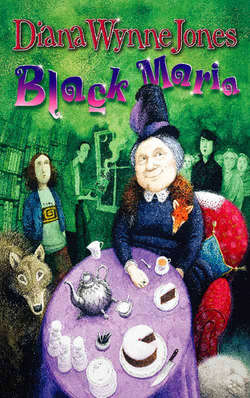

Читать книгу Black Maria - Diana Wynne Jones - Страница 8

CHAPTER TWO

ОглавлениеThere is a ghost in Chris’s room.

I wrote that two days ago. Since then events have moved so fast that snails are whizzing by, blurred with speed. I am paralysed with boredom, Mum has knitted three sleeves for one sweater for the same reason, and Chris is behaving worse and worse. So is Aunt Maria. We all hate Elaine and the other Mrs Urs.

How can Aunt Maria bear living in Cranbury with no television? The days have all gone the same way, starting with Mum leaping out of bed and waking me up in her hurry to get breakfast as soon as Aunt Maria begins thumping her stick on the floor. While I’m getting up, Aunt Maria is sounding off next door. “No, no, dear. It’s quite fun to eat runny egg for a change – I usually tell Lavinia to do them for five and a half minutes, but it doesn’t matter a bit.” That was the last two days. Today Mum must have got the egg right, because Aunt Maria was on about “how interesting to eat flabby toast, dear.” The noise wakes Chris up and he comes forth like the skeleton in the cupboard. Snarl, snarl!

Chris is not usually like this. The first morning, I asked him what was the matter and he said, “Oh nothing. There’s a ghost in my room.” The second morning he wouldn’t speak. Today I didn’t speak either.

Mum has just time to drink a cup of coffee before Aunt Maria is thumping her stick again, for us to get her up. We have to hook her into a corset-thing which is like shiny pink armour, and you should just see her knickers. Chris did. He said they would make good trousers for an Arabian dancing girl, provided the girl was six feet tall and highly respectable. I thought of Aunt Maria with a jewel in her tummy button and was nearly sick laughing. Aunt Maria made me worse by saying, “I have a great sense of humour, dears. Tell me the joke.” That was while Chris and I were helping her downstairs. She was in full regalia by then, in a tweed suit and two necklaces, and Mum was trying to make Aunt Maria’s bed the way Lavinia is supposed-to-do-it-but-it-doesn’t-matter-dear.

She comes and sits in state in the living-room then. It is somehow the darkest room in the house, though sun streams in from the brown garden. One of us has to sit there with her. We found that out the first day when we were all getting ready to go shopping for the things on Mum’s huge list. Chris was saying sarcastically that he couldn’t wait to see some of the hot spots in town, when Aunt Maria caught up with what we were talking about.

She said, in her special urgent scandalised way, “You’re not going out!”

“Yes,” said Chris. “We are on holiday, you know.”

Mum shut him up by saying, “Christian!” and explained about the shopping.

“But suppose I fall!” said Aunt Maria. “Suppose someone calls. How shall I answer the door?”

“You opened the door to us when we came,” I said.

Aunt Maria promptly went all gentle and martyred and said none of us knew what it was like to be old, and did we realise she sometimes never saw a soul for a whole month on end? “You go, dears. Get your fresh air,” she said.

Naturally Mum got guilty at that, and, just as naturally, it was me that had to stay behind. I spent the next three hundred hours sitting in a little brown chair facing Aunt Maria. She sits on a yellow brocade sofa with knobs on and silk ropes hooked around the knobs to stop the sofa’s arms falling down. Her feet are plonked on the wine-coloured carpet and her hands are plonked on her sticks. Aunt Maria is a heavy sort of lady. I keep thinking of her as huge and I keep being surprised to find that she is nothing like as tall as Chris, and not even as tall as Mum. I think she may only be as tall as me. But her character is enormous – right up to the ceiling.

She talks. It is all about her friends in Cranbury. “Corinne West and Adele Taylor told Zoë Green – Zoë Green has a brilliant mind, dear: she’s read every book in the library – and Zoë Green told Hester Bayley – Hester paints charming water colours, all real scenes, everyone says she’s as good as Van Gogh – and Hester said I was quite right to be hurt at what Miss Phelps had been saying. After all I’d done for Miss Phelps! I used to send Lavinia over to her, but I wonder if I should any more. We told Benita Wallins, and she said on no account. Selma Tidmarsh had told her all Miss Phelps had said. Selma and Phyllis – Phyllis Forbes, that is, not Phyllis West – wanted to go round and speak to Miss Phelps, but I said No, I shall turn the other cheek. So Phyllis West went to Ann Haversham and said …”

