Читать книгу Black Maria - Diana Wynne Jones - Страница 6

CHAPTER ONE

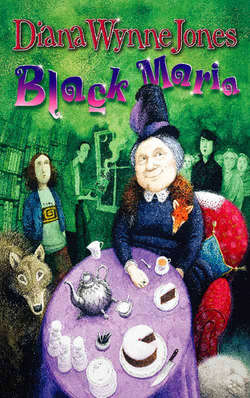

ОглавлениеWe have had Aunt Maria ever since Dad died. If that sounds as if we have the plague, that is what I mean. Chris says it is more like that card game, where the one who wins the Queen of Spades loses the game. Black Maria, it is called. Maybe he is right.

That is the first thing I wrote in the locked journal Dad gave me that awful Christmas, but I think it needs an explanation, so I will squeeze some in. Dad left early in December and took the car. He rang up suddenly from France, saying he had gone away with a lady called Verena Bland and wouldn’t be coming back.

“Verena Bland!” Mum said. “What an awful name!” But she said it in a way which meant that wasn’t the only awful thing. Chris doesn’t get on with Dad. He said, “Good riddance!” and then got very annoyed with me because all I seemed to be able to think of was that Dad had gone off with the story I was writing hidden in our car in the space on top of the radio. I mean I was upset about Dad, but that was the way it took me. At that time I thought the story was going to be a masterpiece and I wanted it back.

Of course Dad had to come back. That was rather typical. He had left a whole lot of stuff he needed. He came and fetched it at Christmas. I think Verena Bland had disappeared by then, because he came with a necklace for Mum and a new calculator for Chris. And he gave me this lovely fat notebook that locks with a little key. I was so pleased about it that I forgot to ask for my story from the car, and then I forgot it completely because Mum and Dad had a whole series of hard, snarling rows and Mum ended up saying she wanted a divorce. I still can’t get over it being Mum who did! Nor could Dad, I think. He got very angry and stormed out of the house and into our car and drove away without all the stuff he had come to fetch. But my story went with him.

He must have driven off to see Aunt Maria in Cranbury-on-Sea. He was always very dutiful about Aunt Maria, even though she is only his aunt by marriage. But he never got there, because the car skidded on some ice going over Cranbury Head and went over the cliff into the sea. The tide was up, so he could have been all right even so. But there was something wrong with the door on the driver’s side. It had been like that for six months and you had to crawl in through the other door. The police think the passenger door burst open and the sea came in and swept him away while he was stunned. The seatbelt was undone, but he may have forgotten to fasten it. He often did forget. Anyway, they still haven’t found him.

Inquest adjourned. That is the next thing I wrote. Mum doesn’t know if she’s a widow or a divorcee or a married lady. Chris says “Widow”. He feels bad about saying “Good riddance!” the way he did before, and he got very annoyed with me when I said Dad could have been picked up by a submarine that didn’t speak English or swum to France or something. “There goes Mig with her happy endings again,” Chris said. But I don’t care. I like happy endings. And I asked Chris why something should be truer just because it’s unhappy. He couldn’t answer.

Mum had gone all guilty and agonising. She sent Neil Holstrom packing, and I thought Neil was going to be her boyfriend. Actually, even when I wrote that I wasn’t sure Mum liked Neil Holstrom, but I wanted to be fair. Neil reminded me of an earwig. All Mum did was buy Neil’s nasty little car off him, which was hard on Neil, even though I was glad to see the back of him. But it was true about Mum going all guilty. Chris and I went rather strange too – sort of nervy and soggy at the same time – and couldn’t settle down to do anything. There are huge gaps in the notebook when I couldn’t be bothered to write things in it.

Mum’s worst guilt was about Aunt Maria. She said it was her fault Dad had gone driving off on icy roads to see Aunt Maria. Aunt Maria took to making Lavinia, the lady who looks after her, ring up twice a day to make sure we were all right. Mum said Aunt Maria had had quite as much of a shock as we had, and we were to be nice to her. So we were all far too nice to Aunt Maria. And suddenly we had gone too far to start being nasty. Aunt Maria kept ringing up. If we weren’t in, or if it was only Chris at home and he didn’t answer the phone, Aunt Maria telephoned all our friends, even Neil Holstrom, and anyone else she could get hold of, and told them that we’d disappeared now and she was ill with worry. She rang our doctor and our dentist and found out how to ring Mum’s boss when he was at home. It got so embarrassing that we had to make sure one of us was always in the house from four o’clock onwards to answer the phone.

It was usually me who answered. Mum worked late a lot around then, so that she could get off work and spend Easter with us. The next thing in my notebook is about Aunt Maria phoning.

Chris has a real instinct for when it’s going to be Aunt Maria. He says the phone rings in a special, gently persistent way, with a clang of steel under the gentleness. He gathers up his books the moment it starts and makes for the door, shouting, “You answer it, Mig. I’m working.”

