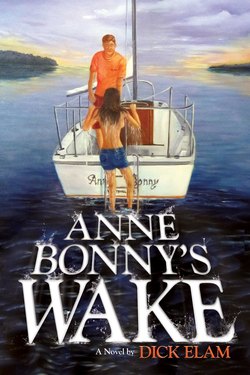

Читать книгу Anne Bonny's Wake - Dick Elam - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 6

Flutter. Flutter. Flutter.

The seagull flapped its wings and flew from the three marker poles called Gum Thicket Buoy. I knew I could reach Bill Havins’s radio from this distance. Went below and radioed my boat identification:

“Sloop Anne Bonny, WYP 457, calling Oriental Dockside.” Waited for an answer.

Tried again. “Anne Bonny calling Oriental Dockside.”

“Okay, Bon Ami. Oriental Backside here. Where are you, Hersh? Over.”

“Coming up north of Gum Thicket. Hey, Bill. How about you and Min having dinner tonight? Over.”

“That’s a big can do. Got you a berth at our dock. Over.”

“Thanks, buddy. And, Bill, how about a motel room for the night? Over.”

“Another can do. You getting soft, Bon Ami? A few days at sea and you gotta have a soft mattress. Jimmy will meet you at the dock with the key. Over.”

“See you in less than an hour. WYP 457 over and out.”

“Oriental Dockside, clear.”

I looked up through the hatch. Maggie Adelaide Moore continued to move her eyes across the Genoa jib sail, scan the mainsail, return her eyes to the Genoa up front, then back to look up the mast, eyes across the mainsail.

Maggie held the tiller with two fingers.

When I see a skipper squeeze a full fist over the tiller, I cringe. You can identify lubbers who grab the tiller as if they intend to row the boat. The good skippers adjust their sails, not the rudder, and reduce weather helm. Sails set correctly, the skipper holds course with a finger pull. Maggie Moore steered with that delicate touch.

I liked what I saw, but could I believe her story about the cockfight? Maybe. Maybe not. Professor Barstow, employ the interrogative technique you teach. Maybe make this encounter a case study for my criminal justice students come July.

I reviewed what she’d told me: Maggie had called Hilton Head “home.” That South Carolina resort suggested well-financed retirement. Maybe a two-hundred-thousand-dollar winter beach cottage near the golf course and the tennis courts, or membership in the yacht club. Maggie may have toned her well-cultivated body around the country club pool. She arched her legs as if she danced ballet. She referred to a family that practiced Protestant table manners. Maggie could be a well-mannered rich girl.

But she’d also sopped her eggs. She hitchhiked yachts. She cursed with shrewish disdain. She acted many roles.

Histrionics abounded. In one morning this woman had played many parts.

| Act 1: | Little Eva flees by swimming. |

| Act 2: | Simon Legree chases in a motorboat. Eva hides. |

| Act 3: | Virginia Woolf rails at her husband. |

| Act 4: | Alice, the efficient waitress, prepares breakfast. And tells about her family’s meal prayers. Also in the same act, she tells how she braves a redneck, employs subterfuge developed to outwit babysitters. |

| Act 5: | Horatio Hershel plays like a Captain Hornblower fool. Agrees to take beautiful woman for long sail. |

Despite my misgivings, I appreciated Maggie’s tiller skill. The wind continued strong, and the Anne Bonny boiled along the Neuse River.

Ahead, I counted about thirty sailboats. The Neuse Sailing Association raced this weekend. Half of the fleet had rounded Garbacon Beacon, put the wind to their stern, and sailed toward Oriental. With the wind behind them, those leaders had raised their balloon spinnakers, red and blue, blue and yellow, yellow and green and white, but no solid orange, like the distinctive Anne Bonny spinnaker.

I checked my watch. Almost noon. The Sunday morning race had been under way for two hours. Yearned to join the race. My Annie had understood my passion to race. She’d preferred to pleasantly cruise, but she’d accepted the challenge to race. I climbed into the cockpit. Checked the inclinometer. We were heeling only two degrees. Maggie saw me reading the heel indicator, and she must have read my mind.

“She handles beautifully,” Maggie said. “Good helm. But we could carry more sail, don’t you think, Skipper?”

I nodded agreement. Had Maggie read my mind? Besides a skilled touch on the tiller, maybe Maggie shared my compulsion to sail faster. Didn’t want to make my praise too effusive, but I felt compelled to compliment her. “You’re looking good on that tiller.”

She swept a hand across her spongy, mottled hair.

I meant her sailing ability. Forgot the paint and fiberglass in her hair. The breeze had blown away the acrid resin odor. I had even toned down my awareness of the shapely body in a tight T-shirt. Admired her sailing ability, not just her looks.