On and on. You end up feeling you are in a sort of bubble filled with that getting-a-cold smell, and inside that bubble is Cranbury and Aunt Maria, and that is the entire world. It is hard to remember there is any land outside Cranbury. I got into a kind of daze of boredom. It was humming in my ears. When you get that way, the most ordinary things get violently exciting. I know when I looked round and saw a cat on the living-room windowsill it was like Christmas or my birthday, or when Chris’s friend Andy notices me. Wonderful! And it was one of those grey fluffy cats with a flat silly face that are normally utterly boring. It was staring intensely in at us through the glass, opening its mouth and dribbling down its grey ruff, and I stared back into its flat yellow eyes – they were slightly crossed – as if that cat was my favourite friend in all the world.

“You’re not attending, dear,” said Aunt Maria, and she turned to see what I was staring it. Her face went red. She levered herself up on one stick and stumped towards the window, slashing the air with her other stick. “Get off! How dare you sit on my windowsill!” The cat glared in stupid horror and fled for its life. Aunt Maria sat back down, puffing. “He comes in my garden all the time,” she said. “After birds. As I was saying, Ann Haversham and Rosa Brisling were great friends until Miss Phelps said that. Now you mustn’t think I’m annoyed with Amaryllis Phelps, but I was hurt—”

I thought she was horrid to that cat. I couldn’t listen to her after that. I sat and wondered about Chris’s ghost. It could have been a joke. But if it wasn’t – I didn’t know whether I wanted it to be Dad’s ghost trying to tell Chris where his body was, or not. The idea made my teeth want to chatter, and I had a sort of ache of fear and excitement.

“Do attend, dear,” said Aunt Maria. “This is interesting.”

“I am,” I said. She had been talking about Elaine-next-door. I had sort of heard. “We met Elaine,” I said. “She came in last night with a torch.”

“You mustn’t call her Elaine, dear,” Aunt Maria said. “She’s Mrs Blackwell.”

“Why not?” I said. “She said Elaine.”

“That’s because I always call her that,” Aunt Maria said. “But if you do, it’s rude.”

So I’m calling her Elaine. Elaine came marching in again, in her black mac but without her torch, at the same time as Chris and Mum. I’d heard Chris’s voice and then Mum’s and I jumped up, feeling I was being let out of prison. Something was actually happening! Then the living-room door opened and it was Elaine. “Don’t go, dear,” Aunt Maria said to me. “I want you here to be introduced.”

I had to stand there, while Elaine took no notice of me as before. She went to Aunt Maria and kissed her cheek. “They’ve done your shopping,” she said, “and I told them where to put things. Is there anything else you want me to tell them?”

“They’re being very good,” Aunt Maria said. She had gone all merry. “They’re trying quite hard. I don’t expect them to get anything right straightaway.”

“I see,” said Elaine. “I’ll go and tell them to make an effort then.” She was not joking. She was like a Police Chief taking her orders from the Great Dictator.

“Before you do,” Aunt Maria said merrily, “I want you to meet my new little Naomi. Such a dear little great-niece!”

Elaine turned her face towards me. “Mig,” I said. “I prefer being called Mig.”

“Hello, Naomi,” said Elaine, and she strode out of the room again. When I went after her, I found her standing over Mum and Chris and scads of carrier bags, saying, “And you really must make sure she is never left alone.”

Mum, looking very flustered, said, “We left Mig here.”

“I know,” Elaine said grimly, meaning that was what she was complaining of. Then she turned to Chris. Her mouth made the stretch with two creases at the ends. “You,” she said. “You have the look of a gallant young man. I’m sure you’ll keep your aunt company in future, won’t you?”

We think it was meant to be flirtatious. We stared at one another as the back door shut crisply behind Elaine. “Well!” Mum said. “You seem to have made a hit, Chris! And talking of hits, hit her I shall if she gives me one more order. Who does she think she is?”

“Aunt Maria’s Chief of Police,” I said.

“Right!” said Mum.

Then we unpacked all the loads of provisions and, guess what? We found a deep-freeze in the cupboard beside the sink, absolutely stuffed with food. There was ice cream and bread and hot dog sausages and raspberries in it. Half the stuff Mum had bought was things that were there already. Chris sorted through it with great zeal. Mum is always amazed at how much he eats and keeps saying, “You can’t still be hungry!” I have tried to explain, from my own experience. It’s a sort of nagging need you have, even when you feel full. It’s not starving, just that you keep wanting more to eat.