Even if Chris isn’t there to warn me, I know it’s going to be Aunt Maria because the first person I hear is the Operator, sounding annoyed and harassed. Aunt Maria always grandly forgets that you can look up numbers and then dial them. She makes Lavinia go through the Operator every time. Lavinia never speaks. You just hear Aunt Maria’s voice distantly shouting, “Have you got through, Lavinia?” and then a clatter as Aunt Maria seizes the phone. “Is that you, Naomi dear?” she says urgently. “Where’s Chris?”

I never learn. I always hold the phone too near my ear. She knows London is a long way away from Cranbury, so she shouts. And you have to shout back or she yells that you are muttering. “This is Mig, Auntie,” I shout back. “I prefer to be called Mig.” I say that every time, but Aunt Maria never will call me anything but Naomi, because I was called Naomi Margaret after her daughter that died. Then I transfer the receiver to my other ear and rub the first one. I know that she’s shouting to know where Chris is again. “Chris is working!” I shriek. “Maths!”

She respects that. Chris has somehow managed to fix it in her mind that he is a mathematical genius and His Work Is Sacred. I wish I knew how he did. I would like to fix it in her mind that I am going to be a Great Writer and my time is precious, but she seems to think only boys have the right to have ambitions.

Aunt Maria’s voice takes on a boomingly reproachful note. “I’m very worried about Chris,” she says, as if that is my fault. “I don’t think he gets enough fresh air.”

That starts the tricky bit. I have to convince her that Chris gets plenty of fresh air without telling her how he gets it. If I say he goes to see his friends, then either she says Chris is neglecting his work or she rings his friends to check. I nearly died the time she rang Andy. I want Andy to think well of me. But if I leave it too vague, Aunt Maria becomes convinced that Chris is in Bad Company. She will ring Chris’s form master then. I nearly died when she did that too. Mr Norris asked me about Aunt Maria every time he passed me in the corridor. She obviously scarred his soul.

But I’ve learnt how to do it now. Chris will be surprised to know that he plays tennis every day with a friend who isn’t on the phone. Then I have to do the same for Mum. Mum plays tennis, too, with the phoneless friend’s mum – who is a widow, in case Aunt Maria gets worried about that. Then we get on to me. For some reason, I am not supposed to do anything, even get fresh air. Aunt Maria says, “And what a good little girl you are, Naomi, working away, keeping house for your mother!”

I agree with this, for the sake of peace, though it always makes me want to say, “Well, really, I’m just off to burn the church down on my way to the nudist colony.”

After that she goes on to her latest theories about what really happened to Dad, and then to how upset she is. All I can do there is shout a soothing “Ye-es!” every so often. That part makes me feel awful. But I have to keep listening, because that part always leads to us being the only family she’s got now, and then, “So when are you all coming to Cranbury to visit me?”

This is where I get truly artful. Aunt Maria gets enticing. She says, “Chris can have the sofa, and if Lavinia moves down to the little room, you and Betty can share Lavinia’s room.”

“How kind!” I say. “But I’m afraid Chris has this exam.” You wouldn’t believe how often Chris has exams. Chris doesn’t mind. He gives me suggestions. One thing Chris and I were really determined on was that we were not ever going to visit Aunt Maria in Cranbury-on-Sea. We both have dreadful memories of going there as small children.

Now of course we had other reasons. Would you want to go and stay in the place your father didn’t quite get to before he died? No. So I put Aunt Maria off. I did it beautifully. I kept it all politely vague for months, and we were looking forward to the Easter holidays, when Mum answered the phone one evening I was out and undid all my good work in seconds. I got back to find she had agreed for us to spend Easter with Aunt Maria.

Chris and I were furious. I said I thought it was very unfeeling of Aunt Maria to make us go. Chris said, “There’s no reason to have anything to do with her, Mum. She was only Dad’s aunt by marriage. She’s got no claim.”

But Mum’s guilt was working overtime. She said, “It would be horrible not to go if she wants us. She’s a poor lonely old lady. Dad meant a lot to her. It will make her terribly happy to have us there. We’re going. It would be really selfish not to.”

So here we all are at Aunt Maria’s house in Cranbury-on-Sea. We only got here this evening and I’m so depressed already that I decided to write it all down. Mum said that if I am going to write rude things about Aunt Maria, I’ll have to make sure she can’t read it. So I sighed heavily and decided to use my hardback notebook with the lock on it. I was going to use most of it for my league table of King Arthur’s knights and pop groups, because I didn’t want Chris to find those and jeer, but I’d rather have Chris on to me than Aunt Maria any day. This will be under lock and key when I’ve written it down.