“You keep her sailing at a good clip,” I hastened. “But you’re luffing a little now.”

She corrected her tiller, took the wrinkle out of the sail, and increased her concentration. When the Anne Bonny returned to trim, she turned over the helm to me. She didn’t look me in the eye, just passed by as soon as I took the helm. Her cheeks wrinkled her eyes. I interpreted the look as Oops. Not looking good. If she thought that, she didn’t know how pretty she was on her bad hair day.

“While I’m in the hatch, may I get you something to drink or eat?” she asked.

“There’s cold beer in the icebox. Thank you. I’ll have one, won’t you?”

“Maybe a little later.”

She went below, handed me up a beer, and disappeared forward.

I decided to follow the racing boats around Garbacon Beacon to Oriental One marker, the finish line. Turned the tiller, eased the Genoa, and trimmed the mainsail. The Anne Bonny continued to lope. The knot meter pegged four and a quarter knots.

Maggie emerged from the head. She had wrapped a blue towel to make a turban. The towel hid her mottled hair. Her swept-up hair revealed a neck that arched with swan-like symmetry. She looked a foot taller and even more graceful. If she were my wife—and not mistaken for my younger sister—I would tell her to wear her hair on top of her head all the time. Except “behind closed doors,” as the song goes.

Maggie also brought up a second beer, opened her can, and relaxed against the cabin bulkhead. “May I ask a personal question?”

“Wait until we round Garbacon Beacon, and I get the spinnaker flying,” I answered and stowed my beer.

Gave Maggie the helm, while I rigged to raise the spinnaker.

I was rusty, so I made sure the halyard line would run free when I raised the spinnaker. Hooked up the spinnaker pole that would hold out her skirt, and let Anne Bonny again flaunt her bright, orange petticoat.

When you fly a spinnaker, you don’t want a bra-like tangle that sailors call a “Mae West.” And I didn’t intend to foul up this Sunday. I wrapped the sheet and guy around winches, cleated the guy that runs to the spinnaker pole, and handed the sheet to Maggie.

She held the spinnaker line ready in one hand, straddled the tiller, and with her other hand, she grabbed the mainsheet. We stood in the cockpit, ready to raise the orange chute when the wind blew on our backs.

Maggie maneuvered the boat around the marker with smooth pressure from her inner thighs.

Hand over hand, I pulled the halyard and raised the spinnaker. When the head of the orange sail reached mast top, I cleated. The spinnaker cloth began to flap. Furled the jib sail.

“Sheet!” I grunted.

She pulled in the spinnaker line on command. The orange parachute spread out on the leeward side of the Genoa sail.

I jumped back to the spinnaker guy, plunked a winch handle into the top of the winch, and cranked with one hand, while I pulled the guy with the other hand. The pole came aft, brought the orange spinnaker around the forestay for a healthy breath of Neuse River air. The spinnaker billowed to full size. The Anne Bonny heeled and surged downwind.

“Steer westerly. Course is 285 degrees. Ease your spinnaker sheet,” I commanded.

Maggie squeezed the tiller between her legs and let out the spinnaker sheet. I saw she strained against the pressure. I brushed past Maggie, grabbed the line, took another wrap on the winch, and cleated off the spinnaker sheet. She whooshed in relief, rubbed her hands, and grinned. I grinned back.

You refer to a sailboat in the female gender because she is cantankerous, capricious, demanding, expensive, and because a sailboat is beautiful. A flying spinnaker radiates optimum beauty, both from aboard and from ashore. Anne Bonny’s nylon spinnaker looked most womanly: The shoulders spread at the top. Then the spinnaker narrowed below the shoulders before filling out to graceful hips. Even the black skull sewed into the cloth looked feminine—thanks to the black rose between the teeth.

I eased the sheets, lifted the pole, and Anne Bonny picked up her orange skirt and danced to the freshening wind. The anemometer read sixteen knots of wind. The knot meter read five knots. The Anne Bonny sprinted near her maximum hull speed.

Ahead of her, three sailboats labored. Without spinnakers flying, the cruising boats sailed slower. Anne Bonny surged past them, smelled clear air, and charged for the anchored committee boat finish.

We sailed below the committee boat, waved. One of the race committee yelled a compliment for our good-looking spinnaker. Maggie Moore waved thanks before I could acknowledge.

Maggie smiled proudly as if we had just finished first. I considered planting a “good finish” kiss on her lips—the kiss Annie had said I always saved for a first-place finish, and forgot when we didn’t win.

When I realized the kiss I contemplated, I turned my back to Maggie Adelaide Moore, looked ahead to Oriental Harbor, and wondered: Who was this talented, soft-speaking, but strong-minded beauty? The second time in my life I had met a woman like her.