“Yes,” says Mum. “That’s what I mean. How can you find room? Oh dear. We wronged poor Lavinia again. She left Aunt Maria very well supplied after all.”

Chris taxed Aunt Maria with this over lunch. Aunt Maria said loftily, “I never pry into the kitchen, dear. But frozen food is very bad for you.” And before Chris could point out that Aunt Maria was at the moment eating frozen peas, Aunt Maria rounded on Mum. “I was so ashamed, dear, when Elaine came in. The thought of her seeing you and Naomi in that state. And you went out like that, dear.”

“What state? Out like what?” we all said.

Aunt Maria lowered her eyes. “In trousers!” she whispered, hushed and horrified. Mum and I stared from Mum’s jeans to mine and then at one another. “And Naomi’s hair so untidy,” Aunt Maria continued. “She must have forgotten to plait it today. But of course you’ll both change this afternoon, won’t you? In case any of my friends call.”

“And what about me?” Chris asked sweetly. “Shall I wear a skirt too?” Aunt Maria pretended not to hear, so he added, “In case any of your friends call?”

“These peas are really delicious,” Aunt Maria said loudly to Mum. “I wouldn’t have thought peas were in season yet. Where did you find them?”

“They’re frozen,” Chris said, even louder, but she pretended not to hear that either.

It is very hard to know how deaf Aunt Maria is. Sometimes she seems like a post, like then, and sometimes she can sit in the living-room and hear what you whisper in the kitchen with both doors shut in between. Chris says the rule is she hears if you don’t want her to. Chris is thoroughly exasperated by that. He keeps trying to practise his guitar. In the little room halfway upstairs, with his door shut, Mum and I can hardly hear the guitar, but whenever Chris starts to play, Aunt Maria springs up, shrieking, “What’s that noise? There’s a burglar trying to break into the house!” I know how Chris feels, because Aunt Maria does that when I have my Walkman on too. Even if I turn it so low hardly a whisper comes into the earphones, Aunt Maria shrieks, “What’s that noise? Is the tank in the loft leaking?”

Mum has made us both stop. “It is her house, loves,” she said when we argued. “We’re only her guests.”

“On a working holiday!” Chris snarled. Mum was cleaning Aunt Maria’s brass, because Aunt Maria said that this was Lavinia’s day for doing it, but she didn’t-expect-Mum-to-do-it.

On the same grounds, Mum changed into her good dress and made me wear a skirt. I pointed out I’ve only got one skirt with me – my pleated one – and Mum said, “Mig, I’ll buy you another. We are her guests.”

“Oh good,” said Chris. “Is that a rule – visitors have to do what the owner of the house wants? Next time Andy comes round in London I’ll make him kiss Mig.”

That made me hit Chris and Aunt Maria shrieked that slates were falling off the roof.

“See what I mean?” said Chris. “It is her house. Pieces fall off if you hit me. Wicked, destructive Mig, knocking nice Auntie’s house down.”

I think he meant me to laugh, but Aunt Maria was getting me down too, so I didn’t. I stopped talking to Chris for a while. What with that, and being numbed with boredom, I didn’t manage to speak sensibly to Chris until two whole days later. It was silly. I kept wanting to ask him about his ghost, and I didn’t.

In the afternoons, Aunt Maria’s friends all come. They are the ones she talks about all morning. I had expected them all to be old hags, but they are quite ordinary ladies mostly in smart clothes and smart hairdos. Some of them are even nearly young, like Elaine. Corinne West and Adele Taylor, who came first, are Elaine-aged and smart. Benita Wallins, who came with them, was more the sort I’d expected, stumping along with bandages under her stockings, in a hat and a shiny quilted coat. From the greedy interested looks she gave us, you could see she knew we’d be there and couldn’t wait to inspect us. They are all Mrs Something and we are supposed to call them that. Chris calls them all Missis Ur and mixes their names up on purpose.

Anyway they came and Mum made them all mugs of coffee. Aunt Maria gave a merry laugh. “We’re camping out at the moment, Corinne dear. Now this is Betty and Chris, and I want you all to meet my niece, my dear little Naomi.” She always says that, and it makes me want to be rude like Chris, only I can never think of things to say until after they’ve gone. I am a failure and a hypocrite, because I feel just as rude as Chris. But it just doesn’t come out.

They must have gone straight next door when they left. Elaine marched in ten minutes later, using her two-line smile and uttering steely laughs. When Elaine laughs it is like the biggest of Aunt Maria’s clocks striking – a running-down whirr, followed by clanging. We think this means that Elaine is being social and diplomatic. She flings her hair back across the shoulders of her black mac and corners Mum.