Unfortunately, Mum drove us down in Neil’s car. It’s small and slow, with so little space for people that Chris’s guitar was digging into me all the way; and there are horrible crunching noises from the suspension when you drive with luggage in. Chris and I wanted to go by train. That way we wouldn’t have to go on the road over Cranbury Head. But Mum ignored our feelings and put on her brave and merry manner which annoys Chris so much, and off we drove. Chris and I tried not to look at the pale new section of fence on the clifftop, and I think Mum tried too, but we could sort of see it even when we weren’t looking. There’s a big gap in the trees and bushes there, because it’s not quite spring yet and no leaves have hidden the place. Dad must have swooped right across the road from left to right. I wondered how he felt, in that last second or so, when he knew he was going over, but I didn’t say so. We were all pretending we hadn’t noticed the place.

Aunt Maria’s house failed to cheer us up. It’s quite old, in a street of other old houses, which look very picturesque, all in shades-of-cream-colour, and it’s not very big. It looks bigger inside – almost grand and imposing. It must be the big dark furniture. All the rooms seem dark, somehow, and it smells of the way your mouth tastes when you wake up to find you’ve got a cold. Mum hasn’t admitted to the smell, but she keeps saying she can’t understand why the house is so dark. “Perhaps if she put up cheerful curtains,” she says, “or moved the furniture round. The house must get quite a lot of sun through the garden at the back.”

Aunt Maria greeted us with the news that Lavinia’s mother was ill and Lavinia had gone to look after her. “It doesn’t matter,” she said, stumping towards us with two sticks. “Chris can have the little room now. I can manage quite well if somebody helps me wash and dress, and I’m sure you won’t mind doing the cooking, will you, Betty dear?”

Mum of course said she’d help in any way she could.

“Well, so you should,” Aunt Maria said. “You’re not at work at the moment, are you?”

I think even Mum privately found this a bit much, but she smiled and put it down to Aunt Maria being old. Mum keeps doing that. She points out that Aunt Maria was brought up in the days of servants and does not realise quite what she’s asking sometimes. Chris and I suspect that Aunt Maria no sooner knew we were coming than she gave Lavinia a holiday. Chris says Lavinia was probably going to give notice. He says anyone who has to live with Aunt Maria is bound to want to leave after an hour.

“We don’t need to have supper,” Aunt Maria said. “I just have a glass of milk and a piece of cheese.”

Mum saw our faces. “We can go out and find some fish and chips,” she said.

“What?! In Cranbury! ”said Aunt Maria, as if Mum had offered to go and carve up a missionary or the postman. Then she hummed and hawed and said if poor Betty was tired after the journey and didn’t want to cook, she thought there was a fish stall of some kind down on the sea front. “Though I expect it’ll be closed at this season,” she said.

Chris went off into the dusk to look, muttering things. He came back in half an hour looking windblown and told us that everything by the pier was shut. “And doesn’t look as if it had ever been open in the last hundred years,” he said. “Now what?”

“What a good boy you are to look after us all like this,” said Aunt Maria. “I think there were some nut cutlets Lavinia put somewhere.”

“I’m not a good boy, I’m hungry,” said Chris. “Where are the beastly nut cutlets?”

“Christian!” said Mum.

We went and searched the kitchen. There were two nut cutlets and some eggs and things, but there was only one saucepan and a very small frying pan and almost nothing else. Mum wondered how Lavinia managed. I thought she may have taken all the cooking things with her when she went. Anyway, we invented a sort of nut scrambled eggs on toast. When I set the table, Aunt Maria said, “We’re just camping out tonight. Don’t bother to put napkins, dear. It’s fun using kitchen cutlery.”

I thought she meant it, so I didn’t look for napkins until Mum whispered, “Don’t be silly, Mig! It’s just her polite way of saying she’s used to napkins and her best silver. Go and look.”

Mum was very good at understanding Aunt Maria’s polite way of saying things. It has already caused her a lot of work. If she doesn’t watch out, she’s not going to get any kind of holiday at all. It has caused her to clean the cutlery with silver polish and to roll up the hall carpet in case someone slips on it in the night, and put the potted plants in the bath, and force Chris to wind all seven clocks, and help Aunt Maria upstairs, where Mum and I undressed her and put her hair in pigtails, and plumped her pillows in the way Aunt Maria said she wouldn’t bother with as Lavinia was not there, and then to lay out her things for morning. Aunt Maria said we were not to, of course.

“And I won’t bother with breakfast, now Lavinia’s not here to bring it me in bed, dear,” was Aunt Maria’s final demand. Mum promised to bring her breakfast on a tray at eight-thirty sharp. It’s a very useful way of bullying people. I went downstairs and tried it on Chris.

“You don’t need to bother to bring the cases in from the car,” I told him. “We’re camping on the floor in our clothes.”

