it, so we climbed a sort of mound-thing at the bottom of the field to see where the road was. The mound was all grown over with whippy little bushes that were budding big pale buds and there were little trampled paths leading in and out all over. I remember thinking that it looked a good place to play in. Children obviously played here. Then we got to the top of the hill and we could see the children.

They were in the garden of the big house. It was a boring red-brick house that looked as if it might be a school. The garden, which we could look down into across a wall, was a boring school-type garden, too, just grass and round beds with evergreens in them. The children were all playing in it, very quietly and sedately. It was unnatural. I mean, how can forty kids make almost no noise at all? The ones who were playing never shouted once. Most of them were just walking about, in rows of four or five. If they were girls, they walked arm in arm. The boys just strolled in a line. And they all looked alike. They weren’t alike. All the girls had different little plaid dresses on, and all the boys had different coloured sweaters. Some had fair hair, some brown hair, and four or five of the kids were black. Their faces weren’t the same. But they were, if you see what I mean. They all moved the same way and had the same expressions on their different faces. We stared. We were both amazed.

“They’re clones,” said Chris. “They have to be.”

“But wouldn’t clones be like twins?” I said.

“They’re part of a secret experiment to make clones look different,” Chris said. “They’ve managed to make their bodies not look alike, but their minds are still the same. You can see they are.”

It was one of those jokes you almost mean. I wished Chris hadn’t said it. I didn’t think the children could hear him from where we were, but a man came up beside me from the bushes while Chris was talking, and I knew the man could hear. Luckily at that moment, a lady, dressed a bit like a nurse, came out into the garden.

“Come along, children,” she called. “It’s getting cold and dark. Inside, all of you.”

The lady was one of the Mrs Urs. As the children all obediently walked towards her, I remembered she was Phyllis Forbes. I was going to tell Chris, but I looked at the man first because it was embarrassing with him standing there. He seemed to have gone. So I looked at Chris to tell him and Chris’s face was a white staring blur, gazing at me.

“You look as if you’ve seen a ghost!” I said.

“I have,” he said. “The ghost from my room. He was standing right beside you a second ago.”

I ran then. I couldn’t seem to stop myself. I went tearing my way through the bushes all across and down the little hill and then out into a field of some kind and then into another field after that. I remember a wire fence twanging and a hedge which scraped me all over, and a huge black and white beast suddenly looming at me out of the twilight. It was a cow, I think. I did a mad sideways swerve round it and ran on. I wanted to scream, but I was so frightened that all I could make was a little whimpering sound.

After a while I could hear Chris pelting after me, calling out, “Cool it, Mig! Wait! He’s not frightening at all really!” I wanted to shout back, “Then why did you look so scared?” but I could still only make that stupid mewing noise. “Hm-hm-hm!” I said to Chris and rushed on. I don’t know where I went at all, with Chris rushing after me telling me to stop. It was getting darker all the time. But I think some of where I ran must have been allotments along the back of Cranbury, because it was all cold and cloggy and I kept treading on big clammy plants that went crunch and gave out a fierce smell of cabbage. My feet got heavier and heavier like they do in nightmares. I could see town lights twinkling to one side and orange street light shining steadily ahead, and I raced for the orange light with my huge heavy feet, and my chest hurt and I kept going “hm-hm-hm!” until Chris caught me up and I suddenly ran out of breath.

“Honestly!” he said. He was disgusted.

We were beside an iron fence just outside the station car park, with dew hanging off it and glittering on all the cars in the orange light. A train was just coming rattling into the station. I had a stitch and I could hardly breathe. I lifted first one foot then the other into the light. They were both giant-sized with earth and smelt of cabbage. We looked at them and we laughed. Chris leant on the fence and squealed with laughter. I hiccuped and panted and my eyes watered.

“It wasn’t really the ghost,” I said when I could speak, “was it?”

“I just said it to frighten you,” said Chris. “The result was spectacular. Get some of that mud off. Aunt Maria will be telling everyone we’re drowned and Elaine will be giving Mum hell for letting Auntie get so worried.”

Now I’m writing it down, I can see Chris was lying to make me feel better. I didn’t realise then and I did feel better. I stood on one leg and took my shoes off in turn and scraped them on the iron fence. Chris scraped his a bit, but he wasn’t anything like as muddy. He had looked where he was going.

While we were doing it, the train had stopped and all the people from it began to come out of the station. They came one after another along past the fence under the light. They didn’t look at us. They were all staring straight ahead and walking in the same brisk way, looking kind of dull and tired. “Rush-hour crowd,” Chris said. “Funny to have it out here too. I wonder where they all commute to.”