“You’ll have a lot of hurt feelings,” she said, “if you give any of the others coffee in mugs.”

“Oh? What should I do then?” Mum asked, making an effort to stand up to Elaine.

“I advise you to find the silver teapot and her best china,” Elaine said. “And some cake if you’ve got it. You know how polite she is. She’d sit there dying of shame rather than tell you herself.” She shot out the two-line smile again. “Just a hint. I’ll let myself out,” she said, and went.

“Doesn’t she ever wear anything but that black mac?” Chris asked loudly as the back door clicked shut. “Perhaps she grows it, like skin.”

We all hoped Elaine had heard. But as usual she had conquered. Mum got out best tea things when Hester Bayley and three Mrs Urs turned up soon after that. Aunt Maria would not let me help because she wanted to introduce her “dear little Naomi” and when Chris tried to help, Aunt Maria said it was woman’s work. “I don’t trust him with my best china,” she added in a loud whisper to Phyllis Forbes and the other Mrs Urs. Mum ran about frantically and Chris seethed. I had to sit and listen to Hester Bayley, who was actually quite sensible and nice-seeming. We talked about pictures and painting and how horribly impossible it is to paint water.

“Particularly the sea,” Hester Bayley said. “That bit when the tide is coming up over the sand, all transparent, with lacy edges.”

I was saying how right she was, when Aunt Maria’s voice cut across everything. How can Elaine think Aunt Maria would rather die of shame than say anything?

“Oh dear! I do apologise,” Aunt Maria shouted. “This is bought cake.”

“Oh horrors!” Chris promptly said from the other side of the room. “Mum paid for it herself too, so we’re all eating pound notes.”

Poor Mum. She glared at Chris and then tried to apologise, but Selma Tidmarsh and the other Mrs Urs all began shouting that it tasted very wholesome, it was very good for a bought cake, while Aunt Maria pushed her plate aside and turned her head away from it. And Hester Bayley said to me, “Or a wave, with green shadows and foam on it,” just as if nothing had happened at all.

She gave me a book when she got up to go. “I brought it for you,” she said. “It’s the kind of pictures a little girl like you will love.”

“I’m sorry,” Mum said to Aunt Maria after they’d all left.

I think she was meaning she was sorry about Chris, but Aunt Maria said, “It’s all right, dear. I expect Lavinia has put the baking tins in an unexpected place. You’ll have found them by tomorrow.”

For a moment I thought Mum was going to explode. But she took a deep breath and went out into the rain and the wind to garden. I could see her savagely pruning roses, snip-chop, as if each twig was one of Aunt Maria’s fingers, while I put Hester Bayley’s book on the table and started to look at it.

Oh dear. I think Hester Bayley may be as dotty as Zoë Green underneath. Or she doesn’t know better. Mostly the pictures were of fairies, little flittery ones, or sweet-faced maidens in bonnets, but there were some that were so queer and peculiar that they did things to my stomach. There was a street of people who looked as if their faces had melted, and two at least of woodlands, where the trees seemed to have leering faces and nightmare, twiggy hands. And there was one called ‘A naughty little girl is punished’ that was worst of all. It was all dark except for the girl, so you couldn’t quite see what was doing it to her, but her bright clear figure was being pushed underground by something on top of her, and something else had her long hair and was pulling her under, and there were these black whippy things too. She looked terrified, and no wonder.

“Charming!” Chris said, dropping crumbs over my shoulder as he ate the last of the pound-note cake. “Mum’s being told off again, look.”

I looked out of the window into the dusk. Sure enough, Elaine was standing over Mum with her hands on the hips of her flapping black mac, and Mum was looking humble and flustered again. “Honestly—” I began.

But Aunt Maria was calling out, “What are you saying, dears? It’s rude to whisper. Is it that cat again? One of you call Betty in. It’s time she was cooking supper.”

This is the sort of reason I never got to speak to Chris, and never got to write in my notebook either. When I went to guide camp, it was more private than it is in Aunt Maria’s house. But I have made a Deep Religious Vow to write something every day now. I need to, to relieve my feelings.

The next day was the same, only that morning I went out with Mum and Chris obeyed Elaine’s orders and stayed with Aunt Maria. Would you believe this? I have still not seen the sea, except the day we came, when it was nearly dark and I was trying not to look at the piece of new fence on Cranbury Head. That morning we went round and round looking for cake tins, then up and down and out into the country behind, where it is farms and fields and woods, looking for the launderette. In the end Mum said she felt like a thief with loot and we had to bring the bundle of dirty sheets home again.