“Oh!” said Chris. “I forgot the damn cases …” And he had jumped up to fetch them before he realised I was laughing. He was just deciding whether to laugh or to snarl, when there was a hullabaloo from Aunt Maria upstairs. Mum, who was halfway down, went charging up in a panic, thinking she had fallen out of bed.

“When Lavinia’s here, I always get her to turn the gas and electricity off at ten o’clock sharp,” Aunt Maria shouted. “But you can leave it on since you’re my visitors.”

As a result of this, I am writing this by candlelight. Mum is on the other side of the candle, making a huge list of all the things we are going to buy for Aunt Maria tomorrow. Reading upside down I can see “saucepans” and “potatoes” and “fish slice” and “pruning shears”. Mum’s obviously been not-asked to do some gardening too.

We kept the electricity on until 10.15 in fact, so that we could see to get settled into our rooms. Chris’s little room is halfway up the stairs and full of books. I feel envious. I don’t mind sharing with Mum, of course, but the bed is not very big and the room is still full of Lavinia’s things. As Mum said, rather wryly, Lavinia obviously couldn’t wait to get away. Her cupboard and drawers are full of clothes. She has left silver-backed brushes on the dressing-table and slippers under the bed, and Mum has got all worried about not making a mess of her things. She has moved the silver brushes and the silver-framed photograph of Lavinia and her mother to a high shelf. Lavinia is one of those people who always look old. I remember thinking she was about ninety when I last came here when I was little. In the photo, Lavinia and her mother might be twins, two old ladies smiling away. One is labelled “Mother” and one “Me” so they can’t be twins.

Then at 10.15, when Mum was taking the potted plants out of the bath in order to make Chris get into it for what Chris calls washing and I call wallowing in his own mud, someone hammered at the back door. Chris opened it as Mum and I came running. A lady stood there beaming a great torch at us. She was Mum’s age – or maybe younger: you know how hard it is to tell – and she had a crisp, clean, nun-like look.

“You must be Betty Laker,” she said to Mum. “I’m Elaine. From next door,” she added, when she saw that meant nothing. And she marched past Chris and me without noticing us. “I brought this torch,” she explained, “because I thought you would have turned the electricity off by now. She insists on it. She worries about fires in the night.”

“Chris,” said Mum. “Find out where the switch is.”

“It’s behind the door here,” said Elaine. “Turn it off when I’ve gone. I’ll only stay a moment to make sure you know what needs doing. We’re all so glad you could come and look after her. Any problems up to now?”

“No,” said Mum, looking a bit dazed.

Elaine strolled past us into the dining-room where she sauntered here and there, swinging the big torch and looking at Mum’s knitting and my notebooks and Chris’s homework piled on various chairs. She was wearing a crisply belted black mac and she was very thin. I wondered if she was a policewoman. “She likes the place tidier than this,” Elaine said.

“We’re in the middle of unpacking,” Mum said humbly. Chris looked daggers. He hates Mum crawling to people.

Elaine gave Mum a smile. It put two matching creases on either side of her mouth, but it was not what I would call a real smile. Funny, because she was quite pretty really. “You’ve gathered that she needs dressing, undressing, washing and her cooking done,” she said. “The three of you can probably bath her, can’t you? Good. And when you want to take her for some air, I’ll bring the wheelchair round. It lives at my house because there’s more room. And do be careful she doesn’t fall over. I expect you’ll manage. We’ll all be dropping in to see how you’re getting on, anyway. So …” She looked round again. “I’ll love you and leave you,” she said. She shot Chris, for some reason, another of her strange smiles and marched off again, calling over her shoulder, “Don’t forget the electricity.”

“She gives her orders!” Chris said. “Mum, did you know what we were in for? If you didn’t we’ve been got on false pretences.”

“I know, but Aunt Maria does need help,” Mum said helplessly. “Where’s the electricity switch? And are there any candles?”

There were two candles. Mum added “candles” to her list before she got into bed just now. Now she’s sitting there saying, “These sheets aren’t very clean. I must wash them tomorrow. She’s not got a washing-machine but there must be a launderette somewhere in the place.” Then she went on to, “Mig, you’ve written reams. Stop and come to bed now or there won’t be any of that notebook left.” She was beginning on, “There won’t be any of that candle left either—” when Chris came storming in wearing just his pants.

He said, “I don’t know what this is. It was under my pillow.” He threw something stormily on the floor and went away again.

It is pink and frilly and called St Margaret. We think it is probably Lavinia’s nightdress. Mum has spent the last quarter of an hour marvelling about it. “She must have been called away in a hurry after all,” she said, preparing to have more agonies of guilt. “She’d already moved down to the little room to make room for us. Oh, I feel awful.”

“Mum,” I said, “if you can feel awful looking at someone’s old nightie, what are you going to feel if you happen to see Chris’s socks?” That made her laugh. She’s forgotten to feel guilty now and she’s threatening to blow out the candle.