“They look like zombies,” I said. Most of them were men and they mostly wore city suits. About half the line marched out through the gate at the end of the car park. We could hear their feet marching twunka twunka twunka down the road into Cranbury. The other half, in the same unseeing way, walked to cars in the car park. The space was suddenly full of headlights coming on and starters whining. “Zombies tired after work,” I said.

“All the husbands of the Mrs Urs,” said Chris. “The Mrs Urs take their souls away and then send them out as zombies to earn money.”

“But the Mr Urs don’t realise,” I said. “They’ve all been zombies for years without anyone knowing.” The cars were all zooming out of the car park by then, crunchle crunchle as they came past us on the gravel, flaring headlights over us. The zombies in each car looked straight ahead and didn’t notice us staring over the fence. Car after car. It was giving me a mesmerised feeling, until one crunched by that was blue, with one headlight dimmer than the other and dents in well-known places. “Hey!” I cried out. I hung on to the fence so that my hands hurt. “Chris, that was—!”

“No, it wasn’t,” Chris said. He was hanging on the fence too. “It had the wrong number. I thought it was our car too for a moment, but it wasn’t, Mig. Truly.”

You can rely on Chris where numbers are concerned. He’s always right. “It was awfully like ours,” I said.

“Creepily like,” Chris agreed. “I really did wonder if they’d dried it out and mended the door and sold it to someone – for a second, till I looked at the number plate.”

By the time all the cars had driven away, the porter in sea boots was padding about in front of the station, closing it for the night by the look of it. We climbed over the fence and trotted out through the car park gates.

“We’d better not tell Mum,” I said.

“No,” said Chris. “We can tell her we’ve seen clones and zombies, but not about the car.”

In the end, we didn’t tell Mum anything much. We were in trouble – both of us for being so late and me about the state my clothes were in. Aunt Maria was really put out about my clothes. “So thoughtless, dear. I can’t take you to the Meeting looking like that.”

“I thought your meeting was this afternoon,” Chris said.

Mum shushed him. She was in a frenzy. The Mrs Urs had been there all afternoon having their Circle of Healing and wolfing cake, and now Aunt Maria had announced that there was a Meeting at Cranbury Town Hall she had to go to at 7.30. That is the reason I have been able to write so much of this autobiography. I have been left behind in disgrace because I have got my only skirt torn and covered in mud. I like being in disgrace. There is still some cake left. Aunt Maria used her low sorrowing voice on me and then told Chris he had to go instead. Mum took one look at Chris’s face and martyred herself again by saying she would go with Aunt Maria.

I can’t think why Aunt Maria needs Mum. When zero hour approached, Elaine and her husband came round with the famous wheelchair. Mr Elaine – who is called Larry – is smaller than Elaine and I think he was one of the line of zombies who got off the train. Anyway he has a pale, drained, zombie-ish look and does everything Elaine says. The two of them unfolded the vast, shiny wheelchair in the kitchen and heaved Aunt Maria into it. Chris had to go away and laugh. He says Aunt Maria looked like the female pope.

At zero hour minus one, Aunt Maria had made Mum array her in a large purple coat, with most of a dead fox round her neck. The fox’s head is very real, with red glass eyes, and it spoilt my supper, because Aunt Maria had supper in it in case they were late. And her hat, which is tall and thin with purple feathers. The wheelchair looked like a throne when she was in it. She kept snapping commands.

“Betty, my umbrella, don’t forget my gloves. Larry, mind the rug in the hall. Be careful down the steps.”

And Elaine always answered for Larry. “Don’t worry. Larry’s got it in hand. Larry can do the steps blindfold.” Larry never said a thing. He looked at me and Chris as if he didn’t like us. Then he and Mum and Elaine took Aunt Maria bumping down the front step and wheeled her off down the street like a small royal procession.

The Meeting was about Cranbury Orphanage. It turns out that the house where we saw Mrs Ur and the clones – and the ghost – is Cranbury Orphanage. How dull. It makes the whole day seem dull now, if they were only orphans, not experimental clones after all. Mum thought the Meeting was pretty dull too. When I asked her about it just now, she said, “I don’t know, cherub. I was asleep for most of it – but I think they were voting on whether or not to build an extension to the Orphanage. I remember a dreary old buffer called Nathaniel Phelps was dead against it. He talked for ages, until Aunt Maria suddenly banged her umbrella on the floor and said of course they were going to build the poor orphans a new playroom. That seemed to settle it.”

I think Aunt Maria is secretly Queen of Cranbury – not exactly “Uncrowned Queen”, more like “Hatted Queen”. I am glad I am not an orphan in that Orphanage.