“Give them to me,” Elaine said sternly, meeting us on the pavement outside the house. She held out a black mackintosh arm. Mum clutched the laundry defensively to her, determined not to give Elaine anything. It was ridiculous. It was only dirty sheets after all.

Elaine made her two-line smile and even laughed, a whirr without the chimes! “I have a washing machine,” she said.

Mum handed over the bundle and smiled, and it was almost normal.

That afternoon Zoë Green turned up for best china and cake, and so did Phyllis Watsis and another Mrs Ur – Rosa, I think. Mum had made a cake. Aunt Maria had spent all lunch-time telling Mum it didn’t matter, to make sure Mum did, but she called out all the same while Zoë Green was kissing her, “Have you made a cake, dear?”

Chris said loudly from his corner, “She. Has. Made. A. Cake. Or do you want me to spell it?”

Everyone pretended not to hear, which was quite easy, because Zoë Green is quite cuckoo. She runs about and gushes in a poopling sort of voice – I can imitate it by holding my tongue between my teeth while I talk. “Stho dthis iths dhear dithul Ndaombi!” she pooples. “Ndow don’d dtell mbe. I dlovbe guessthing. You dwere bordn in lade DNovember. DYou’re Sthagitharius.”

“No, she’s not, she’s Libra,” said Chris. “I’m Leo.”

But no one was listening to Chris, because Zoë Green was going on and on about horoscopes and Sagittarius, loud and long – and spitting rather. She wears her hair in two buns, one on each ear, and long traily clothes with a patchwork jacket on top, all rather dirty. She’s the only one who looks mad. I tried several times to tell her I wasn’t born in November, but she was in an ecstasy of cusps and ruling planets and didn’t hear.

“Such a dear friend,” Aunt Maria said to me.

And Phyllis Ur leaned over and whispered, “We love her so much, dear. She’s never been the same since her son – well, we won’t talk about that. But she’s a very valued member of Cranbury society.”

They meant I was to shut up and let Z.G. go on. I looked at Chris and he looked back at me and then up at the ceiling. Bonkers, he meant. Then I sat there listening and wondering how it was I never seemed to talk to Chris at the moment, when I did so want to know if he really meant that about the ghost.

Then Mum brought in the cake. Chris looked Aunt Maria in the eye and got up to pass the cake round.

Aunt Maria said, in a sad low voice, “He’ll drop it.”

If that wasn’t the last straw to Chris, it was when Zoë Green dived forward and peered at the slice of cake he was trying to pass her. “What’s in this? Ndothing I’mb adlerdjig to, I hobe?”

“I wouldn’t know,” Chris said. “Those things in it that look like currants are really rabbit’s do’s, so if you’re allergic to rabbit’s do’s, don’t eat it.” Everyone, including Zoë Green, stared, and then began to try to pretend he hadn’t said it. But Chris seized a cup of tea and held that out too. “How about some horsepiss?” he said.

There was a gabble of people talking about something else, in the midst of which Mum said, “Christian, I’ll—” Unfortunately, I’d just taken a mouthful of tea. I choked, and had to go out into the kitchen to cough over the sink. Through my coughings, I heard Chris’s voice again. Very loud.

“That’s right. Pretend I didn’t say it! Or why not say, ‘He’s only an adolescent, and he’s upset because his father fell off Cranbury Head’? He did, you know. Squish.” Then I heard the door slam behind him.

Outcry. It was awful. Aunt Maria was having a screaming fit. Zoë Green was hooting like an owl. I could hear Mum crying. It was so awful I stayed in the kitchen. And it went on being so awful. I was coughing my way to the back door to get right away like Chris had, when it shot open and Elaine strode in, black mac and all.

“I’ll have to have a word with that brother of yours,” she said. “Where is he?”

All I can think of is that she has a radio link between her house and this one. How could she have known? I mean, she may have heard the noise, but how could she have known it was Chris?

I stared at her clean, stern face. She has awfully fanatical eyes, I couldn’t help noticing. “I don’t know,” I said. “Outside somewhere probably.”

“Then I’ll go and look for him,” Elaine said. She went out through the door and said over her shoulder, “If I can’t find him, tell him from me he’s riding for a fall. Really. It’s serious.”

I wish she hadn’t said ‘riding for a fall’. Not those words.

When the noise quietened down, I went back to the dining room. Both the Mrs Urs patted my arm and said, “There, there, dear.” They seemed to think it was Chris who upset me.